Otoño / Fall 2018

Change the World from Here: Representation and Mental Health Access at USF

I consider myself a “woke” white girl who also must regularly address her own privileges. Some are easier to address than others, such as having access to mental health services that are sensitive to my particular background. Recently, the story of the hiring of a new black psychologist, Dr. Dominique Broussard to Counseling and Psychological Services led me to the realization that, as a white woman, I could easily find psychological services with someone who shared my background. This is not the reality for a lot of students of color, queer or DACA identified students on campus. While USF is renowned for its diversity, inclusion, and for its passion for social justice, without emboldened students USF would not be the diverse educational institution it is today. And to say that does not take away from the growth USF still needs to accomplish in this area.

When Realization Began to Strike

In 2014, the Black Student Union crafted a list of demands for the University of San Francisco, which included the request to hire a black psychologist on staff to CAPS. Their demands were part of a national trend to push universities and institutions who had failed to meet the needs of their diverse student populations. While Dr. Broussard is not the sole person of color in the CAPS office, her hiring marked a win for BSU students and faculty who had demanded more diverse representation around campus. This makes sense given the fact that the last black psychologist hired at CAPS was Dr. Phil Coleman in the 90’s. It also led to questions about how key programs such as CAPS reflect the student population and if it does so proportionately to support its students of color. So I chose to explore CAPS and its diversity amongst its counselors and psychologists in relation to the diversity of the USF student population.

My initial interviews taught me that the topic of diversity and staffing choices in higher education is much more complicated and multi-faceted than I thought. One of USF’s core values is that we act as “people for others.” Can USF faculty and staff support its growing diverse student population and be “men and women” for its students if they don’t mirror its student population? Dr. Wardell-Ghirarduzzi, Vice Provost for Anti-Racism, Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (ADEI), recognizes that USF has a long way to go to have its faculty and staff mirror the student population, but she shares that USF, along with universities across the nation, really doesn’t have a choice. As schools become more diverse, institutions need to become more intentional in their hiring practices and in how they support their students of color. In other words, the choice no longer exists to be complacent and not place inclusion and diversity as a top priority for universities across the nation.

The Demand for CAPS

CAPS started some 50 years ago and was originally called the Counseling Center. While the exact creation is unknown, many similar centers across the country began after WWII to service vets and help them in their transition into higher education. It had a developmental focus rather than a medical one. Since then, CAPS has transformed at the university and has taken on many roles.

When I began delving into understanding the role of diversity at CAPS I had the pleasure to sit down with Senior Director of CAPS, Dr. Barbara Thomas. I wanted to know how the demand for counseling and psychological services has grown and whether the university has been able to respond to the growing number of students of color on campus that request them. Upon commenting on the growing demand for services, Dr. Thomas jokingly replied, “bring back stigma,” because CAPS can’t keep up with the demand. Stigma is defined as “a mark of shame or discredit (Merriam-Webster)” and while Dr. Thomas acknowledged that stigma still does exist, especially among our 15.5% international students and our students of color, overall stigma has decreased, especially within my generation between people of the ages 18-23 which constitutes a majority of CAPS clientele. This echoed the need for psychologists and counselors of color for non-white students, a population that still deals with on average higher amounts of cultural and social stigma regarding mental health.

In her past role as Dean of Students, Dr. Wardell-Ghirarduzzi oversaw CAPS, so she understands the importance of crafting mindful spaces for all of USF’s students. She stated that “when students come on campus and they are not part of the dominant culture, they experience things others do not feel,” their “unique experiences” of being a minority in a new space, coupled with the adjustment of being away from home create new difficulties that “non-black [non person of color] clinicians and psychologists may not be able to truly understand.” Further emphasizing the need for diversity amongst CAPS psychologists.

Dr. Thomas sips her tea and states, “the only way... that we will have additional staffing in CAPS is if the students say its a priority.” But, why must it be on students to demand change, representation, or resources that they deserve when they pay upwards of $42,000? If USF wants its faculty and staff to be “people for” its student population, why isn’t USF practicing what it preaches? But, according to Dr. Thomas, the situation is far more complex due to the difficult recruitment process at CAPS and the sad reality that USF CAPS psychologists get paid on average $10,000-$15,000 less than their counterparts at UCs and other public institutions, adding to economic pressure of living in one of the nations most expensive cities. This helped me understand the barriers to real change, but it also showed the impact possible when students are able to demand change and representation. Considering the difficulties faced by this very crucial program, I was also reminded that the priority is the students, so CAPS, along with the university need to make things work for its student population regardless of those logistical and practical difficulties.

Dr. Thomas expanded about the diversity that CAPS does have; its four individuals who identify as people of color, along with people who identify along the LGBTQ+ spectrum, and those who speak languages other than English. She also highlighted the contributions black trainees have made over the years. But the question still rang, is it enough?

Dr. Thomas began to share information on CAPS intercultural focus. Its various seminars cover “sexual fluidity, undocumented students, African American students, and social class” amongst many others, that are led by clinicians and attended by staff with the goal to help them understand how to support students of various identities. She shared that CAPS is known for this cultural competency and training in that area. But can intercultural competence make up for lacks in diversity? I did some more digging…

Asian: 2,238 (20.9%)

Asian: 2,238 (20.9%)

African American: 582 (5.4%)

Latino: 2,252 (21.0%)

Native American: 19 (0.2%)

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander: 74 (0.7%)

Multi Race: 748 (7.0%)

International: 1,496 (14.0%)

Unknown: 315 (2.9%)

White: 2,990 (27.9%)

TOTAL: 10,714

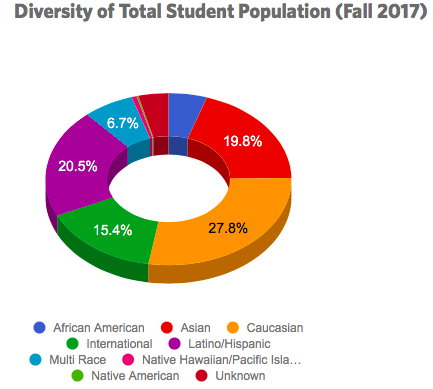

According to Fall 2017 data USF's student population is 5.1% Black, 20.6% Latinx, 19.9% Asian, amongst many other identities. Based on the same Fall 2017 report, that 5.1% black population makes up 570 students, yet only 67 black students walked into CAPS and received help. At the beginning of my interview, Dr. Thomas mentioned that CAPS psychologists could be doubled, yet they would still face difficulties accommodating students, especially students who request a specific identifying counselor. In fact, there is a growing number of female students of color who request Dr. Broussard. If she is not available, they tend to request any other available woman of color psychologist. This proves that students do want psychological support from those who share a similar background, and/or may have a better understanding of their identity, as Dr. Wardell-Ghirarduzzi explained. The logic follows that if CAPS did have more psychologists of color, more students of color could receive more support.

| Race | Total Clients | CAPS% | USF% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asian American/Asian | 197 | 21.1% | 22.84% |

| African American/Black | 67 | 7.2% | 6.34% |

| White | 296 | 31.7% | 28.06% |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 174 | 18.6% | 20.93% |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 15 | 1.6% | 1.72% |

| Arab American/Middle Eastern | 22 | 2.4% | N/A |

| Multiracial | 106 | 11.3% | N/A |

| Other | 21 | 2.2% | N/A |

| Prefer not to answer/No Response | 16 | 1.7% | 3.52% |

I then grew interested in other student populations on campus that needed support, this brought me to our undocumented student population.

Change on Campus

Dr. Al Meza, a psychologist on staff at CAPS and member of the University’s DACA Task Force described the “multiple stressors” that our schools undocumented population endure that differ immensely from your “average USF student.” He explained that these stressors need to be addressed and that the DACA Task Force can help.

The DACA Task Force was created 3-4 years ago by our then President Steve Privett with the goal to support our growing undocumented population. One of the things that the task force does is offer an undocumented student allies educational workshop with the goal to educate USF faculty and staff on how to support the undocumented community at USF. CAPS psychologists also take part in this training with the goal to build a collective community for its undocumented students. The uncertainty of the life of an undocumented student highlights the urgency of having more psychologists and counselors that share a background or training in different communities of color that include a variety of identities. However, it’s not enough to just increase the number of health professionals from different backgrounds. A study of the Rand Health Quarterly found that Latinx adults “are the least likely to have used mental health services of all the racial/ethnic groups included in the study.” So while stigma is decreasing it also is still prevalent in communities of color, specifically those identified as Latinx. While I love the idea of having more psychologists of color available I also realize that social and cultural change needs to occur so that people don’t associate shame with seeking mental health support.

Looking Ahead

So how does change come about at USF? How can we support the growth of these programs and initiatives? And how can we alter cultural stigma around mental health issues and treatment? After hearing Dr. Wardell-Ghirarduzzi’s answer I felt hopeful. She shared that “change happens from those who are impacted the most by inequity,” and this happens when they start to understand that they aren’t alone in their marginalization. And while change is happening, she acknowledges that “it is slow moving, nonetheless a firestorm is starting to build.” I wanted to know how students could support ADEI initiatives and her answer was quite simple, she said that students need to unite with like minded individuals, start clubs and organizations with social justice aims and initiatives, in other words, “you gotta find your people.”

It was a touching way to end our conversation. That the solution to problems of inclusivity and diversity could be remedied by an increase in community and togetherness; that students do have a voice and should feel empowered to use it; that I have a voice, a privileged one for that matter and I have an obligation to use it. BSU’s demands made an impact. Students therefore can make an impact; we just need to be willing to fight for what we believe in and organize ourselves. I was so excited to learn about the change and impact that BSU had accomplished that I forgot to challenge myself to take part in the change itself. This story started when I heard about the hiring of a new black psychologist on staff at CAPS and through my various interviews it became so much more. First off, it taught me journalism is hard, second, that the university is interested in having these conversations, and lastly that I will always have to be checking my own privileges and leveraging those I do have to make a difference. I can call myself as woke as I want, but if I’m not taking a part in the action and the fight necessary for change, I am failing. Time to ask yourself if you are too.