Snapshots of Shôwa (CE 1926-89) and Post-Shôwa Japan Through Salaryman Articulations

REFERENCES | AUTHOR BIO | ![]() Download the PDF |

Download the PDF | ![]() Download the Accessible PDF

Download the Accessible PDF

Keywords: Japan, twentieth-century, twenty-first century, masculinity, hegemonic, masculinity, salaryman, historical overview, visual culture, film

Introduction1

Nations (and national identities) are constituted as much through ideologies of gender, both in relation to women and femininity, and men and masculinity, as other ideologies such as those of class or race or ethnicity.2 This applies to Japan, and the country’s processes of industrialization, modernization and nation-building from the late-nineteenth century during the Meiji Period (1868-1912), right through the Taishô (1912-1925), Shôwa (1925-1989) and post-Shôwa, Heisei (1989- ) periods of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.3

At one level “men” have historically been pivotal to discourses and ideologies on nations and nation-states.4 However, it was really not until the 1980s and 1990s that “masculinity” (and “men”) began being interrogated as a construct. A growing body of academic and non-academic literature started to draw attention to the reality that rather than being a fixed, biologically-determined essence, “masculinity” is constructed, shaped, “crafted” in response to socio-cultural, economic, political, and other considerations.5 Furthermore, rather than a singular form of masculinity, just one way of “being a man,” there are a myriad of masculinities, at any one time. Within these there are hierarchies of power defining the relationships between these various masculinities; the discourse of masculinity that has the greatest ideological power and hold may be thought of the hegemonic form of masculinity.6 The hegemonic form can be considered as a cultural “ideal” or “blueprint” which, by-and-large, cannot be perfectly attained by most men. Thus, it need not be the most common form, but it is normative in that what it does have in its favor is power and ascendancy achieved “through culture, institutions, and persuasion.”7 However, importantly, this is an ongoing, shifting process, as the discourse of hegemonic masculinity is constantly “crafted” and “re-crafted” in response to changing socio-economic, cultural, and political conditions.8

With this in mind, this paper looks at Japan over the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century, particularly over the Shôwa (1925—1989) and post-Shôwa, Heisei (1989— ) periods, through the framework of masculinity – specifically, through a discourse of hegemonic masculinity that, in many regards, came to signify Japanese national identity. The figure of the middle-class, white-collar salaryman (sarariiman) has occupied a prominent place in socio-cultural and economic narratives of postwar Japan. As a sort of “Everyman” of corporate Japan over the high economic growth decades of the 1960s through until the early 1990s, the salaryman came to signify both Japanese masculinity in general, and more specifically Japanese corporate culture. In this regard the discourse of masculinity signified by the salaryman could have been regarded as the culturally privileged hegemonic masculinity in postwar Japan. This was despite the reality that, even at the height of Japan’s economic ascendancy in the 1970s, only a minority of Japanese men would have fallen within the strictest definitional parameters of the category of “salaryman” – fulltime white-collar permanent employees of organizations offering benefits such as lifetime employment guarantee, salaries and promotions tied to length of service, and an ideology of corporate paternalism characterizing relations between the employee and the organization. However it was more a case that the discourse surrounding the middle-class salaryman, indeed the ideology associated with and embedded in the discourse,9 was far more extensive and pervasive in its reach. Consequently, over the crucial postwar decades from the 1960s through the 1980s, the salaryman could well have been considered to be what Vera Mackie has referred to as the “archetypal” citizen, someone who was “a male, heterosexual, able-bodied, fertile, white-collar worker.”10 Together with his sengyô shufu (fulltime housewife) counterpart the salaryman constituted the “archetypal” middle-class nuclear family that “was idealized as the bedrock of national prosperity in the postwar years.”11 Importantly this discourse of the salaryman/sengyô shufu-centered family was embedded within both postwar corporate ideology, and the socio-political and economic ideology of the postwar Japanese state, specifically the “Japan Inc.” partnership between the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, private industry, and the bureaucracy.

However, the bursting of the Bubble Economy in the early-1990s, and the prolonged post-Bubble recession has had major implications for this discourse of masculinity. The major corporate restructurings and shifts within the employment sector since the mid-1990s has called into question many of the assumptions upon which the salaryman/fulltime housewife-centered ideology, and by extension the gendered ideology of the postwar Japanese nation-state was based. In particular the abandonment of institutions such as guaranteed lifetime employment (both ideologically and in reality) and the move to a more “Western,” individualistic, economic-rationalist model of corporate culture, has had significant implications for the discourse of masculinity embodied in the salaryman. In the process, older expectations have given way to a new set of ideals and attributes, that appear to draw on a different set of more globalized neoliberal assumptions.

Yet, ironically, the reality in the second decade of the twenty-first century is that the salaryman continues to be pivotal to the ways in which Japanese corporate culture, Japanese masculinity, and indeed Japanese national identity continue to be imagined and framed. Evidence of this is the salaryman’s continuing visibility in popular culture spaces as varied as advertising, television dramas, and manga. Even within the context of corporate culture, despite the media hype about the salaryman being an anachronism from the past, research evidence seems to point to, if anything, important continuities with the past in terms of core expectations of the ideology underpinning the discourse.12 Quite clearly then, there seem to be contradictory pressures and pulls at work in relation to discourses about the salaryman in contemporary Japan. On the one hand, what it means to be a salaryman in twenty first century Japan is seemingly quite different to what being a salaryman might have meant twenty, thirty or fifty years ago. At the same time, it would appear that certain underpinnings and assumptions continue to inform and underpin the discourse surrounding the salaryman.13

Thus, with the above in mind, this paper traces the emergence of the discourse of the salaryman in the first decades of the twentieth century, during the late-Taishô/early-Shôwa period, its entrenchment in the post-World War Two (postwar) decades as the culturally idealized (but at the same time problematized and parodied) hegemonic blueprint for Japanese masculinity, and its apparent subsequent fragmentation since the collapse of the 1980s “Bubble” economy, and the ensuing two decades of economic slowdown foregrounded against considerable socio-cultural shifts. At the heart of my discussion, is the contention that salaryman masculinity, even in its apparent heyday in the 1960s and 1970s, was in a constant process of “crafting” and engagement, and was often characterized by ambivalence, contradiction and even anxiety – something that was best captured and given expression in spaces of popular and visual culture. Second, I suggest that Japan’s socio-economic and cultural trajectory from the early years of industrialization through to the post-industrial conditions of the late-twentieth/early-twenty first centuries, may be “read” through the salaryman, and specifically through the salaryman in visual culture.

Accordingly, after tracing the contours of the salaryman discourse over the Shôwa and post-Shôwa years, the paper focuses on this presence in visual culture over this span of over eight decades. Specifically, my discussion will spot-light two particular film texts book-ending the time period, one from the 1930s, the other from the 2000s – the world renowned film-maker Ozu Yasujirô’s 1932 silent classic I Was Born, But... (Umarete wa Mita Keredo) and Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s 2008 film Tokyo Sonata. Both films, as we will see, despite being separated by almost eighty years, give expression to some of the anxieties and fault lines in the everyday engagements and negotiations between salaryman subjectivities and the conditions of modernity and late-modernity, and in that regard, provide a useful lens through which to reflect on twentieth and twenty-first century Japan.

The Gendered Modernizing Nation-State and the Emergence of the Salaryman

As alluded to above, the discourse of the salaryman was situated within a specifically gendered ideology of family, nation, and citizenship, which had underpinned Japan’s path to capitalist modernity from as early as the establishment of the modernizing Meiji state in the late-nineteenth century.14 Within the framework of this ideology femininity was equated with, and defined through, the private household sphere, as exemplified in the Meiji period discourse of ryôsai kenbo (Good Wife, Wise Mother).15 Conversely masculinity, while linked to authority as a father within the family, was nevertheless firmly located within the public sphere – the prewar Japanese Empire needed pliant, productive workers and soldiers for its industrial-capitalist and military-nationalist project.16

In this regard the emergent shapings of a discourse around salaryman was inseparable from discourses about the nation and modernity in these years.17 The origins, as suggested above, may actually be traced back to the initial decades of Japan’s industrialization enterprise in the latter decades of the nineteenth century. The term “salaryman” (sarariiman) itself appears to have been coined and popularized in the years following World War One.18 However, its antecedents can be traced back to the gekkyû-tori (monthly salary recipient) of the early Meiji decades, and even the koshi-ben, a somewhat demeaning term for low-ranking samurai bureaucrats in the late Tokugawa years, who had been reduced to dangling a lunch-box (bentô) instead of a sword from their waists (koshi).19

These earlier articulations, in a sense, led to the early shapings of a distinct discourse around the salaryman from the 1920s (specifically during the late-Taishô and early-Shôwa years). It was also during these years that the salaryman really started taking shape as a distinct form of masculinity, linked with the conditions of urban, capitalist modernity, and importantly, with anxieties about this emerging modernity. To his supporters, the salaryman was the embodiment of a new, modern, industrialized, urban Japan, and to his detractors all that was wrong with this new urban middle-class, modern culture. This period of Japanese history witnessed the surfacing of the varied tensions and contradictions of modernity, as divergent discourses of ‘Japanese-ness’ (and the intertwining with gender) competed in a socio-economic climate characterized by growing inequality, tension, and flux. For many of these circulating discourses – both celebratory and anxious – the reference point was modernity, and the implications were for Japan’s future.20

The emergence and circulation, both in the scholarly and popular-press, of various discourses related to the figure of the salaryman, albeit couched more in terms of social class or lifestyle, rather than with reference to the salaryman’s masculinity, was set against this backdrop of articulations on conditions of modernity. The academic literature – reflecting the growing influence of Marxist theory – often tried to fit the salaryman within the framework of social class or in terms of lifestyle analysis (for instance social commentator Ôya Sôichi’s analysis of the salaryman and his lifestyle21), or literary critic Aono Suekichi’s 1930 Sarariiman no Kyôfu Jidai (The Salaryman’s Panic Times) which, in the words of Harootunian sought to “analyze formally the social structure of the salaryman class (Japan’s petit bourgeoisie) within the larger context of capitalist social relations in order to explain how and why they were fated to a life of continual unhappiness and psychological depression caused by the growing disparity between their consumerist aspirations and their incapacity to satisfy them.”22

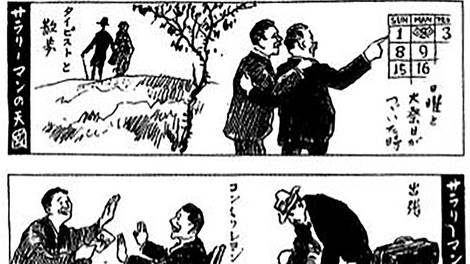

The salaryman also started being represented in spaces of popular culture, such as Maeda Hajime’s popular 1928 novel (and subsequent sequel) Sarariiman Monogatari (Story of the Salaryman), and cartoonist Kitazawa Rakuten’s popular manga depicting “sarariiman no tengoku” (Salaryman’s Heaven) and “sarariiman no jigoku” (Salaryman’s Hell).23 “Salaryman’s Hell” consisted of such things as commuting on “jam-packed” trams at peak hour, being gossiped about by colleagues, and having to work late at the end of the financial month; “Salaryman’s Heaven” included business trips, a walk with the attractive typist, and long weekends. Similarly, magazines targeting an urban, white-collar readership like Kingu (King) or the monthly Sarariiman revolved around the daily concerns of a salaryman’s life. Sarariiman, for instance contained features on a range of concerns from the economy and issues to do with the workplace, right through to pieces on aspects of “modern” life, everything from cafés through tips about fashion to advice about relationships.24 Even the newly emerging medium of film engaged with the salaryman and his lifestyle – some of the early works of Ozu Yasujirô such as Umarete wa Mita keredo... (I Was Born, But...) and Tokyo no Kôrasu (Tokyo Chorus) had the salaryman at the center of their narratives- a topic I will return to further on in this paper. Significantly, this visibility in public culture underscores the positioning of the discourse of the salaryman within the expanding conditions of capitalist modernity in 1920s/early-1930s Japan.

However, it was really in the postwar decades that the salaryman and the salaryman-centered nuclear family became the hegemonic blueprint, both for discourses of Japanese masculinity, and of the family. Japan’s defeat in the war, and the accelerated industrialization and urbanization meant that alternative/competing discourses of masculinity from the prewar decades, such as the soldier or the farmer, became less socio-culturally relevant. Rather as the white-collar sector of the economy burgeoned, with close to 40 percent of new school graduates entering into white-collar work by 1970,25 the salaryman and the associated discourse of masculinity became the overarching signifier of Japanese masculinity. At the same time, rapid urbanization, working in tandem with changes in employment structure and improvements in living standards, meant that the middle-class urban/suburban nuclear family increasingly became the norm – by 1970, 64 percent of households were in nuclear-family situations.26 Furthermore, the distancing of homes from workplaces as a consequence of urbanization and rising land prices, worked to reinforce the gender role divide within the household between the daikokubashira (quite literally, the central supporting pillar/mainstay of the house/household) husband, who was absent from home for most of the day, and the stay-at-home wife (the sengyô shufu), whose role was increasingly constructed around being a wife, and especially, mother.

Behind the standardization of the salaryman/sengyô shufu in the national psyche in the postwar period were demographic forces coalescing around the postwar “Baby Boom” generation (the dankai sedai), those born in the immediate postwar years.27 As this generation came of age, and entered the workforce, Japan was at the high-point of its “Economic Miracle” years. Companies were expanding, and the expectation was that the economy would keep growing. Consequently features of the employment system that in the prewar period had been limited to large-scale organizations, diffused out across a wider spectrum of firms, and came to signify Japanese corporate/organizational culture. These included such “pillars” of the employment system as lifetime employment guarantee, a salary and promotions system skewed towards seniority rather than performance, an emphasis on generalist, rather than specific, skills, and an overall framework of corporate paternalism.28 As the men of the baby boom generation entered into the workforce, there was an overall expectation that by the time they reached middle-age, there would be sufficient middle-management posts to absorb them.

It was this generation of baby boomers, who together with the preceding generation, the Shôwa hitoketa (those born in the first decade of Shôwa, 1926–1934), who became the foot soldiers of the “Japan Inc.” partnership between the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), big business, and bureaucracy which powered the “Economic Miracle” over the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Furthermore, the interweaving between the gender ideology foregrounding the salaryman/sengyô shufu discourse, the success of the Japanese economy over these years, and the ideology of the state needs to highlighted. In the prewar period, Japan’s project of modernity had hinged as much on an expansionist foreign policy dependent on a strong military, as on domestic industrialization and nation-building. However, following Japan’s defeat in 1945, under the new political system put into place during the Allied occupation, the military as a hegemonic ideal of masculinity was effectively neutralized. Rather, in many respects, it was the “corporate soldiers” (the kigyô senshi) of Japan Inc. who increasingly started to take on this role – even the terminology associated with the salaryman during these decades, such terms as messhi hôkô (selfless advance), senpei (advance guard), and shijô senryaku (market strategy), underscored this association.29 Moreover, the clearly demarcated separation between the paid labor of the daikokubashira husband in the public-sphere and the unpaid labor of the sengyô shufu wife within the household, allowed these “corporate warriors” to channel their time and energy (and to a large extent, their identity) into the public work sphere, thus contributing to the state’s objective of economic strength. 30

Additionally, the striving for, and achievement of, economic success as a state ideological priority was further facilitated both by the restriction on military expenditure in the postwar Allied-imposed “Peace Constitution” and by Japan’s position in the Cold War global order. With the defense of the Japanese state (and by extension, its foreign policy) now the responsibility of the United States, resources which otherwise may have been channeled into defense, could be utilized for economic recovery and growth.31 Thus, it is important to recognize the nexus between Japan’s position within the US defense and foreign policy umbrella and the success of the “Japan Inc.” framework, as being the crucible for the emergence of the salaryman/sengyô shufu as the hegemonic blueprint of family over the crucial decades of the 1950s until the 1980s.

The Fragmentation of the Salaryman Discourse and the Shifting Contours of Hegemonic Masculinity

It was within the context of the social, economic, and historical framework outlined in the previous sections, that the salaryman became the “ideal citizen” in the first two decades of the postwar period. He emerged as both the corporate “ideal” and the masculine “ideal,” shaped by, and embodying the hegemonic discourse of masculinity. Typically, he would be middle-class and often university-educated, entering the organization upon graduation from university in his early twenties. Once within the organization, he would be expected to display qualities of loyalty, diligence, dedication, and self-sacrifice. Everything about the salaryman embodied these values: his behavior, deportment (white shirt, dark business suit, lack of ‘flashy’ clothing and accessories, neat hair-style), consumer habits (for example, reading certain types of magazines), even his verbal and body language. Moreover, his success (or lack of it) would be premised not only on workplace conduct, but also on his ability to conform to the requirements of the hegemonic discourse – to marry at an age deemed suitable, and once married to perform the appropriate gender role befitting the role of husband/provider/father. This type of “Everyman” kaisha ningen and/or kigyô senshi hero figure figured prominently in spaces of popular culture. This included contemporary film such as the Tôhô Film company’s Shachô (President) series of the 1960s, some of Ozu’s postwar works like the 1956 Sôshun (Early Spring), or the 1960 suspense drama Kuroi Gashû: Aru Sarariiman no Shôgen (The Black Album: The Testimony of a Salaryman) based on one of the works of crime fiction writer Matsumoto Seichi. As with the prewar period, these representations also extended to the innumerable business novels (kigyô shôsetsu), magazines and salaryman manga of the period.32

However, even at the height of the “glory days” of the Economic Miracle, the figure of the daikokubashira salaryman, and the discourse of masculinity built up around him, was not as monolithic and unified as might appear at initial glance. First, as indicated earlier, even at the high-point of the Japan Inc. system in the 1970s, only a minority of the male workforce would have fallen within the strictest definitional parameters of the salaryman.33 This meant that the hegemonic hold of the salaryman discourse notwithstanding, there were large swathes of the male population who were outside its orbit. Thus side-by-side with the salaryman discourse, were other masculinities, co-existing and intersecting with it. Examples included the discourse of masculinity and gender embodied in the student activists of the 1960s, or the “anti-hero” cinema masculinity of actors like Takakura Ken and Ishihara Yûjiro or even the bumbling, ineffectual but endearing character of Tora-san (played by actor Atsumi Kiyoshi) in the enormously popular Otoko wa tsurai yo (It’s Tough Being a Man) series of films.

Second, the discourse of the salaryman itself, even in its heyday, was not free from contestation and interrogation. While at one level the salaryman may have been projected as the “archetypal” citizen, at another level, there was a degree of ambivalence and critique about the costs of salaryman masculinity to himself, his family, and society in general. These ranged from humorous, but nevertheless critical portrayals of the salaryman and his lifestyle in popular culture spaces, such as in the 1970s manga Dame Oyaji (Useless Dad), to growing public discourse about the loss of authority of the father within the household, the so-called “absent father syndrome.”34 Such negative readings of the salaryman and his lifestyle further intensified during the “bubble” economy boom years of the 1980s, when the media focused on phenomena like karôshi (sudden death caused by work-related conditions), kitaku-kyohi (fear of going home, due to lack of communication between the salaryman and his family), and tanshin funin (employees forced to live away from their families for extended periods of time due to job transfers).35

Nevertheless, notwithstanding the above critiques, it was really only after the collapse of the Bubble Economy boom in the early-1990s and the subsequent economic stagnation through the “Lost Decade” of the 1990s and the 2000s that the salaryman/sengyô shufu based family discourse started being challenged in an innate sense. Prior to the 1990s, the perception seemed to be that despite modifications to the external contours of the discourse, the salaryman and all that he signified would remain a fixture on the psycho-cultural landscape of Japan. The post-Bubble recession and the ongoing socio-economic upheavals and shifts had a significant impact on this perception (and reality). In contrast to the corporate prosperity and close to full-employment conditions of the 1980s, the 1990s saw a dramatic turnaround in the economic climate. The decade was characterized by a succession of corporate bankruptcies, as well as rising unemployment, as organizations sought to cut costs and restructure. As a consequence the official unemployment rate that had been 2.1 percent in 1992, rose to 4.7 by the end of the decade, and up to 5 percent by 2001.36

Two demographics were particularly hard-hit: youth (especially young female graduates), and middle-aged men.37 As companies drastically reduced their intake of new recruits in what came to be dubbed the “Employment Ice Age,” increasing numbers of younger Japanese sought work in the casual/temporary freeter (furîtâ) sector of the economy, with the number of part-time/temporary workers under 35 years of age reaching over 2 million by 2004.38 While for some, this may have been a deliberate choice, due to the relative flexibility of the freeter sector, for growing numbers this became the only available long-term source of paid work.39

The other group particularly hard hit were middle-aged male corporate employees. As mentioned above, this cohort had entered the workforce at a time when companies were expanding, with the general expectation being that this would continue as they moved up the ranks into middle-management. However, in the context of the abrupt downturn of the 1990s, corporations found themselves with a costly layer of fat around the middle. The very men who had previously embodied the archetypal citizen – middle-class, middle-aged, middle-management husbands and fathers – were now equated with a lack of efficiency, and increasingly seen as a burden. In the increasingly globalized economic rationalist environment of the post-Bubble era, the priority shifted from the earlier emphasis on managers with non-specific generalist skills nurtured over the long-term, to individuals possessing very specific skills who would be of immediate measurable benefit to the organization. The new corporate ideal was no longer the kigyô senshi type salaryman of the pre-1990s. Rather in the new domestic and global economic reality it was a new generation of more individualistic, entrepreneurial corporate executives who started being projected as the new hegemonic ideal – in the context of the harsher, globalized, neoliberal realities of (both private and public sector) organizational culture, idealized (and expected) attributes and behavior no longer focused around “hard work (kinben), perseverance (nintai) and group harmony (kyôchôsei)” but rather around “entrepreneurial spirit (kigyôka seishin), competitive society (kyôsô shakai), and self-responsibility (jikosekinin).”40

As even large elite organizations started abandoning institutions like lifetime employment, unemployment among middle-aged males became an issue – the jobless rate for men in the 45-54 age group, which had been a low 1.1 percent in 1991, climbed to 4.3 percent by 2002; for men in the 55-64 cohort the rate in 2002 was 7.1 percent.41 For many middle-aged salarymen who had entered the workforce expecting to be with the same employer until retirement, the implications of being retrenched were particularly acute. Not only did these men have to contend with the financial strain of being laid-off, but also given the centrality of the daikokubashira husband/father identity in their lives, their very masculinity, within society, and more specifically, within the family, was compromised. Hence, for many, there was a sense of betrayal by the very corporations to whom they had devoted their whole careers, and a deepening sense of anxiety about their place in society. In many respects this was an anxiety about the emasculation of previously under-problematized power and authority- one possible fallout being, for instance, a marked increase in the male suicide rate particularly among middle-aged men. 42

More than two decades on from the bursting of the Bubble Economy boom, this (apparent) unraveling of many of the givens of salaryman masculinity appears to have continued. At one level, given all the upheavals, particularly within the labor market and corporate sector, of the past two decades, it would make sense to dismiss the salaryman, and the discourse of masculinity he embodied, as an anachronistic vestige of a past era. Public imaginings of Japanese masculinity in the 2000s started to be increasingly dominated by tropes such as the otaku/techno-geek, the freeter, the male escorts (hosuto) of “Host Clubs,” or the seemingly asexual/feminized sôshokukei danshi (“Herbivorous Men”) of the mid-2000s, or even the outwardly relatively conventional, but nevertheless interrogating (of expectations of traditional gender roles) ikumen, men who define their identity through active childcare, rather than work.43 All of these discourses (indeed, practices) of masculinity come across as complete antitheses of the salaryman, and may well appear to be displacing him in a struggle for a new hegemonic masculinity. Indeed, these shifts may be indicative of what Sabine Frühstück and Anne Walthall, writing, at the start of the second decade of the twenty-first century, refer to “numerous microcosms of ‘(hegemonic) masculinities’” (my italics).44

However, we need to be careful about reading too much into practices/styles (rather than discourses/ideologies) of sub-cultural masculinities like the otaku or sôshokukei danshi, whose socio-cultural impact often gets disproportionately magnified as a result of media commodification. Rather, what we need to consider when reflecting on articulations of masculinities in the context of post-Bubble Japan, is the extent to which core assumptions about socio-culturally hegemonic expectations of masculinity are, or, are not, being dislodged. In particular, we need to contemplate whether the ostensibly consumption-mediated, seemingly "anti-salaryman" masculinities like the otaku or sôshokukei danshi, or even the ikumen are really dismantling the work/production/masculinity nexus.

In fact, despite all the socio-economic and corporate culture upheavals and shifts over the post-Bubble era, the discourse of the salaryman has continued to be remarkably tenacious. This comes through in the persistent presence of the salaryman in the popular cultural landscape of twenty-first century Japan – for instance, the ongoing popularity of salaryman manga icons like Sarariiman Kintarô and Shima Kôsaku, or the fact that in the mid/late-2000s one of the most popular shows on NHK was the comedy/parody series (and subsequent movie) Sarariiman Neo, or the success of the J-Pop/hip-hop group Ketsumeishi’s 2010 single Tatakae! Sarariiman (Fight On! Salaryman), or even the continuing profile of the business novel as a popular literary genre. Moreover, paradoxically, the ongoing economic slowdown and harsh labor market conditions of the past two decades have actually worked to enhance the socio-cultural appeal of salaryman masculinity. At first glance, this may come across as counter-intuitive. However, in reality the post-Bubble years have seen a widening divide, in terms of financial security and socio-cultural status, between those male graduates able (or lucky enough) to enter into the parameters of salaryman masculinity, and those (in increasing numbers) who find themselves relegated to low-paying, insecure jobs in the non-permanent sector.

This has ramifications for such considerations as the ability to attract potential marriage partners, start a family, get a bank loan to purchase a house, pay childcare costs, etc. – essentially access to all the discursive and ideological markers of “middle-class” respectability. Despite the not insignificant shifts in attitudes towards gender, sexuality, and family over the past two decades, the notion of the husband being the primary household provider (essentially, the daikokubashira) remains stubbornly entrenched, as reflected in the much higher rates of singlehood among men in non-permanent work.45 While young women today are much less likely than their mothers’ generation to be sengyô shufu (fulltime housewives), there is still a continuing desire to marry a man with job and income stability.46

Thus, the discourse of the salaryman, may well, in some respects, be returning to the socio-culturally idealized elite status it occupied in the late-1950s and 1960s, when access into “salaryman-ness” (through university education, for instance) translated through to an economic and financial security (and consequently socio-cultural status) not available to men who may have only had a junior-high or high school education. In the post-Bubble era, this finds echoes in the divide between the growing population of men restricted to unstable, irregular contract or freeter work (the precariat), and those able, or lucky enough to enter into the domain of fulltime, permanent work, with all the social, financial, and economic dividends that go with the status. However, at the same time, there is absolutely no denying that the on-the-ground reality of being a salaryman in neoliberal, economically downbeat 2010s Japan, is quite different from what being a salaryman entailed in the economically buoyant 1960s, '70s, '80s, and even into the '90s.

As noted in the introduction to this paper, since the 1990s there has been a shift to the privileging of a newer form of idealized corporate masculinity, referencing a more Euro-American-influenced neoliberal and global hypermasculinity. This is a “style” of masculinity that, in contrast to the company-centered articulations of past salaryman attributes, is marked by “increasing egocentrism, very conditional loyalties (even to the corporation), and a declining sense of responsibility for others.”47 Significantly, this is a style of corporate masculinity/corporate ideology that is seen, in some quarters, as providing the key to resuscitating Japan’s sluggish economy, and reinvigorating its creative potential. In some respects, this newer form of salaryman/corporate masculinity may well come across as more "liberating", in the sense of opening spaces for expression of individuality and flexibility. For instance, in relation to gender in the context of corporate culture, the newer shapings of corporate masculinity may come across as less patriarchal and gender exclusivist.

The reality, though, is more complex. Indeed, in the harsher, more efficiency-driven post-Bubble organizational culture, if anything, the qualities and attributes defining “success” in the workplace, rather than being “gender neutral” have become even more starkly masculine in many respects.48 While the form of salaryman masculinity may have altered in response the pressures and contestations, the core ideological assumptions at the heart of the discourse, such as the work/masculinity nexus and the expectations of the man as heterosexual reproducer, have not altered significantly. In this respect, despite the fact that the Japan of early-Shôwa 1920s/1930s Japan, and the Japan of contemporary post- Shôwa 2000s and 2010s, are vastly different in so many regards, when it comes to some of the core assumptions about masculinity perhaps not that much has changed.

Visual Culture Articulations of the Salaryman Over the Shôwa and Post-Shôwa Years

As suggested in the previous section, when it comes to the salaryman, and his discursive framings, there is continuity over the entire Shôwa period, and into the post-Shôwa years. This comes across, for instance, in visual culture references to the salaryman over this span of eight or nine decades. Thus, many of the concerns and even tongue-in-cheek parodies of the salaryman in Kitazawa Rakuten’s Sarariiman no tengoku and jigoku referred to earlier in this paper, find echoes decades later in texts like the 1970s manga Dame Oyaji, or the more recent parodies like Sarariiman Neo or, more recently the single-frame manga, created by comedian Tanaka Hikaru, Sarariiman Yamasaki Shigeru, which has been popular on social media platforms including Twitter and Instagram.49 Similarly, film texts spanning the Shôwa and post-Shôwa years also convey a sense of some of the continuities in relation to the calibrations and expressions of salaryman masculinity. For instance, some of the issues and anxieties of salaryman life in the early 1930s silent-film works of Ozu including Tokyo Chorus (Tokyo no Kôrasu) and I Was Born, But... (Umarete wa Mita Keredo), recur in early postwar films like Ozu’s Early Spring (Sôshun 1956) and Kurosawa Akira’s 1952 To Live (Ikiru); in later postwar works like Morita Yoshimitsu’s Family Game (Kazoku Gêmu, 1983), Suo Masaaki’s 1996 Shall We Dance (subsequently adapted into a Hollywood version with the same name); through to post-Bubble era works like Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Tokyo Sonata (2008) and the 2010 film, Railways: The Story of a 49-year Old Man Who Became a Train Driver (Reiruuezu: 49-sai de Densha no Untenshu ni Natta Otoko no Monogatari). At the same time, these films provide us with periodic visual snapshots of differing moments in the narrative of Japan’s modernity and late-modernity over the Shôwa and post-Shôwa years.

Bookending Shôwa and Post-Shôwa Through Salaryman Anxieties

Following on from the above, by way of bookending the time period at the heart of the discussion in this paper, the Shôwa and post-Shôwa years, I will spotlight two specific films from either end of the time-frame – Ozu Yasujirô’s I Was Born, But... from 1932, and Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s 2008 Tokyo Sonata. Both are set against quite different socio-historical and economic conditions. I Was Born, But... was situated in the era following 1923's Great Kanto Earthquake, in the context of an expanding urban modernity and the emergent visibility of a new white-collar-based, middle-class masculinity. At the same time, the film took place against the backdrop of growing inequalities and contradictions – of class, of rural/urban, traditional/modern, of nostalgia for the past/yearning for the future. Significantly, these inequalities, which Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano refers to as the “split nature of Japanese modernity” were linked to the shift from the “Taishô Democracy” years of the 1910s and 1920s to the growing domination of the military in politics, and the slide towards authoritarianism through the 1930s.50 Tokyo Sonata, on the other hand, is set against the backdrop of the mid-2000s, when the dismantling and unraveling of many of the social, economic, and even cultural institutions and fallback networks of the postwar “Japan Inc.” decades, were becoming an entrenched reality.

On the surface, the two films appear to draw on quite different cinematic genre, and are directed by two (apparently) very different filmmakers. Ozu, is most strongly associated with his body of aesthetically delicate, understated and introspective postwar social realist classics like Late Spring (Banshun1949), Tokyo Story (Tôkyô Monogatari, 1953), Floating Weeds (Ukigusa 1959), and An Autumn Afternoon (Sanma no Aji, 1962). I Was Born, But... is an example of Ozu’s early silent-film era works, situated within the body of film from the early-1930s known as shôshomin eiga (middle-class cinema) characterized by the weaving together of light-hearted comedy, humanism, and engagement with the everyday concerns of the emerging urban middle-classes.51

Kurosawa Kiyoshi, the director of the 2008 Tokyo Sonata, on the other hand, is better known as a maker of innovative horror/suspense cult films, such as Cure (1997), Pulse (2001) and more recently the award-winning Seventh Code (2013).52 Tokyo Sonata, however, while incorporating some influence from his earlier horror/thriller works, is more reminiscent, in terms of narrative and style, both of works like Morita Yoshimitsu’s The Family Game (Kazuko gêmu. -1983) with its playful/fantastical aspects,53 as well as some of Ozu’s social realist salaryman/family-centered films (as indeed, flagged in the title of the film, Tokyo Sonata, which is reminiscent of Ozu’s 1953 Tokyo Story).

However, as already hinted at, the two films despite their apparent temporal and contextual distance, do in fact have crossovers that make them useful texts through which to reflect on both the underpinnings and the fragilities of salaryman masculinity over the decades in question. I Was Born, But... is situated at a historical moment when the discourse of the salaryman was starting to take shape and subsequently emerge, in the postwar years, as the culturally privileged hegemonic blueprint for Japanese masculinity. Tokyo Sonata, on the other hand, references a historical moment when the discourse of salaryman masculinity (or at least, its entrenched socio-cultural presence) appeared to be fragmenting and weakening. Yet, both texts engage with and give expression to very similar anxieties about one of the core underpinnings of salaryman masculinity – the link between successfully (or not) living up to the cultural ideal of the husband/father daikokubashira provider.

I have discussed Tokyo Sonata in greater depth elsewhere.54 Hence, for the purposes of this paper, after providing brief overview of the narratives of Tokyo Sonata and I Was Born, But... , I focus on two specific scenes in both texts that capture the sense of masculine instability at the core of hegemonic masculinity. The narrative of Tokyo Sonata revolves around the impact of corporate re-structuring on a seemingly conventional middle-class family (goku futsû kazoku), with a salaryman father, a sengyô shufu mother, and two sons, living in the anywhere/everywhere landscape of suburban Japan. The father, Sasaki Ryûhei, initially comes across as something of a “poster boy” for Japan Inc. era salaryman masculinity – a forty-six year old middle-management kachô (section manager) in a large organization. Ryûhei’s seemingly predictable middle-class salaryman life is abruptly shattered when, as a result of organizational out-sourcing to China, he is suddenly laid off, a victim of the coldly efficient economic rationalist realities of post-Bubble Japan. The film is a very powerful study of the impact of the change in circumstances on Ryûhei and on the rest of his family.

I Was Born, But... similarly revolves around a middle-class salaryman, Yoshii Ken’nosuke, and his family, and, as with Tokyo Sonata, the salaryman father’s efforts to successfully live up to the expectations of being a daikokubashira husband and father. Just as Tokyo Sonata was situated against a socio-cultural landscape of corporate downsizings and unemployed salarymen, the socio-economic backdrop to I Was Born, But... was also a time of similar anxiety and uncertainty for the salaryman; for instance, in the year the film was released (1932), one in five of all unemployed workers was a middle-class white-collar male.55 As with the Sasaki family at the start of Tokyo Sonata, the Yoshii family also seem, at least initially, to be successfully performing the expectations of urban middle-class respectability. For instance, in order to be closer to where his department director lives, Ken’nosuke moves his family to a new aspirational middle-class suburban residential area. The film, accordingly, follows two inter-weaving narratives, that of the two Yoshii boys’ attempts to integrate into their new school and neighborhood, and that of Ken’nosuke’s relationship with his workplace and his attempts to ingratiate himself with his boss, as well as his performance of the daikokubashira patriarch at home.

The scenes in the two films I wish to focus on are moments in the narrative where this striving effort and performance of the middle-class breadwinner role crumbles in humiliating ways. In Tokyo Sonata, Ryûhei, unable to reveal his newly “unemployed” status at home, spends his days alternating between killing time at a city-center park populated by homeless down-and-outs and unemployed salarymen like himself, and visiting the official employment exchange, in search of a job commensurate with his white-collar managerial expertise. At first his efforts are in vain, but finally he does get short-listed for a white-collar management position. The scene where Ryûhei interviews for the job brings into sharp relief the contrast between the discourse of salaryman masculinity privileged when Ryûhei was being “crafted” into it (so during the Bubble years of the 1980s), and the dominant articulations of its twenty-first century counterpart. In contrast to Ryûhei’s almost frumpily old-fashioned presentation, his interviewer comes across as a fashionably groomed, slick young thirty-something embodiment of the new post-Bubble generation of salarymen discussed earlier in the paper. In language normally reserved for subordinates, the interviewer asks (the age-wise, senior) Ryûhei what specific skills or talents he can bring to the organization. Ryûhei fumbles trying to come up with anything convincing, other than the ability to sing karaoke and his long experience of maintaining smooth inter-personal relations in the workplace – well-recognized attributes of the earlier generation of generalist managers, but clearly out of sync with the requirements of the new specific-skills based workplace ideology. Ryûhei’s humiliation is sealed when his sneering younger interviewer orders him to demonstrate his karaoke skills there and then, using a pen as a proxy microphone.

In another scene in the film, Ryûhei’s continued efforts to perform the expectations of the cultural ideal of the daikokubashira husband and father looking after his family, are similarly challenged and dismantled. The elder son, Takashi, decides to enlist in the first contingent of Japanese mercenaries being recruited to support the United States military’s effort in Iraq. Takashi’s decision to enlist, seems to be his way of escaping the boredom of unstable freeter work and bleak prospects facing his generation. Ryûhei is unequivocally opposed and tries unsuccessfully to bully, then to plead with Takashi to change his mind. The scene brings to the surface, and juxtaposes, powerful societal undercurrents of anxiety about the loss of authority, and indeed, masculinity, both within the micro-space of the family, and within the macro-space of the nation-state. Takashi’s reasoning for his choice is his desire to “protect” (mamoru) his parents and his younger brother, much in the same way that the US “protects” Japan. His father’s assertion that he is responsible for looking after his family, results in his son challenging his authority to be the “protector,” and pointedly asking what it is that he does everyday. Ryûhei’s inability to respond satisfactorily reflects the cracks emerging in his efforts to maintain the façade of daikokubashira father and husband. In the end, despite not getting his parents’ explicit consent, Takashi enlists and goes to Iraq.

In I Was Born, But... the fragility of Yoshii Ken’nosuke’s authority as the daikokubashira father is similarly challenged and revealed to his two young sons. The contradiction between his behavior at home and his weak, subservient behavior in public is revealed during a screening of an amateur home movie by his buchô (department head), Iwasaki, in which Ken’nosuke (not unlike Ryûhei in the above scene from scene in Tokyo Sonata) is forced to deliberately play a ridiculous, fawning office clown. The public exposure (indeed, emasculation) of their father results in Ken’nosuke’s two boys going on a short-lived hunger-strike after angrily confronting their father about his weak, subservient behavior in public, which they see as being at odds with his insistence that the boys work hard and distinguish themselves. Significantly, almost eighty years down the track, very similar dynamics are played out in the confrontation between Ryûhei and his older son in the Tokyo Sonata scene discussed above.

In both films, despite these moments of rupture and displacement of authority, both families eventually go back to a “new” normal, with the father’s position and respect seemingly restored. The final scene in I Was Born, But... has the two Yoshii boys sitting beside the father eating the breakfast they had earlier angrily rejected. The scene suggests both a reconciliation with the reality of their father’s need to be subservient to his boss, and, a realization that in their father, the boys may well be seeing their own futures, settling into a compromise of “unresolved continuation.”56 This sense of “unresolved continuation” also plays out in the final scenes of Tokyo Sonata. Over the course of one twenty-four hour period, all three remaining members of the family- the father, Ryûhei, Megumi, the mother, and the younger son Kenji- experience a series of (indirectly) inter-connected out-of-the-ordinary, almost surreal experiences, which seem to suggest the final fragmentation of the carefully calibrated salaryman-father-centered family performance. Yet, in a scene reminiscent of the closing moments of I Was Born, But..., the morning after their various traumatizing experiences all three are shown seated around the kitchen table, sharing a meal with no apparent reference to the collective traumas undergone. The “everyday-ness” of this scene is accentuated variously through the shared family meal, the sound of a passing train in the background, and a television news report (about the Iraq War) droning on in the background. This “unresolved continuation’” is further underscored by a letter sent by Takashi, the older son, both gesturing towards a healing and reconciliation with the family, but also stating his intention to continue staying on in Iraq to help the local population, despite the disbanding of his Japanese mercenary unit.

Conclusion

As stressed in the introduction to this paper, gender, and specifically masculinity, has been an essential component of the project of nation-state building, everywhere. This applies to Japan too, and as I have suggested in this paper, Japan’s processes of modernization and nation-building from the mid-19th century right up to the present, can be considered through the crafting of the discourse of the white-collar salaryman, at the heart of which lay the equation of masculinity with the public/work sphere (and conversely “femininity” with the private/household sphere). As I outlined in the first half of the paper, the emergence of this discourse of masculinity was closely linked to Japan’s project of nation-building and industrialization. Over the postwar decades, particularly over the 1950s to the 1990s, salaryman masculinity could have been regarded as the culturally privileged hegemonic discourse of masculinity in Japan. Even in the context of the considerable socio-economic and cultural shifts since the 1990s, the salaryman, and the ideological assumptions at the heart of the discourse of masculinity he signifies, has continued to occupy an important place in the collective national imaginary. However, what I have also tried to map through this paper, particularly with reference to articulations of the discourse in visual and popular culture, is the fact that rather than being a monolithic, un-changing constant, the contours of the discourse of the salaryman (and masculinity, both hegemonic and non-hegemonic) are in a constant state of flux as it is shaped (indeed “crafted”) through dynamics of negotiation and engagement, with other (equally shifting) discourses of gender, class, and nation. This was as much the case in the early years of the discourse taking shape during the 1920s and 1930s, as in the more recent post-Shôwa years of the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. This in turn serves to remind us that, at the end of the day, hegemonic discourses – of gender, of the family, of the nation – are constantly in a process of being crafted and re-crafted.

Selected Filmography

Kurosawa, Kiyoshi, dir. Tokyo Sonata. DVD. Fortissimo Films 2008.

Ozu, Yasujirô, dir. Umarete wa mita keredo (I Was Born, But...) Shôchiku Eiga, 1932. DVD. Criterion Collection, 2007.

References

Beasley, Christine. “Rethinking Hegemonic Masculinity in a Globalizing World.” Men and Masculinities 11.1 (2008): 86–103.

Blätter, Sidona. “Identity Politics: Gender, Nation and State in Modern European Philosophy.” In Gender, Nation and State in Modern Japan, edited by Andrea Germer, Vera Mackie, and Ulrike Wöhr, 273–289. London: Routledge, 2014.

Brinton, Mary C. Women and the Economic Miracle: Gender and Work in Postwar Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Cavallaro, Dani. Critical and Cultural Theory: Thematic Variations. London: The Athlone Press, 2001.

Cole, Robert E., and Ken’ichi– Tominaga. “Japan’s Changing Occupational Structure and Its Significance.” In Japan’s Industrialization and its Social Consequences, edited by Hugh Patrick, 53–95. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.

Condry, Ian, “Love Revolution: Anime, Masculinity, and the Future.” In Recreating Japanese Men, edited by Sabine Frühstück and Anne Walthall, 262–283. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

Connell, Raewyn. The Men and the Boys. St. Leonards, NSW, Australia: Allen and Unwin, 2000.

Connell, Raewyn, and James W. Messerschmidt, “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.” Gender and Society 19.6 (2005): 829–859.

Connell, Raewyn, and Julian Wood. “Globalization and Business Masculinities.” Men and Masculinities 7.4 (2005): 347–364.

Cook, Emma E. “Intimate Expectations and Practices: Freeter Relationships and Marriage in Contemporary Japan.” Asian Anthropologist 13.1 (2014): 36–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1683478X.2014.883120

Cook, Emma E. “(Dis)Connections and Silence: Experiences of Family and Part-time Work in Japan.” Japanese Studies 36.2 (2016): 155–172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2016.1215228

––––––Reconstructing Adult Masculinities: Part-time Work in Contemporary Japan. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, 2015. [Accessed 7 October, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central].

Dales, Laura, and Emma Dalton. “Online Konkatsu and the Gendered Ideals of Marriage in Contemporary Japan.” Japanese Studies 36.1 (2016): 1–19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2016.1148556

Dasgupta, Romit. “The 1990s ‘Lost Decade’ and Shifting Masculinities in Japan.” Culture, Society and Masculinity 1.1 (2009): 69–85.

–––––– “Emotional Spaces and Places of Salaryman Anxiety in Tokyo Sonata.” Japanese Studies 31.3 (2011): 373–386.

–––––– Re-reading the Salaryman in Japan: Crafting Masculinities. London: Routledge, 2013.

–––––– “Salaryman Anxieties in Tokyo Sonata: Shifting Discourses of State, Family and Masculinity in Post-Bubble Japan.” In Gender, Nation and State in Modern Japan, edited by Andrea Germer, Vera Mackie, and Ulrike Wöhr, 255–272. London: Routledge, 2014.

Dower, John W. “Peace and Democracy in Two Systems: External Policy and Internal Conflict.” In Postwar Japan as History, edited by Andrew Gordon, 3–33. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Eagleton, Terry Ideology: An Introduction. London: Verso, 1991.

Freedman, Alisa. Tokyo in Transit: Japanese Culture on the Rails and Road. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011.

Frühstück, Sabine and Anne Walthall. “Introduction: Interrogating Men and Masculinities.” In Recreating Japanese Men, edited by– Sabine Frühstück and Anne Walthall, 1–21. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

Fujii, Harue. Nihon-gata kigyô shakai to josei rôdô: Shokugyô to katei no ryôritsu o mezashite [The Japanese Model of Industrial Society and Female Labour: Aiming for a Work/Home Balance]. Tokyo: Mineruba (Minerva) Shobô, 1995.

Gerow, Aaron. “Playing With Postmodernism: Morita Yoshimitsu’s The Family Game (1983).” In Japanese Cinema: Texts and Contexts, edited by Alaistair Phillips, and Julian Stringer, 240–252. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Germer, Andrea, Vera Mackie, and Ulrike Wöhr. “Introduction: Gender, Nation and State in Modern Japan.” In Gender, Nation and State in Modern Japan, edited by Andrea Germer, Vera Mackie, and Ulrike Wöhr, 1–24. London: Routledge, 2014.

Harootunian, Harry. Overcome by Modernity: History, Culture, and Community in Interwar Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Hazama, Hiroshi. Keizai taikoku o tsukuriageta shisô: Kôdo keizai seichô-ki no rôdô-êtosu [The Philosophy that Built-up the Economic Superpower: The Labour Ethos of the High-Speed Economic Growth Period]. Tokyo: Kôshindô, 1996.

Iwakami, Mami. “Chûkônenki no kazoku: Aratana seifuteinetto kôsaku ni mukete [Middle-aged Families: Towards Creating a New Safety Net].” In Koyô ryûdôka no naka no kazoku: Kigyô shakai, kazoku, seikatsu hoshô shisutemu [Family in a Time of Unstable Employment: Industrial Society, Family, Social Security System], Kazoku shakaigaku kenkyû shiriizu [Family Sociology Studies Series], edited by Keiko Funabashi and Michiko Miyamoto, 121–144. Kyoto: Mineruba (Minerva) Shobô, 2008.

Iwase, Akira. “Gekkyû hyaku-en” sarariiman: Senzen Nihon no “heiwa”na seikatsu [“The Hundred Yen a Month” Salaryman: The “Peaceful” Lifestyle of Prewar Japan]. Tokyo: Kôdansha, 2006.

Joo, Woojeong. “I Was Born Middle Class, but...: Ozu Yasujiro’s Shôshimin eiga in the Early 1930s.” Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema 4, 2 (2012): 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1386/jjkc.4.2.103_1

Karlin, Jason G. “The Gender of Nationalism: Competing Masculinities in Meiji Japan.” The Journal of Japanese Studies 28.1(2002): 41–77.

Kelly, William W. “Finding a Place in Metropolitan Japan: Ideologies, Institutions, and Everyday Life.” In Postwar Japan as History, edited by Andrew Gordon, 189–216. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Kinmonth, Earl H. The Self-Made Man in Meiji Japanese Thought: From Samurai to Salaryman. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981.

Kitazawa Rakuten Kenshô Kai (Kitazawa Rakuten Memorial Association) ed. Rakuten manga-shû taisei: Taishô-hen (Compilation of Collected Rakuten Manga: Taishô Collection). Tokyo: Gurafikku-sha, 1973.

Kodama, Ryôko. “Chichioya-ron no genzai: Nana-jû nendai ikô o chûshin toshite [Contemporary Fatherhood Debates: Focusing on the Seventies Onwards].” In Nihon no otoko wa doko kara kite, doko e iku no ka: Dansei sekushuariti keisei (Kyôdô kenkyûkai) [Where Have Japanese Men Come From, Where Are They Going?: Construction of Male Sexuality (Collaborative Research)], edited by Haruo Asai, Satoru Ito, and Yukihiro Murakami, 122–149. Tokyo: Jûgatsusha, 2001.

Koyama, Shizuko [trans Vera Mackie]. “Domestic Roles and the Incorporation of Women into the Nation-State: The Emergence and Development of the ‘Good Wife, Wise Mother’ Ideology.” In Gender, Nation and State in Modern Japan, edited by Andrea Germer, Vera Mackie, and Ulrike Wöhr, 85–100. London: Routledge, 2014.

Lambert, Priscilla A. “The Political Economy of Postwar Family Policy in Japan: Economic Imperatives and Electoral Incentives.” The Journal of Japanese Studies 33.1 (2007): 1–28.

Mackie, Vera. “Embodiment, Citizenship and Social Policy in Contemporary Japan.” In Family and Social Policy in Japan: Anthropological Approaches, edited by Roger Goodman. 200–229. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

–––––– Feminism in Modern Japan: Citizenship, Embodiment and Sexuality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Maeda, Hajime. Sarariiman monogatari (Tales of the Salaryman). Tokyo: Tôyô Keizai Shinpôsha, 1928.

Matanle, Peter. “Beyond Lifetime Employment? Re-fabricating Japan’s Employment Culture.” In Perspectives on Work, Employment and Society in Japan, edited by Peter Matanale and Wim Lunsing, 58–78. Houndmills and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

McDonald, Keiko I. Reading a Japanese Film: Cinema in Context. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2006.

Messerschmidt, James W. “Engendering Gendered Knowledge: Assessing the Academic Appropriation of Hegemonic Masculinity.” Men and Masculinities 15.1 (2012): 56–76.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. White Paper on the Labour Economy 2005. Accessed October 15, 2016. www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/l-economy/

Mizukoshi, Kosuke, Florian Kohlbacher, and Christoph Schimkowsky. “Japan’s Ikumen Discourse: Macro and Micro Perspectives on Modern Fatherhood.” Japan Forum 28.2 (2015): 212–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2015.1099558

Molony, Barbara, and Kathleen Uno. “Introduction.” In Gendering Modern Japanese History, edited by Barbara Molony and Kathleen Uno, 1–35. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Asia Center/Harvard University Press, 2005.

Nakatani, Ayami. “The Emergence of ‘Nurturing Fathers’: Discourses and Practices of Fatherhood in Contemporary Japan.” In The Changing Japanese Family, edited by Marcus Rebick and Ayumi Takenaka, 94–108. London: Routledge, 2006.

Ôya, Sôichi. Ôya Sôichi zenshû (Collected Works of Ôya Sôichi) (vol. 2). Tokyo: Sôyôsha,1981.

Phillips, Alastair, and Julian Stringer. “Introduction.” In Japanese Cinema: Texts and Contexts, edited by Alaistair Phillips and Julian Stringer, 1–24. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Phillips, Alastair. “The Salaryman’s Panic Time: Ozu Yasujirô’s I Was Born, But… (1932).” In Japanese Cinema: Texts and Contexts, edited by Alaistair Phillips and Julian Stringer, 25–35. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Roberson, James E. Japanese Working Class Lives: An Ethnographic Study of Factory Workers. London: Routledge, 1998.

Sataka, Makoto. Keizai shôsetsu no yomikata: Keizai shôsetsu ga kaita Nihon no kigyô (How to Read Business Novels: Japanese Firms as Depicted in Business Novels). Tokyo: Tokuma Bunko, 1991.

Satô, Hiroshi, and Atsushi Satô. Shigoto no shakaigaku: Henbôsuru hataraki-kata (The Sociology of Work: Changing Patterns of Work). Tokyo: Yûhi Books, 2004.

Silverberg, Miriam. “Constructing the Japanese Ethnography of Modernity.” Journal of Asian Studies 51.1 (1992): 30–54.

Taga, Futoshi. “Tsukurareta otoko no raifusaikuru [The Constructed Life-cycle of Men].” In ‘Otokorashia’ no gendaishi [The Contemporary History of ‘Manliness/Maleness], edited by Tsunehisa Abe, Sumio Obinata, and Masako Amano, 158–190. Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Hyôron-sha, 2006.

–––––– “Kojin-ka shakai ni okeru ‘otokorashisa’ no yukue: Sarariiman no ima-tokore kara (The Future Direction of ‘Masculinity/Manliness’ in an Individualized Society: From the Salaryman’s Present Position).” In Yuragu sarariiman seikatsu: Shigoto to katei no hazama de (Unstable Salaryman Life: Between Work and Family), edited by Futoshi Taga, Futoshi, 187–217. Tokyo: Minerva Shobô, 2011.

Takeyama, Akiko. “Intimacy for Sale: Entrepreneurship and Commodity Self in Japan’s Neoliberal Situation.” Japanese Studies 30.2 (2010): 231–246.

Tanaka, Hidetomi, and Muneyoshi Nakamura. “Wasurerareta keizai-shi ‘Sarariiman’ to Hasegawa Kunio (Hasegawa Kunio and the Forgotten Business Journal ‘Sarariiman’ [‘The Salaryman’]).” Festschrift for the 30th Anniversary of Jôbu University, Joint Publication of the Department of Commercial Science 10.2 (1999), and Department of Management and Information Science 20 (1999), Jôbu University: 1–22.

Tao, Masao. Kigyô shôsetsu ni manabu soshiki-ron nyûmon (An Introduction to Studying Organizational Theory in Business Novels). Tokyo: Yûhikaku Sensho, 1996.

Ueno, Chizuko. “Kigyô senshitachi [Corporate Warriors].” In Danseigaku: Nihon no feminizumu bessatsu [Men’s Studies: Special Edition of Japanese Feminism], edited by Teruko Inoue, Chizuko Ueno, and Yumiko Ehara, 215–216. Tokyo: Iwanami Shôten, 1995.

Umezawa, Tadashi. Sarariiman no jikakuzô (Salarymen’s Self-Images). Tokyo: Minerva Shobô, 1997.

Uno, Kathleen. “Womanhood, War, and Empire: Transmutations of ‘Good Wife, Wise Mother’ before 1931.” In Gendering Modern Japanese History, edited by Barbara Molony and Kathleen Uno, 493–519. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Asia Center/Harvard University Press, 2005.

Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo. Nippon Modern: Japanese Cinema of the 1920s and 1930s. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

White, Jerry. The Films of Kiyoshi Kurosawa: Master of Fear. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2007.

White, Merry. Perfectly Japanese: Making Families in an Era of Upheaval. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Endnotes

1 In this paper, Japanese names generally appear in Japanese order – surname followed by personal name. However, in a couple of instances names of authors with Japanese names writing in English follow the English language naming order – personal name, followed by surname. Macrons are used to indicate extended vowels, except in the case of place names commonly known in English (for example, Tokyo, rather than Tôkyô), and Japanese names of authors writing in English, who do not themselves indicate extended vowels in their names with a macron.

2 Andrea Germer, Vera Mackie, and Ulrike Wöhr, “Introduction: Gender, Nation and State in Modern Japan,” in Gender, Nation and State in Modern Japan, eds. Andrea Germer, Vera Mackie, and Ulrike Wöhr (London: Routledge, 2014), 1–2.

3 See Barbara Molony and Kathleen Uno, “Introduction,” in Gendering Modern Japanese History, eds. Barbara Molony and Kathleen Uno (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Asia Center/Harvard University Press, 2005), 1–35. Also, Germer, Mackie, and Wöhr, “Introduction,” 1–24.

4 Sidona Blätter, “Identity Politics: Gender, Nation and State in Modern European Philosophy,” in Gender, Nation and State in Modern Japan, eds. Andrea Germer, Vera Mackie, and Ulrike Wöhr (London: Routledge, 2014), 277–278.

5 Romit Dasgupta, Re-reading the Salaryman in Japan: Crafting Masculinities (London: Routledge, 2013), 5–8.

6 Raewyn Connell, The Men and the Boys (St. Leonards, NSW, Australia: Allen and Unwin, 2000), 10. Also, Raewyn Connell and James W. Messerschmidt, “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept,” Gender and Society 19.6 (2005), 832. Hegemonic masculinity as a concept has since been deployed extensively, sometimes in ways not necessarily intended by Raewyn Connell when she first theorized the concept. For discussion and critiques of the various applications of the concept see, Connell and Messerschmidt, “Hegemonic Masculinity,” 829 –859; also Christine Beasley, “Rethinking Hegemonic Masculinity in a Globalizing World,” Men and Masculinities 11.1 (2008): 86–103; James W. Messerschmidt, “Engendering Gendered Knowledge: Assessing the Academic Appropriation of Hegemonic Masculinity,” Men and Masculinities 15.1 (2012): 56–76. While I am aware of the criticisms of the concept, I still believe that it is a useful tool of analysis, particularly in the context of the present discussion.

7 Connell and Messerschmidt, “Hegemonic Masculinity,” 832

8 Dasgupta, Re-reading the Salaryman, 7–8.

9 In this paper, I use both ideology and discourse as theoretical underpinnings framing my discussion. While the two concepts may be (and often are) treated independently, they are, nevertheless intertwined, particularly in my application of the concepts. While ideology has a myriad of meanings and applications, my deployment of the term references it as “a set of ideas through which people fashion themselves and others within specific socio-historical contexts, and through which the prosperity of certain groups is concerned,” Dani Cavallaro, Critical and Cultural Theory: Thematic Variations (London, The Athlone Press, 2001), 76. In this regard, ideology may be thought of as one of the “tools” through which hegemony operates, a “particular set of effects within discourses,” Terry Eagleton, Ideology: An Introduction (London, Verso 1991), 194. I use discourse in the sense of a body of knowledge built around specific culturally and historically produced meanings – thus the discourse of the salaryman would refer to all the meanings, articulations, actions, associations, and practices built up around the term. Moreover, discourses are processes that have ideologies – of class, of gender, of nation, for instance – embedded within them. In this sense, discourse is not only a process in and of itself, but also an ideological process.

10 Vera Mackie, “Embodiment, Citizenship and Social Policy in Contemporary Japan,” in Family and Social Policy in Japan: Anthropological Approaches, ed. Roger Goodman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 200–203.

11 Merry White, Perfectly Japanese: Making Families in an Era of Upheaval. (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2002),11.

12 Peter Matanle, “Beyond Lifetime Employment? Re-fabricating Japan’s Employment Culture,” in Perspectives on Work, Employment and Society in Japan, eds. Peter Matanale, and Wim Lunsing (Houndmills and New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 58–78.

13 Futoshi Taga, “Kojin-ka shakai ni okeru ‘otokorashisa’ no yukue: Sarariiman no ima-tokore kara (The Future Direction of ‘Masculinity/Manliness’ in an Individualized Society: From the Salaryman’s Present Position),” in Yuragu sarariiman seikatsu: Shigoto to katei no hazama de (Unstable Salaryman Life: Between Work and Family), ed. Futoshi Taga (Tokyo, Minerva Shobô, 2011), 187–217.

14 See Vera Mackie, Feminism in Modern Japan: Citizenship, Embodiment and Sexuality (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003), 21–25; also Molony and Uno, “Introduction,” 1–35.

15 See Shizuko Koyama [trans Vera Mackie], “Domestic Roles and the Incorporation of Women into the Nation-State: The Emergence and Development of the ‘Good Wife, Wise Mother’ Ideology” in Gender, Nation and State in Modern Japan, eds. Germer, Mackie, and Wöhr, 85–100. Also Kathleen Uno, “Womanhood, War, and Empire: Transmutations of ‘Good Wife, Wise Mother’ before 1931” in Gendering Modern Japanese History, eds. Molony and Uno (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Asia Center/Harvard University Press, 2005), 493–519.

16 In reality though various competing discourses about masculinity also circulated in the public sphere during these crucial formative decades. See Jason Karlin, “The Gender of Nationalism: Competing Masculinities in Meiji Japan,” The Journal of Japanese Studies 28.1(2002): 41–77.

17 See, Earl H. Kinmonth, The Self-Made Man in Meiji Japanese Thought: From Samurai to Salaryman (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981); Akira Iwase, “Gekkyû hyaku-en” sarariiman: Senzen Nihon no “heiwa”na seikatsu (The "Hundred Yen a Month” Salaryman: The “Peaceful” Lifestyle of Prewar Japan) (Tokyo: Kôdansha, 2006); Romit Dasgupta, Re-reading the Salaryman, 25–29.

18 Tadashi Umezawa, Sarariiman no jikakuzô (Salarymen’s Self-Images) (Tokyo: Minerva Shobô, 1997), 4. Also, Iwase, “Gekkyû hyaku-en” sarariiman, 24–26.

19 Kinmonth, The Self-Made Man, 277–280.

20 See, for instance, Miriam Silverberg, “Constructing the Japanese Ethnography of Modernity, ” Journal of Asian Studies 51.1 (1992): 30–54; Harry Harootunian, Overcome by Modernity: History, Culture, and Community in Interwar Japan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000); Molony and Uno, “Introduction,” 4–7; Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano, Nippon Modern: Japanese Cinema of the 1920s and 1930s (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008); Alisa Freedman, Tokyo in Transit: Japanese Culture on the Rails and Road (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011).

21 Sôichi Ôya, Ôya Sôichi zenshû (Collected Works of Ôya Sôichi) (Tokyo: Sôyôsha, 1981), 90–101.

22 Sôichi Ôya, Ôya Sôichi zenshû (Collected Works of Ôya Sôichi) (Tokyo: Sôyôsha,1981); Harootunian, Overcome by Modernity, 202.

23 Hajime Maeda, Sarariiman monogatari (Tales of the Salaryman) (Tokyo: Tôyô Keizai Shinpôsha, 1928); Kitazawa Rakuten Kenshô Kai (Kitazawa Rakuten Memorial Association), ed. Rakuten manga-shû taisei: Taishô-hen (Compilation of Collected Rakuten Manga: Taishô Collection) (Tokyo: Gurafikku-sha, 1973); also Kinmonth, The Self-Made Man, 289–290.

24 Hidetomi Tanaka and Muneyoshi Nakamura, “Wasurerareta keizai-shi ‘Sarariiman’ to Hasegawa Kunio (Hasegawa Kunio and the Forgotten Business Journal ‘Sarariiman’ [‘The Salaryman’]),” Festschrift for the 30th Anniversary of Jôbu University, Joint Publication of the Department of Commercial Science 10.2 (1999), and Department of Management and Information Science 20 (1999), Jôbu University: 1–22.

25 Robert E. Cole and Ken’ichi Tominaga, “Japan’s Changing Occupational Structure and Its Significance,” in Japan’s Industrialization and its Social Consequences, ed. Hugh Patrick (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), 74.

26 Harue Fujii, Nihon-gata kigyô shakai to josei rôdô: Shokugyô to katei no ryôritsu o mezashite (The Japanese Model of Industrial Society and Female Labour: Aiming for a Work/Home Balance). (Tokyo: Mineruba Shobô, 1995), 129.

27 See William W. Kelly, “Finding a Place in Metropolitan Japan: Ideologies, Institutions, and Everyday Life,” in Postwar Japan as History, ed. Andrew Gordon (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 197–198.

28 Hiroshi Hazama, Keizai taikoku o tsukuriageta shisô: Kôdo keizai seichô-ki no rôdô-êtosu [The Philosophy that Built-up the Economic Superpower: The Labour Ethos of the High-Speed Economic Growth Period] (Tokyo: Kôshindô, 1996), 26–29, 76–79.

29 Chizuko Ueno, “Kigyô senshitachi [Corporate Warriors],” in Danseigaku: Nihon no feminizumu bessatsu [Men’s Studies: Special Edition of Japanese Feminism], eds. Teruko Inoue, Chizuko Ueno, and Yumiko Ehara (Tokyo: Iwanami Shôten, 1995), 215–216.

30 As with the discourse of salaryman, the notion of the sengyô shufu did not reflect the reality that women were an integral part of the (primarily non-permanent) labor force, contributing to the economy without receiving the recognition and benefits extended to their fulltime male colleagues. See Mary C. Brinton, Women and the Economic Miracle: Gender and Work in Postwar Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983); also Priscilla A. Lambert, “The Political Economy of Postwar Family Policy in Japan: Economic Imperatives and Electoral Incentives,” The Journal of Japanese Studies 33.1 (2007): 1–28.

31 John W. Dower, “Peace and Democracy in Two Systems: External Policy and Internal Conflict,” in Postwar Japan as History, ed. Andrew Gordon (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 3–33.

32 See, for instance, Makoto Sataka, Keizai shôsetsu no yomikata: Keizai shôsetsu ga kaita Nihon no kigyô (How to Read Business Novels: Japanese Firms as Depicted in Business Novels) (Tokyo: Tokuma Bunko, 1991); Masao Tao, Kigyô shôsetsu ni manabu soshiki-ron nyûmon (An Introduction to Studying Organizational Theory in Business Novels) (Tokyo: Yûhikaku Sensho, 1996).

33 James E. Roberson, Japanese Working Class Lives: An Ethnographic Study of Factory Workers (London: Routledge, 1998), 7–8.

34 See, Ryôko Kodama, “Chichioya-ron no genzai: Nana-jû nendai ikô o chûshin toshite [Contemporary Fatherhood Debates: Focusing on the Seventies Onwards],” in Nihon no otoko wa doko kara kite, doko e iku no ka: Dansei sekushuariti keisei (Kyôdô kenkyûkai) [Where Have Japanese Men Come From, Where Are They Going?: Construction of Male Sexuality (Collaborative Research)], eds. Haruo Asai, Satoru Ito, and Yukihiro Murakami, (Tokyo: Jûgatsusha, 2001), 122–149. Also, Ayami Nakatani, “The Emergence of ‘Nurturing Fathers’: Discourses and Practices of Fatherhood in Contemporary Japan,” in The Changing Japanese Family, eds. Marcus Rebick and Ayumi Takenaka (London: Routledge, 2006), 96–97.

35 See Romit Dasgupta, “The 1990s ‘Lost Decade’ and Shifting Masculinities in Japan,” Culture, Society and Masculinity 1.1(2009): 73.

36 Romit Dasgupta, Re-reading the Salaryman, 39.

37 Hiroshi Satô and Atsushi Satô, Shigoto no shakaigaku: Henbôsuru hataraki-kata (The Sociology of Work: Changing Patterns of Work) (Tokyo: Yûhi Books, 2004), 69–71.

38 Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. White Paper on the Labour Economy 2005. Accessed October 15, 2016. www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/l-economy/

39 Precisely delineating the definitional parameters of “freeter,” a combination of the English term “freelance” and the German-derived Japanese term for casual work, arubaito, is, as Emma Cook points out, not as clear-cut as may be expected. For instance, the official definition has changed and narrowed at various points. Initially, freeter were defined as temporary, part-time or dispatched workers between the ages of 15 and 34. Subsequently the definition was tightened to exclude certain categories (like dispatched workers). Regardless of these definitional shifts, there is no denying that the proportion of (particularly) male freeter in the working population increased significantly over the 2000s, from 9.3 percent in the early-2000s to 18 percent in 2013. See Emma E. Cook, Reconstructing Adult Masculinities: Part-time Work in Contemporary Japan (Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, 2015), 13–15, 17–18. Accessed 7 October, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central. Also, Emma E. Cook, “(Dis)Connections and Silence: Experiences of Family and Part-time Work in Japan,” Japanese Studies 36.2 (2016): 156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2016.1215228

40 Akiko Takeyama, “Intimacy for Sale: Entrepreneurship and Commodity Self in Japan’s Neoliberal Situation,” Japanese Studies 30.2 (2010): 234.

41 Dasgupta, Re-reading the Salaryman, 39.

42 Futoshi Taga, “Tsukurareta otoko no raifusaikuru [The Constructed Life-cycle of Men],” in ‘Otokorashia’ no gendaishi [The Contemporary History of ‘Manliness/Maleness], eds. Tsunehisa Abe, Sumio Obinata, and Masako Amano (Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Hyôron-sha, 2006), 179–180; Mami Iwakami, “Chûkônenki no kazoku: Aratana seifuteinetto kôsaku ni mukete [Middle-aged Families: Towards Creating a New Safety Net],” in Koyô ryûdôka no naka no kazoku: Kigyô shakai, kazoku, seikatsu hoshô shisutemu [Family in a Time of Unstable Employment: Industrial Society, Family, Social Security System], Kazoku shakaigaku kenkyû shiriizu [Family Sociology Studies Series], eds. Keiko Funabashi and Michiko Miyamoto (Kyoto: Mineruba (Minerva) Shobô, 2008), 123–126.

43 See Takeyama, “Intimacy for Sale,” 231–246; Ian Condry, “Love Revolution: Anime, Masculinity, and the Future,” in Recreating Japanese Men, eds. Sabine Frühstück and Anne Walthall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 262–283; Kosuke Mizukoshi, Florian Kohlbacher, and Christoph Schimkowsky, “Japan’s Ikumen Discourse: Macro and Micro Perspectives on Modern Fatherhood,” Japan Forum 28.2 (2015): 212–232, http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.library.uwa.edu.au/10.1080/09555803.2015.1099558

44 Sabine Frühstück and Anne Walthall, “Introduction: Interrogating Men and Masculinities,” in Recreating Japanese Men, eds. Sabine Frühstück and Anne Walthall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 10.