Volume XIV, No. 2: Spring 2017

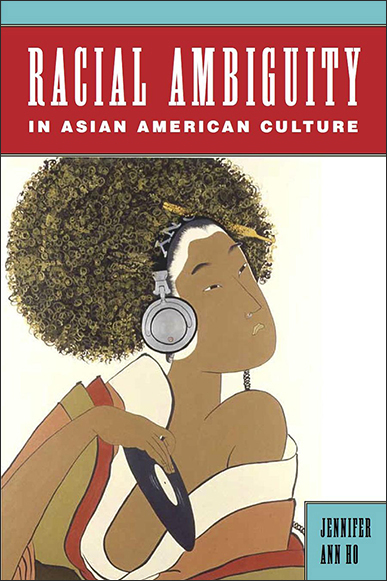

Racial Ambiguity in Asian American Culture, by Jennifer Ann Ho

![]() Download this Article as a PDF file

Download this Article as a PDF file

When citing this article, please refer to the PDF which includes page numbers.

Racial Ambiguity in Asian American Culture (Rutgers University Press) by Jennifer Ann Ho is a slender monograph that packs theoretical punch. Much of Ho’s analysis focuses on interracial family formation, and on the epistemic and identity crises that interraciality entails in an American polity premised on monoracial myths. In the introduction, Ho provides a useful overview of Asian American studies from its genesis in the late 1960s to the present. Here she also foregrounds her argument that ambiguity “is the only truly productive lens through which to view race” because race as a social construct is “protean” and “inherently unstable” (p. 4). Each of the five chapters that follows is a self-contained case study of varying types of racial ambiguity, whose juxtaposition suggest a theoretical whole larger than the sum of the book’s parts. A recurring theme is that racialized people are forced into singular and simplistic identity categories that belie the complexity and fluidity of their heritage, subjectivity, and self-expression.

Chapter 1 re-examines Japanese American internment during World War II through a little-known “Mixed-Marriage Policy” that exempted the wives and children of white Americans as well as non-white citizens of “friendly nations.” Chapter 2 explores the transnational adoption of East Asian children by primarily white American parents. Chapter 3 unpacks the contested racial identity of Tiger Woods, widely hailed as African American to the exclusion of his Thai heritage. Chapter 4 gives a nuanced reading of racial subjectivity, performativity, and “passing” in recent works by mixed-race Asian American authors Paisley Rekdal and Ruth Ozeki.

Chapter 1 re-examines Japanese American internment during World War II through a little-known “Mixed-Marriage Policy” that exempted the wives and children of white Americans as well as non-white citizens of “friendly nations.” Chapter 2 explores the transnational adoption of East Asian children by primarily white American parents. Chapter 3 unpacks the contested racial identity of Tiger Woods, widely hailed as African American to the exclusion of his Thai heritage. Chapter 4 gives a nuanced reading of racial subjectivity, performativity, and “passing” in recent works by mixed-race Asian American authors Paisley Rekdal and Ruth Ozeki.

The final chapter, Chapter 5, moves beyond the consideration of interracial families to question the racial boundaries of “Asian American literature.” Ho argues for including “transgressive texts” in the canon. By transgressive texts, Ho means texts written by authors who are not Asian American, which nevertheless advance the political program “of social justice and anti-essentialism” (144) that Ho positions at the core of Asian American studies. While Ho expresses sympathy with the impulse to privilege Asian American authorship, she deems that privilege “problematic because it implicitly casts racial identity as the barometer for authenticity and hence valued knowledge” (141). Whether the field is ready to jettison the principle of Asian American authorship is a poignant question, and one hopes more scholars will join Ho in the debate.

In a brief and elegant coda, Ho ties her scholarly arguments to personal testimony about growing up “Chinese Jamaican,” an autonym Ho abandoned as an undergraduate in California in favor of the more legible “Asian American.” Yet she never abandoned her sense of otherness and ambiguity “because I do, at heart, identify as Chinese Jamaican” (151). What’s in a name, what’s in a face, and what’s in a race are questions that continue to vex American politics and personhood, and Ho’s chapters bring into focus the inherent ambiguity of racial identity through a variety of analytic lenses. Ho is a professor of English and comparative literature, but her eclectic text offers something for everyone, ranging as it does from military history to the history of golf, from canonized literature to popular culture and digital ephemera like blogs.

At times, the reader may wish that Ho had done more analysis across chapters with their varied topics and lenses, highlighting links and ruptures while carrying theoretical insights from one chapter to the next. To take one example, Ho’s reconceptualization and celebration of racial “passing” in Chapter 4 is fresh and provocative, and deserves to be woven as an intellectual thread throughout the fabric of the book. But Ho’s discussion of “passing” begins and ends when the chapter does, leaving the reader to wonder, of the people and texts populating other chapters, whether all are “passing,” none are “passing,” or if “passing” has somehow lost its interest as an analytic mode. Upon reading the coda, one might ask: Is Ho herself “passing” as Asian American? Am I, the reader, “passing” as well? It does credit to the author that her book inspires novel and weighty questions. But for answers, one must look elsewhere.