Iconographies of Urban Masculinity: Reading “Flex Boards” in an Indian City

REFERENCES | AUTHOR BIO | ![]() Download the PDF |

Download the PDF | ![]() Download the Accessible PDF

Download the Accessible PDF

Keywords: Masculinity, India, advertising, flex boards

Introduction

On an unusually warm evening in early May of 2012 I rode my scooter along the congested lanes of Moti Peth1 on my way to “Shelar galli,2” a working-class neighborhood in the western Indian city of Pune, where I had been conducting my doctoral field research for the preceding fifteen months. As I parked my scooter at one end of the small stretch of road that formed the axis of the neighborhood, it was impossible to miss a thirty-foot-tall billboard looming above the narrow lane at its other end. I was, by now, familiar with the presence of “flex” boards, as they were popularly known, as these boards crowded the city’s visual and material landscape. However, the flex board in Shelar galli that evening was striking, given its sheer size and the way in which it seemed to dwarf the neighborhood with its height (see figure 1.1).

The image of Mohanlal Shitole, a resident of Shelar galli, dressed in a bright red turban and a starched white shirt, with a thick gold bracelet resting on his wrist, stood along the entire length of the flex making it seem like he was towering above the narrow lane itself. The rest of the space was dotted with faces of a host of local politicians (all men, barring one woman councilor) and (male) residents of the neighborhood, on whose behalf collective birthday greetings for Mohanlal were printed on top of the flex. Having been witness to Mohanlal’s strong ambition to make a foray into local politics by this time, I was hardly surprised by the fact that this flex was sponsored by and erected by Mohanlal himself, on the eve of a grand celebration of his birthday in the neighborhood. Mohanlal cut his birthday cake (after proudly brandishing a sword) to ear-deafening music, in full presence of the residents of the neighborhood. Following this, young and older male residents of the neighborhood lined up to greet Mohanlal and hand him bouquets of flowers, while making sure that they took a picture with him. As the rush of guests continued to swell, Mohanlal’s huge flex swayed in the breeze, overseeing as if with studied approval the success of his birthday celebration (see Figure 1.2).

The image of Mohanlal Shitole, a resident of Shelar galli, dressed in a bright red turban and a starched white shirt, with a thick gold bracelet resting on his wrist, stood along the entire length of the flex making it seem like he was towering above the narrow lane itself. The rest of the space was dotted with faces of a host of local politicians (all men, barring one woman councilor) and (male) residents of the neighborhood, on whose behalf collective birthday greetings for Mohanlal were printed on top of the flex. Having been witness to Mohanlal’s strong ambition to make a foray into local politics by this time, I was hardly surprised by the fact that this flex was sponsored by and erected by Mohanlal himself, on the eve of a grand celebration of his birthday in the neighborhood. Mohanlal cut his birthday cake (after proudly brandishing a sword) to ear-deafening music, in full presence of the residents of the neighborhood. Following this, young and older male residents of the neighborhood lined up to greet Mohanlal and hand him bouquets of flowers, while making sure that they took a picture with him. As the rush of guests continued to swell, Mohanlal’s huge flex swayed in the breeze, overseeing as if with studied approval the success of his birthday celebration (see Figure 1.2).

As I consolidated my doctoral research around the ways in which urban space and gendered identities were articulated – specifically in the context of young, working-class, Dalit3 men in Pune – the flex boards seemed to be located precisely on this point of articulation: as a distinctly urban and a gendered popular practice. While my ethnography remained firmly focused on the young men’s lives in Shelar galli, I continued in subsequent years to document flex boards as a crucial, publicly-displayed index of how this constituency of young men in the city imagined “being a man.”

This paper is based upon my extensive documentation of flex boards between the years 2014 - 2016 in the city of Pune. I turn an analytical lens on the practice of erecting flex boards in the city to illustrate how these boards serve as a site for young, subaltern men to imagine and perform a gendered self. This practice has crucial implications for the increasing class- and caste-based disparity situated in contemporary Indian cities. In this paper I demonstrate that the practice of erecting flex boards also signifies an attempt by the city’s subaltern (men) to (re)write themselves into the city’s public spaces and the city’s public life, thus challenging their gradual marginalization from the former. The landscape of flex boards, I argue, makes available to us a peculiar iconography of contemporary urban masculinity, constituted by an alignment of class-specific motifs of manliness, consumption and politics in urban India.

In the following section, I locate this paper in the context of two broad frames: firstly, the increasing attention paid to the hitherto neglected questions of masculinity, in the context of gendered relations in India; and secondly, the discourse around cities in contemporary India and the place of masculinity in this discourse. The second section of the paper presents ethnographic data in order to illustrate flex boards as a site of performance of subaltern urban masculinity.

Frames of Reference: Meanings and experience of masculinity in South Asia

A critical focus in the social sciences on studying men as “men” is relatively recent in India (and in the larger context of South Asia), gathering momentum only in the last two decades. Early research was based in history, in the discipline’s investigation of the discursive deployment of notions of masculinity (and femininity) which inscribed colonial and post-colonial India with unmistakably gendered meanings. Sinha’s landmark study has shown how the figures of the “manly Englishman” and the “effeminate Bengali babu”4 that emerged in nineteenth-century colonial India encoded within them the constant power dynamics between the colonizers and the colonized, rooted in political, economic and administrative imperatives of the imperial rule.5 In its twentieth-century response to this Orientalist internalization of themselves as effete, the Indian elite sought to wrest back their power by advocating cultural nationalism. They reinvigorated a Hindu masculinity that blended qualities like discipline, loyalty, and courage blended with an emphasis on character-building, education and selfless service to the nation to consolidate the masculine ideal of a “real Hindu man.”6 Srivastava presents a fascinating analysis of the post-Independence project of producing the modern Indian citizen as a gendered project, to be achieved via “Five Year Plan Hero;”7 this figure was epitomized in Hindi cinema’s male protagonists of the 1950s and 1960s as engineers, doctors and scientists, who embodied the rational, scientific masculinity of modern India and mastered its incipiently urban spaces.8

The above research while elaborating upon the discursive content of masculinity in modern India, proves to be inadequate to illustrate the everyday experiences and notions of being a man in present day India. The 2000s however, have seen a burgeoning of work which investigates a range of sites where masculinity is produced and performed, including work,9 modernity and consumption;10 queerness and practices of sexuality,11 migration,12 communal violence,13 local politics;14 and all-male sites like wrestling,15 movie-going16 and neighborhood clubs.17 This research elaborates upon the processes of making and unmaking of masculine identities which are embedded in constellations of gendered, class, caste or ethnic relations. Going beyond simplistic renderings of masculinity in terms of patriarchal dominance or hegemonic masculinity, the above body of literature underlines the vulnerabilities which disrupt the links between maleness and power and the consequent recuperative strategies of the actors. It is within this larger frame that I situate this paper, as I analyze how contemporary representations of manliness in urban India are informed by the vulnerabilities that cities continue to produce for their working-class male citizens and simultaneously the avenues that representations provide for these men to reclaim a sense of masculine control.

Cities in India and their men

In the more than two decades since India liberalized its economy in 1991, Indian cities (big and small) have undergone fundamental spatial and social reconfiguration which is pegged onto class, gender and caste differences. A major highlight of this transformation has been the recasting of the notion of “public” in the exclusive image of the urban, middle-class consumer-citizen in globalizing India.18 This revised image is manifested in the realm of the public in its spatial and social manifestation. Thus contests over existing urban spaces have sharpened acutely19 as public space has become increasingly privatized via the mushrooming of exclusive consumer spaces, malls, multiplexes and gated communities.20 A new brand of middle-class civic activism is asserting its presence in the governance and management of urban public life, edging out the imagination of an inclusive city via its subscription to neoliberal notions of efficiency, “world-class”- ness and most recently “smart cities,”21 which views the presence of urban poor as nuisances22 or as hostile bodies.23

In the more than two decades since India liberalized its economy in 1991, Indian cities (big and small) have undergone fundamental spatial and social reconfiguration which is pegged onto class, gender and caste differences. A major highlight of this transformation has been the recasting of the notion of “public” in the exclusive image of the urban, middle-class consumer-citizen in globalizing India.18 This revised image is manifested in the realm of the public in its spatial and social manifestation. Thus contests over existing urban spaces have sharpened acutely19 as public space has become increasingly privatized via the mushrooming of exclusive consumer spaces, malls, multiplexes and gated communities.20 A new brand of middle-class civic activism is asserting its presence in the governance and management of urban public life, edging out the imagination of an inclusive city via its subscription to neoliberal notions of efficiency, “world-class”- ness and most recently “smart cities,”21 which views the presence of urban poor as nuisances22 or as hostile bodies.23

The furious debate on women’s safety which was triggered by the brutal rape and murder of a young paramedical student in Delhi in December of 2012,24 has to be located in the larger context of neoliberal urban India elaborated above. The outrage expressed in large-scale public demonstrations in the capital city and in national print and social media following the incident made way for larger discussions surrounding linkages of power, violence and masculinity and the institutionally entrenched misogyny in Indian public life. However, with the media giving disproportionate coverage to instances of lower-class men’s attacks on middle/upper-class women, the discussion around women’s safety was subtly framed as middle-class women’s increasing vulnerability to the violence of lower-class masculinity.25 It is important to note here that lower-caste referent is often implied in allusions to lower-class/working-class in debates/ discussions in the popular sphere. The prevalent intersection of class marginalization with caste-based disempowerment in the Indian context means that constructed fears of violent lower-class masculinity also thinly disguise similar reservations about lower-caste masculinity. Thus although the increased discussion of notions of manhood in the public sphere was welcome, the terms of the discussion were questionable.

Phadke traces the progressive consolidation of the image of working-class men as violent “lost causes”26 and as obstacles to progress in the development discourses of 1970s to their contemporary portrayal as dangerous, “unfriendly bodies”27 in discussions of urban women’s safety. In the distinctly neoliberal ethos of contemporary urban India, Phadke argues that, “Women’s safety, or to be more specific, middle and upper-class women’s safety, is… premised on the removal of lower-class and minority men from public spaces.”28 The above developments point towards the contradictory ways in which masculinity has come to occupy space in public discussions on urban India: while the sensitivity towards the gendered nature of urban spaces and the need to look at dominant meanings of masculinity is no doubt welcome, these discussions seem to highlight a disturbing alignment of class, masculinity and violence as a singular concern within the larger realm of masculine identity, pitting the former against middle-class women’s respectability. These shifts have molded the popular discourse on masculinity in urban life in contemporary India in a profoundly uneven manner: the figure of the working-class/ lower caste/ migrant man has been rendered as dangerous and undesirable as opposed to the unprecedented celebration of the suave, upper-caste, professional and English-speaking image into which the “urban man” is increasingly being cast.

The celebration of the middle-class male figure in popular discourse is made obvious in a spate of advertisements29 in recent years which address upper-caste, middle-class men explicitly, emphasizing their duty to respect and “protect” women and prevent gendered violence. In contrast to these celebratory representations, working-class men appear as potential villains, their masculinity laced with unmistakable connotations of danger. While these representations are not necessarily radically new in their class and caste bias, they are significant markers of the ascendant ideal man as middle-class/upper-caste, while simultaneously erasing the working-class/migrant/rural/lower-caste male body from popular public discourse. Performance of an ideal masculinity by fighting for women’s safety and protecting them has been a crucial trope of manly behavior in Hindi cinema through the post-independence period, as the brawny, muscular male protagonist protects women’s honor through exercise of strength, an obvious act of patriarchal patronage. However, this act now is cast in a modified avatar: it is the urbane, professional, “civilized” middle-class man who commits himself to protecting women’s rights to safety in public spaces, not necessarily through a show of muscular strength. In a context where spaces of consumption and leisure like malls, multiplexes and food courts are increasingly conflated with notions of “public space” in urban India, this discourse of masculinity becomes hyper-visible, imprinting itself forcefully on to these spaces in Indian cities, including in Pune (see Figures 1.3, 1.4, 1.5).

The celebration of the middle-class male figure in popular discourse is made obvious in a spate of advertisements29 in recent years which address upper-caste, middle-class men explicitly, emphasizing their duty to respect and “protect” women and prevent gendered violence. In contrast to these celebratory representations, working-class men appear as potential villains, their masculinity laced with unmistakable connotations of danger. While these representations are not necessarily radically new in their class and caste bias, they are significant markers of the ascendant ideal man as middle-class/upper-caste, while simultaneously erasing the working-class/migrant/rural/lower-caste male body from popular public discourse. Performance of an ideal masculinity by fighting for women’s safety and protecting them has been a crucial trope of manly behavior in Hindi cinema through the post-independence period, as the brawny, muscular male protagonist protects women’s honor through exercise of strength, an obvious act of patriarchal patronage. However, this act now is cast in a modified avatar: it is the urbane, professional, “civilized” middle-class man who commits himself to protecting women’s rights to safety in public spaces, not necessarily through a show of muscular strength. In a context where spaces of consumption and leisure like malls, multiplexes and food courts are increasingly conflated with notions of “public space” in urban India, this discourse of masculinity becomes hyper-visible, imprinting itself forcefully on to these spaces in Indian cities, including in Pune (see Figures 1.3, 1.4, 1.5).

As consumption (of commodities, lifestyles, ideologies, culture) becomes a fundamental axis along which gender/class/caste and regional/national identities are imagined and constructed in India today, the consolidation of the middle-class/upper-caste prototype of Indian male as the representative of Indian masculinity at the cost of the invisibilization of the regional/vernacular/working-class masculinity itself is also reflected overwhelmingly in this realm. It is against this erasure that Pune’s flex boards emerge as an important site for the expression of working-class masculinity.

It is relevant to note that flex boards are not typically erected in public space that is marked specifically for advertising, neither are the boards put up in paid spaces. While the city’s civic body does make specific public spaces available for purpose of advertising and for putting up of large hoardings, these (paid) spaces are usually occupied by advertisements of upmarket clothing, electronic or store brands, constituting a “formal” visual-scape of the city. The abundance of flex boards in the city’s public spaces, on street corners and in alleyways is in fact, on account of the fact that these spaces are not paid for. Collectives or individuals simply erect a flex board on the side of the road and pull it down after a few days. In technical terms, flex boards are considered to be “encroachments” on the city’s public space. Flex boards are a topic for furious hand-wringing for civic-minded citizens, as the former are considered to be occupying the realm of the “illegal” and as “defacing the city”30 leading to repeated calls for disciplinary action to be taken against those who erect the flexes and encroach on the city’s public spaces. The larger context of indeterminacy of property regimes in urban India and the porous boundaries between legal, illegal and extra-legal uses of urban space spawns forth a wide range of practices of appropriation and claiming of urban land by refugees, squatters, migrant labour or ethnic groups for residential, religious, economic or political purposes. Recent perspectives in anthropology and urban planning however, emphasize upon these practices of appropriating urban space as sites of subaltern resistance to hegemonic imaginations and structuring of cities, a crucial reclamation of the city space by its subaltern publics.31 Thus the discursive and material significance of flex boards in the city scape itself is already strongly marked by connotations of subaltern subversion. It is not mere coincidence then, that flex boards constitute a site where subaltern, low caste men re-inscribe themselves into the city’s space and its imagination, against the background of their increasing marginalization from the same.

Locating Pune

My research is set in the western Indian city of Pune, the next biggest city after Mumbai in the state of Maharashtra. With a population of 3.7 million,32 the city considers itself to be the educational and cultural center of the state. Pune’s rise as an urban center can be traced back to the rule of the Peshwa dynasty between 1720 and 1818;33 the Peshwas, who were the de facto upper-caste Brahmin rulers of the vast Maratha-ruled territories in eighteenth century India, made Pune their capital city in 1720, and over the following century, transformed it into a major bureaucratic-military center, imprinted with a distinct Brahminical cultural and social ethos.34 Peshwa rule represented the near-complete hegemony of Brahmin state authority, manifested in unconditional privileges and protection granted to the Brahmin community by its rulers. This pattern persisted until the present day in the spatial organization of the city, which pivots around the axis of caste: predominantly upper-caste Brahmins inhabit the prosperous parts of the city, while the eastern blocks of the city continue to be populated by lower-caste and Dalit communities and Muslim communities. In the last two decades, the city’s economic landscape has shifted to post-industrial ‘knowledge’ and service-oriented activities like multinational-owned information technology (IT) hubs, pharmaceutical companies, business process outsourcing companies (BPOs) and bio-technology firms. These developments have been facilitated by the skilled labor pool supplied by the city’s numerous prestigious research and educational institutions.35 These shifts have accompanied several changes in the cityscape, akin to the transformations in several metropolitan and smaller cities in India in the last decade. Pune has now acquired a new aspirational landscape consisting of high-end places of leisure and consumption and an increasingly class-segregated spatial regime (via gated communities), mapped onto its earlier geography of exclusion. A quick look at the history of housing in Pune shows that high proportion of Dalit castes remain concentrated in the city’s slums.36 Of the 43% of Pune’s population which resides in slums, the majority are Dalits and members of Scheduled Tribal groups.37

Claiming the Cityscape

It is against the above background of a distinctly caste-based geography of exclusion that the ethnographic and the visual data in this paper must be considered. In this section I present visual data which documents the peculiar practice that has come to increasingly characterize local politics across urban and rural India: putting up large and small flex boards in the city’s public spaces to mark a special occasion including national holidays, birthdays or death anniversaries of popular leaders or politicians, and religious celebrations. Flex boards are usually sponsored by an individual, a youth collective or a neighborhood association,38 whose name and photograph also appear prominently on the flex boards along with a message directed to the citizenry or to a local political leader being greeted/supported (whose image will also appear prominently). The ability to cheaply print flex boards that has arisen in the last decade has changed the nature of local political practice in important ways. The affordability of large size flexes allows them to be put up easily by even those who do not enjoy local political clout. Flex boards are now a constant presence in the visual regime of the cityscape, looming at traffic intersections, in prominent squares, lining neighborhood streets or at major junctions in the city (See Figures 2.3, 2.4).

Of course, flex boards are but one element of the visual material that populates the cityscape. Pune’s landscape, like most urban Indian landscapes, is a rich repository of popular visual imagery that ranges from religious and nationalist iconography to advertising local and upmarket brands to film posters, statues of leaders of national and local importance and quirky Marathi signage which testifies to the popular, caste-specific image of a particular (Brahmin) Puneri resident as one who is unfriendly and entitled, armed with sharp barbs and taunts (see Figures 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, 2.1 and 2.2). Most of the above mentioned categories of visual material can be closely read in order to see how they derive from a historical, material context of the city-space/region, and how they produce and sustain a distinctly gendered and caste-specific visual regime which imbues the city with its ethos, through their inclusions and erasures. It is beyond the purview of this paper, however, to illustrate how these competing visual regimes intersect to produce normative gendered ideals for its citizens. Neither do I want to suggest simplistically that flex boards respond directly or indirectly to the masculine imagery prevalent in the abovementioned overlapping visual cues in the city. However, this attempt to analyze the flex boards as spaces of gendered self-making can provide us with further clues in order to explore the semiotic import of a city’s visual scape in the making of its citizens’ gendered, caste-d and class-ed selves.

Pune’s history as a Brahminical city and its location in western Maharashtra implies that this context is also populated with a range of masculine archetypes, undergirded by the region’s caste contours. The presence of the figure of the 17th-century warrior king Shivaji, depicted as a wily, courageous fighter and ideal statesman, looms large over the masculine horizon of Maharashtra, and can be easily identified as a model of hegemonic masculinity who defines the ideals of manhood associated with the region as a whole. This warrior king, who belonged to the warrior Maratha caste, was instrumental in successfully defeating the Mughal rulers in the 17th century, thus forming an independent Marathi kingdom located in what is today roughly the territory of Maharashtra. Over the last five decades the figure of Shivaji has ascended to be Maharashtra’s most prominent icon: his name was claimed by a political party formed in the 1970s, Shiv Sena (translated roughly as “the army of Shivaji”) which has consistently relied on hyper-masculine, xenophobic, anti-Muslim rhetoric in its rise to power in the state. Shivaji’s appropriation into the complex caste politics of the state has also meant that his figure is claimed and evoked by all caste groups and political parties. Shivaji pervades the popular cultural referents of urban and rural Maharashtra in the form of a figure who is an unequivocally hyper-masculine, martial statesman and a cultural symbol of Marathi identity itself.

At the same time, other caste-specific versions of gendered ideals can be easily located in the figures of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the icon of Dalit emancipatory movement in mid-20th century and the author of India’s constitution and in the figures of Annabhau Sathe and Lahuji Salwe, leaders increasingly appropriated by youth from another Dalit caste, the Matangs, as their idols. The contours of these figures and their gendered attributes are shaped to a large extent by the ways in which their respective caste groups are increasingly asserting their caste identities in a distinctly masculinized idiom. Pune’s Brahminical past and its location as a stronghold of the right wing cultural organization, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) throws up its own set of ideals of manliness, embodied in the figure of the Sangh volunteer, typically dressed in khaki shorts and a white shirt, wielding a lathi (wooden stick) and engaged in a military-style drill, in their daily morning meets in neighborhoods of the city.

The point behind these descriptions is not to provide an inventory of “models of masculinity” that shape the cultural, political and gendered contexts of Pune and the larger region. Neither is there a single hegemonic masculine ideal, which seems to be the dominant ideal, in relation to other “subordinate masculinities”39 in the region. To read these contesting ideals of manhood within fixed boundaries of “hegemonic” and “subordinate” does not allow us to see how gendered performances of manliness across caste groups might be far more fluid, allying with hegemonic masculine ideals and challenging them simultaneously or subscribing to multiple ideals in multiple contexts. This description rather attempts to outline the existent repertoire of gendered ideals of manliness which mark the social and historical context of Pune and the region as a whole. How the specific markers of masculinity are represented in the flex boards articulated to these specific ideals is a topic for a much larger research project.

Through their presence in the material spaces of the city flex boards constitute distinct “spaces for representation”40 which fulfill the dual role of declaring one’s political allegiance as well as making oneself visible (literally and figuratively) on the horizons of local politics, in ways that are highly gendered and class-specific. The following images show how these flex boards are a rich repository of popular motifs of masculinity as they circulate in and dominate public spaces in contemporary urban Maharashtra. Figure 2.5 is a tribute to the man pictured, pehelwan (wrestler) Rajesh Barguje, and sponsored by a male collective called Gokul Group.41 The tag line above Barguje’s image is a play on two Hindi words, “naam” (name/fame) and “kaam” (work/task). It suggests that “Your work should earn you fame, and you should earn so much fame that just your name ensures the success of any work you undertake.” The presence of the Maratha icon Shivaji is a highly suggestive one, central to attributing masculine power to the person who features in the flex. The juxtaposition of images of Shivaji, a roaring lion and the smiling wrestler, affectionately referred to as “Master,” (meaning Guru/mentor) in this image is remarkable. In doing so, the image casts the achievement of success and fame in an unmistakably masculinized idiom.

Even more suggestive is the tagline, which exhorts the readers to earn fame which will open doors to success magically just by the power that their name will carry. This trope of understanding power is a highly class-specific one in the context of contemporary urban India. It refers to a realm where the weight carried by a name makes a difference and can be an adequate condition for the fulfillment of any necessary task. Recent research on urban South Asia focuses on the informal modalities as a methodological imperative for understanding social processes and urban experience in South Asia. Roy argues that informality in the realms of housing, land and in acquiring the resources needed for urban survival highlights the entrepreneurial resourcefulness and collective political agency of the urban poor to expertly exploit the porous divisions between the legal and illegal realms to survive in the city.42 Simone’s work on cities in Africa is also extremely relevant to understanding the lives of Indian cities: Simone demonstrates how informality is a way of life itself in urban Africa, as city dwellers continually plug into (and out of) fragmented, ephemeral networks of people, resources, objects and connections in order to survive in hostile and resource-deprived urban contexts.43 The notion of informality thus equips us to understand the process of how the urban poor in the global South “make things work” in the face of their own marginalized positions in the city’s economic, political and cultural life; this process is essentially contingent, unstable and works in the interstices of formal authority and informal ways of bypassing it. In my ethnographic research in the Dalit, working-class neighborhood of the Shellar galli, it was clear that several important resources – such as licenses for food vending carts, permission for extra water supply lines, and contracts for managing parking lots and several such “kaam” (tasks) – could only be achieved through informal contacts with the local municipal councillors or through maneuvering lower level council bureaucracy. Against this background, we can appreciate how central a name’s weight can be to get any kaam done; naam, (name) condenses within it not just clout, but the power of networks and the ability to maneuver these expertly for one’s own benefit. Moreover, it is the masculine forms of sociality and mobility that make possible the ability to construct, sustain and nurture these informal ties and networks in the Indian context, thus making informality a highly masculinized terrain.44 The ability to “get things done” through just the mention of one’s name thus becomes an index of one’s degree of manliness, specific to the urban poor and working-class sections, as reflected in the flex dedicated to the wrestler in Figure 2.5.

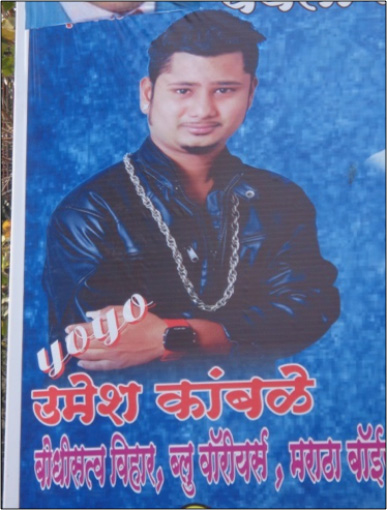

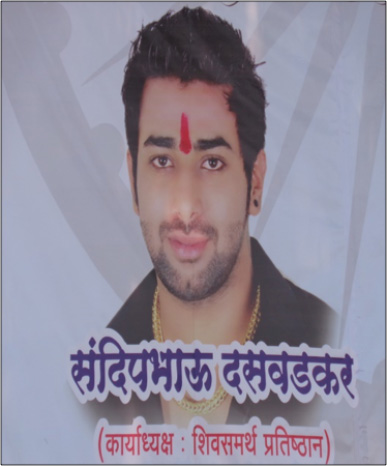

Many of the young men featured in the flex boards pay special attention to their bodily presentation, in terms of their pose, the clothes they wear, their accessories and the messages that accompany their images (see Figures 2.6, 2.7, 2.8). Figure 2.6 is a close-up of one young man who featured in a flex put up in one of the bigger and busier crossings in the city. The prominent inclusion of his nickname, “Yoyo,” signals his resemblance to the extremely popular Punjabi singer Yo Yo Honey Singh. His dark leather jacket, the thick chain displayed prominently around his neck, the stone stud earring in his right ear and his sideburns are all deployed to further emphasize the similarity between this young man and the popular singer. These accessories also signal a certain flamboyance of style and a familiarity with the latest trends in the world of fashion. Figures 2.7 and 2.8 also illustrate a characteristic style of bodily presentation and style in the flex boards: the wearing of a heavy gold chain against a dark shirt. The vermillion mark on the forehead is also a prominent marker of a traditional masculine comportment in the context of Maharashtra. Both the young men in above images also have accessories like a tattoo or an earring, as well as slickly gelled hair.

The nomenclature adopted by some of the youth collectives – and displayed boldly on their flex boards – suggests the nature of the aspirations they harbor (see 2.9). Some of the names of such youth collectives include “Rock Star Group,” “Enjoy Group,” “Jolly Group,” “Naughty Boys Group,” “No Fear Group,” “Meet Your Maker Group” and so on. The names adopted by some of these youth collectives or neighborhood associations testify to a profound desire to sound/look Anglicized. At the same time, these names are also heavily gendered in their framing, referring to masculine qualities of courage on the one hand and of a carefree, youthful “boys will be boys” idiom on the other.

The nomenclature adopted by some of the youth collectives – and displayed boldly on their flex boards – suggests the nature of the aspirations they harbor (see 2.9). Some of the names of such youth collectives include “Rock Star Group,” “Enjoy Group,” “Jolly Group,” “Naughty Boys Group,” “No Fear Group,” “Meet Your Maker Group” and so on. The names adopted by some of these youth collectives or neighborhood associations testify to a profound desire to sound/look Anglicized. At the same time, these names are also heavily gendered in their framing, referring to masculine qualities of courage on the one hand and of a carefree, youthful “boys will be boys” idiom on the other.

Lukose’s research on the engagement of Malayali youth with consumption in neoliberal Kerala also resonates with this emphasis on being carefree and pleasure-seeking, an imperative which she argues is a deeply gendered one. Elaborating upon the slang word, “chethu” she demonstrates how this term condensed a distinct practice of commodified masculinity among lower caste, working-class Malayali young men. Chethu, which referred figuratively to “hip,” “sharp” or “cool,” was a term used by young men to refer to a certain style quotient manifested by wearing jeans, cotton shirts and sneakers or in a fancy bike or a flashy car. Chethu, however, also encompassed considerations of status evidenced in easy cash, an Anglicized comportment, a flaneur-esque consumption of public spaces like the beach or the beer parlor, and an aspirational orientation towards life marked by youthfulness, enjoyment, and a staunch rootedness in the present moment.45 However, girls wearing westernized clothes would never qualify as chethu; they would be referred to as having “gema,” as being arrogant or a show-off,46 a clear indication of the starkly masculine contours of chethu.

Lukose’s research on the engagement of Malayali youth with consumption in neoliberal Kerala also resonates with this emphasis on being carefree and pleasure-seeking, an imperative which she argues is a deeply gendered one. Elaborating upon the slang word, “chethu” she demonstrates how this term condensed a distinct practice of commodified masculinity among lower caste, working-class Malayali young men. Chethu, which referred figuratively to “hip,” “sharp” or “cool,” was a term used by young men to refer to a certain style quotient manifested by wearing jeans, cotton shirts and sneakers or in a fancy bike or a flashy car. Chethu, however, also encompassed considerations of status evidenced in easy cash, an Anglicized comportment, a flaneur-esque consumption of public spaces like the beach or the beer parlor, and an aspirational orientation towards life marked by youthfulness, enjoyment, and a staunch rootedness in the present moment.45 However, girls wearing westernized clothes would never qualify as chethu; they would be referred to as having “gema,” as being arrogant or a show-off,46 a clear indication of the starkly masculine contours of chethu.

Consumption (of clothes, styles of dressing, bikes, accessories, social media) as a site of fashioning masculine identity has been the theme of a sizeable chunk of research in recent times. Chopra, Osella and Osella47 and De Neve48 highlight practices of consumption through which men construct themselves in the image of masculine ideals of “householder”/“patron,” etc. in Kerala and Tamil Nadu respectively. Rogers and Anandhi, Jeyaranjan and Krishnan49 explore consumption as an axis along which caste hierarchies are challenged or reinforced in Tamil Nadu. In rural Uttar Pradesh, educated Jat men seek to establish distance from rural agricultural laborers by riding motorcycles, wearing designer watches or chino-style trousers.50 It is crucial to note that the imaginary of modernity is an important constituent of the masculine identity these subjects seek to construct through practices of consumption. The flexes above are also an important site of self-making for the young men, in terms of portraying themselves as consumers of a certain modern style, clothing and accessories or in the Anglicized nomenclature of their “groups.” However, it is crucial to emphasize here that this style and idiom of consumption is starkly different from the idiom that is flashed across urban India today, via its glitzy malls, upmarket restaurants, foreign branded stores and high-end accessories and set apart from the kind of consumption that manifested in the advertisements specified in the preceding section.

Consumption (of clothes, styles of dressing, bikes, accessories, social media) as a site of fashioning masculine identity has been the theme of a sizeable chunk of research in recent times. Chopra, Osella and Osella47 and De Neve48 highlight practices of consumption through which men construct themselves in the image of masculine ideals of “householder”/“patron,” etc. in Kerala and Tamil Nadu respectively. Rogers and Anandhi, Jeyaranjan and Krishnan49 explore consumption as an axis along which caste hierarchies are challenged or reinforced in Tamil Nadu. In rural Uttar Pradesh, educated Jat men seek to establish distance from rural agricultural laborers by riding motorcycles, wearing designer watches or chino-style trousers.50 It is crucial to note that the imaginary of modernity is an important constituent of the masculine identity these subjects seek to construct through practices of consumption. The flexes above are also an important site of self-making for the young men, in terms of portraying themselves as consumers of a certain modern style, clothing and accessories or in the Anglicized nomenclature of their “groups.” However, it is crucial to emphasize here that this style and idiom of consumption is starkly different from the idiom that is flashed across urban India today, via its glitzy malls, upmarket restaurants, foreign branded stores and high-end accessories and set apart from the kind of consumption that manifested in the advertisements specified in the preceding section.

In their analysis of a Tamil hit film released in 1996, Kaadalan (Lover boy), Dareshwar and Niranjana trace the material and ideological components of this idiom of consumption to the moment of liberalization of Indian economy, beginning 1991.51 They point out that the film produced a fashion-conscious, MTV sensibility for lower-caste men, marked by a combination of baggy pants, blue jeans, rap music and Michael Jackson-like dance moves, portraying a distinct youthful energy through its use of colors and fashion.52 While until that time, it was the upper-caste, middle-class men’s and women’s bodies that constituted the space for the production of the consumerist aesthetic and ethos of globalizing India, this film signaled an important shift “…where globalization and its signifiers attach themselves to the body of the male lower-caste ‘youth’.”53 The modes of self-making evident in the flexes in Pune can be said to partially belong to this shift, where the young men, through their careful display of accessories of consumption like cell phones, clothes, hair style, tattoos and group nomenclature inscribe their caste and class selves into the narrative of consumption, hitherto so heavily dominated by bodies marked distinctly as upper-caste and upper-class. This inscription of lower caste/class bodies into the narrative of consumption in turn serves to reconfigure the idiom of consumption itself, which is increasingly cast in a class-specific and caste-specific imaginary. It is these highly localized imaginaries of consumption which continue to consolidate on the flex boards in Indian cities today.

In their analysis of a Tamil hit film released in 1996, Kaadalan (Lover boy), Dareshwar and Niranjana trace the material and ideological components of this idiom of consumption to the moment of liberalization of Indian economy, beginning 1991.51 They point out that the film produced a fashion-conscious, MTV sensibility for lower-caste men, marked by a combination of baggy pants, blue jeans, rap music and Michael Jackson-like dance moves, portraying a distinct youthful energy through its use of colors and fashion.52 While until that time, it was the upper-caste, middle-class men’s and women’s bodies that constituted the space for the production of the consumerist aesthetic and ethos of globalizing India, this film signaled an important shift “…where globalization and its signifiers attach themselves to the body of the male lower-caste ‘youth’.”53 The modes of self-making evident in the flexes in Pune can be said to partially belong to this shift, where the young men, through their careful display of accessories of consumption like cell phones, clothes, hair style, tattoos and group nomenclature inscribe their caste and class selves into the narrative of consumption, hitherto so heavily dominated by bodies marked distinctly as upper-caste and upper-class. This inscription of lower caste/class bodies into the narrative of consumption in turn serves to reconfigure the idiom of consumption itself, which is increasingly cast in a class-specific and caste-specific imaginary. It is these highly localized imaginaries of consumption which continue to consolidate on the flex boards in Indian cities today.

Remarkably, it is in the figures of local male politicians that these localized imaginaries of consumption seem to materialize in their most spectacular avatar. In the following section I will illustrate how flex boards are an embodiment of class-specific markers of masculinity, deftly aligning consumption with the practice of local politics to construct an ideal man. Research in recent times has confirmed the value that “doing politics” has acquired in lower-class, lower-caste masculine context of contemporary India. Jeffrey54 and Jeffrey et al.55 demonstrate how local, low caste (male) youth in rural north India respond to unemployment by establishing themselves as netas (political leaders), engaging in local political brokering and networking, which provides the young men with a model of masculinity which incorporates the value of education, earning them respect. Also, Hansen demonstrates how the militant right wing party, Shiv Sena, in order to establish their stronghold on the city, effectively harnessed the aspirations and hopes of boys from poorer backgrounds, for whom being a part of the political party was instrumental in gaining money, power and status.56 Flex boards are thus a part of a larger process in urban India, wherein the acutely masculine terrain of the domain of politics, coupled with vulnerabilities of subaltern men, has given rise to a remarkable constellation of politics, class and masculine identity across contexts within the country. Presented below are instances of local political leaders in Pune who enjoy almost a cult following, a large part of it being their distinct style and their excessive consumption (Figures 2.11- 2.13). While reading the valence of these representations of these male politician figures, I find it helpful to re-visit some conversations during my doctoral field research in 2011 and given that these conversations make available to us an added layer of comprehension of these figures, in terms of young, low caste men’s own affective engagement with these representations of the political leaders.57 In the light of the fact that these political figures have continued to dominate the terrain of local politics in Pune for the past decade, these conversations hold significant relevance for the purpose of this paper.58

Wanjale (Fig. 2.11), a local politician, who allegedly wore two kilograms worth gold on his person, had earned the title, “The Gold Man” of Pune. He was described to me as a vagh (tiger) by several young men. In its tribute to the politician, a prominent Marathi newspaper noted Wanjale’s favorite quote, “Main dikhta hoon villain jaisa, lekin kaam karta hoon hero ka” (I look like a villain, but my deeds are those of a hero). I find it remarkable that Wanjale was acutely conscious of the embodied and a visual regime of attributing morality that prevails in the Indian context: the consistent association of lack of hygiene/morality with lower-caste/class bodies and bodies which appear as low-caste as opposed to the automatic attribution of an unquestioned moral subject-hood to bodies that looked like upper-caste bodies (fair complexioned/certain bodily comportment, etc.). The advertisements referred to in the preceding section which established the “goodness” of certain kinds of men in sharp contrast to the lack of it in certain others, are the most explicit manifestation of this visual regime of crediting bodies with unequal moral value. In an extremely suggestive instance, a report in a local newspaper laments the proliferation of flex boards across the city’s spaces as “unsightly banners, which detract from the aesthetic appeal of large trees, heritage structures and thoughtful architecture.” The article further goes on to say that, “…most of the faces on the banners and [bill invariably look like crooks in comic books. This is the ugly part.”59 While Wanjale displays awareness of this profoundly unequal casteist and classist graded system, he does not question it fundamentally, as he asserts his “hero”-like deeds despite his villainous appearance. Wanjale also inspired another politician to follow suit in terms of this display of gold. Samrat Moze, an aspiring politician, does not shy away from his penchant for wearing heavy gold ornaments. Claiming to wear eight kilograms of gold, Samrat Moze joined the Nationalist Congress Party in August 2012 (see Figure 2.12).

In December 2012, Datta Phuge, a chit fund manager from a suburb of Pune and a cadre of the Nationalist Congress Party, created a huge splash with his custom-made shirt of gold worth US$235,000 (See Figure 2.13). Phuge’s extravagance and obsession with gold received wide national and international media attention. It is crucial to note that none of the male politicians above correspond to the image of urbane, suave, English-speaking consuming male figure, with which we are now familiar. All these men in fact, belonged to the Maratha caste, which, though a dominant caste in Maharashtra (in terms of political power and financial prowess), does not enjoy the cultural capital claimed by the urban, professional Brahmin community. Flex boards as spaces for representation, however, can hardly be understood as constructing idealized manliness solely via the idiom of consumption. In the following part of this section, I focus on the instance of one politician in Pune and attempt to illustrate how his carefully managed public persona through flex boards and the urban legends generated by their actions consolidate an extremely seductive narrative of working-class and lower-caste masculine power for the young men, one which upholds a distinctly class-based moral ethic and values of loyalty and defiance.

Dheeraj Ghate (original name retained) is a prominent leader from the currently ruling right wing Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP), active in a central western administrative ward of the city of Pune. I was introduced to Dheeraj Ghate via his constant presence on flex boards in one particular crossing of the city, close to his headquarters (see Figure 2.14). Almost every week a new flex would be erected in this crossing, announcing a local welfare scheme that Ghate had advocated, or greeting the citizens for a religious occasion on behalf of Ghate. Close-ups of his face would be often displayed in these flexes, with creative tag lines, which sometimes were purported to be Ghate’s quotes.

During my research in Shelar galli, Ghate’s name surfaced in informal conversations with several young men, as they excitedly discussed the city-wide procession which marks the end of the ten-day long Ganesh festival. This procession is an important landmark in the city’s cultural landscape. Winding its way through the city’s arterial roads and lasting for 30 hours, several hundred neighborhood associations participate in this procession carrying tableaus dedicated to Lord Ganesh, accompanied by deafening music and feverish dancing. Inviting huge (and largely working-class male) crowds, these frenzied celebrations are now turning into a site of civic disciplinary action, as the former are increasingly represented in the city’s discourse as a nuisance, as noise pollution and as corruption of the religious essence of this festival. Against this background, it was interesting to note how the young men described how Ghate’s influence in the procession had gone unchallenged; he had easily flaunted the restriction on the decibel level of the music, ignoring warnings of police action. Some of the older men then recounted how in the year 2011, Ghate was the only one who had dared to publicly screen the World Cup cricket match between India and Pakistan, when the police had specifically banned all public screenings due to the possibility of communal tensions erupting. When I asked about why they all looked up to him so much, one young man named Rama said “To sagla baghto tyancha. Kapde, boot, khanya paasun” (He looks after “his boys” completely, right from their clothes and shoes to their meals).

Rama went on to describe Ghate’s headquarters to me: it was stocked with minor weapons like clubs and sticks; he explained how Ghate just needed to signal to one of “his boys” and he would be surrounded with a protective ring of his boys within a flash. These narratives helped consolidate Ghate’s status not just as a man who dared to defy the civic authority, but importantly as a man who dared to defy the authority in defense of the interests of young men like those in Shelar galli, as a man who cared about what these young men liked, enough to defy the authority’s orders. Ghate representation as a nurturing patron was underlined even more markedly in Rama’s description: in referring to the younger cadre of Ghate’s party as the Ghate’s boys, Rama clearly indicated an entrenched relationship of patronage between Ghate and his young cadre, with the former providing for all the latter’s basic needs. There was an unmistakable sense of romance with which Rama had described how Ghate’s boys surrounded him with a protective ring just at his signal. The ability to command unflinching loyalty from other men is the other crucial trope that established Ghate as an ideal man in the eyes of the young men in Shelar galli. These narratives, circulating amongst the young subaltern men across the network of neighborhood associations in the city, thus have the power to signify the figure of the politician with explicitly masculinized virtues of benevolent patronage and protection. In a similar vein, in another conversation the young men in Shelar galli admitted that Ramesh Wanjale’s gold was earned through “don numbercha paisa,” (through illicit means); but they hastened to clarify that “Pan garibancha chorlela nhavta” (It was not stolen from the poor). This Robin Hood-esque representation rendered Wanjale as sympathetic to the cause of the subaltern, while simultaneously beating the dominant at their own game (of gaining and flaunting wealth).

The construction of Dheeraj Ghate as a fearless mentor who earned young men’s loyalty finds striking resonances in Hansen’s research on Shiv Sena in Mumbai. Hansen describes the almost mythical aura constructed around a local Shiv Sena leader, Dighe saheb, to whom “superhuman”60 qualities are attributed. Hansen contends that Dighe saheb’s carefully cultivated image was more than just a political gimmick; it also represented the aspirations of scores of young boys who adored Dighe and who sought to replicate the narrative of his journey from humble origins to a place where he commanded enormous power, status and blind loyalty of local boys. The boys’ dreams of a bright future entailed a transformation “…from a ‘nobody’ to a local ‘somebody’.”61 (See Figures 2.15, 2.16, and 2.17)

In representing Ghate simultaneously as the “king,” “son,” “brother” and an “efficient administrator,” (Figures 2.15 and 2.16) these flexes tie together the disparate realms of familial duty and civic duty, evoking a subject-king relationship and citizen-administrator relationship together in a heavily masculinized single ideal embodied by the politician. The flex boards, however, do not merely serve to construct the figure of the benevolent protector enmeshed with a modern administrator; the images above also are significant indicators of the ways in which the young men sponsoring the flexes represent themselves as being aligned with the powerful masculine figure, thus seeking to establish proximity with the power and values that the latter represents (Figures 2.16 and 2.17). Flexes, then, serve not just to construct an idealized masculinity through the figure of the politician, but are also the site of an explicit, public performance of alignment with an idealized masculinity.

Conclusion

This paper has attempted to explore the visual regime of flex boards in urban India as a crucial site for gendered self-making for working-class/lower-caste men in neoliberal urban India. I argue that the proliferation of the flex boards across the city’s landscape is signifies an attempt to gain visibility in a new urban order in India which celebrates only certain kinds of bodies (upper-caste/middle-class, English-speaking) and certain kinds of idioms of consumption (mall-centric, brand-centric) as those who legitimately “belong” to the city or as those who can represent the face of the new city (and consequently the new nation). The flexes and the images of the young men that they carry, disrupt continually these hegemonic narratives of neoliberal citizenship. They do so by physically inserting themselves in the city’s public spaces: bodies which do not conform to the upper-caste, middle-class aesthetic and the latter’s modes of consumption. In doing so, the flex boards in the public spaces of the city also become subversive spaces where a class and caste specific gendered masculine self is imagined and performed.

While the flex boards allow subaltern men in the city to perform masculinity via consumption specific to their caste and class locations, the fast incorporation of flex boards into the repertoire of urban local politics also means that flex boards enable the articulation of idioms of masculinity within the imagination of political participation in the city today. For the young men who hire and feature in the flex boards, their aspiration towards becoming/aligning with a political leader becomes imperceptibly enmeshed with their imaginations of an ideal masculinity, shaped by values of loyalty, fearlessness, benevolence, flamboyance, and ostentatious display of wealth.

However, any argument about the flex boards as a space of disruption of the hegemonic narratives of citizenship in neoliberal Pune has to be equally mindful of the fact that flex boards are as much a site of a hyper-masculine, patriarchal constructions of the gendered self, premised on the exclusion of women from the arena of politics and participation in these intricate networks of local political dynamics. Any analysis has to be cautious of romanticizing this aspect, while at the same time focusing upon its subversive potential. Thus while claiming the city’s material (and social) spaces for representing themselves, men behind (and on) the flexes also end up masculinizing the city’s spaces acutely in discursive terms, rendering the latter unequally available to women, especially lower-caste/working-class women of the city. Flex boards as an iconography of urban masculinity then, condense within their visuals the stark articulations between class- and caste-specific ideals of manliness and neoliberal urban processes; the exclusionary aspect of these rich sites of gendered self-making, however, continues to highlight the contradictory nature of urban transformations themselves, of which the flex boards are but an artefact.

List of References

Alter, Joseph. S. The Wrestler’s Body: Identity and Ideology in North India. Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford: University of California Press, 1992.

Anandhi, S., J.Jeyaranjan, R. Krishnan. “Work, Caste and Competing Masculinities: Notes from a Tamil Village.” Economic and Political Weekly 37, no.24 (2002): 4403-4414.

Athique, Adrian and Douglas Hill. The Multiplex in India: A Cultural Economy of Urban Leisure. Oxon, New York: Routledge, 2010.

Banerjee, Sikata. “Gender and Nationalism: The Masculinization of Hinduism and Female Political Participation in India.” Women’s Studies International Forum 26, no.2 (2003): 167-179.

Basant, Rakesh and Pankaj Chandra. “Role of Educational and R & D Institutions in City Clusters: An Exploratory Study of Bangalore and Pune Regions in India.” Ahmedabad: Centre for Innovation, Incubation and Entrepreneurship, Indian Institute of Management, 2007.

Census of India. “Population Details.” Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, 2011. Accessed December 3, 2015.

Connell, R.W. Masculinities. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, (2nd edition), 1995.

Dasgupta, Chaitali. “Friends: The Neighbourhood Boys Club.” In From Violence to Supportive Practice: Family, Gender and Masculinities in India, edited by R. Chopra, 101-127. New Delhi: United Nations Development Fund for Women, 2002.

De Neve, Geert. “The Workplace and the Neighbourhood: Locating Masculinities in the South Indian Textile Industry.” In South Asian Masculinities: Context of Change, Sites of Continuity, edited by R. Chopra, C. Osella, and F. Osella, 60-95. New Delhi: Kali for Women and Women Unlimited, 2004.

Derne, Steven. Movies, Masculinity, and Modernity: An Ethnography of Men’s Film Going in India. Westport,Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Desai, Renu and Romola Sanyal, eds. Urbanizing Citizenship: Contested Spaces in Indian Cities. New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2012.

Deshpande, Rajeshwari. “How much does the City help Dalits? Life of Dalits in Pune: Overview of a Century.” Indian Journal of Social Work 68, no.1 (2007): 130-151.

Dhareshwar, Vivek and Tejaswini Niranjana. “Kaadalan and the Politics of Resignification: Fashion, Violence and the Body.” Journal of Arts and Ideas 29 (1996): 5-26.

Falzon, Mark-Anthony. “Paragons of Lifestyle: Gated Communities and the Politics of Space in Bombay.”City & Society 16, no. 2 (2004): 145-167.

Faust, David, and Richa Nagar. “Politics of Development in Postcolonial India: English-Medium Education and Social Fracturing.” Economic and Political Weekly 36, no. 30 (2001): 2878-2883.

Fernandes, Leela. “The Politics of Forgetting: Class Politics, State Power and the Restructuring of Urban Space in India.” Urban Studies 41, no. 12 (2004): 2415-2430.

Ghertner, Asher. “Rule by Aesthetics: World-Class City Making in Delhi.” In Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global, edited by A. Roy, and A. Ong (First Edition), 279-306. UK: Blackwell Publishing Limited, 2011.

Ghertner, Asher. “Nuisance Talk: Middle-Class Discourses of a Slum-Free Delhi.” In Ecologies of Urbanism in India: Metropolitan Civility and Sustainability, edited by A. Rademacher and K. Sivaramakrishnan, 249-275. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013.

Gokhale, B.G. Poona in the Eighteenth Century: An Urban History. Oxford, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Hansen, Thomas Blom. Wages of Violence: Naming and Identity in Postcolonial Bombay. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Indukuri, Sirisha. “Veiled Men: Male Domestic Workers.” In From Violence to Supportive Practice: Family, Gender and Masculinities in India, 63-80. New Delhi: United Nations Development Fund for Women, 2002.

Jeffrey, Craig. Timepass: Youth, Class, and the Politics of Waiting in India. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2010.

Jeffrey, Craig, Patricia Jeffery, and Roger Jeffery. Degrees Without freedom?:Education, Masculinities, and Unemployment in North India. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Kosambi, Meera. “Glory of Peshwa Pune,” review of Poona in the Eighteenth Century by B.G. Gokhale, Economic and Political Weekly 24, no. 5 (1989): 247-50.

Lukose, Ritty. Liberalization’s Children: Gender, Youth, and Consumer Citizenship in Globalizing India. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2009.

Lukose, Ritty. “Consuming Globalization: Youth and Gender in Kerala, India.” Journal of Social History, 38, no. 4 (2005): 915-935.

McDuie-Ra, Duncan. “Being a Tribal Man from the North-East: Migration, Morality and Masculinity.” In Gender and Masculinities: Histories, Texts and Practices in India and Sri Lanka, edited by A. Doron, and A. Broom, 126-148. Delhi: Routledge, 2014.

Mehta, Deepak. “Collective Violence, Public Spaces and the Unmaking of Men.” Men and Masculinities 9 (2006): 204-225.

Mitchell, Don. The End of Public Space? People’s Park, Definitions of Public and Democracy, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 85 (1995): 108-133.

Osella, Caroline and Filippo Osella. Men and Masculinities in South India. London, New York, Delhi: Anthem Press, 2006.

Phadke, Shilpa. “Unfriendly Bodies, Hostile Cities: Reflections on Loitering and Gendered, Public Space.” Economic and Political Weekly XLVIII, no. 39 (2013): 50-59.

Ramaswami, Shankar. “Masculinity, Respect and the Tragic: Themes of Proletarian Humor in Contemporary Industrial Delhi.” International Review of Social History 51, no. S14 (2006): 203-227.

Ray, Raka. “Masculinity, Femininity, and Servitude: Domestic Workers in Calcutta in the Late Twentieth Century.” Feminist Studies 26, no. 3 (2000): 691-718.

Rogers, Martyn. “Modernity, ‘Authenticity,’ and Ambivalence: Subaltern Masculinities on a South Indian College Campus.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 14 (2008): 79-95.

Roy, Ananya. “Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35, no. 2 (2011): 223-38.

Roy, Ananya. “Why India cannot Plan its Cities: Informality, Insurgence and the Idiom of Urbanization.” Planning Theory 8, no.1 (2009): 76-87.

Roy, Ananya. City Requiem, Calcutta: Gender and the Politics of Poverty. New Delhi: Pearson Education. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Simone, Abdoumaliq. For the City Yet to Come: Changing African Life in Four Cities. USA: Duke University Press, (Kindle Edition), 2004.

Sinha, Mrinalini. Colonial Masculinity: The ‘Manly Englishman’ and the ‘Effeminate Bengali’ in the Late Nineteenth Century. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1995.

Srivastava, Sanjay. Entangled Urbanism: Slum, Gated Community, and Shopping Mall in Delhi and Gurgaon. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Srivastava, Sanjay. “‘Sane Sex,’ the Five-Year Plan Hero and Men on Footpaths and Gated Communities: On the Cultures of Twentieth-Century Masculinity.” In Masculinity and Its Challenges in India: Essays on Changing Perceptions, edited by R.K. Dasgupta and K.M. Gokulsing, Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc., Publishers, Kindle Edition, 2014.

Tiwari, Noopur. “How Not to Think about Violence against Women.” Kafila, December 24, 2012. Accessed December 9, 2014. https://kafila.online/2012/12/24/how-not-to-think-about-violence-against-women-noopur-tiwari/

Waldrop, Anne. “Gating and Class Relations: The Case of a New Delhi ‘Colony’.” City and Society 16, no. 2 (2004): 93-116.

Endnotes

1 All the names identifying specific neighborhoods and people in this paper have been changed (unless otherwise specified), in order to protect the identity of the interlocutors. The name of the city of Pune, however, remains unchanged.

2 Galli in Marathi, the native language of the state of Maharashtra, refers to a narrow alleyway. The older part of the city, divided into wards known as Peths are typically marked by thousands of narrow crisscrossing gallis. Most residents in Moti Peth where I conducted my fieldwork referred to their neighborhood simply as galli or Shelar galli, referring to the Shelar family who owned a large plot of land in this alleyway.

3 Dalit (“crushed” or “broken” in Marathi) refers collectively to castes formerly considered to be untouchable in India. This term of reference has a complex political genealogy, which seeks to recover a specific kind of a political subjectivity, wherein the denial of dignity and humiliation attached to being untouchable is secularized and re-signified into a positive political value and a politicized demand for justice and inclusion (Rao 2009: 1-3).

4 Bengali babu refers to the middle-class, English educated Bengali man, who typically held clerical positions in the imperial administrative system.

5 Mrinalini Sinha, Colonial Masculinity: The ‘Manly Englishman’ and the ‘Effeminate Bengali’ in the Late Nineteenth Century. (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1995), 2-4.

6 Sikata Banerjee, “Gender and Nationalism: The Masculinization of Hinduism and Female Political Participation in India.” Women’s Studies International Forum 26, no.2 (2003): 167-179; Thomas Blom Hansen, Wages of Violence: Naming and Identity n Postcolonial Bombay

7 The term “Five Year Plan” refers to India’s long-standing legacy of rational planning inherited from Soviet Union in the realm of economic development. India’s economic planning has been conducted through Five Year Plans beginning 1947.

8 Sanjay Srivastava, “‘Sane Sex,’ the Five-Year Plan Hero and Men on Footpaths and Gated Communities: On the Cultures of Twentieth-Century Masculinity.” In Masculinity and Its Challenges in India: Essays on Changing Perceptions, edited by R.K. Dasgupta and K.M. Gokulsing, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc., Publishers, Kindle Edition, 2014).

9 Craig Jeffrey, Timepass: Youth, Class, and the Politics of Waiting in India (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2010); Shankar Ramaswami, “Masculinity, Respect and the Tragic: Themes of Proletarian Humor in Contemporary Industrial Delhi.” International Review of Social History 51, no. S14 (2006): 203-227; Raka Ray, “Masculinity, Femininity, and Servitude: Domestic Workers in Calcutta in the Late Twentieth Century.” Feminist Studies 26, no. 3 (2000): 691-718; Geert De Neve, “The Workplace and the Neighbourhood: Locating Masculinities in the South Indian Textile Industry.” In South Asian Masculinities: Context of Change, Sites of Continuity, eds. R. Chopra, C. Osella, and F. Osella (New Delhi: Kali for Women and Women Unlimited, 2004), 60-95; Sirisha Indukuri, “Veiled Men: Male Domestic Workers.” In From Violence to Supportive Practice: Family, Gender and Masculinities in India, ed. R. Chopra (New Delhi: United Nations Development Fund for Women, 2002), 63-80.

10 Caroline Osella and Filippo Osella. Men and Masculinities in South India (London, New York, Delhi: Anthem Press, 2006); Ritty Lukose, Liberalization’s Children: Gender, Youth, and Consumer Citizenship in Globalizing India. (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2009).

11 R.K. Dasgupta and K.M. Gokulsing (eds.), Masculinity and Its Challenges in India: Essays on Changing Perceptions (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc., Publishers, Kindle Edition, 2014).

12 Duncan McDuie-Ra, “Being a Tribal Man from the North-East: Migration, Morality and Masculinity.” In Gender and Masculinities: Histories, Texts and Practices in India and Sri Lanka, eds. A. Doron, and A. Broom (Delhi: Routledge, 2014), 126-148.

13 Deepak Mehta, “Collective Violence, Public Spaces and the Unmaking of Men.” Men and Masculinities no.9 (2006): 204-225; Hansen, Wages of Violence

14 Craig Jeffrey, Timepass; Ritty Lukose, Liberalization’s Children; Ananya Roy, City Requiem, Calcutta: Gender and the Politics of Poverty (New Delhi: Pearson Education. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2003)

15 Joseph S. Alter, The Wrestler’s Body: Identity and Ideology in North India (Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford: University of California Press, 1992).

16 Steven Derne, Movies, Masculinity, and Modernity: An Ethnography of Men’s Film Going in India (Westport,Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2000).

17 Chaitali Dasgupta, “Friends: The Neighbourhood Boys Club.” In From Violence to Supportive Practice: Family, Gender and Masculinities in India, ed. R. Chopra. (New Delhi: United Nations Development Fund for Women, 2002), 101-127

18 Lukose, Liberalization’s Children; Leela Fernandes, “The Politics of Forgetting: Class Politics, State Power and the Restructuring of Urban Space in India.” Urban Studies 41, no. 12 (2004): 2415-2430.

19 Renu Desai and Romola Sanyal, eds. Urbanizing Citizenship: Contested Spaces in Indian Cities. (New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2012).

20 Adrian Athique and Douglas Hill. The Multiplex in India: A Cultural Economy of Urban Leisure (Oxon, New York: Routledge, 2010); Mark-Anthony Falzon, “Paragons of Lifestyle: Gated Communities and the Politics of Space in Bombay.” City & Society 16, no. 2 (2004): 145-167; Anne Waldrop, “Gating and Class Relations: The Case of a New Delhi ‘Colony’.” City and Society 16, no. 2 (2004): 93-116.

21 Sanjay Srivastava, Entangled Urbanism: Slum, Gated Community, and Shopping Mall in Delhi and Gurgaon. (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2015); Asher Ghertner, “Rule by Aesthetics: World-Class City Making in Delhi.” In Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global, eds. A. Roy, and A. Ong (UK: Blackwell Publishing Limited, 2011, First Edition), 279-306.

22 Asher Ghertner, “Nuisance Talk: Middle-Class Discourses of a Slum-Free Delhi.” In Ecologies of Urbanism in India: Metropolitan Civility and Sustainability, eds. A. Rademacher and K. Sivaramakrishnan, (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013), 249-275.

23 Shilpa Phadke, “Unfriendly Bodies, Hostile Cities: Reflections on Loitering and Gendered, Public Space.” Economic and Political Weekly XLVIII, no. 39 (2013): 50-59.

24 On the night of December 16, 2012, Jyoti Singh, a young paramedical student in Delhi boarded a privately operated bus after watching a movie with a male friend in the night. The privately run bus was empty save four young men who proceeded to rape Jyoti Singh and injure her brutally. While Singh succumbed to her injuries two weeks later, this incident triggered unprecedented mass protests across cities in India, especially in the capital city of Delhi, bringing into focus with a sudden urgency questions of gendered violence in Indian cities, state accountability and misogyny in Indian public culture. See https://kafila.online/tag/delhi-gang-rape/ for some insightful commentaries on this event and its implications.

25 Shilpa Phadke, “Unfriendly Bodies, Hostile Cities,” 50; Noopur Tiwari, “How Not to Think about Violence against Women.” Kafila, December 24, 2012.(Accessed December 9, 2014)

26 Phadke, “Unfriendly Bodies, Hostile Cities,” 51

27 Ibid., 52

28 Ibid., 55

29 NOTE here the Officer’s Choice Blue Label ad campaigns, etc.

30 See http://www.cityblogpune.com/2012/02/flex-ible-nusianace.html

31 See Renu Desai and Romola Sanyal, eds. Urbanizing Citizenship: Contested Spaces in Indian Cities. (New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2012); Ananya Roy, “Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35, no. 2 (2011): 223-38; Asef Bayat, “From ‘Dangerous Classes’ to ‘Quiet Rebels’: Politics of the Urban Subaltern in the Global South.” International Sociology 15 no. 3 (2000): 533-557.

32 Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, Census of India: Population Details, 2011.

33 B.G. Gokhale, Poona in the Eighteenth Century: An Urban History. Oxford, (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1988).

34 Meera Kosambi, “Glory of Peshwa Pune,” review of Poona in the Eighteenth Century by B.G. Gokhale, Economic and Political Weekly 24, no. 5 (1989): 247.

35 Rakesh Basant and Pankaj Chandra, “Role of Educational and R & D Institutions in City Clusters: An Exploratory Study of Bangalore and Pune Regions in India.” (Ahmedabad: Centre for Innovation, Incubation and Entrepreneurship, Indian Institute of Management, 2007).

36 Rajeshwari Deshpande, “How much does the City help Dalits? Life of Dalits in Pune: Overview of a Century.” Indian Journal of Social Work 68, no.1 (2007): 130-151.

37 Ministry of Home Affairs, GOI, Census of India, Population Details

38 Neighborhood associations/ youth collectives are a crucial presence in the public life of cities in western India, including in Pune. These associations are typically run exclusively by young male members within working-class and low caste neighborhoods with the explicit purpose of organizing collective religious/ cultural celebrations within the neighborhood. Apart from this, neighborhood organizations also constitute a fundamental node of the network of support that working-class and poor neighborhoods in urban India rely on in times of financial, medical or even domestic crises. Neighborhood associations are profoundly gendered and caste/ religion specific spaces in the city and have been the primary drivers of the popularity of the practice of putting up flex boards in the city’s spaces, to make visible their presence and their activities.

39 The usage “subordinate masculinity” has been a contribution of R. Connell (1995), who set the agenda for a critical view of masculinity, arguing for plurality of masculinities and power differentials within groups of men, thus taking the field beyond a simplistic, monolithic view of all men as being equally powerful, or as ascribing to a singular model of masculinity. The categories of “hegemonic masculinity,” “subordinate masculinity” and “marginalized masculinity” have been helpful in operationalizing these power differentials while analyzing men’s interrelationships and bringing in the vectors of race, class or ethnicity in the analysis of masculinity (71-85).

40 Don Mitchell, “The End of Public Space? People’s Park, Definitions of Public and Democracy,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 85 (1995): 123-4. Mitchell elaborates upon the concept of spaces for representation in the specific context of claiming of citizenship rights in cities. For him, visibility and representation are crucial aspects of claiming of citizenship rights, where groups or individuals can represent and make visible their needs and demand their rights from the state. From this view, public space becomes an ideal arena for claiming citizenship, with the former’s materiality ensuring visibility for the groups occupying the space and providing them with spaces for representation. However, spaces for representation, I argue, can be crucial for not just claiming of formal citizenship rights but also for claiming the substantive right to belong and to occupy space in the imagination of the city.

41 The name of the collective, partially obscured, appears in blue type on the left bottom side of the image.

42 Ananya Roy, “Why India cannot Plan its Cities: Informality, Insurgence and the Idiom of Urbanization.” Planning Theory 8, no.1 (2009): 76-87; Ananya Roy, “Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35, no. 2 (2011): 223-38.

43 Abdoumaliq Simone, For the City Yet to Come: Changing African Life in Four Cities. (USA: Duke University Press, (Kindle Edition), 2004).

44 Also see Ananya Roy, City Requiem, Calcutta: Gender and the Politics of Poverty (New Delhi: Pearson Education. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), for an elaboration of a masculinization of ties of political patronage in urban India.

45 Lukose, Liberalization’s Children, 66-70.

46 Lukose, Liberalization’s Children, 66.

47 Chopra, Osella and Osella, South Asian Masculinities

48 De Neve, “The Workplace and the Neighbourhood,” 60-95

49 Martyn Rogers, “Modernity, ‘Authenticity,’ and Ambivalence: Subaltern Masculinities on a South Indian College Campus.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 14 (2008): 79-95. S. Anandhi, J. Jeyaranjan, R. Krishnan. “Work, Caste and Competing Masculinities: Notes from a Tamil Village.” Economic and Political Weekly 37, no.24 (2002): 4403-4414.

50 Craig Jeffrey, Patricia Jeffery, and Roger Jeffery. Degrees Without freedom?:Education, Masculinities, and Unemployment in North India. (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2008).