A collaborative publication of the Latin American Studies Program

Divisadero

Spring 2015

A Straight Line has Many Curves

The first thing you said when you were released from immigration detention in San Francisco was that you had no idea that the journey towards freedom would take over two years. As you sat in that Sansome St. fortress, all you remembered was fleeing violence to avoid capture by the warring tribes that were ripping apart your Ghanaian village. You were too worried about your wife’s safety to think about the elusive connections between Buku Accra and San Francisco or how Latin America serves as a geographical bridge between the two nations.

“They killed my father. After my father, they attacked me. I was working in the farm when they came there and attacked me and beat me up until I fell unconscious. So someone took me to the hospital. So, I was hospitalized for a week before I was discharged. So, I came back and I was just hiding in a different area just to make sure I'm OK before I take a next move. So I was there, like one month after they came again looking for me. They came, I was not around, so they met my wife and they hurt her, they beat her, they say she know where I am. She doesn't want to tell them, so they beat her and they left.”

You said the mounting pressure was too much for you to bear. Your thoughts were on escape. You knew Turkey could serve as a gateway to South America. First you would have to get to Nigeria from your border. Your mind raced. You thought back to how it all began.

“I was born in Ghana, Buku Accra, I grew up there, I was helping my dad in the farm, and I'm also, like, doing farming, I'm raising the animals: sheep . . . My tribe name is Monpursi. And also, my tribe, they are like, forcing us to fight the Kusasi tribe. So if you say you don't want to fight, it's like you turn your back against your tribe, so they might punish you as well. So to avert all those kinds of things . . . on July 18th, 2012 I left my country.”

You made your way to Lagos. From Lagos you flew to São Paulo, from São Paulo to Bogotá, from Bogotá to Ecuador. You spoke of many fears at that time; you thought of Ghana, you thought of your wife. You did not know that your main worry would soon be the dense jungles of Panama.

“Ecuador was my final destination. So I lived for like a couple of months then I came back to Colombia by bus. So Colombia we cross to Panama. We passed through the jungle for like, we spent like five days in the jungle. So from there to Panama. So Panama immigration detained us for like, two weeks there.”

Your words returned to the Panamanian jungle, always to the jungle. You were in a large party that included a fellow Ghanaian. You felt beholden to this man who did not speak Spanish at all; you were his only bridge of communication. You had met him in Panama, just before entering the jungle. You did not know he would run out of water and food before you and that you would have to share your rations without knowing if the jungle would ever end. At night, you slept under the trees. You could hear animals in the darkness. All around you: darkness. Insects crawled around you, snakes slithered through the trees. You could hear the rest of the group breathing, it was your only way to know they were there for the thick canopy blocked any hope of moonlight illuminating the undergrowth. Days into the jungle, when the group decided to walk more slowly to avoid exhaustion, you said it was a bad move. You convinced your friend to join you in continuing the journey, and for that reason you avoided arrest in the jungle. The remainder of the group was not so lucky. You and your Ghanaian friend made it to Costa Rica, and then Nicaragua.

“We were about to cross to enter Honduras but we were not lucky so they arrested us and they sent us back to Managua. They keep us there for a week . . . they did release us and the same day we crossed. We entered Honduras. We were going to Tegucigalpa. So we reached a checkpoint. There was a police on the roadside. He stopped the bus, and one of them entered inside the bus. So he took my friend but he didn't see me, so he left.”

You thought for a moment about continuing your long journey, but you knew you could not leave your friend who did not speak Spanish. You also knew you were a stranger in the country, and had no power to resolve any conflict that could arise. You were vulnerable in every way, and nearly out of money. Anything could have happened to your friend.

“I took myself to the immigration. I told them that I was with a guy, that they arrested him so I thought they would bring him here so that's why I hand myself over to you guys. So they say ‘no, they didn't bring him here.’ So, they keep me there almost like, 11 days. So, they also made a contact to see if they knew anything about him, but they couldn't get any information. So, they finally released me, they say I should go. So I left there to Guatemala, yeah. From Guatemala I came to Mexico. And in Mexico you walk, like two, almost, two days to Tenosique, Tabasco.”

The poverty stricken town of Tenosique is where you first encountered compassion. It was more compassion than you would find in the United States. Through your limited Spanish vocabulary, you found out about an immigrant house that was run by the church. You said the help you received there made you forget for a short time the distant country to the north.

“I told the father of that church that I want to seek asylum, he said OK, I will take you to the immigration on Monday, so prepare yourself. So Monday he took me to the immigration and I seek asylum there and they gave me, they approved my asylum and they gave me a greencard. I was living there for like 8 months, 8 and half months I lived in Mexico, in Tabasco, but things is a little bit hard for me, and by then the communication too is very difficult so I had been going around looking for a job, but, they don't offer me a job because they said I don't speak fluent Spanish. So, I decided to leave Mexico to the United States.”

You had saved a small amount of money, and the father gave you enough food to make the journey to Tijuana. You thought the asylum process in the United States would be as compassionate and simple as it was in Mexico. You expected them to listen to your story, to connect with your humanity, your tragedy. The journey from Tesonique to Tijuana lasted four days. You remembered arriving on August 19, 2013 and walking by foot to the border with San Ysidro. Soon, you would feel more lost within the US immigration detention system than you did in the jungle.

“So when I arrived there they checked my bag, they checked everything, they couldn't find nothing, so they took me to jail since then. So they first of all took me to California City, there was a way, I don't know if it's in the north, south right? Yeah, they took me to that place. I stayed there for, two months, yeah, two months ten days, and then they moved me to Sacramento. I stayed in Sacramento one week. On November 5th they moved me to CoCo county [Richmond, CA]. Yeah, I don't know why they transferred, I don't know, they didn't even tell us anything about it. When they, I just got transferred they didn't say nothing.”

You said that not knowing what was happening was one of the worst parts of your treatment in US immigration custody. You remembered how you were treated better in Panama, in Mexico, in Nicaragua, in every country that, like yours in Africa, had been victimized by the giant to the north. Now you were in their clutches. You had no way to contact Africa and check on your wife, on your family, on your tribe. The jail phone could not make international calls. No one knew you were there, no one knew you were anywhere. No one knew you. It was over a year you would sit in US immigration detention.

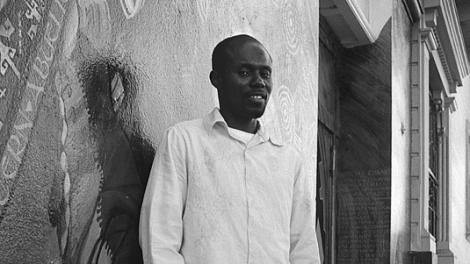

Author’s note: I first came across Mr. Tony Billa at the West County Detention Facility through my work with Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement (CIVIC). I run a local weekly visitation program, and when our team identified Mr. Billa and his situation, we stayed in close contact with him and advocated for his release. He is now out of detention and living with one of our volunteers, but is still fighting his case for asylum. His story is unfortunately not unique. Often lost in the mainstream narrative of Latino immigrants are the varied continental & transnational stories of migration, often by West African migrants.

The device of juxtaposing quotations with second-person narratives is in respectful homage to the recently departed feminist writer and documentarian, Helen Gary Bishop, who utilized this technique in 1984 when writing the obituary for one of my photographic heroes, Garry Winogrand. Mr. Winogrand is in large part the impetus and compass for my photographic work. My portrait of Mr. Billa was shot with a 28mm lens and Tri-X film pushed to 1200iso, also in homage to Mr. Winogrand.