Volume XIV, No. 2: Spring 2017

Eurasians and Racial Capital in a “Race War”

REFERENCES | AUTHOR BIO | ![]() Download this Article as a PDF file

Download this Article as a PDF file

When citing this article, please refer to the PDF which includes page numbers.

Keywords: Eurasian, mixed-race, Japan, Pacific War, race relations

For many, contemplating the Eurasian experience in Japanese history evokes the dilemma posed by the thousands of “occupation babies” fathered by Allied personnel stationed in Japan after the Pacific War during the Allied Occupation (1945-52).1 The discrimination faced by these orphans is well documented. Both Japan and the U.S. avoided either acknowledging or ameliorating the problem, feeling that to do so would be to admit responsibility for it. Occupation authorities (SCAP) neither extended aid to nor acknowledged legal responsibility for the unwanted children. SCAP denied requests from American personnel to bring their Japanese brides and biracial children to the U.S. by citing the 1924 Immigration Law blocking the immigration of Japanese and half-Japanese. It also forbade Japan’s Welfare Ministry from conducting a census of occupation babies.2 In June 1948, Saturday Evening Post journalist Daniel Berrigan published a critique of American GIs for fathering illegitimate babies and Occupation authorities for failing to take responsibility for them. SCAP responded by expelling Berrigan from the country and censoring any further media coverage of the issue.3 Japan’s government complied with and reciprocated the U.S. position. American and Japanese joint abhorrence and disavowal of the occupation baby problem thus amounted to what Yukiko Koshiro describes as “diplomatic collaboration in tolerating mutual racism. Their mutual hatred of miscegenation drew them closer.”4

The Japanese public echoed the state’s abhorrence for this population of biracial babies. Whereas Japanese enthusiastically embraced cultural mixing with the U.S., they rejected biological mixing outright, seeing mixed-race babies as a threat to their racial purity and tantamount to an assault on the Japanese race itself. Black-Japanese babies were especially despised, but all biracial mixtures encountered greater prejudice in Japan than did biracial “GI babies” in Germany and Britain.5 Even Sawada Miki (沢田美喜, 1901-80), who in 1948 founded an orphanage for occupation babies, defended the policy of separating Japanese and biracial orphans. Mixed-race children, she felt, possessed “mental and physical handicaps” and in any case would never be accepted into Japanese society due to “the people’s traditional dislike for Eurasian children.”6 By 1955, Sawada’s orphanage had accepted 468 babies and negotiated 262 adoptions in the U.S. No Japanese adoption service accepted Sawada’s children, however, and a Japanese couple who had adopted one “returned it when the neighborhood prejudice they encountered proved too strong.”7

The pervasive ethnocentrism and tribalism suggested by postwar Japan’s treatment of Eurasian babies does not necessarily reflect the Eurasian experience in Japan during the war, however. Race and racial mixing during Imperial-era (1895-1945) Japan were highly politicized, formulated and deployed as means of advancing an altogether different set of national interests. In the 1930s-40s, for example, Japanese pan-Asianism drew clear racial lines between “yellows” and “whites.” Conceding that mixed blood flowed within all Asians, Japan easily accepted its Asian colonial subjects (mixed or not) as “Japanese.”8 Doing so required nothing more than rhetorical acknowledgement of historical blood ties between Japan and continental Asia.9 This racial grouping problematized the place of Eurasians, particularly within Japan proper.10

Eurasian (for our purposes, part-Japanese/part-Caucasian only)11 civilians residing in wartime Japan indeed occupied undefined, contested spaces. As embodiments of two races at war with one another, on one hand their whiteness evoked an international racial order that equated national prestige with racial prestige (racial capital). On the other, their Japanese heritage evoked assumptions of spiritual and genealogical purity that informed longstanding nationalist claims of Japanese racial supremacy. Wartime Japan’s methods of handling Eurasian residents were thus framed, in part, by a convoluted discourse on race, racial characteristics, racial hierarchies, and a history of national racial soul-searching. Given these ambiguities, how did this small contingent experience the war? What were their strategies for reconciling the racially marginalized self with an increasingly xenophobic state?

This article considers these problems by seeking evidence of systemic (institutionalized) and non-systemic (“on the street”) discrimination and then determining the extent to which racial pretensions shaped Eurasian wartime experiences. In doing so, it engages with the pervasive view of the Pacific War as a “race war” fueled by “race hate.” This narrative was advanced most cogently in John Dower’s War without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific (1986), which showed how conflict in the Pacific was essentially a racial war between analogous racial regimes. Dower’s proposition is evident not only in the especially brutal ways that combatants engaged each other in the Pacific Theater, but also in the racial ideologies that shaped how those hostilities were prosecuted on both sides. Whereas many Americans viewed Nazis as a “bad” subset of otherwise racially irreproachable Germans, Dower explains, they saw the entirety of the Japanese people as racially inferior, a pestilence to be exterminated.12 In Japan, governmental and military ideologues likewise sought to instill fear and hatred of their “white” enemies, though the efficacy of those efforts is debatable. (Elsewhere I have elucidated the limitations of the “race war” thesis by showing the contexts in which wartime Japanese did and did not conceptualize the conflict in racial terms and exhibit racial hatred for their Caucasian enemies.)13 The race war discourse has failed to examine the issue through the lens of mixed-race experience, however. This article begins to fill this lacuna. Its focus on Eurasian residents of wartime Japan helps reappraise overarching characterizations of this war as driven by Japanese-Caucasian racial hatred.14 Examination of how Eurasians caught in wartime Japan were viewed and treated by Japanese authorities, the Japanese public, and resident Westerners finds that Eurasians’ official treatment was not racially determined. Containment protocols were dictated by an individual’s nationality, not racial heritage. Predictably, unofficial “on the street” treatment varied. With little recourse, the racially marginalized survived by devising strategies that often mitigated potential forms of discrimination, effectively de-racializing the war at home.

Race and mutual insularity in the prewar era

Interracial unions with Caucasians had been a point of controversy and concern for Japan since the appearance of Western settlements in the 1850s.15 Thereafter, racial attitudes would be molded from a mixture of sources, including nativist rhetoric about Japan’s indigenous true heart/mind (magokoro 真心), racist colonial narratives gleaned from the West, and claims advanced by racial science. This composite body of knowledge was brought into alignment with the logic of wakon yōsai 和魂洋才 (Japanese spirit, Western learning), a prominent Meiji-era (1868-1912) slogan that called for selective devotion to both the native and the foreign. Wakon invoked nativist claims of Japanese racial and spiritual supremacy; yōsai acknowledged the superiority of Western civilizational accomplishments, particularly those related to science and technology, and the need for Japan to improve itself in those areas. The slogan carried no sense of contradiction. Its assimilation of native and Western had been accepted since at least the 1770s when an affinity for Dutch (Western) Learning emerged concurrently with nativist thinker Motoori Norinaga’s (本居宣長, 1730-1801) intellectual arguments for Japanese superiority.16

Japan’s goal of joining the elite members of the global order raised questions of how Japanese, as a race, compared to others, a topic that many were quick to explore through Western rather than nativist tropes. Particularly, its acceptance of the West’s apprehension of racial hierarchies connoted adherence to a system of racial capital. In the 1860s, Japanese missions to the U.S. and Europe felt no compunction about accepting the prejudicial views toward “darker” races prevalent in those nations. They exhibited moral indifference to slavery in the U.S., for example, seeing it, as many Americans did, as a natural reflection of inherent racial inequities.17 Preeminent Western expert Fukuzawa Yukichi (福沢諭吉, 1835-1901), himself a member of the 1860 mission, connected racial distinctions to geography, as well as biological differences like skin color. To deny self-evident physical differences, he wrote in Handbook of the Myriad Countries (Shōchū bankoku ichiran 掌中万国一覧, 1869), denies the reality of qualitative racial distinctions. He continued by positing a five-color racial hierarchy of whites, yellows, reds, blacks, and browns that used civilizational advancement as evidence of racial superiority. “The white races have sagely minds and natures that elevate them to the pinnacle of civilization. They are the highest,” Fukuzawa wrote. “Yellow races have stoic dispositions and apply themselves diligently, but progress more slowly due to their limited abilities.”18 Reds, blacks, and browns, he continued, possessed more degraded dispositions.

Other theorists interpreted the technological leadership of Western peoples as evidence of their inherent physical and intellectual superiority. Historian and social critic Kume Kunitake (久米邦武, 1839-1931) argued that inherent dispositions are codified within each society’s structure and political organization, which ultimately determine respective potentials for civilizational advancement. Of the differences between Westerners and Asians, he writes,

…white races actively pursue their yearnings, have a passion for religion and are poor at restraining themselves; in short, they are races with deep desires. Yellow races have shallow desires and are good at restraining their natures; in short, they are races with few desires. Accordingly, the West’s main political objective is to seek self-protective government while that in the East is to seek ethical government.19

For Kume, then, the competitiveness, aggressive striving, and technological advancement observable in Western societies were explained by inherent racial dispositions. It was indeed on such grounds that Japan spearheaded its own development by actively recruiting Western scientists, engineers, industrialists, business professionals, and educators, a cohort that arrived in Japan espousing theories – like natural selection and craniometry – that claimed to explain physical and intellectual differences between races in scientific terms. Such theories placed Japanese below Caucasians but above other races, including Chinese. The Japanese also saw that they were being treated better by Westerners than other Asians, which seemed to validate nativist assertions of their indigenous racial superiority.20

Social Darwinism became a particularly useful principle for elucidating what Kume and others felt to be immutable and indisputable natural laws. It explained the successes and failures of certain racial groups coexisting in Japanese society, for example, by interpreting the failure of the poor, the burakumin 部落民, and other marginal classes as natural results of intrinsically inferior natures.21 Kume also drew parallels between the eradication of American Indians by “blond, white-skinned” Americans and Japan’s subjugation of the Ainu in Hokkaido and northern Honshu. Such conquests, he asserted, were natural given the relative racial strengths of those competing ethnic groups. While Social Darwinism was gradually rejected by many academics, it would later enable Imperial-era ideologues to interpret Japan’s technological and economic advancement as evidence of racial superiority in Asia.

Such paradigms did not go uncontested, however, with some liberals recoiling against them as early as the 1880s. Journalist and activist Sugita Teiichi (杉田定一, 1851-1929) encapsulated general indignation with his declaration that “despite the superior consciousness of the yellow races, the fact that they are viewed as inferior by whites is not easily ignored and wounds Japanese self-esteem”22 Others countered by positing Japanese preeminence in Asia. Leftist instigator Ōi Kentarō (大井憲太郎, 1843-1922) argued that Japanese were superior among the yellow races but were not being recognized as such by whites. Ideological backlash of this sort stressed a need for Japan to isolate itself both from inferior Asian races and from the presumptions of racial superiority being advanced by Caucasians.23 In the ensuing decades, military victories over China (1895) and Russia (1905) lent validity to Japan’s growing racial self-confidence, to its claim as the “white” (leading) race of Asia and of the Japanese people as “honorary whites.”24 Yet it soon became clear that the West did not share this perspective, but rather viewed Japan as a “yellow peril” whose military exploits were upsetting the racial status quo in Asia.

Those debating racial dispositions and biological superiorities were also attracted to other claims advanced by racial science. Scientific inquiry in the 1880s informed discussions over whether to permit “mixed residence in Japan” (naichi zakkyo 内地雑居), a controversial prohibition that was finally overturned in 1899 when revisions to the unequal treaties granted foreigners the right to live and travel anywhere within the country (Figure 1).25 While some Japanese argued that the interracial unions that would surely arise from legalizing mixed residence would strengthen the race, philosopher Inoue Tetsujirō (井上哲次郎, 1855-1944) and others used racial science’s defense of racial purity, a position broadly accepted in the West, to argue the opposite. This group applied knowledge gleaned from cross-breeding experiments on nonhuman species as evidence of the genetic defectiveness of mixed-race individuals and the social dangers they posed. When asked by former Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi (伊藤博文, 1841-1909) to weigh in on this debate, imminent philosopher and scientist Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) advised Japan to avoid intermarriage, unions that science had shown to produce inferior offspring. In 1918, American sociologist Edward B. Reuter (1880-1946) echoed this position (as well as public sentiment) when he wrote that Eurasians

stand between two civilizations, but are part of neither. They are miserable, helpless, despised and neglected… In manhood [the Eurasian] is wily, untrustworthy and untruthful. He is lacking in independence and is forever begging for special favors… Socially the Eurasians are outcasts. They are despised by the ruling whites and hated by the natives.26

These views seemed to lend validity to the correlated myth of Japanese racial purity. Following on assertions that Japan had historically avoided immigration and miscegenation, wartime state propaganda expounded on the virtues of “consanguineous unity,” positing that “the Imperial blood may be said to run in the veins of all Japanese,” rhetoric that cemented myths of the Japanese polity as a racially unified, homogenous family state headed by the emperor.27

The convoluted discourse on race that spanned Japan’s imperial era thus yielded paradoxical values that espoused the racial superiority of both pure Caucasians and pure Japanese, a worldview that helped validate mutual exclusivity. By tacit agreement and force of habit on all sides, Westerners and Japanese in prewar Japan thus preserved much of the insularity that had been erected between the races during the 1850s. As Yokohama resident Lucille Apcar notes, her family’s insularity from Japanese was mutually generated and mutually desirable: “Snobbery,” she writes, “if that is the word to use, existed on both sides of the fence.”28

Japanese and Western treatment of resident Eurasians

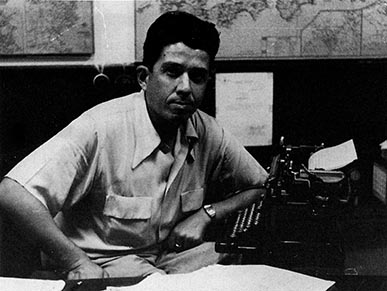

Significantly, Japan was careful to avoid throwing its selective espousal of Western racial thought back in the faces of its Western adversaries. In the interwar years, states in the U.S. acted on fears of intermarriage by passing anti-miscegenation laws and restricting immigration from racially undesirable nations—Asian nations particularly. Wishing to assume the moral high ground, Imperial-era Japan did not reciprocate by instituting analogous forms of systemic racism against Westerners, resisting such policies through the war itself.29 Unlike Executive Order 9066 (1942), which interned 120,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry in the Western U.S., of whom roughly two-thirds of carried American citizenship, wartime Japanese containment measures did not target resident Westerners on racial grounds.30 The government handled them as their citizenship dictated. Axis, neutral, and stateless nationals were surveilled but remained at large. Citizens of enemy nations were contained in various ways. The Interior Ministry’s Foreign Affairs Emergency Measures Plan (Gaiji kankei hijō sochi ni kan suru ken 外事関係非常措置に関する件) of November 28, 1941 instructed police to arrest enemy nationals falling into any of five categories: those enlisted in the military; crew members of ships or airplanes; males between the ages of 18 and 45; those with special skills such as radio operators and munitions factory experts; and any others that police deemed suspicious.31 Enemy nationals not included in the above – predominantly women, minors, and the elderly – were closely monitored by the police but not interned initially. Enemy diplomats were placed under house arrest until repatriation via exchange ship could be arranged. About 109 journalists and others of special concern were arrested, interrogated, variously tortured, and incarcerated until their repatriation by exchange ship. Officially, Eurasians were treated no differently than their full-blooded countrymen, i.e., as determined by their fathers’ citizenship. Edward Duer, who was thirteen in 1941, was neither interned nor evacuated. As a British citizen he continued living with his Japanese mother in southern Yokohama while his father William and older brother Syd were interned, first at the Yacht Club in Yokohama and later at the Uchiyama camp outside the city. The American boy Joe Hale (b. 1937), whose father had died and whose half-Japanese mother held Japanese citizenship, was permitted to move about Tokyo unhindered.32 American Eurasians Mary and Mildred Laffin evacuated Yokohama for their summer house in Hakone and were left untouched throughout the war. Their sister Eleanor, however, continued to occupy the Laffin house in Yokohama and was removed and interned in December 1943 after authorities found the house to be situated within the fortified coastal zone off limits to foreigners.33 Other multiracial enemy families were treated identically. In fact, Japanese civil and military police followed prescribed protocols for treatment of foreign nationals (including Eurasians) so meticulously that they had to feign negligence in order to justify arresting and holding the half-Japanese journalist James Harris (or Hirayanagi Hideo 平柳秀夫, 1916-2004). Harris had relinquished his British citizenship after his father died in 1933 and became a naturalized Japanese in order to remain in Japan with his mother. Though raised in Japan and fully bilingual, he was educated extensively in international schools and describes his worldview and physical appearance as British. As a trusted reporter for the English newspaper The Japan Times, Harris was too knowledgeable about Japanese current events and too well-connected with the enemy media to be allowed to remain at large after Pearl Harbor (Figure 2). Police, who had interrogated him earlier and knew him to hold Japanese citizenship, “mistakenly” arrested him as a British national and interned him in the Yacht Club camp. It was only upon his imminent “repatriation” via exchange ship months later that they admitted the error and allowed him to return to his mother’s house, where he was summarily conscripted into the Imperial Army.34

While prejudicial treatment of Westerners was not legally sanctioned, it was for Asians. In some cases, Japanese law did not recognize Asians’ foreign citizenship. Resolving to identify colonial residents by their original ethnicities, authorities issued policies that disavowed the citizenships of Asians living under Western colonial contexts: it rejected the American citizenship of Filipinos, the British citizenship of natives in Britain’s Asian colonies, the Dutch citizenship of natives in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), and the French citizenship held by natives of Vietnam and Cambodia. Likewise, the Interior Ministry considered second generation (Nisei) and returnee (Kibei) Japanese-Americans to possess dual citizenship and refrained from interning them.35 When Iva Toguri (アイバ・戸栗, a.k.a Tokyo Rose), an American citizen, requested to be interned along with her countrymen a policeman retorted: “since you are of Japanese extraction and a woman, I do not think you will be very dangerous. So we will not intern you. For the moment we will just see how things go.”36 Mary Kimoto Tomita (メリー・キモト・トミタ), another American Nisei, speculated that “since we look Japanese, I guess they thought it would be safe.”37

While prejudicial treatment of Westerners was not legally sanctioned, it was for Asians. In some cases, Japanese law did not recognize Asians’ foreign citizenship. Resolving to identify colonial residents by their original ethnicities, authorities issued policies that disavowed the citizenships of Asians living under Western colonial contexts: it rejected the American citizenship of Filipinos, the British citizenship of natives in Britain’s Asian colonies, the Dutch citizenship of natives in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), and the French citizenship held by natives of Vietnam and Cambodia. Likewise, the Interior Ministry considered second generation (Nisei) and returnee (Kibei) Japanese-Americans to possess dual citizenship and refrained from interning them.35 When Iva Toguri (アイバ・戸栗, a.k.a Tokyo Rose), an American citizen, requested to be interned along with her countrymen a policeman retorted: “since you are of Japanese extraction and a woman, I do not think you will be very dangerous. So we will not intern you. For the moment we will just see how things go.”36 Mary Kimoto Tomita (メリー・キモト・トミタ), another American Nisei, speculated that “since we look Japanese, I guess they thought it would be safe.”37

Within former foreign settlements like that in Yokohama, mixed residence gave way to an extraordinary cosmopolitanism that included large populations of mixed-race individuals. Japanese law subscribed to the jus sanguinis a patre principle of citizenship as determined by the paternal bloodline. As such, children with foreign fathers and Japanese mothers were denied Japanese citizenship. But as Harris’ case suggests, extenuating circumstances were not unusual. Fredrick DaSilva, for example, was half Japanese, one quarter Chinese, and one quarter Portuguese but was born in Japan and held British citizenship. He and his Japanese wife Takimoto Kiyoko 滝元清子 needed to register the births of their five children with the British Consulate within 90 days in order to claim British citizenship for them. Details are vague, but his son Joe Takimoto (1933-2015) would later write that the local ward office did not forward that paperwork for any of the children, who consequently became Japanese citizens. As a result, after Pearl Harbor as Fredrick was held at the Negishi race track internment camp in Yokohama; his sons Joe, Freddy, and Larry – Japanese citizens but minors in any case – attended St. Joseph’s College, where Joe was invited to sing for kamikaze pilots prior to their deployment.38

Despite the relative absence of systemic racism against Westerners and their mixed offspring, and despite the burgeoning cosmopolitanism in places like Yokohama, resident Westerners and Japanese alike had discriminated against Eurasians in non-systemic ways for generations. The Helm family serves as a case in point. Prussian engineer Julius Helm (1840-1922) arrived in Japan in 1869 and served as a military advisor in Wakayama. Several years later he received the government approval necessary to marry Komiya Hiro (小宮ヒロ).39 Julius went on to found Helm Brothers, Japan’s largest foreign-owned stevedoring company, and the Helm family remained a respected fixture within Yokohama’s foreign community for the next four generations. For Julius’ descendants, however, the family’s mixed blood was a chronic source of concern. Finding marriage partners proved especially difficult. Both of Julius’ two daughters were courted by half-Japanese suitors but ultimately never married. (The Helms were not unique in this regard. Though fluent in Japanese, none of Dutch businessman Isaac Ailion’s [1848-1918] six half-Japanese children were able to marry.40) Marriage prospects for Julius’ four sons varied according to their physical features, for Eurasians with lighter coloring were held in higher regard within Japan’s foreign communities, as well as within their own families. Jules, the darkest of the boys, married a half-Japanese/half-German like himself, whereas Jim’s lighter complexion enabled him to wed a Caucasian woman of high birth. Karl, the eldest, married a Caucasian first cousin, and Willie wed a Caucasian widow with children.

The Helms “believed they were better than the Japanese,” writes Leslie Helm. “Yet, of mixed blood and unable to read or write Japanese, they often felt insecure in the country of their birth.”41 Though the Helm siblings became prominent figures within their respective communities, they lacked the racial capital to merit full membership.42 Jim, who ran the Helm Brothers branch in Kobe and had travelled internationally, was active and popular in Kobe but his bloodline disqualified him from equal treatment:

He [Jim] and his charming wife moved in high circles. Jim raced in regattas, joined a water polo team and contributed large sums of Helm Brothers’ money to various charitable causes. His wife, Elizabeth, a brunette with a commanding presence and a beautiful voice, served two terms as president of the Kobe Women’s Club and often sang at special occasions. Still, it was hard to escape the issue of race. Jim would never forget overhearing his friends talk about him in the locker room at his sports club. ‘Jim’s a good sort,’ one man said. ‘Yes,’ said the other. ‘He knows his place.’43

The capital gleaned from one’s skin color and pedigree thus informed a racial taxonomy within Imperial Japan’s Western communities. Western residents projected their racial self-consciousness and racial preferences onto those around them, and Japanese reciprocated those preferences. Japan resident Estelle Balk (b. ca. 1898), a German Jew whose husband Arvid (1889-1955) was imprisoned during the war for espionage, voiced these pretensions at length as late as 1947. As she observed the mess hall for the Occupation’s military personnel, she reflected on the “strange features” discernible among those of “mixed breeding”:

As to the characters of this cosmopolitan crowd, I have found in my long years of experience in Japan that the mixture of yellow and white does not produce generally a homogenous personality, as whatever citizen papers they may have they somehow don’t feel at home in either community. This produces a split personality, which can either be surmounted by will, a deliberate choice of the individual, persuaded by physical likeness or by racial inclinations. A Eurasian for instance, in that case is more English or more German than the home born, pure racial individual, slightly ridiculous therefore by his convulsive endeavors. Nevertheless, he is the more valuable personality than the one who runs with the crowd of half casts [sic], ready to work for either side. That is all too often the case. They are therefore by nature unreliable. As a matter of fact, a great percentage of these half casts [sic] served the Kempetai 憲兵隊 [military police] as spies during the war. It is a scientific fact that the Eurasians inherit mostly the inferior qualities of both well-balanced races, which makes him into a dualistic individual. Of course, I too have good acquaintances among them, kind people if life runs smooth, but I would not dare to rely on them, if again caught here in the craze of a new war.44

Estelle Balk’s assessment of Eurasians is informed by the vagaries of racial science. She uncritically allows assertions that such individuals inherit the inferior qualities of both races, suffer from split personalities, and are thus preprogrammed with genetic disadvantages to stand as evidence of their inherent deceitfulness. But her convictions are also supported by personal experience. Her remark that Eurasians served the military police as spies refers specifically to her encounters with Patrick Tomkinson, a half-Japanese/half-American newspaper reporter for The Japan Times who worked as a police spy and interpreter during the war. Tomkinson had even helped police interrogate her and torture her husband Arvid.45 Estelle’s prejudices were also informed by her associations with Hugo Frank (1915-45), a German Jew who in 1939 married Alice (Chizuka ちづか) Sumimura 炭村 (1909-96), a half-Japanese woman. This union created consternation within Hugo’s own family. It also scandalized the Balks. Hugo worked with Arvid, and his brother Ludwig had married Estelle’s daughter. Though related by marriage and living in close proximity to Hugo, Alice, and their daughter Barbara (b. 1939), Estelle ostracized them throughout the war. Her 413-page memoir, in fact, makes no mention of Alice whatsoever.46

More surprising than the standing prejudices held by Westerners against Eurasians are instances of Eurasians exhibiting those pretensions themselves. We have already noted how, within the social contexts of Yokohama’s foreign community, the Helms saw their mixed blood as a source of shame and responded by marginalizing “darker” family members. Syd Duer, a Eurasian medical school student interned at the Uchiyama camp, writes that he and the other Eurasians there had difficulty forming close relationships with other inmates.47 Perceptions of Eurasians as untrustworthy, he suggests, held merit.

There are traitors amongst us that will even rat on their compatriots just to curry favour with [the camp guards]. We have no intention of doing harm to Japan nor are we in any position to do so. Common decency dictates we overlook each other’s petty infractions. But no, there are those among us who will report every trivial violation, and at times even by bending the truth. And the strange part of it all is that such traitors are all Eurasians. No wonder Eurasians generally are held in contempt. It could be that their upbringing drives them to such baseness.48

Though Duer explains Eurasian “baseness” in terms of upbringing rather than genetics, he nonetheless seems to internalize the same racially determined superiority and inferiority complexes espoused by Balk and the Helms.

Western racial bias notwithstanding, within the context of the Pacific “race war,” Eurasians were just as much “them” as they were “us,” and would seem to warrant a healthy measure of distrust from the Japanese populace. A preponderance of evidence indicates, however, that many Japanese were ambivalent to the Eurasians who remained at large during the war years. While wartime hardships and competition often reduced human relations to an “us” vs. “them” mentality, therefore, some Japanese were disinclined to blame full- or mixed-blooded Caucasians on the ground for the murderous bombs that (presumably) other Caucasians were dropping on them from above. That is, they did not view the war in racial terms.49 Western and Eurasian residents were included in neighborhood associations (tonarigumi 隣組), a system of mutual support and surveillance in which groups of five to fifteen adjacent households collectively coordinated air raid and firefighting drills, watched for spies, fought crime, sold savings bonds, and distributed rationed food. Each member’s active participation was integral to the entire association, and one imagines that the mutual dependence helped erase potential racial misgivings. Vera Uyehara (ビラ・上原, 1903-83), for example, the Caucasian wife of a former Japanese police superintendent, notes making friends with her Japanese neighbors and the mothers of her sons’ schoolmates.50 As a British Eurasian, Edward Duer reports that neither he nor the Gomes family, the other “enemy family” whose elder males were also interned at Uchiyama, were treated differently by their tonarigumi members. “Most of [our neighbors] were actually sympathetic to our situation with the ‘rice winners’ in the families in a far-off internment camp,” Duer writes.51 His account of the massive incendiary bombing on May 29, 1945 indeed reveals no local resentment toward him and his family. During the bombing, he relates, their neighbor’s house caught fire, which soon spread to the Duer home. Home alone at the time, Edward fled.

As I started for the gate a bomb dropped with a thud on the bare ground right in front of me. Maybe it was a dud as it did not explode, but of that I am not quite sure. Whatever it was, some brownish, semitransparent slimy substance oozed out of the casing, a hexagonal steel cylinder about 50 cm long and 10 cm in diameter. It caught fire, so it may not have been a dud after all, and I tried to stamp it out with my shoes. To my horror not only did the burning ooze resist my efforts it almost seemed alive and climbed up my shoe continuing to burn. In a panic I thrashed about and somehow I put out the flames.52

When the bombing ceased, residents emerged from their bomb shelters, Edward among them, at which point, “suddenly we looked at each other and burst out laughing.”53 His brother Syd’s own perspective on this event also reflects on the extraordinary magnanimity that locals extended toward Edward and his mother:

As far as is known so far, none of the family members of the [Eurasian] internees has suffered injury. Eddie [Edward] says that our neighbors are all extremely kind to them. Aren’t we their enemies? And isn’t all this the work of enemy planes? The government has tried to inculcate hatred of the enemy onto the minds of its citizens, but that has been defeated totally by their unquenchable warmth. This war is truly only a battle of government against government.54

Duer’s assertion that propaganda failed to imbue the Japanese populace with fear and hatred of whites certainly challenges the pervasive “race war,” “race hate” thesis. Though further discussion of such is beyond the scope of this paper, Duer’s observation directly corroborates numerous testaments of Westerners living through the war years in Japan. By all accounts, wartime hardships appeared to soften rather than harden Japanese views of Caucasians and Eurasians in their midst.55

The leniency shown to Eurasians was not particular to women and children.56 Eurasian men, irrespective of their nationality, also benefited from the Japanese public’s racial ambivalence. Syd Duer, who spoke fluent Japanese, encountered no suspicion or hostility when sent by his internment camp commander into neighboring communities on errands and work details. John Morris, a British national teaching English at a university in Tokyo, encountered very little anti-British feeling even after the outbreak of war. Immune from arrest and internment as a guest of the government, Morris claims that his Japanese friends did not hesitate to visit and interact with him and that many brought him generous gifts of food.57 Vera Uyehara’s son Cecil, a Japanese citizen, was treated no differently than his peers at Keio University. In 1944 he and his Keio classmates were taken to perform labor at factories and shipyards before being conscripted the following year. Though Uyehara’s mixed blood was conspicuous within both the university and military settings and carried great potential for ostracism and maltreatment, as a serious young man with a strong sense of responsibility he was able to mitigate racial abuse through hard work. Ultimately, his treatment in the university and then the army was no worse than that of his full-blooded Japanese peers.58

Racial capital in a race war

Seeking evidence of systemic and non-systemic racial discrimination against Eurasians in wartime Japan calls for meticulous attention to their various status positions within a broad taxonomy of resident civilians. Officially, treatment was determined by nationality and thus dispensed irrespective of race. Eurasians carrying Japanese citizenship were treated no differently than full-blooded Japanese, and those carrying foreign citizenship were treated no differently than full-blooded Westerners. In principle and with few exceptions, therefore, systemic racism toward these individuals did not exist within Japan proper, though we must also note that systemic protections against racial discrimination did not exist either.

In social (unofficial) contexts, in contrast, a long tradition of racially motivated mutual insularity engendered a range of attitudes toward Eurasians, including forms of exclusion from their respective pure-blooded communities. Though mutual insularity and the racist pretensions that informed it were not systemic, they were normative and presented Eurasians with a number of obstacles. As the Helms’ case illustrates, elites within Yokohama’s foreign community indeed harbored prejudicial attitudes throughout the era. The fact that Syd Duer and the Helms themselves subscribed to these views validates Frantz Fanon’s explanation of how the racially marginalized become psychologically dependent upon racial elites, vested in discriminatory social relations, and ultimately accepting of their degraded positions.59 Rather than challenging prejudice, some Eurasians felt ashamed of their pedigrees. Unofficial “on the street” racism, therefore, was somewhat more contextual, but tended to hinge on longstanding assumptions surrounding racial prestige (racial capital).

Race relations and racial discrimination between Westerners, Japanese, and Eurasians in imperial-era Japan were highly variable, of course. Caucasian residents espoused different opinions of miscegenation and mixed-race offspring, as well as about the superiority of their own race. Resident Americans were comparatively more insulated and willing to adapt to life in Japan, Koshiro finds. Hyogo prefecture census data from 1935 reveals that only 3.4% of American residents had married Japanese, compared to 16.5% of French, 13.3% of Swiss, 11.6% of British, and 8.1% of Germans.60 Japanese also responded to the fact that, as several sources attest, German residents made greater efforts than other Westerners to learn Japanese and integrate into Japanese society. Their affinity for Japanese culture made Germans more flexible and open to Japanese customs and etiquette than other nationalities.61 And while racial pretensions varied, they were nonetheless projected upon and subsequently reciprocated by Eurasians and Japanese. Indeed, one suspects that the paucity of mutually desirable Caucasian suitors was responsible for leaving Eurasians like the Helms and the Ailions either unmarried or wedded to other Eurasians. Syd Duer mentions that, as a youth, he was attracted to Japanese girls and assumed that he would eventually marry a Japanese woman, which he did.62

Wartime contexts thus yielded an array of contingent experiences, but they did not intensify racial hostility to the degree that Japanese ideologues had hoped. Rhetorical depictions of resident Westerners as spies and demons contradicted what Japanese had learned to be true from generations of personal experience, and ultimately proved unsuccessful in erasing Caucasians’ racial capital. For the Japanese public, wartime hardships – deaths of family and friends, severe shortages, imminent air raids, occupational disruption, and evacuations – intensified competition for basic resources. Amidst citizens’ struggle for survival, hardships streamlined human relationships and eroded the relevance of race. Adversity bolstered the perceived value of community.63 In this regard, Japanese who were focused on self-preservation found solidarity with Caucasian and Eurasian neighbors more beneficial than mutual suspicion. As noted, the racial ambivalence exhibited by many Japanese for Westerners and Eurasians in their midst lends great context to the overt forms of racial discrimination, systemic and otherwise, that they directed toward other Asians. Chinese and other Asian immigrants faced racial hostility and widespread discrimination from the Japanese public (Lucille Apcar’s Japanese maids called local Chinese “evil”).64 Such attitudes extended even to individuals of Japanese ancestry born in the U.S., who upon entering Japan faced harassment and suspicion.65 Many of the roughly 20,000 second-generation Japanese-Americans trapped in Japan during the war indeed suffered discriminatory treatment within their local communities.66

What strategies, then, did Eurasians use to reconcile the marginalized racial self with the systemic? Whether navigating Western communities or Japanese society, Eurasians were able to minimize the offensiveness of their mixed blood by possessing relative wealth or status, bilingual and bicultural skills, a reputable nationality, and a comparatively moderate (inoffensive) skin color. As Lily Anne Yumi Welty writes in reference to mixed-race Okinawan Americans, they “strategically deployed multiple identities as forms of engagement and resistance,” for “racial ambiguity provided them with situational agency.”67 The Helms’ deep roots and philanthropic activities in Yokohama earned them considerable local respect that compensated for their comparative lack of racial capital. Cecil Uyehara, James Harris, and the Duers used diligence and trustworthiness to mitigate racial hostility and establish reputations that were beyond public reproach. For these individuals smoothing social relations was an exercise in self-preservation. Both systemically and non-systemically – at the levels of both official containment and “on the street” social relations – we find less evidence of a race war driven by racial hatred than the prominence of that discourse would suggest. Duer’s assessment of the war as “truly only a battle of government against government” – and, we would add, military against military – is sound, for it was within only those contexts that racial enmity was widely manifested.

Placed within broader historical context, this comparatively inclusive treatment is unexpected. During the 1930s and ‘40s, the Japanese state quashed public alarm over its own insurgent militarism by formulating its wars in Asia and the Pacific as racial crusades (race wars). Following defeat in 1945, it sought reacceptance into the international community by following the lead of the Allied Occupation and vigorously disavowing racial enmity. Astonishingly, the “occupation baby” phenomenon suggests that throughout the course of this dramatic wartime-postwar paradigm shift, grassroots racial attitudes toward Eurasians variously evolved in the opposite direction expected: from more racially tolerant during war, to less tolerant during peace.

NOTES

1The American Occupation was headed by General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP).

2Koshiro, Trans-Pacific Racisms, 1999, 161.

3Green, Black Yanks in the Pacific, 90.

4Koshiro, Trans-Pacific Racisms, 1999, 159.

5Green, Black Yanks in the Pacific, 88, 100.

6Koshiro, 1999, 178. “Occupation Babies Embitter Japanese,” NY Times 11/6/1955, p. 37.

7“Occupation Babies Embitter Japanese,” NY Times 11/6/1955, p. 37.

8Koshiro, “East Asia’s ‘Melting-Pot’,” 476.

9Miscegenation within the Japanese territories was ardently debated throughout the imperial era and yielded mixed messages to Japanese living in the colonies. The government exhorted Japanese expats to preserve the purity of their own race by avoiding marriage or fraternization with native colonial subjects. But it also variously sought to quell regional anti-Japanese sentiment by encouraging policies, including miscegenation, that would promote racial inclusion and harmony. For discussion of the complex topic of racial politics in the Japanese empire, see Weiner, “Discourses of Race, Nation and Empire;” and Koshiro, Imperial Eclipse. For discussion of how Japan defined the parameters of Japanese subjecthood, see Oguma, A Genealogy of “Japanese” Self-Images.

10Russia was a noteworthy exception to this racial division. Not wishing to further antagonize Russia, whose friendship it recognized as indispensable to its success on the Asian mainland, Japan viewed Russians as ethnically and culturally Asian. For a discussion, see Koshiro, Imperial Eclipse; and Koshiro, “East Asia’s ‘Melting-Pot’.”

11Eurasian (of mixed European and Asian ancestry) signifies an individual with parentage from specific geographical regions rather than of specific racial backgrounds. For convenience and with full cognizance that this usage is non-inclusive, in this article I use the term Eurasian as a racial signifier for part-Japanese/part-Caucasian individuals only. Discussion of other Eurasians (Sino-Europeans, Korean-Europeans, etc.) in wartime Japan is beyond the scope of this article.

12Dower, War without Mercy, 5, 8.

13Brecher, Honored and Dishonored Guests.

14For perspectives on racial mixing in the Japanese territories, see Ienaga, Japan’s Last War; and Koshiro, Imperial Eclipse.

15On a much-reduced scale, interracial unions had also been a point of concern since the 1634 establishment of the Dutch colony on the island of Deshima. The mere existence of Western settlements in Japan since the 1850s seemed to presage outright colonial subjugation, a threat that Japan avoided by entering into unequal partnerships with its Western trading partners.

16The Dutch Learning movement was initiated, in part, by an autopsy performed by Sugita Genpaku in 1771, the same year that Norinaga wrote his Naobi no mitama 直毘霊 (The Rectifying Spirit).

17Gary P. Leupp, Interracial Intimacy in Japan, 136.

18Yamamuro, “Shisō kijiku to shite no jinshu,” 56.

19Ibid., 57.

20Ibid., 181-82.

21Though legally equal, Japan’s minority groups continued to be treated as racially, physically, and morally distinct from “true” Japanese.

22Ibid., 61.

23Fukuzawa positioned himself in solidarity with this chorus in his famous 1885 essay “On Leaving Asia” (Datsu-a ron 脱亜論).

24Ibid., 69.

25For a full discussion, see Berlinguez-Kono, “Debates on Naichi Zakkyo in Japan,” 8-22.

26Quoted in Helm, Yokohama Yankee, 138.

27Dower, War without Mercy, 222. Systemic legacies of the racial purity myth endured long after the war. In the 1990s, Japan continued to preserve the illusion of its racial purity by camouflaging the identities of women brought from elsewhere in Asia to become wives of Japanese farmers. It also continued to welcome Latin Americans of Japanese ancestry with the flawed expectation that their racial heritage would facilitate their assimilation into Japanese society.

28Apcar, Shibaraku: Memories of Japan, 20-21.

29It is critical to note in this context that Japan’s pan-Asian vision was predicated on assumptions of racial superiority in Asia, where it did proceed to institute racist practices against its colonial subjects. We must also recognize that Japan did not complement its absence of racial policies against Caucasians with legislation protecting them. Ironically, the extraterritoriality mandated by the unequal treaties precluded those who drafted Japan’s 1889 constitution from guaranteeing universal human rights as other contemporary constitutions did. Its constitution granted rights protections to Japanese subjects, but the rights of foreign residents would be determined by their respective diplomatic authorities (Tanaka Hiroshi, Zainichi gaikokujin, 61).

30Executive Order 9066 assessed threats against the U.S. on the basis of race rather than nationality, a position that was reversed later in the war. When Japan later accused the U.S. of torturing, maltreating, and forcing labor upon internees of Japanese ancestry, the U.S. rebutted that among those in question only Japanese citizens loyal to Japan fell under Japanese jurisdiction. Japan could make no demands concerning American citizens, regardless of their loyalty, or even demands concerning Japanese citizens loyal to the U.S. (Elleman, Japanese-American Civilian Prisoner Exchanges, 114).

31Komiya, “Taiheiyō sensō shita no ‘tekikokujin’ yokuryū,” 1, 4; Komiya, “Taiheiyō sensō to Yokohama no gaikokujin,” 345.

32Yokohama gaikokujin shakai kenkyūkai, Yokohama kaikō shiryōkan, eds. Yokohama to gaikokujin shakai, 49.

33Ibid., 173.

34Harris, Boku wa nihonhei datta, 20, 83.

35Tamura, “Being an Enemy Alien in Kobe,” 39; Utsumi, “Japanese Army Internment Policies,” 177-78.

36Duus, Tokyo Rose: Orphan of the Pacific, 55.

37Tomita, Dear Miye, 144.

38Yokohama gaikokujin shakai kenkyūkai, Yokohama kaikō shiryōkan, ed. Yokohama to gaikokujin shakai, 49.

39For a comprehensive study of interracial marriages during this era, see Leupp, Interracial Intimacy in Japan.

40Altschul, As I Record these Memories, 80.

41Helm, Yokohama Yankee, 41. With the notable exception of missionaries, whose occupational success hinged on their ability to forge friendly relations with local Japanese, most resident foreigners, including Eurasians, remained insulated from mainstream Japanese society. They tended to live, work, and recreate in close proximity, and send their children to international schools. Though some acquired enough proficiency in Japanese to communicate with their Japanese servants and staff, very few became literate in Japanese.

42Ibid., 170.

43Ibid., 174. What prestige the Helms lost in pedigree they redeemed with their generosity and deep roots in the Yokohama community.

44Balk, “An Outsider,” 396-97.

45Tomkinson was arrested by Occupation forces and tried for mistreatment of prisoners.

46For a detailed history of the Frank and Balk families during the war, see Brecher, Honored and Dishonored Guests.

47Eurasians in the camps who spoke Japanese formed closer relations with camp guards, who would use them to run errands and then reward them with food.

48Duer, The Diary of Sydengham Yeend Duer, 39.

49For a full discussion of this thesis, see Brecher, Honored and Dishonored Guests.

50Uyehara, ”My Story,” 30. I wish to thank Cecil Uyehara for sharing this manuscript.

51Duer, Diary of Sydengham Yeend Duer, 112.

52Ibid., 107.

53Ibid., 111.

54Ibid., 117.

55Testimonies indicate that children developed more hostility toward Caucasians than adults. Children were subjected to indoctrination in school and, one imagines, lacked the life experience to question anti-white state propaganda. (Brecher, Honored and Dishonored Guests.)

56In some but certainly not all cases, internment camps holding women afforded their inmates comparatively greater leniencies than male-only camps. Waterford writes that the 26 nuns at the Sendai camp, for example, “were never considered ‘real’ internees…. Their position as nuns was an uncomfortable one for the Japanese authorities, who were not used to guarding such a group of women.” (Waterford, Prisoners of the Japanese, 209).

57Morris, Traveller from Tokyo, 131, 143.

58Uyehara, ”My Story,” 34-40.

59Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 94-108.

60Koshiro, Imperial Eclipse, 54, 57-59.

61Ueda and Arai, Senjika Nihon no Doitsujintachi, 92; Helm, Yokohama Yankee, 73.

62Duer, Diary of Sydengham Yeend Duer, 55.

63For a discussion of the correlation between community solidarity and community resilience in Japan, specifically their ability to contend with disasters, see Aldrich, Building Resilience.

64Apcar, Shibaraku, 72.

65For one such story, see Minoru Kiyota, Beyond Loyalty.

66Most Nisei had been sent to Japan to study. The Japanese government, which equated Japanese citizenship with Japanese decent, revoked their U.S. citizenship but took no other action against them (Tomita, Dear Miye, 1, 14-15).

67Welty, “Multiraciality and Migration,” 171.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aldrich, Daniel P. Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Altschul, Heinz. As I Record these Memories…: Erinnerungen eines deutschen Kaufmanss in Kobe, 1926-29, 1934-46. Eds. Nikola Herweg, Thomas Pekar, and Christian W. Spang. Munich: Iudicium, 2014.

Apcar, Lucille. Shibaraku: Memories of Japan, 1926-1946. Parker, CO: Outskirts Press, 2011.

Balk, Estelle. “An Outsider: The Story of a European Refugee in Japan during World War II.” Unpublished manuscript, ca. 1947. Archival material. Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University.

Berlinguez-Kono, Noriko. “Debates on Naichi Zakkyo in Japan (1879-99): The Influence of Spencerian Social Evolutionism on the Japanese Perception of the West.” In The Japanese and Europe: Images and Perceptions, ed. Bert Edström. Richmond, Surrey [U.K.]: Japan Library, 2000, 8-22.

Brecher, W. Puck. Honored and Dishonored Guests: Westerners in Wartime Japan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2017.

Dower, John W. War without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. New York: Pantheon Books, 1986.

Duer, Sydengham. The Diary of Sydengham Yeend Duer: Being a Record of Life in a Japanese Civilian Internment Camp during World War II, ed. Edward Y. Duer. Unpublished manuscript, 2009.

Duus, Masayo. Tokyo Rose: Orphan of the Pacific. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1979.

Elleman, Bruce. Japanese-American Civilian Prisoner Exchanges and Detention Camps, 1941-45. London and New York: Routledge, 2006.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Press, 1967.

Green, Michael Cullen. Black Yanks in the Pacific: Race and the Making of American Military Empire after World War II. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2010.

Harris, James B. Boku wa nihonhei datta 僕は日本兵だった. Tokyo: Ōbunsha 大分社, 1986.

Helm, Leslie. Yokohama Yankee: My Family’s Five Generations as Outsiders in Japan. Seattle: Chin Music Press, 2013.

Ienaga, Saburo. Japan’s Last War: World War II and the Japanese, 1931-1945. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1979.

Kiyota, Minoru. Beyond Loyalty: The Story of a Kibei, trans. Linda Klepinger Keenan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

Komiya Mayumi 小宮 まゆみ. “Taiheiyō sensō shita no ‘tekikokujin’ yokuryū: Nihon kokunai ni sonzai shita eibeikei gaikokujin no yokuryū ni tsuite” 太平洋戦争下の「敵国人」抑留: 日本国内に在住した英米系外国人の抑留について . Ochanomizu shigaku お茶の水史学 (September 1999): 1-48.

_____. “Taiheiyō sensō to Yokohama no gaikokujin. 太平洋戦争. と. 横浜. の. 外国人 .” In Kanagawa no rekishi wo yomu 神奈川歴史を読む , ed. Kanagawa-ken kōtō gakkō kyōka kenkyūkai 神奈川県高等学校 教科研究会 . Yamakawa shuppansha 山川出版社 , 2007, 341-69.

Koshiro, Yukiko. “East Asia’s ‘Melting-Pot’: Reevaluating Race Relations in Japan’s Colonial Empire.” In Race and Racism in Modern East Asia: Western and Eastern Constructions, eds. Rotem Kowner and Walter Demel. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2013: 475-98.

_____. Imperial Eclipse: Japan’s Strategic Thinking about Continental Asia before August 1945. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013.

_____. Trans-Pacific Racisms and the U.S. Occupation of Japan. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Leupp, Gary P. Interracial Intimacy in Japan: Western Men and Japanese Women, 1543-1900. London; New York: Continuum, 2003.

Morris, John. Traveller from Tokyo. London: The Cresset Press, 1943.

“Occupation Babies Embitter Japanese.” New York Times. November 6, 1955: p. 37.

Oguma Eiji. A Genealogy of “Japanese” Self-Images. Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press, 2002.

Tamura, Keiko. “Being an Enemy Alien in Kobe.” History Australia 10:2 (2013).

Tanaka Hiroshi 田中宏 . Zainichi gaikokujin: Hō no kabe, kokoro no mizo 在日外国人 法の壁、心の溝 . Tokyo: Iwanami shinsho 岩波新書 , 1995.

Tomita, Mary Kimoto. Dear Miye: Letters Home from Japan, 1939-1946, ed. Robert G. Lee. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995.

Ueda Kōji and Arai Jun 上田浩二, 荒井訓 , Senjika Nihon no Doitsujintachi 戦時下日本のドイツ人たち . Tokyo: Shūeisha shinsho 集英社新書 , 2003.

Utsumi, Aiko. “Japanese Army Internment Policies for Enemy Civilians during the Asia-Pacific War.” Donald Denoon, Mark Hudson, et al., eds. Multicultural Japan: Paleolithic to Postmodern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp. 174-209.

Uyehara, Vera Eugenie. ”My Story.” Unpublished manuscript, Tokyo and Washington, D.C., 1956-1981.

Waterford, Van. Prisoners of the Japanese in World War II. Jefferson, N.C. and London: McFarland & Co., 1994.

Weiner, Michael. “Discourses of race, nation and Empire in Pre-1945 Japan.” In Race, Ethnicity and Migration in Modern Japan, Vol. 1, edited by Michael Weiner, 217-39. London; New York: Routledge Curzon, 2004.

Welty, Lily Anne Yumi. “Multiraciality and Migration: Mixed-Race American Okinawans, 1945-1972.” In Mixed Global Race, edited by Rebecca C. King-O’Riain, et al., 167-187. New York and London: New York University Press, 2014.

Yamamuro Shin’ichi 山室信一 , “Shisō kijiku to shite no jinshu” 思想基軸としての人種 (Race as an intellectual polarity), Shisō kadai to shite no Ajia: kijuku, renso, tōki 思想課題としてのアジア 基軸・連鎖・投企 (Asia as an intellectual problem: Axis, Chains, and Entwurf). Tokyo: Iwanami shoten 岩波書店 , 2001.

Yokohama gaikokujin shakai kenkyūkai 横浜外国人社会研究会, Yokohama kaikō shiryōkan, eds. Yokohama to gaikokujin shakai: gekidō no nijūseiki wo ikita hitobito 横浜と外国人社会―激動の 20世紀を生きた人々 . Tokyo: Nihon keizai hyōronsha 日本経済評論社 , 2015.