A collaborative publication of the Latin American Studies Program

Divisadero

Spring 2015

Herida Abierta, Healing Herstory: Mi Testimonio Transfronteriza

“There is great good in returning to a landscape that has had extraordinary meaning in one’s life. It happens that we return to such places in our minds irresistibly. There are certain villages and towns, mountains and plains that, having seen them walked in them lived in them even for one day, we keep forever in mind’s eye. They become indispensable to our well-being; they define us, and we say, I am who I am because I have been there, or there.”

N. Scott Momaday, “Revisiting Sacred Ground,” in The Man Made of Words

Mi madre se escapo de su casa en México después de conocer a mi papa cuando tenia 14 anos. Ella había sido criada en los Estados Unidos, y recién llevada a vivir a México. Pero solo fue de mal, en peor. Se fue con mi papa para no estar entre los pleitos de mis abuelos, ya que mi abuelo solo quería regresar a mi abuela, mi mama, y mi tía para México para estar con otras mujeres. Después naci yo, y cuando mi mama realmente ya no soportaba que estaramos alla, me trajo a vivir a los Estados Unidos--pero yo nunca me fui de México.

What generation are you? Were you born here? Are you an immigrant? YOU DON’T LOOK MEXICAN. Generations, nationalities, and histories are as fluid as the borders and categorized identities that are meant to divide us. Just as futile. There was never a point where all of my family, or even one side of my family, decided to pick one country over the other, and sure, I wasn’t born in Mexico, but I did spend a great part of my life there, so where does that leave me?

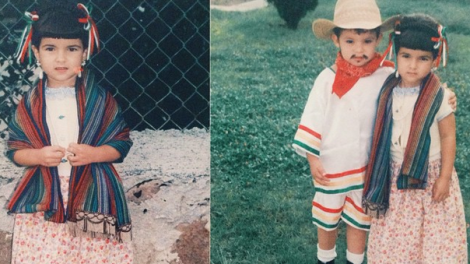

Uno de mis últimos recuerdos de Mexico es en el Kinder, coloreando a La Nina, La Pinta, y La Santa Maria, literally the vehicles of the colonization of the Americas. Después de migrar, pase todos mis veranos allá, en el balneario de mi abuelo materno, en el rancho que era de su abuelo, entre los mezquites, con sus aguas termales que brotaban de una tierra que sentíamos en la sangre. Mi abuelo, quien era hijo de un bracero, es el que mas me conecto con el campo y con el valor del trabajo, mientras que my paternal grandma would sit me down for hours to read me the speeches that she gave as mayor, to show me the death threats that the narcos would send to her when she would call the federales, to talk to me about her thesis. De ambos lados de mi familia veía personas exitosas y respetadas, pero por el lado de mi papa era por privilegio, y por el lado de mi mama era por el jale constante de mi abuelo. Pasando el verano regresaba a este lado a ver a una gente con quien me sentía tan conectada vivir de una forma tan diferente, y fue cuando se me ocurrió que el vivir entre fronteras, cambia nuestra percepción de la realidad. No es decir que todo es perfecto allá, pero me doy cuenta de que son realidades dependientes y compartidas.

Me crie con un gran dolor, que se hizo un gran coraje. “Are you White? You don’t look Mexican.” Alomejor nomas no reflejo la imagen que te permite abusar de nosotros y vivir complaciente con la injusticia. Otra parte del dolor era no entender bien mi propia historia, lo que había pasado con mis padres, porque estábamos acá, sola con mi mama viviendo como una estadística Latina de madre joven soltera. Me crie entre mujeres y libros. The recounting of my memories does not have a place in a masculinist, “objective” history, pero lo individual no es solo personal. Omitting the personal, or the “subjective” justifies power, and keeps power from having to explain the way it would like for our realities to be imagined.

In her book, ¡Chicana Power!: Contested Histories of Feminism in the Chicano Movement, Maylei Blackwell introduces “retrofitted memory” to understand cultural roots, histories of resistance, and to create/critique the representations of one’s own, essentially complicating liminal social spaces, in order to criticize from within, and to survive. I saw that my story is retrofitted memory, it is one of colonial Mexico, of braceros, of narcos, of borderlands, of a niña that could not speak a word of English her first day of Kindergarten but was always being distanced from her raza because of her skin color, class, or ethnicity. This memory is not revisionist history that speaks for a people that are assumed to be silenced, but to show the power of testimonio, of oral history more generally, and of telling one’s story to empower us, both by individualizing and contextualizing, to show us that our stories have the power to shape realities. My story transcends citizenship, or nations, because it is between nations, it is a mapping of my own trajectory and definitions of space, and it is amongst the memories and voices of women. Retrofitted memory is a way to illustrate just how fluid this seemingly compartmentalized sequence of memories and movements is.

We know what it is like to be a child in search of a book that has an apellido on it that sounds familiar, and now, as a young Xicana, I know what it looks like to tell one’s story and to speak against the absence of representative histories. Going from memories, the way that the crossing has continually informed my life, and from women and books, I am constantly informing my present realities with my experiences. Por ejemplo, soy parte de Mujeres Unidas y Activas (MUA), a grassroots non-profit organization for Latina immigrants with a double mission of personal transformation and community empowerment for social and economic justice. He podido transformar el coraje y la indignidad en comunidad con mujeres que comparten mis preocupaciones y a un nivel, mis experiencias. Estoy donde comencé, entre mujeres y entre libros. Sigo siendo la baby, la que ven como muy madura para su edad. By telling this story, I am shaping my reality.

I guess that my silencing as a child crossing borderlands only led to greater cultural pride and dissidence. Venimos de nuestros países de todos los colores y sabores, y no hay una experiencia migrante Latina, pero el saber y el grito que nos sale de un lugar tan profundo, resulta en el mismo poder para mi, para mi compañera trabajadora del hogar Centro Americana, para mi profesora, para todas nosotras que damos la voz. Nuestras realidades son basadas en las historias que nos dicen de nosotras, de las historias que nosotras nos decimos a nosotras mismas, de las historias que buscamos, de las historias que aplicamos a nuestras vidas, porque en cuanto uno escucha una historia, o cuenta su historia, se queda con nosotros. Es nuestro deber complicar las categorías que nos determinan.

Como mencione, cuento mi historia lo mejor que puedo, y es algo que solo seguirá cambiando cuando mi futuro llegue y cuando las cosas del pasado sean mas claras. Lo que quiero decir es que no necesita ser claro todo, I only need to continue to create my own space informed by my movement across space. Y seguir encontrando fortaleza en el ejemplo de las mujeres de mi vida que me no se han quedado ni en un lugar, ni calladas, ni satisfechas con lo que el sistema del heteropatriarcado capitalista nos quiere dar.