Volume XIV, No. 2: Spring 2017

Erasure, Solidarity, Duplicity: Interracial Experience across Colonial Hong Kong and Foreign Enclaves in China from the late 1800s to the 1980s

REFERENCES | AUTHOR BIO | ![]() Download this Article as a PDF file

Download this Article as a PDF file

When citing this article, please refer to the PDF which includes page numbers.

Keywords: Chinese Eurasian, Mixed Identities, Colonial Hong Kong, Interraciality, Racial Erasure, Eurasian communities

The history of Eurasians in Hong Kong and China is a very intricate and complex one involving conflicting treatment of social privilege, isolation, fascination, and suspicion, not to mention political dependence and exclusion. Attempts to erase mixed heritage were common. Solidarity emerged to fight off exclusion. In times of war, riots and revolutions, Eurasians often became targets of distrust; their face and mixed heritage made them liable to suspicion of duplicities and betrayal. The emotional and physical sufferings that many Eurasians endured as targets of criticisms in the decades of purges and revolutions were seldom recorded. To survive, many Eurasians resorted to silence, denial, self-censorship and ignorance about their mixed heritage. Attempts of conscious forgetting were needed for sheer survival and self-preservation.

The purpose of this essay is to look into the conflicting elements of erasure, solidarity and duplicity that were woven into the experiences of Eurasians and their families in Hong Kong and treaty ports such as Shanghai and Tianjin as well as other smaller foreign settlements like Chengdu, Beijing and Qingdao. Beginning in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the visibility of Eurasian offspring between Europeans (from different socio-economic strata like supervisors, clerks, policemen, soldiers) and Chinese women was becoming more apparent in Hong Kong. This condition was also happening in large treaty ports like Shanghai. At the same time, there was also a rise in the phenomenon of students returning home to China with their European wives and Eurasian offspring. The 1920s-30s saw a growing sense of Eurasian solidarity and communality in Hong Kong and to some extent, in other cosmopolitan treaty ports too. The Japanese Occupation and Chinese Civil War of the 1940s, witnessed the crumbling of the charmed and affluent world of the European and Eurasian circles. Strategic duplicities were needed to survive. The early post-war decades in Hong Kong marked the beginning of the diaspora of Eurasians away from Hong Kong to other western countries. Eurasians who lived in China during the Maoist years went through a series of reigns of terror when their Eurasian faces were seen as unwanted signifiers of racial and national humiliation from a bygone era.

This essay draws mainly from autobiographical writings by authors who grew up in both Hong Kong (e.g. Jean Ho Tung Gittins (何文姿), Irene Ho Tung Cheng (鄭何崎姿), Joyce Anderson Symons, Bruce S.K. Chan) and mainland China (e.g. Han Suyin [韩素音] aka Rosalie Chou [周月賓/周光瑚], Michael Kwan); family/extended family biographies (e.g. Polly Shih Brandmeyer and Eric Peter Ho [何鴻鑾]), newspaper articles, and government documents. Among the more recent scholarship on Eurasians that I shall engage is Anthony Sweeting’s article on “Hong Kong Eurasians” in Emma Teng’s edited volume Eurasians. As Sweeting passed away in 2008, his posthumous essay reflects his unfinished work on the development of Hong Kong’s Eurasian community. In this article, I hope to build on what Sweeting started. Teng’s richly-written Eurasians covers only up until the beginning of WWII. This essay shall build on that work by looking into Eurasian experiences from the 1940s to the 1970s covering the Japanese Occupation, the ensuing Chinese Civil War, the early Maoist Years and the Cultural Revolutions. While Teng’s Eurasians discusses the experience of Eurasian families in China in great depth with a strong focus on Shanghai, my essay also examines Eurasian experiences in a number of less-studied foreign settlements.

Unlike Eurasians in other parts of China, Hong Kong Eurasians had since the late 1800s taken up the important role of “middle man” between British communities and the Chinese population. As Hong Kong was a mercantile port and a crown colony, the relationship between the British and the Chinese communities was one that was mutually dependent economically and politically. Socially, however, the two communities were completely separate and indifferent to each other, with some occasional mutual ethnic contempt. A number of Eurasians like Ho Tung (何東) and Chan Kai Ming/George Tyson (陳啟明) had risen to very important public positions in the Legislative or Executive Council, Sanitary Board, and Chinese General Chamber of Commerce. Though Eurasians in other treaty ports played less of an intermediary role and oftentimes tended to blend and merge into the European environments, social snobbishness was still common. In contrast to Hong Kong, few Eurasians in other treaty ports served in public positions.

Another distinctive phenomenon in the Hong Kong Eurasian community was the practice of endogamous marriages – especially amongst the six or seven established Eurasian families. Marriage alliances between Hong Kong Eurasians and Eurasians from treaty ports like Shanghai were also common Teng has referred to this intermarriage practice between Eurasians in Hong Kong and others in Chinese coastal cities as the “endogamous web.”1 For example, Edith Sze Lin-Yut (施蓮玉)or Edith McClymont (1868-1964), wife of Ho Kom Tong (何甘棠), brother of Ho Tung, was a Eurasian from Shanghai. Joyce Anderson Symons (1918-2004) was a Shanghai-born Eurasian but grew up in Hong Kong. She married Robert Symons who was also a Shanghai Eurasian. The Andersons in Hong Kong maintained very close ties with other branches of the Anderson families in Shanghai. At the same time, many Hong Kong Eurasians were descendants from European merchants who worked in different foreign settlements in China. This included Thomas Rothwell (1831-1883), the British ancestor of Hong Kong’s Lo family, who was a tea merchant in Shanghai and had worked as a public tea inspector in Hankow. The German ancestor of the Shi family in Hong Kong, Adolf Zimmern (1842-1916), was a merchant in Shameen, Canton and Shanghai at different times.2 By virtue of generations of intermarriage and economic success as a mercantile community, the Hong Kong Eurasian community as a whole showed a much stronger sense of solidarity and community when compared to Eurasians in other foreign settlements in mainland China.

Late 1800s to early 1900s: Erasure and Denial of Eurasianness

In 1879, Sir John Smale, Chief Justice and Attorney General of Hong Kong, wrote that “No one can walk through some of the bye street...without counting beautiful children by the hundred whose Eurasian origin is self-declared.”3 Smale also wrote that “if the Government would enquire into the present conditions of these classes…in the great majority of cases the women have sunk into misery, and that of the children the girls that have survived have been sold to the profession of their mothers” and in the case of the boys, would “have sunk into the conditions of the mean whites of the late slave holding states of America…”4 In response to Smale’s concern about the rising number of Eurasian children living in poverty and neglect, the Governor had sought views on the issue from the Inspector of School, E.J. Eitel. He explained how there were in fact schools to take care of this class of Eurasian children such as the Government Central School. Eurasians boys from this school had obtained “good situations in Hong Kong, in the open ports and abroad.” At the same time, Eurasian girls “crowd into the schools kept by Missionary Societies.”5 Schools like Government Central School (later renamed Queen’s College), Diocesan Boys Schools (DBS), and the Diocesan Girls School (DGS) had very strong Eurasian alumni networks in Hong Kong. Similarly, in Shanghai, there was the Eurasian School established in 1870 (later renamed the Thomas Hanbury School in 1916)6 which also served the same purpose of educating Eurasian children “as nearly up to the European standard as possible.”7

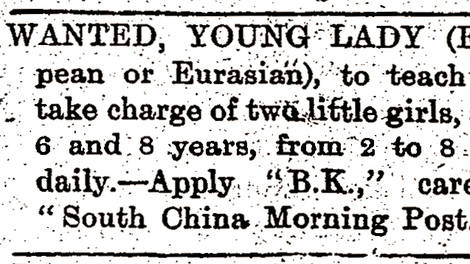

Eurasians with their bilingual abilities in both English and Chinese were much sought after as candidates in English-speaking jobs. Classified posts of “want ads” in the early 1900s asking specifically for Eurasians clerks, teachers, nurses, and storekeepers were common:

“WANTED. PORTUGUESE or EURASIAN CLERK. Must have knowledge of Bookkeeping” (1905)8

“WANTED a Young Portuguese or Eurasian GIRL for Store”(October 23, 1908)9

“WANTED, YOUNG LADY (European or Eurasian), to teach and take charge of two little girls”(September 24, 1908)10

“WANTED, Young Attractive GIRL, Portuguese or Eurasian; light labours and easy hours” (March 20, 1908)11

“$20 per month, FURNISHED Small Bedroom…Suitable for Portuguese or Eurasian.”(March 31, 1914)12

“YOUNG EURASIAN (20), just out of school seeks employment as Office Assistant. Speaks English fluently. Willing to start with moderate salary.”(March 26, 1914)13

Yet despite the high visibility of Eurasians in the city, official attempts to identify this ethnic group had not been successful at all. The official classification of Eurasians as an ethnic group of its own – a non-Chinese subgroup – had been quite futile, eventually leading to the erasure of this group in the official census. Beginning in 1897, Eurasians were categorized as a separate non-Chinese group. In 1897, the number of people that reported themselves as Eurasians was 272. The number dropped slightly to 267 in 1901, to 228 in 1906 and finally in 1911, only 42 people reported themselves as Eurasians.14 Despite the government readiness to recognize Eurasians as a separate ethnic group, members themselves had little intention to claim their Eurasianness. By 1921, the Eurasian category disappeared completely from the census.15

Hong Kong’s Registrar General remarked in 1901 that it was a very difficult matter to obtain the true number of the Eurasian population as the majority of Eurasians dressed in Chinese clothes and lived in a Chinese fashion, so would certainly identify themselves as Chinese.16 But perhaps an even stronger reason for the low response was that the term “Eurasian” was considered a “term of reproach.” The Cantonese in Hong Kong had a variety of derogatory terms to refer to a person of hybrid background, such as tsap chung (雜種 mixed breed), da luen chung (打亂種/messed up breed), and tsap ba long (雜崩冷 messed-up mixture) which suggested a kind of “genealogical abnormality.”17 As Carl Smith discussed, Eurasians in early colonial Hong Kong were often seen as “tangible evidence of moral irregularity” from both the European and Chinese communities.18

Hong Kong’s Registrar General remarked in 1901 that it was a very difficult matter to obtain the true number of the Eurasian population as the majority of Eurasians dressed in Chinese clothes and lived in a Chinese fashion, so would certainly identify themselves as Chinese.16 But perhaps an even stronger reason for the low response was that the term “Eurasian” was considered a “term of reproach.” The Cantonese in Hong Kong had a variety of derogatory terms to refer to a person of hybrid background, such as tsap chung (雜種 mixed breed), da luen chung (打亂種/messed up breed), and tsap ba long (雜崩冷 messed-up mixture) which suggested a kind of “genealogical abnormality.”17 As Carl Smith discussed, Eurasians in early colonial Hong Kong were often seen as “tangible evidence of moral irregularity” from both the European and Chinese communities.18

To escape the stigma of illegitimacy and moral laxity, many adopted the practice of changing their family names from the European surname to a Chinese surname as a way of erasing one’s mixed heritage. To survive and blend into the Chinese mercantile environment, some Eurasians – such as the Chan/MacKenzie family – sinicized their European family name. Bruce Chan explained how his grandfather, Chan Hong Kuey, changed his name from Mackenzie to Chan as “a strategy to escape the shame of illegitimacy. Nearly all the early Eurasians were offspring of common-law unions: there was no marriage and no birth certificate to ensure their legal status.”19 Common-law unions in Hong Kong simply meant two persons cohabiting without registering as husband and wife under the Hong Kong Marriage Ordinance.

Somehow, despite the different ethnic identities held by individuals or families, (i.e. some preferred to define themselves as Chinese through the use of Chinese surnames, other defined themselves through the use of their Western surnames) there was a strong sense of communal solidarity evident in business alliances, marriages, and lastly final resting places. This can be found in the formation of the Chiu Yuen Eurasian Cemetery (昭遠墳場) in 1897. Since the establishment of Hong Kong, the Colonial Cemetery was reserved only for Europeans, the Chinese Permanent Cemetery solely for the Chinese. Other ethnic groups, like the Parsis and Jews, formed their own burial grounds by the 1880s.20 In 1897, Sir Robert Ho Tung and his brother obtained a grant from the Government to establish a plot in Mount Davis as a Eurasian cemetery.21 Teng explains that “the founding of the Eurasian cemetery points to the emergence of an incipient sense of communal identity already in the 1890s.”22 Prominent members of Eurasian families – such as Halls and the Zimmerns – were all buried there. Interestingly, Ho Tung, the trustee of the Chiu Yuen, had preferred that he and his Eurasian wife Margaret Maclean (麥秀英) be buried in the Colonial Cemetery reserved for Europeans – a final ethnic shift after a whole lifetime of attempting to become more Chinese than the Chinese. This might have to do with the privilege of having finally gained access to a place that had been reserved for Europeans only, in the same way that he had in his life time violated the formidable Peak Preservation Ordinance which served to reserve the Peak for European residents only. Ironically, his own Chinese half-brother, who was of pure Chinese descent, took up “the choicest part of Mount Davis [in the Eurasian Cemetery] as his own private cemetery.”23

The practices of name-changing, endogamous marriages and cemeteries found in the Hong Kong Eurasian community were not as common in other foreign settlements in China. More often than not, Eurasians in foreign settlements in China took pride in their European family name. Most tended to merge into European circles. Hong Kong Eurasians, on the contrary, tended to downplay their Eurasian heritage in order to erase the stigma associated with illegitimacy vis-a-vis the “kept women system.”24 Eurasians in international settlements in China, however, were more diverse in their origins, coming from a wider spectrum of socio-economic strata. Apart from being offspring from liaisons between Chinese women and European soldiers, sailors and traders, many Eurasians as recorded in the memoirs and family biographies examined here were offspring of returning Chinese students and their European wives. In Hong Kong, there were few early records of returned Chinese students and their European spouses except for one: Kai Ho Kai. The famous barrister and physician Sir Ka Ho Kai (何啟, 1859-1914) returned to Hong Kong after his marriage to Alice Walkden of Blackheath (1852-84).25 After the death of his British wife, their Eurasian daughter was taken back to be brought up in England where her Eurasian heritage was conveniently and understandably erased in the British contexts.

As Teng has discussed, repeated prohibitions by the Qing Court against Chinese male students marrying foreign women had been unsuccessful. Interracial marriage was seen as deeply unpatriotic, as it represented the crime of “abandoning the ancestral land.”26 Marrying European women could also be seen as unfilial behavior. Chinese students who went abroad were mostly from wealthy gentry families and many were the brightest group of students who could have been aspiring Hanlin academicians. For example, several Chinese students from wealthy families – like Chou Yentung (周映彤, 1886-1958) and Charles Qian (1886-1920) of Chengdu, and Franking Tiam (1890-1919) and John Kwan (1889-1964) of Shanghai – returned from their studies with European wives. Though they all held important positions with the Government and/or foreign corporations upon their return to China, their marriages to European women were never fully accepted by their families. Nonetheless, their Eurasian offspring enjoyed a kind of socio-economic privilege that Eurasians in Hong Kong did not have. Eurasians from this kind of background were sometimes perceived as having “an elite aura.”27 The obvious reason was that it was only the privileged and affluent class who could afford to send their sons overseas. The return of Chinese students like Chou Yentung and Franking Tiam with their European wives and Eurasian children is described by Teng as “the early cohort of the new ‘modern phenomenon’ of mixed families.”28

Despite their socio-economic privilege, the ambiguous nationality status and racial identity of Eurasians in China had created difficulties for these families, especially in smaller foreign enclaves, such as consular stations like Chengdu, which were often under the governance of individual consuls. Han Suyin recalled how her Chinese father, Chou Yentung told his Belgian wife in 1913 in Chengdu:

My children would belong nowhere. Always there would be this double load for them, no place they could call their own land, their true home. No house for them in the world. Eurasians, despised by everyone…We must not have any more children.29

Chengdu was not exactly a hospitable place for the European wives and Eurasian offspring of Chinese returned students. The European population in Chengdu, mostly British and French missionaries and foreign consuls, was about 120 in 1907.30 Unlike the big cosmopolitan treaty ports along China coast like Shanghai and Tianjin, there were no foreign newspapers, or foreign banks. As discussed by Nield, dangers for foreigners in Chengdu steadily increased from 1911 with anti-foreign riots upon the announcement of new Hankow-Chengdu railway to be built by a foreign syndicate.31 Marguerite Denis (Chou Yentung’s Belgian wife, and Han Suyin’s mother) also lived in Chengdu around the same time, between 1911-14. Han recalled her Belgian mother telling her how curious crowds of Chinese would follow her sedan chair, shouting “A foreign woman, a foreign she-devil, let us see her big nose…”32

Chengdu was not exactly a hospitable place for the European wives and Eurasian offspring of Chinese returned students. The European population in Chengdu, mostly British and French missionaries and foreign consuls, was about 120 in 1907.30 Unlike the big cosmopolitan treaty ports along China coast like Shanghai and Tianjin, there were no foreign newspapers, or foreign banks. As discussed by Nield, dangers for foreigners in Chengdu steadily increased from 1911 with anti-foreign riots upon the announcement of new Hankow-Chengdu railway to be built by a foreign syndicate.31 Marguerite Denis (Chou Yentung’s Belgian wife, and Han Suyin’s mother) also lived in Chengdu around the same time, between 1911-14. Han recalled her Belgian mother telling her how curious crowds of Chinese would follow her sedan chair, shouting “A foreign woman, a foreign she-devil, let us see her big nose…”32

European women married to Chinese men and bearing Eurasian children in these inner settlements of China were often snubbed by the other European wives. When Chow Yentung worked along the Belgian-French Lunghai Railway, there was virtually no social contact between European wives of European engineers and European wives of Chinese engineers.33 The wives of Belgian engineers would not receive the wives of Chinese engineers.34 In other instances, they were described as women “who had committed the unpardonable sin for which there is no atoning.”35

Adela Warburton, wife of Charles Qian, and her daughter Elsie Qian returned to Chengdu from England in 1914. The experience of the this interracial family in Chengdu brought out the fact that despite British laws and regulations, prevailing prejudices against offspring of Chinese men and European women could complicate life in small consular stations in China. When Adela went to register at the British Consulate in Chengdu, the British Consul Wilkinson attempted to force the couple to Mixed Court to invalidate their marriage and return the wife to England on grounds of bigamy since Qian had been contracted to an arranged marriage when he was a boy.36 Adela by virtue of marrying a Chinese national had legally become Chinese and so did her children, even though her eldest daughter was born in England. She and her Eurasian children were refused registration by the British Consul in Chengdu. The irony was that Adela and Elsie actually sailed to China from London as British Subjects. By virtue of the rule of Jus soli, Elsie Qian was a British subject. Similarly, Han Suyin’s mother, Marguerite Denis, also had the same experience when she went to the Belgian Consul in Hankow in 1913 – a city besieged by violent anti-foreign sentiments as well as revolutions against Yuan Shikai. She was told that she was considered Chinese because she had married a Chinese and if anything happened to her, the Belgian government would not be held responsible.37

The Qians in midst of the political turmoil between the different military governors, left Chengdu for Shanghai in 1919 like most foreigners at that time. Unfortunately, Charles Qian, while still being Commissioner of Foreign Affairs, died in 1919. Adela took her Eurasian children to Shanghai. That same year, Adela gave birth to her youngest daughter in Shanghai and died from cholera soon after. The four Eurasian sisters suddenly found themselves orphaned and homeless in an unfamiliar province.38 The extended Warburton family in England probably could not arrange for the return of the Eurasian girls to a post-war England, especially when they were considered “Chinese.” None of the Chinese extended Qian family came forward to claim custody of the four young Eurasian girls. Finally the Warburton girls were taken in by missionaries.39 Elsie Qian, who was born in England and came to China as a British subject, had little choice but to remain in China as a Chinese and never left. With the anti-Western sentiments in new China in the 1950s and ‘60s, Elsie learned to “forget” her western language and British roots.40 And in many ways, through official interpretation of her race and nationality, and through the need for self-preservation and survival, her Eurasian heritage was erased consciously and subconsciously.

1920s and 1930s: Pride, Privilege and Solidarity

The 1920s and ‘30s marked a new era of emerging Eurasian pride and recognition. This was particularly evident in Hong Kong as reflected in the Hong Kong Government Census Reports. After the category of Eurasian was erased from the census in 1921, it was reinstated in the 1931 census. The number of people who reported themselves as Eurasians in 1931 was 837 – an increase of 20 times over the total 42 reported in 1911.41 This change reflected a new generation of Eurasians in Hong Kong who were offspring of marriages rather than the product of temporary cohabitations. They were not bothered by any stigma of illegitimacy as felt by the previous generations. This also signaled a new way of perceiving Eurasian identity collectively and individually by members of this community in Hong Kong. Over in Mainland China, it was reported in the South China Morning Post that mixed marriages were becoming more common in Beijing and Tianjin as racial biases abated. However, recognition and acceptance there of Eurasian offspring from mixed marriages was still slow in coming.

In Hong Kong, the formal institutionalization of a Eurasian community was expressed through the founding of The Welfare League (同仁會) in 1930. This charitable organization was formed by a group of prominent Eurasians “for the purpose of relief and succor of the needy in the Eurasian Community…”42 In his inaugural speech, secretary Charles Anderson proudly articulated the strong sense of ethnic pride as a Hong Kong Eurasian:

Gentlemen, Eurasians in distress have to turn to Eurasians for succour – the outsider is unsympathetic if not overtly hostile… it has been said of us that we can have no unity… is a challenge to be faced and an insult to be wiped out… They do not realize that, after all, there is no gulf between a Chan and a Smith amongst us and that underlying the superficial differences in names and outlook, the spirit of kinship and brotherhood burns brightly… We Eurasians, being born in this world, belong to it. With the blood of Old China mixed with that of Europe in us, we show the world that in this fusion, to put it no higher, is not detrimental to good citizenship…the Eurasians within the seven seas are some of the people sent into this world to assist in the accomplishment of this ideal. In this part of China, we are a force to be forced with, a force to be respected and a force to be better appreciated…”43

As Teng discusses, Charles Anderson asserts “a unitary Eurasianness” where there is “no gulf between a Chan and a Smith.”44 The phrase “We Eurasians” expressed a celebration of a strong sense of solidarity and pride. That mixed heritage should no longer be a kind of family shame or secret is recalled by a number of Eurasian memoirists, such as Irene Hotung Cheng, Eric Peter Ho and Bruce Chan/Mackenzie.45

Yet, as recorded by Eric Peter Ho, its President, the League’s “lament” throughout its history continued to be the “short membership list” which had probably to do with the reluctance of some members to identify themselves as Eurasians in public.46 Joyce Anderson Symons, daughter of Charles Anderson, recalled how her father had named four leading Hong Kong personalities “all secretly members of the League but who were publicly Chinese.” The “duplicity” of some of its members continued to be an embarrassment within this official establishment of Eurasian solidarity.

A few years after the founding of the Welfare League, this sense of solidarity and benevolence for people of mixed heritage was expressed again by the doyen of the Hong Kong Eurasian community, Ho Tung – this time, not just for Eurasians in Hong Kong, but Eurasians in England, the “fatherland” of many Hong Kong Eurasians. With financial support from Ho Tung, the Chung Hwa School & Club was established in Pennyfields, East London for the education and employment of Eurasian children in London. Ho Tung bought a three-story house big enough to accommodate 100 Eurasian children. These children, who “often have to act as interpreters between their fathers and mothers, as the fathers speak little English and the mothers no Chinese,” were given education on Chinese language and culture.47

The sense of Eurasian solidarity and communality seen in Hong Kong was not as strongly felt in other foreign settlements in China. This was probably because Hong Kong Eurasians had, as mentioned earlier, been practicing endogamous marriage for three to four generations by the 1920s and 1930s. Eurasians in other parts of China, particularly larger treaty ports like Shanghai, Beijing and Tianjin, tended to merge into the European communities, rather than forming their own. As I touched on previously, while mixed marriages in 1930s Beijing and Tianjin were slowly gaining acceptance, the recognition of their Eurasian offspring was much slower. In a 1935 article from The South China Morning Post entitled “Mixed Marriages,” the author notes that:

The crumbling of old outworn racial hatred is resulting in an increasing number of mixed marriages between East and West. Records show that despite Kipling large numbers of lovelorn couples are willing to meet each other half way, at least, and make a serious effort to find connubial bliss, despite the differences in colour, creed and background… The social stigma attached to the Oriental-Occidental marriages has almost completely disappeared from both Chinese and foreign circles in most sections of China, although the offspring of such unions find recognition much slower.48

The article also identified the increasingly common phenomenon of mixed marriages between Euro-pean men and Chinese women and between returned Chinese (male) students and European women:

Chinese who attend universities in the United States or England frequently return with American or English wives. Even in the small American colony of Tianjin there are at least a half dozen Americans, including a college professor, newspaper correspondent, engineer and businessman with Chinese wives. At least four Chinese graduates from American universities are married to American girls.49

The social stigma attached to Eurasian offspring of mixed marriages, however, had yet to be worn down. In this same article, it was reported that the American wife of a Chinese man in Beijing had gone to the extreme of deciding not to have any Eurasian children, “so she told her husband to have children by a [Chinese] concubine and she would adopt and raise them as her own.” 50

In Herbert Lamson’s 1936 study on “The Eurasian in Shanghai,” he argued that Eurasians in the city were people who tended “to look down upon the native side” of their ancestry and resist “assimilation to native ways and loyalties.”51 This critical view of Shanghai Eurasians was evidenced by Joyce Anderson’s own experience. She recalled how in 1937 her Shanghai relatives fled the embattled city for Hong Kong, and foreign nationals began to flee China. After staying with the Andersons for a while, her Shanghai Eurasian relatives observed that they – the Hong Kong Eurasians – treated “the Chinese” far too well.” 52

Both Michael David Kwan and Han Suyin recalled the attitudes of Eurasian friends in Beijing and Tianjin in their memoirs. Some of the Eurasians depicted in their writings resonate with Lamson’s discussion of Shanghai Eurasians. Kwan’s Eurasian childhood in the 1930s Beijing Legation Quarter and Tianjin British Concession seemed to merge naturally with other European and American circles in the environment. As a child Kwan went to an American International School where his playmates were Americans and British. He said “We lived a charmed life in 1938. While the Japanese overran much of north China, the Concessions under foreign protection were out of their reach…”53

Leading a privileged life in North China during the 1930s where his social circle mainly consisted of privileged Eurasians like himself, Kwan elucidated the unspoken hierarchy of Eurasians in his socio-economic strata. At the top of the ladder was “the crème de la crème” -Eurasians with legal European surnames who adopted western customs. These were the offspring of marriages between European men and Chinese women. However, they “saw themselves as being a cut or two above the natives.”54 Then came the group with European family names who were offspring from unwed unions between European men and Chinese women. Without legal right to western surnames, this group Kwan referred to as “hyphens” like his uncle George Findlay-Wu. “In their eagerness to play down their Chinese side, they often adopted exaggerated western attitudes and became the worst snobs and bigots.”55 Interestingly, compared to their counterparts in Hong Kong, Eurasian offspring of unwed mixed couples in Hong Kong tended to enhance and identify strongly with their Chinese side rather than their western one.

Lamson was quite critical of both the groups with European family surnames, and labeled them as a class of Chinese-despising hybrids. Han, who grew up in 1920s and ‘30s Beijing, remembered a Eurasian girl in her family’s social circle whom she believed was “less” of a “half-caste” because her father was a Greek doctor and she had a European surname. Her Chinese mother was “kept hidden in the house” away from the social scene so as not to affect her prospect of securing a good marriage. The girl, as Han recalled, was eventually able to marry a French clerk who worked in the French bank.56

Kwan as a child had lived with his uncle George Findlay-Wu’s family in the international settlement in 1930s Tianjin. Findlay-Wu was the son of a wealthy Scottish man descended from a family of distillers, and his Chinese mother was the daughter of a Chinese merchant. They were never wed. The Findlay-Wus lived in a Tudor-style house on Lambert Road in the British Concession of Tianjin. It was “an English household” with “not a vestige of China in the house.” Chinese language was banned and the servants had to speak pidgin English.”57 Their son, Kwan’s uncle George, married a British woman named Hester, who objected to their daughter dating a Eurasian boy called Robert Wong. Even though Robert was Eurasian like her daughter, he was a Eurasian with a Chinese surname. Robert’s father, like Kwan’s own father, was a returned Chinese student from Cambridge who had married a British wife.58

Kwan considered this group of Eurasians like Robert Wong and himself – Eurasians with Chinese surnames – as “the lowest rung on this social ladder.” Kwan added in a somewhat self-deprecating tone, “people of mixed blood with Chinese surnames were considered Chinese by everyone except other Chinese.”59 Kwan’s own experience in Eurasian/European circles – as well as in his own awkward encounter with his own paternal Chinese extended family in Shanghai – calls into question Lamson’s assertion that Eurasians with Chinese fathers were more acceptable in the “Chinese cultural milieu” than those with European fathers.60 When young Kwan first arrived at the his father’s extended family home in Shanghai, he was told by his Uncle Thirteen that “as a rule Mother [Kwan’s Chinese paternal grandmother and the matriarch of the Kwan family] does not allow foreigners in the house.” He told his nephew “We will converse in Chinese.”61

Despite the stigma against Eurasians in the 1920s and 1930s Beijing, Eurasians did enjoy certain monetary privileges in their employment at foreign companies. Though not accepted as being equivalent to European, Eurasians placed far above the Chinese in the corporate ladder salary scale. Han’s brother, George Chou (周子春), worked for a German Bank in 1925 as a Eurasian bank clerk. His salary was three times that of a Chinese clerk, who did exactly the same work and had been doing it for twenty years. But he was earning only one-fifth the salary of a young German boy at the firm. Seeing himself as a victim of the racial hierarchy, George told his sister somewhat indignantly that the German boy could not even spell German words properly.62

The Eurasian world in Beijing during this time as described by Han Suyin was a “half-world, so cheerful and self-satisfied with small conceit” and “clinging to the arrogant white world whose dominion and privileges in Asia were never questioned (except by the Chinese, but they did not count in this small half-world of ours).”63 Most of the secretaries in the office of the Beijing Union Medical College (PUMC) were European or Eurasian girls who either came from Tianjin or Shanghai, or had been trained there.64 Han joined PUMC as a young typist at the Rockefeller Center in 1930. Eurasians were grouped less by family name than by nationality in the institutional pay scale. When her Eurasian colleague Hilda Kuo’s application for naturalization as a British subject came through, Hilda was entitled to European pay as an English national.65

Amongst this group of young Eurasian clerks and secretaries a sense of communality could be felt. They congregated at the French Club in the Legation Quarters with its skating rink and tennis courts as well as at music evenings at the German Club. They were conscious of the fact that they were socially above the Chinese and had access to places where Chinese were not allowed or might not have access. They were also conscious of how their Eurasian phenotypes could unintentionally draw amorous admiration, desire and jealousy. Han recalled how Chinese warlords and Manchu princes would bring along their Eurasian mistresses to parties and balls. She herself, as a junior secretary, had to fend off amorous advances from colleagues and put up with suspicious looks from the European wives of senior colleagues. Han and Fredi Jung, a German Eurasian clerk who was her PUMC colleague in the accounts department, were acutely aware of how Eurasian boys and girls were perceived – a stigma associated with the privilege of being above the Chinese, which was not easy to shake off. Fredi said “many Eurasian girls were brought up to think that going out with a white man was an honour.”66

As mentioned, the recognition of their Eurasianness was also formalized in the institutional pay scale. A European secretary would normally earn $350 per month, while a Eurasian secretary earned $120 a month. Han herself, who had neither a European last name nor a foreign passport, began at $35, and reached $70 after two years. A Chinese clerk with ten years’ experience earned only $35. The goal of many Eurasian secretaries and clerks was to cross the Eurasian line and edge closer to the European pay scale.67 The privileged world so cherished by Han Suyin’s generation came to an end with the Japanese Occupation in Hong Kong and China – as did their sense of privileged solidarity.

Japanese Occupation and Civil War (1940s) – Neutrality and Duplicities

During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong and international settlements in China, Eurasians’ ambiguous status experienced a new phase. Eurasians were classified as one of the sub-groups under “Third Nationals” – mixing with the Axis group. Because of their racial hybridity, Eurasians were assured a kind of political neutrality. They were officially grouped as “Third Nationals” or “Neutrals” in Hong Kong and in China. Joyce Symons recalled how her father had to go to a counter at the Hongkong & Shanghai Bank (which had been commandeered by the Japanese) to “a strange section called ‘Third Nationals,’ a bureau which served Indians, Portuguese and Europeans from neutral or Axis states.68

During the run-up to the war in Hong Kong, some Eurasians changed their European surnames to Chinese ones to escape being pressed into the defense force. Joyce Symons saw the name-changing tactic as a cowardly act.69 Other Eurasians, like Jean Hotung Gittins (1908-95), went the other direction, changing her maiden name to become more European. Jean Hotung married Bill Gittins, a more Westernized Hong Kong Eurasian who went by his European surname. In order to ensure her ability to join her Hong Kong University European colleagues at the Stanley internment camp, Dr. Selwyn Clarke, the Hong Kong Director of Medical Service, advised her to take the precaution of changing her name slightly. Instead of Mrs. W.M. Gittins, she became Miss Jean Gittins on the University Relief Hospital staff list. The British name “Gittins” now appeared as her maiden name instead of “Hotung” – rendering her more European and therefore, justifying her admittance to the Stanley Camp. Other Eurasians, like her own sister-in-law, Irene Gittins Fincher, told Emily Hahn, “I’m Eurasian…I won’t go where I’m not supposed to.”70 Jean Hotung Gittins had also arranged for her two young Eurasian children (who were five and eleven years old) to go to Australia under the Evacuation Order from Whitehall. With an English family name and with their Caucasian phenotypes, the two children managed to pass as “pure” Europeans for the purpose of evacuation. Others were not so fortunate. At the July 1940 Legislative Council Meeting in Hong Kong, it was reported that some Eurasian evacuees who were “not of pure British descent” were “weeded out” in Manila by Government officials and returned to Hong Kong.71

During the battle of Hong Kong in December 1941, there was an all-Eurasian unit in the Hong Kong Voluntary Defense Corps (Company No. 3) which included Donald Anderson, the brother of Joyce Anderson, and Bill Gittins, the aforementioned husband of Jean Hotung. The unit suffered tremendous losses, “having lost all its officers and 70% of its men” by the time of its surrender on Christmas Day.72 British field officer Lieutenant Bevan Fields recalled how he was “impressed by the fine spirit and steadiness shown by the volunteers under my command… They were all Eurasians, most with a British father and a Chinese or Eurasian mother, a type which in Hong Kong had not been credited generally…”73

Unlike the Chinese in Hong Kong who could return to their village in China or British civilians who could evacuate to Australia, the Eurasians were the only community who had no other home. They stayed and “stood their ground against the invaders with conspicuous bravery.”74 Indignation was expressed in a letter to the editor of the South China Morning Post concerning how young Eurasian soldiers were treated, “but one thing is assured him, even if his mother is excluded from the registration for evacuation…he will be given permission to fight and die for his father’s flag.”75

The Japanese government, however, had found the Eurasians who could speak both Cantonese and English useful candidates for their intelligence service – and a living embodiment of their propaganda for racial unity in Asia.76 M. K. Lo, a prominent Hong Kong Eurasian (son-in-law of Ho Tung), was apprehended and kept in solitary confinement until he agreed to join the new government.77 Victor Needa, a Eurasian jockey who was the son of a Dutch father and Japanese mother, had grown up speaking Japanese in his hometown of Qingdao before coming to Hong Kong.78 He was remembered by Hahn as a “blessing” to the international circles and was able to save “the civilians from worse indignities because of his knowledge of Japanese speech…”79 His Japanese blood “which had meant so much misery before” later became a source of liberation and “occasional exaltation.”80 The Japanese Army and Navy treated him very well . He later became a “flourishing merchant” by collecting iron, bronze and aluminum for the Imperial Japanese Navy.81

The political loyalties of Robert Ho Tung, the doyen of Hong Kong’s Eurasian community, also came under question during wartime. During the pre-war years, Ho Tung had shown himself as a trusted citizen of the British Colonial government and was knighted by King George V in 1915. He had presented a warplane to the Chinese government and a couple of fighter planes to Britain’s Royal Air Force to fight the Japanese.82 During the Japanese occupation, he stayed in Macau for most of the time but managed to travel to Hong Kong now and then. Philip Snow writes that a British employee of Dodwell & Company in Hong Kong recalled that at a dinner with the Japanese, Ho Tung had praised the Co-Prosperity Sphere and thanked “the conquerors for all they had done for China.”83 Another prominent Eurasian and member of Hong Kong’s Executive Council, Sir Robert Kotewall, was remembered in a number of memoirs as being duplicitous in his loyalties. After the surrender by the Hong Kong British Government in 1941, Kotewall quickly relinquished his British title and changed his name from Robert Kotewall to Lu Kuk Wo (羅旭龢). Invited by (Japanese) Lieutenant-General Sakai to the Rose Room of the Peninsular Hotel on January 10, 1942, Kotewall showed slightly more enthusiasm for the new Japanese authority than might be expected for one who held a British title before the war. He expressed his gratitude “that the Japanese Army had avoided harming the people of Hong Kong or destroying the city…” and assured the Japanese victors that he and his colleagues would “put all our strength in Hong Kong and to cooperate with the Japanese Army authorities.”84 He finished his speech with his famous “Banzai!” He also welcomed the arrival of General Isogai, and declared “on behalf of the Chinese community that the one and a half million people of Hong Kong shared in the reflection of the glory of the Imperial Army.”85 Kotewall was later made to resign from the Hong Kong Executive Council following which he retired from public life. After the war, a total of 28 people in Hong Kong were found guilty of collaborating with the Japanese – of which seven were “Europeans or Eurasians.”86

In Mainland China, the foreign protection enjoyed by international concessions in China came to an end during WWII. By early 1942, foreign nationals of Allied countries who were stranded in China were put into internment camps. Joyce Anderson’s sister, Marjorie Anderson, a British Subject from Hong Kong, was interned in the Lung Hwa camp in Shanghai. Joyce’s fiancé, Robert Symons, a Eurasian from Shanghai, was interned in the Yangchow camp in Shanghai.

The “charmed world” of Kwan’s childhood inside the Legation Quarter was shattered. Foreign nationals were rounded up for internment on a cold, blustery morning in January 1942. As a Eurasian in the Legation Quarter, young Kwan had to wear a white armband instead of a red armband like his British and American friends. Kwan remembered watching as his friends were being shoved onto trucks on that cold morning. He was the only one in the American International School who did not have to climb up into the truck – an uneasy privilege for an eight-year-old. Kwan watched as Buzzy, an older American boy, mouthed something at him which he could only decipher years later as “coward.”87 His Eurasianness for the first time had gained an uncomfortably duplicitous undertone.

With the departure of Americans and Europeans from the Legation Quarter, and the closing of the American school there, young Kwan had to transfer to a local Chinese school in Beijing. Kwan’s Eurasian phenotype from then on became an unwanted signifier of national and racial betrayal. The daily taunts and bullying Kwan experienced at the Chinese school reflected a deep-seated resentment towards anything foreign – including foreign blood in a person. This anti-foreign attitude was publicly encouraged by teachers. On one occasion, his teacher flicked his hair with her willow switch in front of the class:

“What color is it?” she sneered.

“The color of shit,” someone said from the back of the room… the teacher bared her teeth in a grin, and the tip of the stick travelled down my forehead to rest on the bridge of my nose.

“Yang bi zhi” she spat, and “Foreign nose” became my nickname.88

As the situation in Beijing worsened, the Kwan family moved to Qingdao in 1943 where he was enrolled in St. Michael’s School for Boys, a German missionary school. There he met a slightly older Eurasian boy called Shao who protected him from bullying by Chinese students. “I guess we’re birds of a feather,” Shao told Kwan. The writer reflected on how “members of a minority groups have uncanny ways of recognizing each other.”89 By the time the Japanese surrendered in 1945, the US Marines began arriving at Qingdao to assist the KMT in the disarmament of the Japanese. American servicemen filled the streets. Kwan recalled how the town welcomed the money brought in by the Americans. But there were also posters shouting “Yankee go home!” and “Down with Yankee imperialism!”90 A new anti-foreign tension took charge of the school with the death of the last European brother (a Corsican priest) during the war. The two Eurasian boys became daily targets in school for teachers and students to vent their anti-foreign sentiments. Political essentialism on racial mixture rendered young Kwan and Shao – both Eurasian children of Chinese fathers and European mothers – whipping boys for both teachers and students. In times of adversity, their mutual empathy and solidarity against daily vitriolic attacks on their racialized faces was a source of support. One day Brother Feng, a senior Chinese brother, came up to the two Eurasian boys and scrutinized them one after another:

Are you yang gwei zhi? – foreign devils – he asked in a gentle voice.

“We’re Chinese,” I replied.

He hauled me up by a handful of hair, so that I danced on tiptoes.

“What color is this?”

“Brown, sir.” I winced.

“Is it the proper hair color for a Chinese?”

“I don’t know, sir!”

He let go and I crumpled.91

Young Kwan went home and got a pair of scissors and cut his hair as close to the scalp as he could. His British mother was aghast at the boy’s determination to remove his brown fair hair – the cause of his daily misery at school. Kwan remembered how he felt when he looked at his own bald and blank-faced reflection in the mirror; it was a strategy not only to eliminate his racialized hair but a desire for anonymity and complete erasure of his mixed identity altogether – “Perhaps now I could disappear into the crowd.”92

His empathy for others like him did not stop with Shao. As American servicemen began to sail off back to America, Kwan also remembered seeing Chinese women holding Eurasian babies at the wharf.93 These were Eurasians of a different background facing a bleak and unknown future as the communist tightened their control on Qingdao. Kwan’s daily hell in the acutely xenophobic school came to an end when his father arranged for him on to leave for Hong Kong where he joined a British system school. When his father had earlier shown him a picture of the school, to his great relief he immediately identified a number of students who were Eurasians like he and Shao.

1950s-1970s – Living Reminders of Foreign Imperialism

Even though Hong Kong was a British Crown colony, the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s across the Chinese border spilled over into Hong Kong in form of protests and riots by workers and students. Bombs were left in different parts of the city with notes that read “Chinese comrades, stay away.” Anti-colonial and anti-foreign sentiments were running high. Europeans and Eurasians during times of riots and protests became convenient victims for radical Chinese patriots to vent their anger against foreign imperialism.

Even though Hong Kong was a British Crown colony, the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s across the Chinese border spilled over into Hong Kong in form of protests and riots by workers and students. Bombs were left in different parts of the city with notes that read “Chinese comrades, stay away.” Anti-colonial and anti-foreign sentiments were running high. Europeans and Eurasians during times of riots and protests became convenient victims for radical Chinese patriots to vent their anger against foreign imperialism.

Joyce Anderson Symons recalled how during the 1967 riots, taxi drivers would refuse to drive her even though she spoke Chinese. Dead rats were thrown into the gardens of her mother Lucy Perry and her sister Phyllis by “angry Chinese boys.”94 Eurasians became walking embodiments of imperialism for Chinese with communist leanings, and targets of their anti-colonial frustration. The riot years also marked the first wave of Eurasian (as well as Portuguese and Chinese) diaspora from Hong Kong to the US, UK, Canada and Australia – the first major brain drain for the city.

Across the border, the Cultural Revolution gained momentum. China’s door to the outside world was shut tight. Most foreigners left the country after 1949. Han Suyin’s Belgian mother and her Eurasian sisters managed to leave China via Hong Kong for Europe and eventually the US in the early 1950s. Michael Kwan’s British mother was able to leave for Hong Kong in 1948, eventually settling in Australia with her Chinese husband in the 1960s. But others chose to stay on. Gladys Taylor Yang was a British woman who married Yang Xianyi (楊憲益) after meeting him while studying at Oxford. The couple returned to the wartime capital of Chungking in 1940, where they became translators for the Foreign Languages Press in new China.95 The Yang family suffered tremendously in the following decades. When Han Suyin visited Gladys and Xianyi in the late 1950s, the couple did not wish to talk about the Hundred Flowers Movement, during which they were jailed as “counter-revolutionaries.”96 Gladys spent four years in solitary confinement during the Cultural Revolution, and their three children – a son and two daughters – were assigned to factories and work communes in the provinces. Their son Ye, who suffered from delusions about his racial identity, eventually took his own life.97

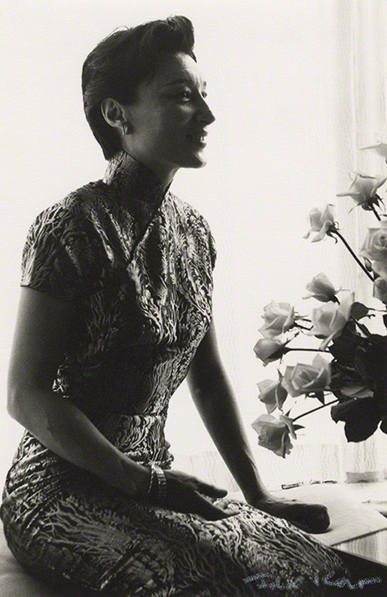

During the early post-war decades, Han Suyin herself was for a while suspected of duplicities, blacklisted and denied entry into the new China in the early 1950s. Yet, in the West, she was seen as an apologist and propagandist for the Chinese Communist Party.98 From the 1950s to 1970s, Han could not enter America except on a waiver. She had to apply to the State Department each time she wanted to go the US. (This despite the fact that her semi-autobiographical novel, [Love Is] A Many-Splendoured Thing, had become a best-seller and major motion picture in the US in 1955.)99

During the early post-war decades, Han Suyin herself was for a while suspected of duplicities, blacklisted and denied entry into the new China in the early 1950s. Yet, in the West, she was seen as an apologist and propagandist for the Chinese Communist Party.98 From the 1950s to 1970s, Han could not enter America except on a waiver. She had to apply to the State Department each time she wanted to go the US. (This despite the fact that her semi-autobiographical novel, [Love Is] A Many-Splendoured Thing, had become a best-seller and major motion picture in the US in 1955.)99

Despite her almost unabashed devotion to communism and praise for the communist system in her autobiographical writings, Han had great indignation towards the treatment of Eurasians in new China. In the last volume of her autobiography Han Suyin tracked down her Eurasian friends and their families. Not only were Eurasians targets of criticism, but the Chinese relatives of Eurasians had also suffered because of suspicions of “foreign connection.” Her own cousins in Sichuan suffered because of their connection with “foreigners” (meaning Han Suyin). One of her cousins was “grilled and grilled for weeks, accused of having illicit connections abroad and accused of having passed secrets…” His salary was cut and all his winter clothes were confiscated.100

The experiences Han records were mostly of Eurasians like herself with Chinese fathers who were descendants of wealthy gentry class. These Eurasians had strongly identified themselves as Chinese. But the European heritage written on their faces became a form of self-incriminating evidence, despite their utter devotion and contribution to the “new” country.

During one of her visits back to Beijing, Han also ran into her Eurasian school friend from the French Convent School in Beijing. Sophia Liu Hualan was a Eurasian with a Chinese diplomat father and a Polish mother. Despite the fact that all external ties outside China were cut in the 1950s and 60s, Hualan and her siblings were called traitors, accused of “collusion with the outside” and having “illicit connection with foreigners.”101 Like many intellectuals, Hualan suffered from a nervous breakdown after the Hundred Flowers Movement and the subsequent Anti-Rightist campaign. Like many others, she was subjected to house searches. Han described how Hualan and her siblings “…were entirely Chinese in feeling, although they did not look Chinese…”102 Hualan’s brother was in charge of airplane engines at the airport. He was dragged to so many meetings that he exhibited signs of mental imbalance. Other relatives were not as fortunate. Two committed suicide after they were beaten in front of Hualan. One day in 1966, as Rosalie and Hualan were walking along a street in Beijing, a young boy of about six or seven years old, playing with his little friend, saw the two Eurasian women. The kids shouted “Foreign devil!” As the women were both born and raised in China and spoke perfect Chinese, it was a term which neither had heard for a long time.103 Once again, this feeling of being an outsider in the city where one had grown up re-surfaced. When Han told a Chinese communist friend about the incident, she replied “That’s the fault of the people who do not integrate.” “But how can one integrate one’s looks? How can one become anonymous and merge totally when one’s nose and eyes and hair are different?”104

Han also tracked down another Eurasian childhood friend, Simon Hua. His father was a close friend of Han’s father; both were Chinese returned students who had studied engineering in Europe. Hua’s mother was French. Simon was a true communist even as a young boy studying in Beijing. He had voluntarily returned to Beijing from Paris in 1951. He, like other intellectuals and bourgeoisie were labeled as a “rightists,” and went through labor re-education.105

One could argue that the sufferings of Han’s Eurasian childhood friends were a result of their former privileged bourgeoisie background. However, the case of the Lu brothers demonstrates that Eurasians, even those with a working-class background, experienced equally harsh if not worse treatment during the Maoist years, beginning with Anti-Rightist Campaign and the subsequent Reign of Terror under the Red Guards. David Lu (b. 1944) and Brian Lu (b. 1946) were not the offspring of elitist returned students, but the children of a Chinese seaman who worked for P&O and a working-class British mother from Liverpool. The boys were taken back to Shanghai in 1947 to learn Chinese customs and traditions. Soon after their arrival, China closed its doors to the world. In the years of turmoil leading to the Great Leap Forward in 1958, the brothers, living with their fishermen relatives, were denounced, despite their young age, as “reactionary elements” and “English ghosts” with their light-colored skin and eyes. During the Cultural Revolution, their mixed heritage made them constant targets of suspicion. “On several occasions, during rampages by the Red Guards, the brothers were forced to hide in caves on a neighboring island until the witch-hunt abated.”106 Their birth certificates and letters from England were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution since any evidence of foreign ties would lead to punishment.107 Though the European heritage on their faces was something they could not destroy nor deny, it was yet evidence enough to subject them to severe punishments.

Conclusion

The ambiguous racial status of Eurasians had confounded administrative systems, policies and authorities such as the census bureau, consulate officers, evacuation officers and Chinese school teachers with their parochial ideology towards hybridity. Given the varying perceptions of Eurasianness and assumptions of hybridity in different sociopolitical contexts at different times, Eurasians had, as a strategy for survival, resorted to various forms of ethnic shift and ethnic erasure. Their voluntary ethnic changes reflect the agency that Eurasian individuals displayed through personal choices in the vicissitudes of events during this period of modern China.

The ethnic orientations of Eurasians in Hong Kong and those in other European enclaves very often leaned toward very different, if not opposite, directions. Eurasians in Hong Kong were more ready to identify themselves with the Chinese populations through name-changing. However, through their practice of intermarriage within the Eurasian endogamous web – they had consciously or unconsciously maintained and even celebrated their common mixed origins. But Eurasians in treaty ports tended more often to hold onto their European surnames and preferred to merge into the European circles and marry Europeans. By the 1920s and 1930s, Eurasians communities in both Hong Kong and other foreign enclaves had grown substantially compared to the earlier generations

Mixed marriages were more common. In some cases, recognitions of their Eurasianness was institutionalized. The world of Eurasian bourgeoisie, as recorded in some memoirs, was one of great social and economic privilege. However, during times of uncertainty, social and economic privilege were no longer recognized. As the Pacific war grew imminent, indignation was shown over the injustice for Eurasian soldiers who volunteered to fight in the war while their families were denied evacuation. The Japanese Occupation had flattened out all ethnic hierarchies in Hong Kong and other treaty ports. Eurasians, because of their uncertain racial status, were labeled as “Neutrals” or “Third Nationals.” They were oftentimes sought out to participate in the Japanese administration. The end of the Pacific War marked the resumption of the Chinese Civil War. Chinese populations in many major cities had become ever more xenophobic towards anyone who looked Western. By the late 1940s, most Eurasians as well as Europeans had left China. Many came and settled in Hong Kong before migrating to the West. For those left behind, life during the Maoist years inside China had been excruciatingly difficult. Their very faces were living reminders of foreign imperialism and national humiliation of a previous era. They become convenient and visible targets for political criticisms.

Han Suyin claimed that by the 1970s in China, there were only a few hundred Eurasians – “China’s smallest minority.”108 However, one last surviving member of the early 20th-century Eurasian communities in China had not been forgotten: Martha Clara Maasberg, the grand aunt of Eric Ho. Martha was a German Eurasian married to Walter Roberts, a Hong Kong Eurasian who died in the 1920s.109 Martha had lived alone in Shanghai for decades, witnessing the two world wars and the subsequent revolutions and purges. She was, as described by Eric Ho, the oldest British resident in China – or probably the oldest Eurasian in China. When the Queen Elizabeth II visited China in 1986, she had tea with Martha110 – a royal recognition of the hybrid community of a lost era.

NOTES

1Emma Teng, Eurasian: Mixed Identities in the United States, China and Hong Kong, 1842–1943. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 237.

2Eric Peter Ho, Tracing My Children’s Lineage. (Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong, Centre of Asian Studies, 2010), 196.

3Tony Sweeting, “Hong Kong Eurasians,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Hong Kong Branch, Vol. 55, (2015), 235.

4Ibid., 235

5David Pomfret, Youth and Empire: Trans-Colonial Childhoods in British and French Asia. (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2016)

6“Eurasian School – Report.” North China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette (1870-1941); June 1, 1872. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chinese Newspapers Collection, 431.

7Teng, Eurasian, 147.

8“WANTED &c.” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), August 5, 1905, 3.

9“WANTED ADS” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), October 23, 1908, 11.

10“NEW ADS” South China Morning Post (1903-1941) September 24, 1908, 3. http://search.proquest.com/hnpsouthchinamorningpost/docview/1754393635/fulltextPDF/FA6AB900E5F146B1PQ

11“WANTED ADS” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), March 20, 1908, 3.

12“Prepaid Advertisements” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), March 31, 1914, 5

13“NEW ADS” South China Morning Post(1903-1941) May 26, 1909,5.

14Hong Kong Sessional Papers. Hong Kong Census Reports 1897, 1901, 1906, 1911, 1921, 1931.

15Hong Kong Census Report 1921, 151.

16Hong Kong Census Report 1901, 4.

17Vicky Lee, Being Eurasian: Memories Across Racial Divides (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004), 18.

18Carl Smith, “Protected Women in the 19th Century Hong Kong,” in Women and Chinese Patriarchy: Submission, Servitude and Escape, ed. M. Jaschok and S. Miers (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1994).

19Bruce Chan, “Confessions of a Cultural Chameleon, or the Tensions of being a Colonial Eurasian.” Presented at the Workshop entitled “Breaking the Silence: the Politics of ‘Mixed Experiences’” (York University, Toronto, March 26, 2003), n.p.

20Ko Tim Keung, “A Review of Development of Cemeteries in Hong: 1841-1950,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Hong Kong Branch, Vol. 41 (2001): 246-7.

21Eric Peter Ho, Tracing My Children’s Lineage (University of Hong Kong, Centre of Asian Studies, 2010), 336-337.

22Emma Teng, Eurasian: Mixed Identities in the United States, China and Hong Kong, 1842 – 1943 (University of California Press: 2013), 236.

23Frances Tse Liu, Ho Kom-Tong: A Man for All Seasons (Hong Kong: Compradore House Limited, 2003), 197.

24See Carl Smith’s “Protected Women in the 19th Century Hong Kong,” 221-237.

25G.H. Chao, The Life and Times of Sir Kai Ho Kai (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2000), 28.

26Teng, Eurasians, 68.

27Ibid., 199.

28Ibid., 66.

29Han Suyin. The Cripple Tree, 290.

30Polly Shih Brandmeyer, “Cornell Plant, Lost Girls and Recovered Lives: Sino-British Relations at the Human Level in Late Qing and Early Republican China,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Hong Kong Branch, Vol. 54 (2014): 109.

31Robert Nield, China’s Foreign Places: The Foreign Presence in China in the Treaty Port Era, 1840-1943 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2015), 67.

32Han Suyin, The Cripple Tree, 283.

33Ibid., 20.

34Ibid., 291.

35Bradmeyer, “Cornell Plant, Lost Girls,” 109.

36Ibid.,110

37Han Suyin, The Cripple Tree, 293.

38Bradmeyer, “Cornell Plant, Lost Girls,” 113.

39Ibid.,113.

40Ibid.,124.

41Hong Kong Census Reports 1921 and 1931. Hong Kong Government.

42Eric Peter Ho, The Welfare League: The Sixty Years 1930-1990 (Hong Kong: The Welfare League, 1990), 9.

43Ibid., 9.

44Teng, Eurasians, 234.

45Irene Cheng, “Intercultural Reminiscences,” in Frank Murdock and Ian Watson, ed’s. (David C. Lam Institute for East-West Studies, Hong Kong Baptist University, 1997), 1-3, 43; Ho, Tracing My Children’s Lineage, 8; Bruce Chan, “Confessions,” n.p.

46Ho, The Welfare League, 9.

47“Young Eurasians Education: Sir Robert Ho Tung’s School in London, Boon for the Poor,” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), January 12, 1935, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: South China Morning Post, 16.

48“MIXED MARRIAGES.” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), May 25, 1935, 14. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1759654898.

49Ibid., 14.

50Ibid., 14.

51Herbert Lamson, “The Eurasian in Shanghai,” American Journal of Sociology, Volume 41, Issue 5 (March 1936): 642-648.

52Joyce Symons, Looking at the Stars (Hong Kong: Pegasus Books, 1996), 21.

53Michael David Kwan, Things That Must Not be Forgotten: A Childhood in Wartime China (Long Grove, Illinois: Waveland Press, 2012), 19.

54Ibid., 20.

55Ibid.

56Han Suyin, The Crippled Tree, 347.

57Kwan, Things That Must Not be Forgotten, 22.

58Ibid.

59Ibid., 20.

60Teng, Eurasians, 153; Lamson, “The American Community in Shanghai,” PhD dissertation, Harvard University, (1935), 591.

61Kwan, Things That Must Not be Forgotten, 222.

62Han Suyin, The Crippled Tree, 427.

63Han Suyin, The Mortal Flower (London: Jonathan Cape, 1966), 150.

64Ibid., 134.

65Ibid., 145.

66Ibid., 198.

67Ibid., 145.

68Symons, Looking at the Stars, 27; Philip Snow, Fall of Hong Kong: Britain, China and the Japanese Occupation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 391.

69Symons, Looking at the Stars, 23.

70Emily Hahn, Hong Kong Holiday (New York: Doubleday, 1946), 102.

71Hong Kong Hansard 1940, Minutes of Legislative Council Meeting dated 25 July 1940.

72Clifford Matthews & Oswald Cheung, Dispersal and Renewal: Hong Kong University During the War Years (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1998): 232.

73Ibid.

74Snow, Fall of Hong Kong, 68.

75“Status of Eurasians,” South China Morning Post (1904-1941). ProQuest Historical Newspapers: South China Morning Post, July 16, 1940.

76E.W. Clemons, “Japanese Race Propaganda During World War II.” Proceedings of Conference on Racial Identities in East Asia, 25-26 November 1994, Hong Kong Division of Social Science, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. E.W. 218, 220; quoted in Lee, Being Eurasian: Memories Across Racial Divides. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004, 69.

77Jean Gittins, Eastern Windows – Western Skies (Hong Kong: South China Morning Post, 1969), 38; Lee, (2004), 70.

78Emily Hahn, China to Me: A Partial Autobiography (Philadelphia: The Blakiston Co.; London: Virago Press, 1944), 38.

79Ibid., 343.

80Ibid.

81Snow, Fall of Hong Kong, 120-1.

82Jan Morris, Hong Kong: Epilogue to an Empire (London: Penguin Books, 1988): 179.

83Snow, Fall of Hong Kong, 195.

84Snow, Fall of Hong Kong, 107.

85Hahn, China to Me, 329; Sweeting, “Hong Kong Eurasians,” 95.

86Endacott, 246; quoted in Sweeting, “Hong Kong Eurasians,” 97.

87Kwan, Things That Must Not be Forgotten, 156.

88Ibid., 100.

89Ibid., 113.

90Ibid., 149.

91Ibid.,146.

92Ibid., 147.

93Ibid., 200.

94Symons, Looking at the Stars, 67.

95Delia Davin, “Gladys Yang.” The Guardian, November 24, 1999.

96Han Suyin, My House has Two Doors, 252.

97Davin, “Gladys Yang.”

98Wang Xuding, “Of Bridge Construction: A Critical Study of Han Suyin’s Historical and Autobiographical Writings,” PhD Dissertation, Department of English, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1996, 3.

99Han Suyin, My House has Two Doors, 268.

100Han Suyin, Phoenix Harvest, 194.

101Ibid., 108, 239.

102Han Suyin, My House has Two Doors, 389.

103Han Suyin, Phoenix Harvest, 55.

104Han Suyin, My House has Two Doors, 390. Han had claimed that in her meeting with Chou Enlai in the early 1960s, he had spoken against Han chauvinism and condemned its manifestations, and that he would help Eurasians in China (391).

105Han Suyin, My House has Two Doors, 266.

106McElroy, “The Lost Boys,” May 28, 2002, 1.

107Ibid., 1.

108Han Suyin, Phoenix Harvest, 183.

109Peter Hall, In the Web (Birkenhead, England: Apprin Press, 2012). 109.

110Ho, Tracing My Children’s Lineage, 59.

Bibliography

Brandmeyer, Polly Shih. “Cornell Plant, Lost Girls and Recovered Lives: Sino British Relations at the Human Level in Late Qing and Early Republican China.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Hong Kong Branch, Vol. 54, 2014, 101-130.

Chan, Bruce S.K. “Confessions of a Cultural Chameleon, or the Tensions of being a Colonial Eurasian.” Paper presented at the workshop entitled “Breaking the Silence: the Politics of ‘Mixed Experiences,” held at York University, Toronto (Canada), March 26, 2003.

Cheng, Irene. Intercultural Reminiscences. Edited by Frank Murdock and Ian Watson. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Baptist University, 1997.

Chao, G.H. The Life and Times of Sir Kai Ho Kai. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press. 2nd Edition, 2000.

Clemons, E.W. 1994. “Japanese Race Propaganda During World War II.” Proceedings of the Conference on Racial Identities in East Asia, 25-26 November 1994. Hong Kong Division of Social Science, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Davin, Delia. “Gladys Yang.” The Guardian, November 23, 1999. https://www.theguardian.com/news/1999/nov/24/guardianobituaries

Gittins, Jean. Eastern Windows – Western Skies. Hong Kong: South China Morning Post, 1969.

Endacott G.B.A. Hong Kong Eclipse. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1978.

“Eurasian School – Report.” North China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette (1870-1941); June 1, 1872. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chinese Newspapers Collection page 431. http://www.cnbksy.com/login;JSESSIONID=0031fcbe-ae54-4fe5-8dee-dd19a5f6ea26

Hahn, Emily. China to Me: A Partial Autobiography. Philadelphia: The Blakiston Co.; London: Virago Press, 1944.

______. Hong Kong Holiday. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

Hall, Peter. In the Web. Birkenhead, England: Apprin Press, 2012.

Han Suyin. The Crippled Tree. London: Jonathan Cape, 1965.

______. A Mortal Flower. London: Jonathan Cape, 1966.

______. My House Has Two Doors. London: Triad Grafton Books, 1980.

______. Phoenix Harvest. London: Triad Panther, 1980.

Ho, Eric Peter. The Welfare League: The Sixty Years 1930-1990. Hong Kong: The Welfare League, 1990.

______. Tracing My Children’s Lineage. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong, Centre of Asian Studies, 2010.

Hong Kong Hansard 1940. Minutes of Legislative Council Meeting, 25 July 1940.

Hong Kong Sessional Papers. Reports on the Census of the Colony for 1897, 1901, 1906, 1911, 1921, 1931. Hong Kong Government.

Ko, Tim Keung. “A Review of Development of Cemeteries in Hong: 1841-1950.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Hong Kong Branch (2001). Vol 41: 241-280.

Kwan, Michael David. Things That Must Not be Forgotten: A Childhood in Wartime China. Chicago: Waveland Press, 2012.

Lamson, Herbert. 1936. “The Eurasian in Shanghai.” American Journal of Sociology, Volume 41, Issue 5 (March 1936): 642-648.

______. The American Community in Shanghai. PhD dissertation. Harvard University, 1935.

Lee, Vicky. Being Eurasian: Memories Across Racial Divides. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004.

Liu, Frances Tse. Ho Kom-Tong: A Man for All Seasons. Hong Kong: Compradore House Limited, 2003.

Matthews, Clifford, & Oswald Cheung. Dispersal and Renewal: Hong Kong University During the War Years. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1998.

McElroy, Damien. “The Lost Boys.” South China Morning Post. May 28, 2002.

“MIXED MARRIAGES.” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), May 25, 1935. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1759654898?accountid=11440.

Morris, Jan. Hong Kong: Epilogue to an Empire. London: Penguin Books, 1988.

Needa, Veronica. 2009. FACE: Renegotiating Identity through Performance. Appendix 1: Eurasians in Conversation – Veronica Needa interviews the Reverend Guy Shea – London, April 1997. MA by Practice as Research. University of Kent.

“NEW ADS.” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), Sep 24, 1908, 3. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1498737658.

Nield, Robert. China’s Foreign Places: The Foreign Presence in China in the Treaty Port Era, 1840-1943. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2015.

Our Own Correspondent. “YOUNG EURASIANS’ EDUCATION. Sir Robert Ho Tung’s School in London.” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), Jan 12, 1935, 16. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1759627352.

O. I. C. U., “CORRESPONDENCE. Status of Eurasians.” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), Jul 16, 1940, 7. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1764470503.

Pomfret, David. Youth and Empire: Trans-Colonial Childhoods in British and French Asia. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2016.

“PREPAID ADVERTISEMENTS.” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), Mar 31, 1914, 5. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1499108005.

Snow, Philip. Fall of Hong Kong: Britain, China and the Japanese Occupation. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Smith, Carl. “Protected Women in the 19th Century Hong Kong,” in Women and Chinese Patriarchy: Submission, Servitude and Escape. Ed. M. Jaschok and S. Miers. Hong Kong University Press, 1994.

Sweeting, Tony. “Hong Kong Eurasians,” 83-114 in Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Hong Kong Branch, Vol. 55, 2015.

Symons, J.C. Looking at the Stars. Hong Kong: Pegasus Books, 1996.

Teng, Emma. Eurasian: Mixed Identities in the United States, China and Hong Kong, 1842–1943. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013.

Wang Xuding. “Of Bridge Construction: A Critical Study of Han Suyin’s Historical and Autobiographical Writings.” PhD Dissertation, Department of English, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1996.

“WANTED, & c.” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), Aug 16, 1905, 3. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1498557399?accountid=11440.

“WANT ADS.” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), Oct 23, 1908, 11. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1498745133?accountid=11440.

“WANT ADS.” South China Morning Post (1903-1941), Mar 20, 1908, 3. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1498715670?accountid=11440.