Volume XIV, No. 1: Fall 2016

Walking the Walk, Talking the Talk: Narratives that Challenge HIV/AIDS Taboos in Japan

REFERENCES | AUTHOR BIO | ![]() Download this Article as a PDF file

Download this Article as a PDF file

When citing this article, please refer to the PDF which includes page numbers.

Abstract: Illness narratives of Japanese people living with HIV/AIDS (yōseisha 陽性者) are written, performed, and embodied in culturally patterned ways that aim to simultaneously protect the narrator from stigmatization and discrimination while fostering public engagement and discussion about HIV/ AIDS so that Japanese, whatever their HIV status, can ‘live positively together’. These narratives demonstrate the efforts of yōseisha to assert their normalcy as Japanese through self-presentation on one hand, but advocate for acceptance of diversity on the other by stating that they cannot speak for all yōseisha. To illustrate these points, written, spoken, and performed narratives were gleaned from participant observation of HIV/AIDS events such as the AIDS Bunka Forum (AIDS 文化フォラム) and accounts of life with HIV/AIDS published by Place Tokyo (ぷれいす東京), Japan’s foremost HIV/AIDS organization. Framing these narratives in terms of ‘flexible kata’(型) I conclude that, despite the various formats these narratives are communicated, they share a general narrative structure mediated by strategic disclosure and controlled settings that can be adapted to fit the individuals, the sponsoring organization, and the audience involved. Use of this flexible kata makes it possible for yōseisha to speak relatively candidly about HIV/AIDS as a domestic issue from a variety of perspectives even though it is often considered taboo because of its association with death and ‘deviant’ sex.

Key Words: Japan, AIDS, HIV, yoseisha, taboos, stigma, narrative, performance

‘Any given day, someone faces it.

Any given day, someone is informed they have it.

Any given day, someone makes the decision to live with it.

HIV—

A small, small virus in an electron microscope

This big shadow thrown into everyday life

It’s been 20 years1 since HIV/AIDS appeared in the world.

This book contains notes by people living with and affected by HIV/AIDS.

LIVING TOGETHER.

If you can find yourself in the sentences of this book,

We’ll be grateful.’2

— From ‘Living Together: Our Stories,’ a 2005 booklet about living with HIV/AIDS edited by Ikegami Chizuko and Ikushima Yuzuru of Place Tokyo, Japan’s first and most influential HIV/AIDS support organization. Translation by the author.

Introduction

HIV/AIDS in Japan

Japanese infectious disease specialists know the pathogen Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) as hito men’eki fuzen uirusu (ヒト免疫不全ウイルス). 3 Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, or AIDS, which is the syndrome caused by HIV, is known as kotensei men’eki fuzen shoukougun (後天性免疫不全症候群). However, both HIV and AIDS are referred to collectively by the general public by a katakana name derived from the English acronym AIDS – eizu (エイズ). The most common route of infection in Japan is through sexual transmission: male-male sexual contact constituted almost 70% of all cases in 2015, while heterosexual sex accounted for approximately 20% of cases.4, 5 General efforts have been made to prevent the spread of HIV since the first reported case in Japan in 1985: condoms are readily available; sterilization of medical equipment, screening of organ and blood donors, and heat treatment of blood products are standard practices;6 and HIV screening of pregnant women is mandatory.7 However, prevention efforts at the individual level (such as barrier use during sex and HIV testing rates among members of high risk groups such as Japanese men) have been adversely affected by problems stemming from conservative sex education programs and policies that ignore sexual practices that go beyond family building, general perceptions of HIV/AIDS as a “foreign” rather than domestic disease, the perception that HIV=AIDS and AIDS=death, and sexual morals in which women are expected to be chaste wives and mothers (who can thus be blamed for the nation’s poor sexual health if they deviate from these ideals) while there is some expectation that men engage in extramarital sex (and are less likely to be held accountable for polluting the body politic).8

Treatment of HIV/AIDS includes a strict regimen of anti-retroviral (ARV) medication prescribed by a physician. These are available to Japanese patients on the national health insurance plan. However, two key points must be made here. First, almost none of the members of the HIV negative general public I interviewed in 2011-12 knew there was medication for HIV. Rather, in the words of one male interviewee, “when you get eizu, you die.”9 The second point is that ARVs are expensive even with insurance and require registration of one’s HIV status to get the discounted rate. Furthermore, several people living with HIV/AIDS, or yōseisha (陽性者) I interviewed pointed out that professionals such as pharmacists can determine a yōseisha’s HIV status based on their prescriptions, and even medical practitioners make assumptions about their sexuality and behaviors based on their HIV status. Mr. T, for example, stated in an October 2011 interview that although he is now on good terms with his doctor, he was taken aback when he was diagnosed a few years prior because his physician followed his diagnosis with the comment, “Oh, so you must be gay, then.” In other words, newly diagnosed yōseisha are likely to think that they are going to die upon hearing their HIV diagnosis (a fear highlighted in narratives below) because few Japanese know about ARVs, and they are vulnerable to discrimination and stigmatization even by those who are supposed to help them once they are diagnosed and begin treatment.

Misconceptions about HIV/AIDS such as these may be at the root of HIV/AIDS incidence and prevalence in Japan: there have been about 25,000 cases of HIV/AIDS reported cumulatively (about 0.1% of the population)10. There are about 1,000 new cases of HIV and 400 new cases AIDS annually, and these new cases of AIDS represent people who were NOT previously diagnosed as having HIV (ibid). This phenomenon is called ‘suddenly, AIDS’ or ikinari eizu (いきなりエイズ). Although these numbers are much smaller than prevalence and incidence in other countries, the general upward trend is troubling for a society with a relatively high literacy rate and a socialized healthcare system. Those living with HIV/AIDS and working with yōseisha populations are interested in breaking these misconceptions about the illness by challenging the taboos surrounding it through direct discussion of HIV/AIDS in various narrative formats, discussed below.

Illness narratives: Forms and Uses

Researchers from disciplines such as literature, history, psychology, and anthropology have all discussed uses of illness narratives in some form, and each of those perspectives are useful for the discussion of HIV/AIDS narratives in Japan. Regarding narrative forms in general (both written and spoken), Ochs and Capps describe narrative as a method of making sense of experience through the ordering of events that may seem disparate; it is also a ‘resource for socializing emotions, attitude, and identities, developing personal relationships, and constituting membership in a community.11 They further assert that narrative and self are inseparable because narratives are born out of and give shape to experience.12 In other words, experience shapes narrative; but being able to order events through culturally appropriate narratives allows a person to assign meaning to an experience, serves as a mode of self-expression, and functions as an assertion or sign of one’s position in a community.

Narratives have been an anthropological staple since the early 1900s but W.H.R. Rivers’ use of illness narratives (spoken narratives converted to written format as ethnographic data) at that time was among the earliest to argue that the healing practices of others were not random but rather exhibited a coherent, internal logic.13 In this way, illness narratives have been considered ways of ‘finding out’ about cultural systems for the listener. In the same way that Rivers learned about Melanesian societies by studying massage there, we can learn about Japanese culture and concepts of illness through analysis of how the Japanese narrate HIV/AIDS. Additionally, it has become well-known that illness/wellness narratives are not medically inert for the writer-speaker or the reader-listener. In other words, narratives are not just about health practices – they can influence individual health by providing catharsis, and public health through audience education. Recognition of these benefits began with Freud, and is apparent in the work of psychiatrist-anthropologists Allan Young and Arthur Kleinman.14

An early example of this that is particularly germane to written illness narratives of infectious disease in Japan is historian Kathryn Tanaka’s analysis of leprosy/Hansen’s Disease (HD) literature in Japan, in which she illustrates that rationale for writing about illness is dynamic and dependent on social, cultural, and technological landscapes. She asserts that once Promin was developed as a treatment and cure for leprosy in 1946,15 there was a shift from ‘leprosy literature’ in which narratives were a heavily censored phenomenon that grew out of hospital administrators urging patients to come to terms with their incurable illness and quarantine policies, to ‘HD literature’ in which narratives became a politically engaged literature insistent on the restoration of human rights.’16 The rise in writing about HD experiences in Japan during the twentieth century signals a change in focus from illness narratives as therapeutic literature to a form of activism.

As discussed by Tanaka, written illness narratives like those by leprosy/HD patients highlighted above can be considered a genre in their own right.17 Writing specifically about HIV/AIDS, literature specialist Ann Jurecic draws attention to the fact that writing as well as speaking about illness publically in general is a relatively new trend that was fostered by the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States.18 Written HIV/AIDS narratives in English exceed the quantity of writing about flu, tuberculosis, polio, cancer, and other illnesses combined, and these narratives have proliferated due to increased distances between patients and practitioners in the medical profession, improvements in modern health care and understanding of HIV etiology in which a treatment or cure appears feasible, women’s liberation, gay liberation, and the ‘inability of master narratives to give meaning to suffering in the modern era… [as well as] the technological advances that promote self-publication and the global distribution of information.’19 In other words, the socio-cultural, technological, and medical climate in the United States has allowed for illness narratives, particularly written HIV/AIDS illness narratives, to become very public there – just as leprosy/HD narratives did in Japan (although the timeframe is not the same). In addition, even though the HIV/AIDS narratives in Japan I discuss below have not attained the same status or recognition as the Japanese leprosy/HD literature described above, the distinction between ‘before treatment’ and ‘after treatment’ conditions for writing (i.e., preparing for disfigurement and a slow death as opposed to learning to live with the stigma of having been infected) fits both illnesses.

Similar to Jurecic’s assertion that the proliferation of public discussions of illness is a relatively new phenomenon in Anglophone media, direct discussion of illness appears relatively recent in Japan when considering the issue of disclosure in self-help groups versus patient disclosure and disclosure to friends, family, and coworkers. Paul Christensen’s work on Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) in Japan is particularly instructive here: he describes how members of AA in Japan disclose to the group but keep their status as alcoholics and AA members secret in daily life,20 indicating inability to fully ‘come out’ or speak publicly about alcoholism as a social problem for fear of stigmatization or harassment not just as individuals, but as family members or company workers. But ramifications are further complicated when the person in question is experiencing an infectious disease and the medical community is involved due to differences in who is disclosing to whom, and what the perceived risks are for the individual and for society. For example, as Susan Long has illustrated, medical practitioners may disclose a terminal cancer diagnosis to the family of a Japanese patient rather than the patient themselves as a form of kindness or mercy.21 The patient is usually able to ascertain the diagnosis indirectly; this type of disclosure preserves the humanity of the patient by allowing the family to focus on continuing with daily life rather than focusing on the person’s approaching death. But for people with illnesses that the general population may associate with ‘deviant’ or ‘abnormal’ behavior, disclosure by patients to others is more about avoiding stigma and discrimination whereas disclosure by medical practitioners to patients’ families is about avoiding psychological trauma to the patient. In fact, early in the epidemic, the medical community feared disclosing an HIV diagnosis to patients who had been exposed to HIV through medical treatment and indeed failed to disclose to them, while publically disclosing the HIV status of sex workers.22 Once this was discovered, it became a patient rights issue; the infectious nature of HIV essentially forced the Japanese medical community to re-think the family model of disclosure because of risks to public health and family relations if HIV/AIDS patients were not informed of their HIV status but family members were.23 In short, the emergence of HIV/AIDS issues made illness a topic of conversation (as it did in written form in the U.S.), but the context in which this happened was rife with stigma and discrimination against those perceived to be polluting the body politic – problems that, as presented below, yōseisha still experience.

With regard to spoken illness narratives in particular, these may have roots in self-help groups such as AA in the United States in the 1930s.24 Rooted in Protestantism, AA incorporates characteristics of religious witnessing, including public (or semi-public) statements about personal experiences, confirmation of faith in the group and invitations to others to join, confirmation of solidarity of the group, a learned, patterned form of experience narrative, and re-writing of personal history according to experience with the group.25 These characteristics, having been secularized to some degree, are also apparent in non-religious self-help groups; as indicated above, AA itself is also active in Japan and its presence may have influenced the proliferation of self-help groups. In fact, the tendency for yōseisha to speak about their status in peer support groups may look similar to disclosure in AA meetings in that yōseisha tend to give a brief introduction and are encouraged to talk about what is bothering them. However, unlike alcoholism, HIV status is often tied up with other tabooed topics such as homosexuality. For example, one of my interviewees, a Japanese civil servant from Kansai, stated, ‘it’s harder for me to tell my parents that I’m gay than I’m HIV positive.’26 He continued to say that he had not told his parents about his HIV status because he would have to tell them how he got it (through sex) – and that he is gay. Interestingly, these are things he is willing to disclose anonymously in public. It is precisely these differences – the association with supposed ‘abnormal’ sexuality and the willingness to speak out (albeit anonymously) about it – that make HIV narratives different from other illness narratives in Japan. The pressure that some yōseisha feel from other members of society that somehow they are ‘not normal,’ often doubly stigmatized due to their illness and perceived means of transmission, has inspired them to write and speak about the realities of living with HIV in the hopes that they can increase public understanding and thus decrease stigmatization. They narrate their experiences with HIV in public ways not just to give order to their own experiences, but to encourage discussion of the feared and tabooed topics of HIV/AIDS and sex – things that are omnipresent due to various mass media representations and entertainment industries, but are considered ‘inappropriate’ for polite conversation or education.27

In addition to the variety of written and spoken illness narratives produced for various reasons and audiences, illness narratives may also be performed in various settings.28 Some of the most studied versions of such performances are clinical encounters, where patients and medical practitioners play particular roles (or refuse to play particular roles); otherwise, there is little literature that describes the significance or the embodied, performed illness narrative – particularly in conjunction with written and spoken illness narratives. Moreover, it appears that attention to these topics provides us the chance to see the emergence of new forms of Japanese narrative as well as the opportunity to see how some Japanese not only combat tabooed topics, but also reject the premise of similarity inherent in the often-heard phrase, ‘we Japanese’ (ware ware nihonjin 我々日本人).

Flexible kata

Kata (方) is a form or a way of doing something such as the stroke order of writing a Chinese character, the placement of flowers in a flower arrangement, the motions in tea ceremony, or even moves in martial arts. Although often used in reference to fine arts and martial arts, it can be applied to everyday or professional tasks as well, such as making a dish, filling in forms, or even talking on the telephone. In the analysis of narratives below, I discuss how the way of telling about life with HIV/AIDS, or kata, is on one hand fairly consistent in terms of the components they include regardless of the mode of presentation, but adapted to the needs of individuals, audiences, and events on the other. In this way, the kata of HIV/AIDS narratives in Japan is quite flexible when compared to the kata of tea ceremony, calligraphy, and flower arrangement. Drawing from Yano’s assertion that one must have mastered kata in order to break kata – and thus push forward a form of art – I consider the narrators of HIV/AIDS as masters: having perfected their own versions of HIV/AIDS narrative, they (not the general public, mass media, or medical profession) are the masters of explaining what it is to live with HIV/AIDS.29

Methods

The narratives discussed here were gathered by the author between 2010-2012 during ethnographic research conducted with NGO/NPOs that support yōseisha in Kyoto and Tokyo. The author translated several excerpts from the popular booklet, ‘Living Together: Our Stories’ which was published by Japan’s first and foremost HIV/AIDS community-based organization, Place Tokyo.30 The author conducted 75 semi-structured interviews (including yōseisha as well as HIV- Japanese)31 and conducted participant observation at several events including the AIDS Bunka Forum and PLANET Candle Parade described below. The data from the AIDS Bunka Forum Yokohama talk by Ms. Ishida and Dr. Iwamuro are derived from notes taken by the author (recordings were not permitted) as an audience participant in 2011. The data from the PLANET Candle Parade were collected through participant observation of the parade in which the author walked alongside and amidst other participants in 2011.

Talking the Talk: Written HIV/AIDS narratives in ‘Living Together: Our Stories’

Place Tokyo is Japan’s first, most established, and arguably most far-reaching HIV-related support organization. Place Tokyo has been working to provide support for yōseisha since 1994; the organization pre-dates UNAIDS by two years. Founder Ikegami Chizuko was inspired to start Place Tokyo after spending several years working with sexologist Milton Diamond from the University of Hawai’i and staff at the Life Foundation in Honolulu. The mission of the Life Foundation32 is “To stop the spread of HIV and AIDS. To empower those affected by HIV/AIDS and maximize their quality of life. To provide leadership and advocacy in responding to the AIDS epidemic. To apply the skills and lessons learned from the AIDS epidemic to other related areas of public health or concern.”33 The idea was to create an atmosphere that stymied stigma and discrimination while also providing social support, testing, and information on medical care and services. Thus, The Life Foundation created a comprehensive support system that included telephone help lines, a buddy system,34 AIDS education programs, and research.35 These foci are clearly visible at Place Tokyo, which offers telephone counseling and peer group meetings and events and also creates educational materials and conducts research. Place Tokyo also emphasizes the importance of fostering a positive environment with regard to HIV.

The importance of ‘living positively’ was also carried over from the Life Foundation to Place Tokyo: “Place” stands for Positive Living And Community Empowerment. “Positive Living” refers to “living as yourself;” “Community” refers to a group of people who collectively and actively engage in activities to create a healthy environment and foster interest and concern for others in daily life; “Empowerment” represents learning how to channel one’s inner power, whatever it is and in whatever way is best for an individual.36 Ms. Ikegami further notes that empowerment starts at an individual level, but is necessary on the societal level for social change. In this way, empowerment is considered multi-dimensional and interactive. Ms. Ikegami describes the timing and the start of the organization this way:

Place Tokyo has been functioning as a research network since 1995. The World AIDS Conference was held in Yokohama in 1994. At that time, NGOs and CBOs played a really effective role, so the administration for the first time recognized that NGOs and CBOs also provide valuable input in HIV policies. And then, they also realized that if those groups want to do research, it should be considered. Up until then, “HIV/AIDS research” was something that was only done by scientists and physicians. But there is research that really only CBOs are able to do.

The first real research that we did was an assessment based on HIV+ people’s input. For this research, of course we included someone who could act as an HIV representative and participate in the research team and checked everything from choosing the topics on. Until then, there had been no research like that. In particular, there was nothing but notifications from yōseisha through doctors who did this and that in their own offices. And we thought, “Is it OK to keep doing it like that? And how does how it’s done influence what kind of information is considered desirable? Maybe we should make sure the information given by the yōseisha benefits the yōseisha”… From getting the people who are affected involved, to focusing on prevention, and now care, that has been our trajectory.37

In addition to research and publication, other activities were simultaneously taking place to keep both yōseisha and the general public tuned in to HIV issues: peer support groups, newsletters, and telephone hotlines provided spaces for dialog about living with HIV. Research informed how these activities were executed, and activities shaped research. In other words, the relationship between outreach and research is dialectical in nature. Essentially, Place Tokyo has grown from a group of people that collected and digested information for the public and for yōseisha prior to 1994 into an organization that conducts research alongside yōseisha that not only contributes to understandings of HIV/AIDS in Japan but facilitates education, counseling, and improvement in the quality of life for people in the community.

“Living together. If you can find yourself in the sentences of these pages, we’ll be grateful.”38 So begins Place Tokyo’s booklet, “Living Together, Our Stories,” which is about living with HIV/AIDS. Notice how the editors, from the first page, deftly encourage readers to “find themselves” as a way of “living together.” Self-reflection and self-care are means to understanding others and building a positive environment or society. I will not reproduce the lengthy discussion about individualism versus groupism that has permeated discussion of Japan by academics and is also present in everyday discourse there;39 but I do want to highlight the significance of this perspective. This philosophy of actively making a positive environment everyone can live in by understanding and caring for the self is a response to what Place Tokyo founder Ikegami Chizuko recognizes as an “environmental problem” in which Japanese, particularly young Japanese, have been passive participants in society who leave decisions – even decisions about safer sex – up to others.40 Focusing on how social problems and public health issues like HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are perceived by young people as “not their problem,” she asserts that this attitude perpetuates blame and stigmatization because the spread of infectious disease is something others should “not spread” rather than something they themselves should protect themselves from. One of Place Tokyo’s goals, then, is to change the environment (society) by encouraging frank discussions about sex and sexual health so that individual and public health is improved. It is important to point out that according to Place Tokyo, improving public health is not limited to decreasing the incidence and prevalence of STIs like HIV; rather, it includes building a supportive (positive) environment for everyone – but particularly for people who have experienced some form of discrimination. One way to do this is to foster communication – to break the taboos against speaking honestly and openly about sex. Ms. Ikegami describes their campaign to encourage couples to talk about sex and condoms this way:

Just getting information doesn’t connect to preventative behavior. What is obstructing preventative behavior with regard to sexually transmitted HIV in Japan? … In the case of female students, they hesitate with regard to their male partners, and find it difficult to strongly say for themselves that they want to use protection, or convince them to use it… In male students the same age… it’s that they’re not used to using them. They think they’re uncool or don’t feel good or destroy the mood. [So we want to tell them], if you’re not used to it, you should get used to it, right? About the relationship factors in the females, girls think that if they strongly assert themselves, it’s not ladylike or it leaves a bad impression, but we want to tell them, you’ve got the wrong impression. Boys don’t actually think that. But if the partners communicate beforehand, these misconceptions clear up, and they should think about that. If we change the image to make it positive, that preventative behaviors are cool, whether you’re male or female you can protect your sexual health – we want to spread that message widely. “It’s YOUR problem.” They think it’s not their problem but someone else’s. But it is their problem. It’s “our” problem, is what we want to say...41

“Living Together: Our Stories” is an example of how Place Tokyo combines research, education, counseling, and outreach in a single publication. Through this first poem, readers are drawn into experiences of living with HIV/AIDS – for those infected, for their friends and family members, for their partners (many of whom do not have HIV). Through the assertion that someone “faces it… is told they have it… decides to live with it” everyday, and the invitation to find themselves in the booklet, readers are also encouraged to think of themselves as that “someone,” to see HIV as an issue they can own through becoming more knowledgeable and taking charge of their own sexual health. To facilitate this, the stories are interspersed with columns by Ikegami and Ikushima Yuzuru, a medical social worker who counsels people living with HIV/AIDS at Place Tokyo. Readers also find the Place Tokyo website at the end of the booklet, and are encouraged to visit it so that they can find out more about the organization, its research and resources, and HIV/AIDS in general.

Through the inclusion of narratives from various types of narrators, this booklet serves as a resource for readers who may be drawn in by the drive to “find out” about the lives of “real people” living with HIV; readers who may be searching for the words of someone else to comfort them, to feel that they are not alone in their diagnosis; readers who may be searching for information about how to interact with a loved one living with HIV; or readers who simply want to know more about HIV and where to get “good” information. Here, I focus on the narratives by yōseisha because these written narratives provide us with some insight about the typical structure of HIV/AIDS narratives in Japan.

“At First, I Just Thought of Suicide” By KN42

Even now sometimes when I think back on when I found out, my chest hurts. I never felt so panicked and full of despair. I just felt death was so real. Of course, I had some knowledge of what HIV/AIDS was, but at the moment when I found out, it just evaporated.

At first, I thought of nothing but suicide. I’m going to die anyway, so it might as well be now… there’s not going to be a cure in my lifetime… But the people around me wouldn’t accept that, and the days went by.

Before I found out, I didn’t like myself at all and I was really careless. I wasn’t good at my job or being with others, and I had lost all confidence. And then I started feeling really bad, and I wondered, “I can’t really have THAT…” but I went and got a test.

Actually, I’d had a test two years before. Then I was negative, and the way I was treated at the test center was very business-like. But the day I found out, I was treated totally differently. I was taken to a room with no window, and I could hear other people being told they were negative through the door. “Why am I being made to wait here this time?” “Maybe…” “No, it can’t be…” As I thought, my throat got dry and my hands were wet with sweat. After a short while, I was taken into another room again and I was told the result. I started to panic and broke down and cried.

This time, the results of the blood test showed I needed to start taking medication right away, but that I wasn’t showing symptoms of AIDS. The doctor said, “That’s really lucky!” But at the time, I couldn’t understand that.

For me, the courage to live with HIV came when the attending physician said, “I can help you.” Before that, I hoped for “a death” from everyone around me.

Living with HIV, I’ve rebuilt my self confidence and started over. In the last 2 years plus, I’ve thought, “I can’t do it anymore!” many times. But recently, something about me is different… I’ve been able to like the self that chose to live with HIV a bit more than before. So now when I think “I can’t do it!” or when I’m faced with something over and over, I’ve become able to think, “I can definitely get through this.” So, I like myself, the me that thinks like that, better.

I don’t know how many years I’ll live. I don’t know what ordeals are waiting for me. I’ve only rebuilt myself part-way. But maybe that is “living.”

That’s what I think now. “HIV is a big chance to re-think my life, myself.”

So, “no matter how hard it is, I can overcome it.”’43

KN begins the narrative with the panic and despair that accompanies disclosure. For this yōseisha, such feelings were so intense that suicide seemed like the only way out since they were “going to die anyway.” In fact, HIV negative members of the Japanese general public I interviewed nearly always linked an HIV diagnosis to death: “When you get eizu, you die,” a middle-aged Japanese salaryman told me.44 Perhaps this is because HIV and AIDS are elided in the Japanese term eizu (as noted above) and also because HIV is only visible to the naked eye when it progresses to the point that people experience lesions and wasting, the hallmarks of AIDS and signs that suggest imminent death. These links with death, paired with the tendency for HIV in Japan to be transmitted primarily through sex,45 have made it a taboo topic that people find it difficult to discuss openly in serious contexts.

Next, KN goes back in time, describing their lack of self worth and the lead up to the test. This provides a point of comparison for the self evaluation at the time of writing (discussed below), and admission that the positive test followed a negative test a few years before allows them to compare what it is like to be given both negative and positive results. Noting that they could hear people being told they were negative and the sense that this time was different, KN describes breaking into a sweat and finally breaking down in tears upon hearing the HIV test was positive this time. Because of the trauma of diagnosis, they were unable to comprehend the doctor’s assessment that although they needed medication, they had not progressed to AIDS. Many yōseisha, both in writing and in interviews with me, stated that because they associated HIV with death and because they considered it “someone else’s problem” prior to diagnosis, they were filled with self-blame upon diagnosis and that such ideas were barriers they had to overcome in being able to accept their HIV status. Another writer, K, put it this way:

When I was told I was positive, my heart was filled with fear and humiliation… When directly faced with various hard facts at the hospital, I felt… as though I was guilty of a terrible sin. The image of this illness that has been presented up until now is that it’s something not worthy of consideration or encouragement. Even I, myself, someone with HIV, had this strong, discriminatory view.46

Returning to KN’s narrative, they move on to describing the decision to live with HIV, stating that that became possible when the doctor made it clear that treatment and care could improve their condition. Finding support was the turning point. From there, KN describes taking charge of their life, and realizing that “I like myself… better” now than they did before the HIV diagnosis. This was also a common theme in my interviews with yōseisha. For example, a retired accountant in his 60s who had been living with HIV for 25 years stated, “HIV is only part of me” when discussing his acceptance of HIV.47 These messages, when made available to others, serve as reassurances to newly the diagnosed that they are not alone and that they can live a good life with HIV. In other words, the writings of yōseisha make them part of a peer network even if they never meet their readers face to face, and such writings aim to tell readers that HIV is not a death sentence.

To summarize, the framework, or kata, for the written yōseisha narratives in Place Tokyo’s booklet includes 1) pre-diagnosis and the diagnosis, 2) difficulty with acceptance and disclosure, 3) finding support, 4) becoming part of the peer support network, and 5) final comments about life with HIV. This is the general trajectory in the 2005 booklet as well as the narratives included, but the order and emphasis of these components is flexible and varies from writer to writer. The overall style of writing is colloquial and confessional, highlighting each writer’s voice and feelings, thereby lending authenticity to each story while also giving readers the sense that the writers are speaking to them. Moreover, the disclosure of intimate feelings and experiences allows readers to feel that they know someone like KN or K or they are like them somehow, even though the identities of the writers have been protected. In fact, it is even difficult to ascertain the gender of most (but not all) writers. Essentially, the style and framework allow the writers to reach out to others and not only share their stories, but create an opportunity for Japanese to talk about HIV/AIDS as a domestic problem – to break the taboos surrounding it. Use of this flexible kata, which allows for a delicate balance of intimate sharing while protecting one’s identity, is also discernable at the HIV/AIDS events described below in which yōseisha speak publicly about life with HIV/AIDS. Considering the steady support Place Tokyo has provided for yōseisha since 1994, perhaps this is not coincidence.

Talking the Talk: Performing HIV/AIDS Narratives at the AIDS Bunka Forum in Yokohama 2011

AIDS Bunka Forums are two-day, conference-style public events held annually across Japan. Anyone can attend and admission is free. They are widely publicized and students in particular are encouraged to come. Activities include workshops, guest speakers, concerts, red ribbon manicures, and art exhibits; NGOs/NPOs generally have booths set up in common areas. The longest running Forum is the AIDS Bunka Forum in Yokohama. Participants include people interested in learning about sexually transmitted infections, sexuality and gender spectrums, and groups that support sexual minorities. The list of guest speakers usually includes those who agree to speak about their experiences with HIV in such public venues. Such yōseisha are, importantly, different from most yōseisha in that they are comfortable in their diagnosis, willing to talk about it with others, and also able to speak with large groups. Unlike the truly anonymous yōseisha who writes about their experiences, there is the added risk for guest speakers that they may be recognized if an acquaintance opts to attend. It is a risk they accept. But other risks, such as being asked questions they are not willing or ready to answer, for example, are carefully managed by the structure of the narrative and the settings, which include the presence of a supporter. Similar to written narratives, a key strategy is to give the audience just enough details about a yōseisha’s personal life so that they see the human face of HIV, but not enough to open the speaker up to stigmatization and discrimination. Another way to put this is that the kata of the HIV/AIDS narrative is expanded to include the physical presentation of self as a method to help the audience learn about HIV/AIDS by challenging its status as a tabooed topic.

At the 2011 AIDS Bunka Forum in Yokohama, Ms. Ishida took the stage and Dr. Iwamuro introduced her, giving the audience time to take in both participants visually. Ms. Ishida’s hair was stylishly bobbed. She looked vibrant and beautiful in her flowing blue tunic, black leggings, and sandals: there was nothing to separate her from any other Japanese women in the audience in terms of her fashionable appearance. Her doctor, Dr. Iwamuro, is well-known for his role in founding the forum and appeared to be a typical middle-aged professional with glasses and graying hair. The only thing that made him stand out was his famous condom-print tie; but this probably went unnoticed by many in the audience.

The two began a conversation about her life and experiences with HIV, noting that she could not speak for all yōseisha.48 Dr. Iwamuro asked Ms. Ishida about how she found out that she was HIV+, the circumstances surrounding her infection, the symptoms she experienced, the difficulties of disclosure, the care she was offered, and her daily life. Through this interaction, the audience learned things about Ms. Ishida that Dr. Iwamuro already knew. She is married and has a child. All pregnant women in Japan are tested for HIV, and that is how she found out she is living with HIV. She got a tattoo several years ago and experienced flu-like symptoms (fever, swollen glands) afterwards but thought she had just gotten a bug that was going around. She was shocked to find out she was HIV+ during a prenatal exam, commenting that the tattoo parlor49 had probably re-used their needles. She told the audience that she had a lot of difficulty telling her family, but her doctor helped her by being there when she told her mother. She couldn’t bring herself to tell her father; her mother told him for her.50 At the clinic she visits, the staff all know her and are very friendly to her – she said they notice whether or not she has gained or lost weight and whether she appears happy or not. Before opening the session up for questions, she noted she is living an everyday life taking care of her child, but that it is sometimes hard because there is still a lot of discrimination.

Together, Ms. Ishida and Dr. Iwamuro constructed a narrative that guided the audience through her experiences with HIV/AIDS. Importantly her kata, though spoken on a stage and performed in collaboration with an interlocutor, is similar to the written narratives described above. Like KN, Ms. Ishida describes her diagnosis, various traumas she experienced related to this diagnosis (such as inability to tell her father her HIV status), and finding support from the medical community. During the question and answer session that followed, Ms. Ishida described her decision to live with HIV and taking responsibility for the choices she made that lead to her infection: as she answered questions about her feelings – such as whether or not she regretted getting her tattoo – her doctor answered medical questions. Dr. Iwamuro also exhibited great skill in unobtrusively steering the audience away from questions that may have been too personal for Ms. Ishida, such as those about her family life or sex life. Rather than answer questions about her sex life and the birth of her child, for example, Dr. Iwamuro discussed safer sex and ways to prevent transmission between serodiscordant couples and from mother to child. To use Goffman’s theory of presenting the self, they crafted a careful impression that would not embarrass Ms. Ishida or others in front of the audience;51 however, their collaboration was more protective than Goffman’s theory intends because the goal the organizers had was not for the audience to get to know Ms. Ishida or Dr. Iwamuro. The goal was to get them to know HIV through Ms. Ishida’s and Dr. Iwamuro’s narrative. While the audience learned about what it is like to be tested, to disclose to family members, and to get treatment through her narrative, most of Ms. Ishida’s personal identifiers were carefully and purposefully omitted.

Thus, Ms. Ishida’s narrative gave the audience a specific image of someone living with HIV: a beautiful, articulate young woman with a son, someone not much different from the audience members, perhaps. This encouraged the audience members to see that HIV can infect and affect anyone in Japan, and contrasts sharply with mass media portrayals of HIV+ Japanese women (who are a small minority of Japanese cases in the first place) as selfish and dangerous.52 Rather, this educational narrative crafted by two seemingly “normal shakaijin(社会人)”53 provided the audience a chance to learn about safer sex, mother-to-child transmission, and personal responsibility for self preservation. For example, when asked about whether she was angry with the tattoo parlor, Ms. Ishida was adamant that she had chosen to go there in order to pay less than she would have if she had gone to a “regular” shop. Although she said she sometimes regretted all the trouble she had experienced for such a trivial thing, she claimed responsibility – and asserted that the audience members needed to do the same thing when making choices. In this way, in addition to providing a “yōseisha face and experience” that they want to see or “consume,” and providing an introduction to living with HIV, Ms. Ishida was able to use her narrative and questions from the audience to challenge the audience to think about their choices and take responsibility for the consequences. This challenge echoes Ms. Ikegami’s goals of encouraging young Japanese to take charge of and be responsible for their own sexual health. It also creates not just an opportunity (as is the case for the written narratives) but also a space for those living with HIV/AIDS to assert their normalcy as Japanese and to contradict the oft-heard claim that HIV is a “foreign” problem, or a problem of “deviants.” In addition, her healthy appearance literally shows audience members that HIV does not equate to death.

There are a few points to summarize regarding public, oral disclosures like these.54 First, speakers such as Ms. Ishida are not alone when they speak: peers or support staff join the speakers on stage, and form part of the audience. This arrangement provides emotional support and allows for the redirection of questions that speakers may not be ready or willing to answer. Second, speakers use pseudonyms or professional names that they themselves have selected. This gives them the power to select the personal information they are willing to share in that specific setting. A speaker at another event asserted that HIV is only five percent of his life, of himself. Amongst his friends, of course he uses his given name; some people in his everyday life know he is a yōseisha, but his HIV status is not the defining element of his identity to him or the people closest to him. However, when he speaks publically as a yōseisha, he is Mr. Y: he highlights that five percent because that is what is asked of him, and he reminds the audience that they are only seeing part of him. For yōseisha, it is safer – both in terms of an individual’s mental health and in terms of avoiding discrimination – to highlight these experiences rather than personal details when speaking to the general public about being HIV+. Third, although there is an element of performance involved in the telling of such narratives (discussed below), this does not extend to making changes in appearance – either to embellish or hide certain individual attributes. Their narratives cast them as yōseisha, and their clothing and comportment cast them as members of the general public. This is important because many people who have no personal experience with yōseisha tend to imagine them as outside the general public and as belonging to special groups. Therefore, one of the take-home reminders of these sessions is that yōseisha are members of the general public. Fourth, the narratives are physically regulated by several means: by the placement of the sessions at the end of the day so people are unlikely to linger afterwards; holding sessions in large rooms so people are more likely to self-monitor their questions; structuring the session to fit a specific time frame with a clear end time; contextualization of the session within a larger event; planning for the speaker to enter after the audience is convened and leaving before the audience departs (if the speaker so desires); and including key supporters (such as friends or physicians) in the audience.

These interactions make it clear it is not just Ms. Ishida and Dr. Iwamuro who shape the narrative: by the end of the session, it was obvious that the audience and the organizers had roles in shaping it, too. To use Kleinman’s terminology, Ms. Ishida, Dr. Iwamuro and the audience all worked together to develop an “explanatory model” of HIV that they could all understand and use to share information55 – all without making any specific references to Ms. Ishida’s personal life or allowing the audience to approach her alone prior to or following her session. This is yet another example of flexible kata: while components of the narrative are relatively constant, strategic disclosure, the steering of audience members’ questions, the control of the room and of Ms. Ishida’s entrance and exit, all work to protect her as she describes living with HIV. Another way to think of this is to say that the flexible kata set on paper with the Place Tokyo booklet in 2005 is now being adapted for stage. In fact, as I describe below, the use of flexible kata is also discernible at HIV/AIDS events where the role of speaker/participant has less emphasis on audience education and more emphasis on memorialization and activism.

Walking the HIV/AIDS Narrative: The PLANET56 Candle Parade 2011

“There are many people in Japan living with HIV. I am one of them. Stigma and discrimination are not going away. We cannot forget that eizu is a social disease...” began Hunky, a Kyoto resident who lives with HIV. Moments before, he had walked up the stone steps of City Hall at dusk, and taken the microphone from Ms. Odagiri, one of the event organizers. As he talked about continuing to fight against prejudice and stigma, his voice wavered just enough for me to notice. But his message about the importance of talking openly about HIV was as clear as the thick, white letters inked on his blue t-shirt that read, “I am HIV positive.”

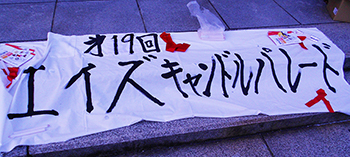

When he finished, it was almost dark. Parade participants organized into a line behind a large, white banner that featured a red ribbon and the name of the event written in large, black letters. Hunky took one corner and gestured for me to take a section next to him. We all walked from City Hall to Gion, and the procession was a relatively quiet one (particularly compared to the protest against nuclear energy that walked the opposite route that night). People talked in low voices with loved ones or walked alone – all carrying flickering candles in paper cups that sometimes dribbled hot wax down their hands. Someone played a flute as we walked, and Ms. Odagiri’s voice rang out over the loudspeaker: “We are from PLANET, an organization that remembers people lost to eizu and promotes awareness of HIV. Won’t you walk with us?”57 This was punctuated by stops in front of shops displaying red ribbons on their facades; in the days before, several of us had visited the shop owners along the parade route and asked if they would put up a red ribbon in their window to show their support.58 Every time we passed such a shop, Ms. Odagiri would thank them over the loudspeaker and there was an exchange of bows – often through the shop’s windows. When we reached the park, people were invited to give their impressions of the walk. No one spoke as a yōseisha, but several people remarked about the power of being part of the walk itself.

Unlike Ms. Ishida’s narrative above, Hunky did not talk about the circumstances of his infection or his everyday life. He did not tell the audience about his progression from diagnosis to acceptance, or tell them they had to be responsible for their actions. He did not have to do any of these things because the participants – despite being open to the general public – was a much more specific one than the crowd at the Bunka Forum. Although anyone can attend PLANET’s candle parades, participants tend to be those who have personal experience with HIV/AIDS, either as yōseisha, through loss of a loved one, or through professional experience (i.e. medical practitioners or educators). Speaking to a sympathetic, even empathetic, audience who had their own experiences with HIV, Hunky focused on the importance of talking about HIV openly as a tool to fight discrimination rather than talking about his experiences as a yōseisha.

Although Hunky’s speech does not fit the kata we see in the written narratives of KN and K or in Ms. Ishida’s spoken narrative at the Bunka forum, his actions at the parade do. From the beginning of the event, Hunky announced his HIV status, both verbally and through his clothing. During the parade, he carried the banner; but he also passed it off to others and mingled with the crowd. Walking with other yōseisha and people who have lost loved ones to HIV/AIDS expresses solidarity of shared diagnosis,59 shared experiences of living with HIV/AIDS, and shared support. At the end of the walk, Hunky joined the rest of us in the park – dark but for our candles – and listened to people give their impressions of the walk. He joined the organizers for dinner, popping his ARVs in his mouth, and washing them down with beer and battered fish between bits of conversation. Hunky’s participation – speaking, walking, sharing opinions and food – simultaneously signaled his acceptance of his HIV status, his role as a peer and public activist, and his comfort with himself as someone who lives positively with HIV.

Mattingly has argued that “narratives may be acted rather than told,” stating that such “living narratives” suggest the possibility of healing.60 Further, she notes that such performed narratives are similar to healing rituals in that 1) heightened attention to the moment gives the event legitimacy, 2) a number of sensory cues express/create meaning, 3) aesthetic, sensuous and extralinguistic interactions are highlighted, 4) the experience is socially shared, 5) the people involved reflect on the past, present and future, situating themselves in a particular history, as a method of healing, and 6) participants can be transformed.61 Each of these criteria is met by the event: all participants exhibited a heightened attention to HIV/AIDS, whether individual focus was on personal loss or grief, efforts to raise social consciousness, or a combination of the two. Some people dressed up in kimonos, some dressed “smart” as though out on a date, and many wore red ribbons. Everyone carried candles. People walked together, grouped together, listened to the flute and Ms. Odagiri’s voice as we moved steadily up the street and towards Gion. This was the nineteenth annual parade, and posters showed pictures of some of the first marchers who were now deceased.

There are three key differences between the Bunka Forums and Parade that demonstrate yet more flexibility with the HIV/AIDS narrative kata. First, participants at the Bunka Forums are all voluntary participants – people who chose to learn about some aspect of HIV/AIDS and/or gender and sexuality – whereas the members of the general public present at the Parade were crowds of people shopping in Gion. This meant that the latter were not nearly as engaged as the audience members at the former; yet, this parade made HIV/AIDS visible to members of society unlikely to attend events like the Bunka Forums and unlikely to consider HIV/AIDS their problem. And although some carried photographs of those lost to HIV/AIDS, yōseisha like Hunky were part of the parade and demonstrated their vitality. Thus, the Candle Parade is an important avenue not just for memorializing the dead and supporting yōseisha (as opposed to education, the purpose of the Forums), but also for HIV/AIDS activism.

Second, the ways in which participants created the narrative at the parade was different. Although the audience members were drawn into the narratives at the Bunka Forums through the question and answer sessions, they were relatively passive participants during the narrative construction between those onstage at the beginning of each session. In comparison, parade participants who walked the route were active participants throughout the event. For example, as noted above, Hunky walked, talked, ate, and drank his way through the parade and the events afterwards. Because he was asked to speak and helped organize the event, his actions stood out. But in reality, all the participants walked their narratives – some without saying a word. It is possible that the power that people said they felt during the procession was this sense of walking narratives together, in an atmosphere where the goals and the rules were shared by everyone. Moreover, this event provided an opportunity to examine how illness narratives can be embodied and performed. The people who saw the parade from the sidewalks cannot really be described as “participants” because few of them made any effort to engage with parade participants: some accepted education packets and condoms from student participants, but many either took quiet notice or seemed to ignore the parade completely.

Third, although the parade moving through Gion seems open and porous compared to Bunka Forum sessions in closed rooms, there were still several factors that functioned to control the setting. Those with shared experiences – membership in the same peer support group, those who suffered the loss of a common friend or loss of a child, for example – tended to walk together. Moreover, the pace of the walk, the darkness, the holding of candles, and the solemn mood discouraged interactions between strangers – with the exception of students who had been recruited to hand out condoms as the parade moved down the street. In Hunky’s case, this meant that although his shirt constantly announced his status as a yōseisha, he could vacillate from his “public yōseisha” role as a speaker and banner-carrier to other versions of himself as he moved around and talked to friends and acquaintances. In this way, not just Hunky’s privacy, but that of the other participants as well, was protected by the structure of the event – the darkness, the candles, the pace, the intimate groups. When people take part in this very public event, they are still able to maintain a sense of quiet privacy, all the while being supported by the presence of fellow participants. These three points highlight how the kata of telling (or walking) HIV/AIDS narratives is, again, flexibly used by participants to assert the importance of HIV/AIDS as a domestic issue of everyday Japanese and to challenge its tabooed status.

Conclusions

Producing HIV/AIDS narratives in Japan, like leprosy/HD narratives before them, is a means for yōseisha to order their experiences, educate the general public, and engage in activism. Written, oral, and performed HIV/AIDS narratives produced for public consumption conform to a “flexible kata” that serves to introduce the general public to issues of testing, diagnosis, disclosure, and acceptance in a way that suits the narrator’s storytelling style and the mode of delivery, all the while protecting the narrator through controlled disclosure of private information. This is relatively easy on paper, where writers can choose pseudonyms or initials and can easily omit personal identifiers since they do not come face to face with the audience. When speaking in public, the narrative kata is expanded to include an additional set of organizer controls. Limits of the narrative are set as organizers control the speaking time (length of narrative, and position in the program), the entrance and exit of the speaker (orchestrated to avoid the speaker being cornered by someone from the audience), contextualization of the narrative (such as at a Bunka Forum, where the audience expects to hear about the topic), and embedding speaker support either by providing a moderator (such as Dr. Iwamuro) or by including friends in the audience. Speakers also prepare what will and will not be disclosed. Much like the written narratives, these “performed” narratives are carefully crafted so that audiences can learn about HIV through the speakers, but the audience actually learns very little about the personal lives of the speakers. In addition, narrators hope that their physical presence defies the stereotype that HIV=death, and that the audience becomes able to see yōseisha as everyday Japanese as they learn about HIV/AIDS. In the case that speakers seem to be different from audience members, speakers rely on their ability to convey their humanity, what it felt like to find out one’s HIV status for example, to push for acceptance and acknowledgement of a diverse population in Japan. Diversity even amongst yōseisha is stressed by the common assertion that “I cannot speak for all yōseisha” that I heard at each one of the public talks and was repeated in private interviews. This is very different from the common phrase, “we Japanese” that often crops up in conversation. This subtle, but very purposeful attempt at activism is just one example of how the educational atmosphere at events like Bunka Forums is blended with activism.

In instances in which yōseisha actions can be understood as embodiment of the HIV narrative form, such as participation in an AIDS walk, the activist elements are clear. Hunky’s assertion that “Eizu is a social disease” was made through a loudspeaker from the steps of City Hall. He wore a shirt that asserted his HIV status, and carried an HIV/AIDS memorial banner down the main street of Kyoto along the same path that people protesting nuclear power took. Unlike the Bunka Forums where people chose to set aside time and learn about various issues related to sexual health, the goal for the “audience” at the AIDS walk – the people walking down the street – was to increase visibility and bring the issue to people who perhaps rarely, if ever, thought about HIV. It was a method to bring HIV/AIDS, if not to people’s doorsteps, then literally to Main Street (Gion). It was a strategy not unlike Ms. Ikegami’s, to encourage local people to think about HIV as “your problem… our problem.”

Although all three types of narratives above utilize what I have termed “flexible kata,” the spoken and embodied narratives by Ms. Ishida and Hunky differ from the written narratives regarding what I have referred to as a performative element. The significance of this element cannot be ignored because it is what sets them aside from the many, many people living with HIV in Japan. To put it plainly, Ms. Ishida and Hunky are not typical yōseisha. They represent just a small percentage of yōseisha who have the ability to stand in front of an audience and talk about their lives as HIV+ people. They have known about and been accepting of their status for several years. They received guidance and support (but no formal training) in public speaking. They are active in organizations that support people living with HIV/AIDS. They participate in spreading information about HIV by speaking in public, running peer group meetings, participating in HIV/AIDS events, and helping to prepare education materials. Thus, they are different from the vast majority of yōseisha who do not do these things. In fact, one yōseisha pointedly mentioned at an event that, “Not everyone can do peer support.”62 To elaborate, not everyone living with HIV is physically, mentally, socially, or financially able to make HIV activism a part of their lives.

Second, the desire to be active in HIV movements does not equate to being a “performer.” There are countless people who work in research, prevention, and counseling who never take center stage. Rather, these speakers’ personalities, experiences, access to resources, and imbedded-ness in social networks combine in such a way that they are able to tell their stories as “public yōseisha.” Quite simply, they are good at being on stage; they might not have started out this way, but they had the drive and the support necessary to do what they do.

Third, there is an element of preparation that is essential to public speaking. As discussed above in detail, there is a specific time, place, and target audience for each narrative. Neither Hunky nor Ms. Ishida read from a prepared script or had memorized what to say. But they did think about what they were going to say (and not say) before they came. The settings of the events required it, although it is easier to see in some cases than others. In Ms. Ishida’s case, for example, it was evident that the two speakers had agreed upon what would be asked and how they would respond to audience questions beforehand. Again, these public narratives about living with HIV are planned and carried out by people with all the resources they need to do so. These performances were not something that someone did spontaneously, without prior thought, in a public place like a park or the train station. They were performed at specific venues, with the assistance of specific agents, and with specific goals.

Although these characteristics sound similar to theatric performance and that “performance” is often associated with actors, characters, and works of fiction, I want to be clear that in discussing Ms. Ishida and Hunky as performers, I am not referring to them as actors. They do not perform shows or portray characters. The performances they give are not fiction. What they do when they are onstage is highlight the presence of HIV in their lives for the benefit of the audience – and to some degree, for themselves and their fellow yōseisha. To reiterate one yōseisha’s comment, “HIV is only part of me.” Thus, rather than actors on the stage who follow a script written by someone else, who portray a character by allowing that character to blend and bleed into themselves, public yōseisha formulate their own scripts and perform specific parts of themselves. Given this distinction and my use of kata, it seems more appropriate to say that the narrators described here are masters of HIV/AIDS narrative. Further, these masters have not only rejected erroneous assumptions of what it means to have HIV that perpetuated by the mass media, the general public, and even the medical profession, but have also rejected the assumption of Japanese sameness through their narratives. Thus, the narratives included here are examples of how yōseisha have been working to challenge existing taboos about sex and HIV/AIDS, and even what it means to be Japanese. In Ms. Ikegami’s terms, they are trying to change the environment by encouraging the audience to re-think their impressions of HIV/AIDS and sex, and see HIV and other STIs as something that they can take the responsibility to prevent. To put it another way, the masters described here have redefined the talk and the walk of living with HIV in Japan.

NOTES

1 Ikegami Chizuko and Ikushima Yuzuru, eds., Living Together: Our Stories (Tokyo: Place Tokyo, 2005). This was originally published in 2005, so 20 years was accurate at the time it was written. The title of the booklet is in English although the contents are in Japanese. There are six stories of living with HIV and 5 sections on sexual health. The booklet concludes with a summary message and resources.

2 See Ikegami and Ikushima, Living Together. Translation by the author.

3 Modes of HIV transmission include intimate exposure to HIV-infected blood or blood products (such as Factor 8 which is used to treat hemophiliacs); vaginal, seminal, or rectal secretions; and breastmilk. Behaviors that facilitate infection include oral, anal, and vaginal sex without a barrier (such as a condom or dental dam); intravenous drug or vitamin use with communal, unsterilized needles; blood or organ transfer using unsterilized equipment or infected blood or organs. Mother-to-child (MTC) transmission can occur in utero, during birth, or through breastfeeding.

4 厚生労働省の平27(2015)年エイズ発生動向一文新結果一 (Kouseiroudousho no hei 27 [2015] nen eizu hassei koudou ichibun shin kekka) available at http://api-net.jfap.or.jp/status/2015/15nenpo/bunseki.pdf, accessed September 23, 2016.

5 The cause of about 9% of 2015 cases are listed as “unknown,” and another 2% are listed as “other” (厚生労働省 2015). Although intravenous drug accounts for a large percentage of HIV transmission in the US, there were only 2 cases in Japan in 2015; moreover, Japanese women have high testing rates and low infection rates that led to exactly one case of mother-to-child transmission rates that year (ibid).

6 Much like in the United States, a large percentage of hemophiliacs in Japan contracted HIV through use of HIV-infected blood products – products that were imported from the U.S. See Seki et al 2002 and 2009 for details.

7 It’s possible to further prevent MTC by prescribing ARV treatment to HIV+ pregnant and post-partum women, followed by anti-retroviral (ARV) prophylaxis for infants born to HIV+ mothers. There is also a pre-exposure prophylactic (PrEP) ARV that can be prescribed for high-risk populations.

8 See Runestad 2010, Miller 2002, Cullinane 2007, Allison 1994.

9 Personal communication, July 2011.

10 厚生労働省 (Kouseiroudousho) 2015.

11 See Elinor Ochs and Lisa L. Capps, “Narrating the Self,” Annual Review of Anthropology 25 (1996): 20.

12 Ibid. W.H.R. Rivers,Medicine, Magic, and Religion: The Fitz Patrick Lectures Delivered before the Royal College of Physicians of London in 1915 and 1916(London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd., 1924).

13 Cheryl Mattingly and Linda Garro, Narrative and the Cultural Constructions of Illness and Healing (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000).

14 See Kathryn Tanaka, “Through the Hospital Gates: Hansen’s Disease and Modern Japanese Literature” (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 2012). Leprosy is now called Hansen’s Disease (HD) and is named for the man who discovered the bacteria that causes it. Promin was the first antibiotic treatment to successfully treat HD; efficacy was demonstrated in the United States in 1941, but was not available in Japan until 1946.

15 Tanaka, 5.

16 Tanaka 2012 and Ann Jurecic, Illness as Narrative (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012).

17 Jurecic 2012.

18 Jurecic, 10.

19 Paul Christensen, “Struggles with Sobriety: Alcoholics Anonymous Membership in Japan,” Ethnology 49 (2010): 45-60.

20 Susan Orpett Long, Final Days: Japanese Culture and Choice at the End of Life (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005).

21 Melanie L. McCall, “Aids Quarantine Law in the International Community: Health and Safety Measures or Human Rights Violations?” Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Journal Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Journal 15(4): 1001–1028.

22 Y. Seki, Y. Yamazaki, Y. Inoue, C. Wakabayashi, and S. Seto, “How HIV Infected Haemophiliacs in Japan Were Informed of Their HIV-positive Status.” AIDS Care 14(5) (2002): 651–64.

23 Thomasina Borkman, “Self-help Groups at the Turning Point: Emerging Egalitarian Alliances with the Formal Health Care System?” American Journal of Community Psychology 18 (1990): 321-32.

24 Christensen 2010, Borkman 1990.

25 Personal communication July 2011.

26 Hirofumi Monobe et al., ‘Shougakkou ni okeru sei kyouiku no jirei kenkyu: HIV kansen yobou no tame ni shougakkou dankai ni okeru sei kyouiku” [A case study of sex education in an elementary school: sex education at the elementary school level for the prevention of HIV], Yokohama kokuritsu daigaku 2006: 239-48.

27 Cheryl Mattingly, Healing Dramas and Clinical Plots: The Narrative Structure of Experience (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

28 Christine R. Yano, Tears of Longing (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002).

29 I used the actual names of the organizations, per requests from those organizations.

30 I use the actual names of professionals, per their requests. Names of yōseishaare either pseudonyms they themselves use when speaking in public (full names), or author-assigned pseudonyms (known by an initial).

31 The Life Foundation was started in 1983 by sexologists and epidemiologists who recognized HIV would become a problem in Hawai’i due to the transience of the population and its relatively large gay population.

32 “The Life Foundation Homepage,” last updated 2015. http://lifefoundationhawaii.org.

33 The buddy system pairs people who have been recently diagnosed with HIV with a “buddy” who has been living with the diagnosis for some time and is comfortable acting as a mentor. It is similar to the sponsor model of Alcoholics Anonymous.

34 Personal communication, September 2011.

35 “Place Tokyo Homepage,” last modified 2016. http://www.ptokyo.org/.

36 Personal communication December 2010. Translation from the Japanese by the author.

37 Ikegami and Ikushima 2005.

38 Harumi Befu, Hegemony of Homogeneity: An Anthropological Analysis of ‘Nihonjinron’ (Portland: Trans Pacific Press, 2001).

39 Personal communication December 2010.

40 Personal communication December 2010, translation by author. Note: Ms. Ikegami’s assertions are based on research conducted by Place Tokyo.

41 Names are as they appear in the booklet. Translation by author.

42 Ikegami and Ikushima 2005, 6.

43 Personal communication July 2011.

44 Mother-to-child transmission in Japan is very low because pregnant women are screened and treated. Infection through intravenous drug use is also low because this type of drug use is relatively low in Japan.

45 Ikegami and Ikushima 2005, 8.

46 Personal communication August 2011.

47 This is a very common statement amongst yōseisha. All of my HIV positive interviewees emphasized this when they spoke with me, and the men who spoke at the AIDS Bunka Forum in Kyoto said it, too. They emphasized that similar things may have happened to them and that some may have commonalities, but were careful to say that everyone is different and that no one person’s voice could represent everyone with HIV.

48 In this particular case, getting HIV through being tattooed is probably less stigmatizing than getting HIV through sex or drug use but still more than stigmatizing than being infected through medical treatment because of the association between tattoos and the yakuza.

49 Interestingly, she did not discuss disclosure to her partner and did not discuss him during her talk.

50 Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Garden City: Doubleday, 1959).

51 Runestad 2010.

52 This term literally means “person of society” and is used to refer to someone who is living in and contributing to society by working, being married, and having children. For many, being chronically ill suggests that one cannot be a shakaijin. Failing to contribute to society in these ways, particularly for women, is considered by conservatives as selfish and wasteful – especially if one contracted a ‘bad’ illness like HIV through ‘deviant behavior.’

53 Similar strategies were also apparent at the AIDS Bunka Forum in Kyoto, where three male yōseisha spoke at a similar type of session with a moderator. There were, however, major differences between the two sessions. First, the Kyoto session was clearly not as scripted as the Yokohama session, and yōseisha were clearly more comfortable speaking for themselves. Second, the moderator was not a medical doctor and his role was solely to ask the pre-determined questions. Third, yōseisha at the Kyoto session were eager to speak to audience members individually: in fact, this is how I made a number of contacts. This just goes to show that each session is really managed to a different level depending on the participants.

54 Arthur Kleinman, The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing and the Human Condition (New York: Basic Books, 1988).

55 PLANET stands for People Living with AIDS NETwork. The A is generally written so that it also looks like an H to emphasis life with both HIV/AIDS. Unlike Place Tokyo, this group doesn’t do research and they don’t have an office – it exists IN people, and through the events like AIDS walks and participation at the Bunka Forum.

56 PLANET has been doing AIDS walks in May annually since 1991. They always follow the same route. The goals of the PLANET Candle Parade are to remember those who were lost to AIDS, raise awareness about HIV/AIDS, and to fight to end discrimination of those living with HIV/AIDS.

57 Ms. Odagiri keeps records of all the business along the parade route and which ones agree to display a red ribbon. When distributing red ribbons, she reminds store owners who have hung them in the past of this, and she points out which neighbors have agreed to display them. From year to year, one-third to one-fourth of the shops on the route agree to display red ribbons.

58 It’s not really possible to ascertain a participant’s HIV status unless, like in Hunky’s case, it’s literally written on their clothing.

59 Mattingly 2008, 74.

60 Ibid., 76.

61 Personal communication September 2011.

Bibliography

Allison, Anne. Nightwork: Sexuality, Pleasure, and Corporate Masculinity in a Tokyo Hostess Club. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Befu, Harumi. Hegemony of Homogeneity: An Anthropological Analysis of ‘Nihonjinron.’ Portland: Trans Pacific Press, 2001).

Borkman, Thomasina. “Self-help Groups at the Turning Point: Emerging Egalitarian Alliances with the Formal Health Care System?” American Journal of Community Psychology 18 (1990): 321-32.

Ikegami Chizuko and Ikushima Yuzuru, eds. Living Together: Our Stories. Tokyo: Place Tokyo, 2005.

Christensen, Paul. “Struggles with Sobriety: Alcoholics Anonymous Membership in Japan,” Ethnology 49 (2010): 45-60.

Cullinane, Joanne. “The Domestication of AIDS: Stigma, Gender, and the Body Politic in Japan,” Medical Anthropology 26 (2007): 255-292.

Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City: Doubleday, 1959.

Jurecic, Ann. Illness as Narrative. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

Kleinman, Arthur. The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing and the Human Condition. New York: Basic Books, 1988.

Orpett Long, Susan. Final Days: Japanese Culture and Choice at the End of Life. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005.

Mattingly, Cheryl. Healing Dramas and Clinical Plots: The Narrative Structure of Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Mattingly, Cheryl and Linda Garro. Narrative and the Cultural Constructions of Illness and Healing. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Miller, Elizabeth. "What’s In a Condom? HIV and Sexual Politics in Japan,” Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 26 (2002): 1-32.

McCall, Melanie L. “Aids Quarantine Law in the International Community: Health and Safety Measures or Human Rights Violations?” Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Journal 15(4): 1001–1028.

Monobe Hirofumi et al., "Shougakkou ni okeru sei kyouiku no jirei kenkyu: HIV kansen yobou no tame ni shougakkou dankai ni okeru sei kyouiku” [A case study of sex education in an elementary school: sex education at the elementary school level for the prevention of HIV], Yokohama kokuritsu daigaku 2006: 239-48.

Ochs, Elinor and Lisa L. Capps. “Narrating the Self,” Annual Review of Anthropology 25 (1996): 20.

“Place Tokyo Homepage,” last modified 2016 http://www.ptokyo.org/.

Rivers, W.H.R. Medicine, Magic, and Religion: The Fitz Patrick Lectures Delivered before the Royal College of Physicians of London in 1915 and 1916. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd., 1924.

Runestad, Pamela. “What People Think Matters: The Relationship Between Perceptions and Epidemiology in the Japanese HIV Epidemic,” International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences 5 (2010): 331-43.