Volume XIV, No. 1: Fall 2016

Kitchen as Classroom: Domestic Science in Philippine Bureau of Education Magazines, 1906-1932

REFERENCES | AUTHOR BIO | ![]() Download this Article as a PDF file

Download this Article as a PDF file

When citing this article, please refer to the PDF which includes page numbers.

Abstract: From 1906 to 1932, the Philippine Bureau of Education published three official magazines that explained the objectives of the American-run public schools. This article explores how Philippine Education, Philippine Craftsman, and Philippine Public Schools described the introduction and the teaching of domestic science during this period. It intervenes in previous scholarship on Philippine domestic science, the Filipina feminine ideal, and the efficacy and language of official texts in the public schools. Ultimately, it argues four contradictions about domestic science emerge in the magazines: 1) a lack of opportunity for the Filipina despite promises of expanding their role in society; 2) an inability to convince poorer, older Filipinos to change despite the hubristic belief in adoption by all; 3) a belief in the physical and mental limitations of Filipino people despite promises to improve Filipino bodies and lives; and 4) a cyclical promotion of western superiority that created a demand for imported goods while simultaneously paying for these items by selling western foods. Domestic science certainly strengthened and healed bodies in the Philippines, and it absolutely attempted widespread cultural change. Yet it ultimately was a practice for making food into an everyday reminder of American cultural hegemony in the Philippines.

Key Words: Philippines, Filipinas, American colonial, education, publications, food, foodways, diet, domestic science

This paper explores the contradictory messages on domestic science from three magazines published by the Philippine Bureau of Education between 1906 and 1932. Philippine Education, Philippine Craftsman, and Philippine Public Schools explained official educational pedagogy and policy to teachers and administrators throughout the Philippines, and each described the challenges of introducing domestic science to classrooms and communities. Inspired by Progressive Era American ideals and successes in the US, the Bureau of Education’s magazines regularly offered guidelines, testimonials, lesson plans, and advice for the application of domestic science in the Philippines. Yet they contradicted themselves and the ideals of domestic science.

A close examination of the Bureau of Education’s official magazines reveals four significant contradictions. First, they promoted domestic science as a tool for enlarging the role of Filipinas in society. But the magazines presented domestic science goals that reinforced the subservient position of Filipinas to Filipino men. Instead of expanding women’s opportunities outside of the home, the magazines presented a version of domestic science that limited self-expression and civic engagement to the kitchen. Second, the magazines claimed domestic science recipes and procedures would appeal to all Filipinos. They predicted domestic science’s message of modernity and improvement would guarantee an easy sell to rich and poor, young and old. But the magazines also acknowledged that some Filipinos found western recipes and ingredients too expensive, and others simply shied away from foreign and unfamiliar foods. Third, the magazines repeatedly claimed the higher nutrition and cleanliness standards of domestic science would strengthen Filipino bodies and improve Filipino lives. But their discourse also contained paternalistic assessments of the physical and mental limitations of Filipinos, revealing the racial prejudices of their authors and the hypocrisy of their promises. Finally, the magazines based their promotion of domestic science on the supposed superiority of American cuisine and culture. Yet they also conceded that in order to purchase imported western goods, Filipinas ironically needed to sell exportable arts and crafts, or sell foods that they learned to prepare in their domestic science classes. Together, these contradictions revealed how advocates struggled to introduce domestic science to the Philippines. They had hoped to replicate the changes that domestic science brought to the US. Instead, these publications demonstrate conflicting impulses within the Bureau of Education about the shape and scope of domestic science in the Philippines, as well as the most effective way to teach domestic science to a diverse and disparate population.

A close examination of the Bureau of Education’s official magazines reveals four significant contradictions. First, they promoted domestic science as a tool for enlarging the role of Filipinas in society. But the magazines presented domestic science goals that reinforced the subservient position of Filipinas to Filipino men. Instead of expanding women’s opportunities outside of the home, the magazines presented a version of domestic science that limited self-expression and civic engagement to the kitchen. Second, the magazines claimed domestic science recipes and procedures would appeal to all Filipinos. They predicted domestic science’s message of modernity and improvement would guarantee an easy sell to rich and poor, young and old. But the magazines also acknowledged that some Filipinos found western recipes and ingredients too expensive, and others simply shied away from foreign and unfamiliar foods. Third, the magazines repeatedly claimed the higher nutrition and cleanliness standards of domestic science would strengthen Filipino bodies and improve Filipino lives. But their discourse also contained paternalistic assessments of the physical and mental limitations of Filipinos, revealing the racial prejudices of their authors and the hypocrisy of their promises. Finally, the magazines based their promotion of domestic science on the supposed superiority of American cuisine and culture. Yet they also conceded that in order to purchase imported western goods, Filipinas ironically needed to sell exportable arts and crafts, or sell foods that they learned to prepare in their domestic science classes. Together, these contradictions revealed how advocates struggled to introduce domestic science to the Philippines. They had hoped to replicate the changes that domestic science brought to the US. Instead, these publications demonstrate conflicting impulses within the Bureau of Education about the shape and scope of domestic science in the Philippines, as well as the most effective way to teach domestic science to a diverse and disparate population.

Note on Sources and Historiography

Before examining the magazines, it is helpful to contextualize the era and authorship of their publication. Philippine Education, Philippine Craftsman, and Philippine Public Schools were the three most widely distributed monthly magazines of the Philippine Bureau of Education, the government organization in charge of the public school system. Formed in 1901, the Bureau of Education replaced the temporary educational system that the United States Army erected after the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898.1 Because the Philippines was a colony of the United States until 1942, Americans administered the Bureau of Education and introduced policies on race and pedagogy popular among Progressive Era American educators. They modeled much of their approach to teaching in the Philippines on the domestic science, vocational, and trade education at Native American boarding schools and African American vocational schools.2 Coordinating and updating these policies across the archipelago required the continuous distribution of information to teachers. The Bureau released its own official documents in the form of bulletins and circulars. But these three magazines were more approachable because they featured long essays, detailed photographs and illustrations, and news about fellow teachers. The oldest and longest running of the magazines was Philippine Education. From 1906 until 1926, Philippine Education shared a wealth of information for teachers such as personal announcements, administrative policies, book reviews, recaps of teaching conferences, administrative policies, lesson plans, and classroom accounts. Its successor, Philippine Public Schools, appeared from 1928 to 1932 and primarily released lesson plans. It was easily the most technical of the three magazines and because of its later publication run, it featured the most Filipino authors. By contrast, Philippine Craftsman contained longer pieces, more advertisements, and high quality artwork that made it more like a popular magazine than an educational journal; it had a shorter run from 1912 to 1917.

This paper also builds upon the scholarship of three distinct fields on the American Period (1898-1946) in the Philippines: domestic science, the feminine ideal, and textbooks. By focusing on the Bureau’s magazine articles on domestic science, the piece places these different bodies of scholarship that rarely interact with each other in conversation. For example, most scholarship on Philippine domestic science has focused on two approaches: First, that of domestic science as a lens for examining technology and modernity, or the successful cultivation by American teachers, businessmen, and government officials to equate kitchen technology with prestige, status, cosmopolitanism, modernity, and urbanity.3 Second, scholars have also viewed domestic science as a lens for atomizing the larger obsession with disease, health, and race in the age of empire, placing kitchens as the first line of defense against the weakening of Filipino bodies.4 In a more general sense, most studies on Philippine domestic science largely ignore the impact of American imperialism on Filipino cuisine, choosing instead to focus on the impact of trade with China or the three centuries of colonialism under Spain.5 City planning and urban studies scholars have tangentially touched on domestic science as well, focusing on the improvements of infrastructure and their effect on Philippine food systems.6 But relatively little work has been done on the debates about teaching domestic science in the public schools. This lack of study on educational dialogue is all the more surprising considering the wealth of scholarship on Philippine Public Schools and their promotion of American ideals through literature.7 A cottage industry on the Thomasites, the first American teachers in the Philippines in 1901, has repeatedly drawn the connection between education and American missionary work.8 Scholars have even examined the irony that promoting allegiance to the American empire in Philippine schools actually fueled Filipino nationalism and independence.9 Understanding the Bureau of Education’s promotion of domestic science is especially important because American reformers viewed the discipline as an effective tool for individual self-empowerment, social uplift, and the advancement of women.10 Scholarship on the connection between domestic science and the Filipina ideal has mostly focused on white American female missionaries teaching Filipinas the basics of home economics and housewifery.11 Even if this interpretation made Filipinas secondary actors in the narrative, at least they were closer to economic and political power during the American Period than the three preceding centuries under the Spanish when Filipino men relegated Filipinas to the sidelines of revolutionary movements.12 Debates about domestic science in the Bureau of Education magazines revealed that the Americans, too, questioned whether they could truly expand the role of Filipinas from the home into substantial civic power. Finally, this article builds on the scholarship of Filipino textbook literature. Scholars have examined how the Bureau’s standardized texts promoted American civic ideals while simultaneously weaving a narrative of stunted Filipino historical progress, justifying American imperialism.13 Yet there has been little scholarship on the Bureau’s magazines. Mindful of this previous work, this article examines how the Bureau’s magazines debated the role of domestic science in transforming how people ate, how Filipinas viewed their own role in society, and how teachers used texts in the classroom.

In the minds of these educators, the first priority of domestic science was convincing generations of Filipina schoolgirls that these methods could improve their lives. But many writers in the Bureau’s magazines claimed that improvement was incremental at best.

Promise and Limits for the Filipina

The Bureau’s magazines repeatedly claimed domestic science would open up new opportunities for generations of Filipina schoolgirls. They presented cooking, cleaning, and housekeeping as ways of figuratively contributing to the nascent Philippine democracy. Yet a close examination of these magazines shows that domestic science quite literally meant Filipinas would remain in subservient positions to Filipino men. Furthermore, domestic science created an even stronger tie to the home for the Filipina.

Many authors connected specific characteristics of the Filipina ideal to domestic science. These descriptions built upon the Spanish Period Filipina ideal, a set of activities which historian Marya Camacho says was intended “to prepare girls and women for their primary social function of spouse-mother-homemaker or, to a lesser extent, for religious community life” with “new feminine values with emphasis on purity, modesty, and seclusion.”14 Domestic science in the American Period, by contrast, promised to expand the available routes for Filipinas. For example, Silva M. Breckner wrote in Philippine Craftsman in 1914 that domestic science empowered Filipinas to take care of their own children, freeing them from the need for nursemaids and caregivers. She cited the story of a young Filipina mother who had previously taught domestic science but was now an empowered, self-reliant mother. “She has no one to care for her baby and wants no one, for she knows how to take care of it herself.”15 Two years later, Genoveva Llamas wrote in Philippine Craftsman that women were preconditioned to be better at home management than men. Filipina women thus had a duty to apply their innate skills for the betterment of their communities and Philippine society. She claimed women “use better judgment in buying things for the house,” “employ a greater variety of food,” “use better taste in the choice and arrangement of home decorations,” and “have learned to take care of the babies, a matter that is sure to raise the standard of vitality throughout the Islands.”16 These natural abilities bound women to the home. Llamas also encouraged Filipinas to perform their domestic duties with grace by replacing the drudgery of home management with a noble sense of national purpose. “To the one who ennobles the task and performs it with becoming dignity, it is a source of real pleasure and a means to health for herself and those around her.”17 Maria Paz Mendoza-Guazon, a Filipina professor of pathology and bacteriology at the University of the Philippines, elevated the importance of domestic science in The Development and Progress of Filipino Women (1928), a book endorsed by the Bureau of Education. Mendoza-Guazon claimed domestic science contributed to town life and the sense of community. “We can judge how charity has been firmly implanted into the heart of the Filipino woman and how much she has contributed, with her cookies and home-made cooking, to the entertainment of the people of the town where she was born.”18 She argued that exceptional Filipinas had drastically changed the definition of the Filipina ideal as well. “The Filipino woman of the modern type cares less for flattery, but demands more respect; she prefers to be considered a human being, capable of helping in the progress of humanity, rather than to be looked upon as a doll, of muscles and bones.”19 Mendoza-Guazon asserted that education also helped Filipino men to better appreciate Filipinas, daring to believe education also forced Filipino men to consider gender equality. “Higher education erases the difference of interests, aims, and views of men and women, and demands recognition of equal rights for both.”20 For these proponents, domestic science started a process of empowerment—first in the kitchen, then outside the home—that culminated in reducing gender inequality in Philippine society.

Yet a closer look at the education of Filipina schoolgirls shows domestic science was the only subject where many Filipina schoolgirls felt they could be creative and empowered at school. Multiple Bureau magazines described how Filipina schoolgirls took risks in classroom kitchens, but they did not voice the same enthusiasm in other subjects. In other words, the kitchen was the only place for change. Breckner offered apocryphal evidence that her fourth-graders in Tarlac and Palawan were noticeably different on the days they had domestic science. “The days when they are to have their cooking lessons are their happiest days. They sometimes tell me that they get something good to eat at that time.”21 She herself was happiest when domestic science lessons made a direct impact on cooking at home. “One mother was delighted to have her daughter make hoecake to eat with fried meat. She prized it as a choice dish. If our cooking is done along right lines it will interest the mothers.”22 Another American educator praised domestic science classes for allowing Filipinas to practice originality and friendly competition. Hugo H. Miller, the Chief of the Industrial Division for the Bureau of Education, wrote in Philippine Craftsman in 1914 that domestic science helped Filipina schoolgirls find their own voices and develop a stomach for criticism. “If one of our girls suggests a recipe (and there is quite a rivalry in this) she is given the opportunity of preparing it for the class; and when it is served, judgment is passed. The recipe may be rejected as not conforming to the best rules for diet, or may be accepted as presented, or altered to suit the class criticisms.”23 Domestic science classrooms measured success according to food. A Filipina could start to find her identity through the creation, competition, and the judgment of her peers.

But connecting individual pride to food was a subtle way of equating a Filipina’s importance in society to her ability to feed and please Filipino men. This was a view Philippine Public Schools asserted that it was the responsibility of Filipina schoolgirls to prepare ingredients from produce the boys had grown. This would give the boys a sense of their own importance while reinforcing the pleasing, subservient role of the girls. “When home-economics girls prepare and serve food to garden and poultry-club boys, the point is missed if the lesson is made simply an activity in feeding a large group…Whatever values may result, and there should be others, such an activity should not fail to bring the boys to understand and appreciate (in an elementary way) the food values of their garden products. It should acquaint them with the taste (if not the deliciousness) of the food, which may be a new vegetable or a common one prepared in a new way.”24 Domestic science instruction required Filipina schoolgirls to prepare dishes for Filipino schoolboys so that the boys would both eat the benefits of their own work and register the values of agricultural science; nowhere in this description is there a consideration of the work, values, or sacrifices of the Filipina. Domestic science may have empowered Filipina schoolgirls with new skills, but reinforcing their self-worth through food and demoting their voices in order to feed the boys was hardly an empowering experience. The role of women still largely meant preparing food and pleasing men.

Proponents of domestic science, however, were confident that more than just students would end up eating western dishes. They envisioned Filipinos of all ages ultimately embracing western cuisine and culture. Yet the Bureau’s magazines also debated the true breadth of adoption of domestic science, as many authors argued their efforts ignored or excluded the poor and the elderly.

Appeal and Underwhelming Adoption

The Bureau’s magazines insisted domestic science would entice Filipinos regardless of class or location. With pragmatic benefits to health, as well as aspirational promises of better lives, many authors argued Filipinos would embrace American dishes and food methods. Yet their promotion of domestic science overlooked a few factors. First, imported ingredients in western recipes were too expensive for many Filipinos. Second, some Filipinos simply liked the foods they had always eaten and resisted change. Authors in the Bureau’s magazines disagreed on the best way to promote domestic science in the future and to overcome these obstacles to change.

For some authors, domestic science was synonymous with the modern progress of the Philippines. As Miller wrote, “what can be more important to a home-loving people, as are the Filipinos, than improvement in home conditions!”25 Miller and others believed social improvement began at home, and domestic science was the key to home improvement—particularly for a population that was just learning western standards of cleanliness and hygiene. Connecting civilization to health, or elevating cleanliness to the level of godliness, had completely transformed the importance of domestic science in Native American and African American schools in the US; these precedents served as a model for teaching domestic science in the American-run Philippine public schools.26 George Kindly, an American teacher in Lumbago, made this connection explicit by quoting former president Theodore Roosevelt’s words on Native Americans in 1914 in Philippine Craftsman: “The girl should be taught domestic science, not as it would be practiced in a first-class hotel or a wealthy private home, but as she must practice it in a hut with no conveniences, and with intervals of sheep-herding.”27 Inspired by Roosevelt’s words, the Bureau’s teachers sought the best way to promote western cuisine and cleanliness to Filipinos. Breckner believed Filipinos would respond best to humility, arguing Filipinos would listen to new ideas if the Americans were humble. “Sometimes I have been led to wonder whether some American teachers do not lack in real sympathy with our educational problem, in that we too often go at our work in the spirit that drives rather than leads…[Filipinos] should see in us and our ‘customs’ ways which we would want them to imitate.”28 Breckner also believed Filipinos would pay attention if Americans demonstrated the best practices and behaviors of domestic science. “We can do as much in teaching by our example and manner as we can by words alone.”29 In Breckner’s eyes, seeing earnest Americans practice domestic science would be an irresistible lure for many Filipinos.

Other American educators believed community outreach would win over Filipinos. While teachers could proselytize to Filipina schoolgirls, there were skeptics in the community that domestic science advocates needed to convince. Llamas encouraged teachers to welcome older Filipinos into their kitchen classrooms to see domestic science for themselves. “Opposition to innovations is often overcome by inviting the old folks to visit the school and get in touch with housekeeping as there taught. If step by step is explained to them and the finished product in cooking is sampled or taken home, clearer ideas of the Bureau’s point of view will be obtained.”30 She argued that older Filipinos were even more important than Filipina schoolgirls because families ultimately shaped everyday Philippine life. “Not only daughters but parents ought to be trained in domestic science, for upon them rests the happiness and prosperity of the home.”31 The Bureau’s magazines believed they could win over Filipinos by bringing domestic science demonstrations into the home. Reinforcing classroom concepts when cooking at home would spread knowledge to non-students, and it would free up time in the classroom. Students, parents, and teachers would all benefit. Philippine Public Schools in 1931 described how this scenario would help teachers. “If home activities soon followed, if they were closely connected with classroom activities, and if some satisfactory device were worked out for giving a girl help and credit or at least recognition for preparing and serving at home recipes ones prepared in class, considerable school time now spent in ‘practice’ of simple techniques could be saved for purposes more profitable in the education of the girl.”32 Ideally, teachers would convert both young and old Filipinos behind domestic science simply through exposure.

The most popular message in the Bureau’s magazines to convince Filipinos to cook and eat like Americans, however, was the appeal to science. Public outreach and promises of progress were good, but hard evidence in the form of nutritional science would supposedly win over Filipinos with objective truth. Nutritional science would also disabuse Filipinos of antiquated superstitions about food that actually did more harm than good. Elvessa A. Stewart, an American who taught in the Philippines from 1912 to 1957, asserted in a 1929 article in Philippine Public Schools that “Scientific reading is the mortal enemy of superstition…Such false beliefs as ‘that fruit may not be eaten for breakfast because it will give a stomach ache’ or ‘that milk is not the proper for people beyond infancy’ have no basis in fact and must be overcome before we can reach the goal of optimal nutrition which will help make vital health a reality instead of an ideal.”33 Stewart also believed developing a thorough understanding of nutritional science in the present would have long-term benefits in the future. Educators needed to make nutritional science literature easily accessible in schools. “Every library, whether the library of the school or the private library of the teacher, should be supplied with this material.”34 Similarly, Philippine Public Schools argued in 1928 that if a Filipina schoolgirl understood the theory behind nutritional science, she would continue applying domestic science methods for the rest of her life. “She has enough training in manipulation that if in later years she may have reasons to do more extensive work in cooking she will be able, after some practice, to prepare a meal that is well-balanced and palatable and satisfactory in every way.”35 Science would win over the skeptics and implant itself into the Philippine future.

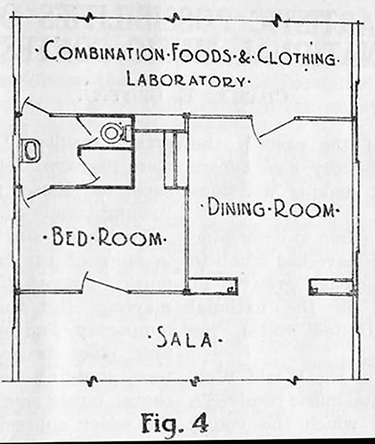

Other Americans argued that the way to convince Filipinos to adopt domestic science was to show them the wonders of a modern classroom kitchen. Domestic science stressed order, hygiene, and cleanliness in physical space, resulting in school kitchens unlike those in most Filipino homes. They emulated domestic science kitchens in the US with multi-purpose spaces for sewing and studying as well as cooking. These classroom kitchens featured chimneys that funneled smoke out of the house, as well as low hoods with ventilators because, as Philippine Public Schools wrote in 1931, “a class cannot do its best work in a smoky room.”36 Carrie L. Hurst boasted about her space in Misamis in Philippine Education in 1907. She had the best building on campus because it featured a fresh coat of white paint, eight white curtains at the windows, a light colored wooden cupboard, and a small linen closet ingeniously fashioned from discarded soap and milk boxes. Together, they created what she described as “quite a ‘homey’ feeling when our table is set and we are partaking of a meal prepared in our own kitchen.”37 Philippine Public Schools noted in 1928 that classroom kitchens were designed with “working quarters and conditions which are as nearly as possible like a model home,” with the intention of inspiring Filipina schoolgirls to recreate these spaces at home.38 If they could maintain the same standards of the classroom in their kitchens at home, they would practice domestic science throughout their lives.

This praise for Philippine classroom kitchens inevitably inspired many Bureau magazines to critique the average Filipino home kitchen. Critics such as Llamas blamed the shoddy state of Philippine home kitchens on the lack of attention to sanitation and hygiene during the Spanish Period. “Before the coming of the Americans, the sanitary system was so poorly organized that thousands of people died every year from preventable diseases. People knew little of importance of cleanliness.”39 Mendoza-Guazon also deplored the omnipresence of smoke and dirt in Philippine kitchens, even in the homes of the elite. She recounted how cooks prepared banquet meals in modest, dirty kitchens. “As there was no gas range, an iron oven or, in many instances, the earthen ovens or kalan were lined on top of a long wooden table with strong legs.”40 Furthermore, Miller lamented that the average Filipino kitchen was “not sufficiently planned for in the mind of the house builders” and was “cramped and ill-equipped and impossible to clean.”41 Naturally, seeing what was possible in classroom kitchens would inspire Filipinos to adopt domestic science – spaces, dishes, ingredients, customs, and all.

Although the Bureau’s magazines maintained a rosy belief that the adoption of domestic science was inevitable, they also conceded some of their own promotion had backfired. Indeed, Philippine Public Schools wrote that some of the procedures of western domestic science were ill suited for the Philippines. In 1928, Philippine Public Schools claimed the obsession with technology of domestic science had caused some Filipinos to decrease their consumption of fresh fruits. “Fresh fruits not only are cheaper than canned ones but they also have greater nutritive value,” it said. “Canning should be confined to seasonal fruits which are in such abundance that all cannot be used while in season.”42 Philippine Public Schools also argued that Filipinos were consuming too many imported foods instead of healthier, indigenous alternatives; celebrating imported canned goods in Bureau promotional literature and photographs perpetuated unhealthy habits. “A picture showing an elementary cooking class working at a table which has on it bottles of mixed pickles, catsup, and other sauces illustrates a wrong idea of plain elementary cooking. These ingredients are expensive and add little to the diet.”43 Filipinos were readily adopting western domestic science, but they were adopting the less nutritionally valuable aspects of it.

But the biggest hurdle to the widespread adoption of domestic science was the price of imported western ingredients. Items such as canned milk were simply too expensive for many Filipinos, despite their supposed health benefits. The Bureau’s magazines repeatedly claimed that canned cow’s milk was superior to indigenous milk sources such as carabao (water buffalo) milk and coconut milk. Eusebio B. Salud even connected western milk consumption to the progress of western civilization: “The achievement of any race of people in science, art, and literature depends more on the milk consumption of that people than on any factor…a nation that consumes milk liberally is bound to be a healthy, virile, and prosperous nation.”44 He also highlighted the importance of milk in child development. “The children who drank milk showed, in general, brighter faces and were more active at play than those of the control group who had no milk.”45 Other milk advocates explicitly connected the increase in milk consumption in public schools to domestic science. José C. Munoz, a supervising teacher in Negros Occidental, stated that teachers had a direct impact on the popularity of cow’s milk. “Of course the teachers’ influence over the children has had something to do with this change of attitude toward milk…Records now show that sixty percent of the pupils in the central school drank milk. Less than ten percent drank milk last July.”46 The Bureau’s magazines made imported canned milk synonymous with better nutrition and healthy bodies, even though it was an item many Filipinos could barely afford. Munoz himself describes how milk was an aspirational product. “Desires for the good of our health must be met…When the need for milk is finally realized, the people will always provide funds for this very important food.”47 Milk was an important but pricey ingredient that not everyone could afford.

The Bureau’s publications also described skepticism of domestic science among older Filipinos. In Cotabato, Anna Pinch Dworak complained that all of her work promoting domestic science in classrooms and public markets had ultimately made “little or no impression in the line of adoption of new dishes.”48 Miller similarly lamented that while students embraced domestic science, parents did not always follow suit. “Anything that has been made in the cooking classes has been eaten with relish,” he wrote, “but the results have evidently failed to penetrate the home. It is a matter of difficulty for one member of a family to cause a foreign food to become a part of the family’s diet.”49 Promises of progress, community outreach, and advances in science could neither put money in the pockets – nor remove the skepticism – of all Filipinos.

The Bureau’s magazines, however, also claimed domestic science would have tangible effects on Filipino bodies and minds. In another plea to win over Filipinos, the Bureau promised western foods would lead to stronger physiques and sharper thinking. Yet their claims of the inherent inferiority of Filipinos caused one to question whether these American authors even believed their own promises of domestic science’s effects on the opportunities available to Filipinos.

Bodies, Minds, and Race

The Bureau’s magazines also promoted domestic science by claiming western foods and health standards would strengthen Filipino bodies and better lives. But Bureau magazine articles undermined their own message by presenting a racist belief that many Americans held in the early-1900s – namely, that Filipinos were inherently weaker and less intelligent than white Americans. The same Bureau magazines that offered the promise of domestic science simultaneously mocked Filipinos as childlike, imitative, dependent on Americans, imitative, and incapable of complex thought. The Bureau’s perpetuation of these stereotypes made the goal of improving Filipino lives ring hollow.

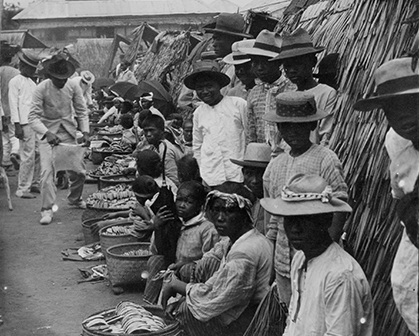

The Bureau’s magazines contended that western standards of domestic science would inevitably improve lives. Indeed, taming the tropics and improving Filipino resistance to disease became a main justification for American imperialism. Many authors claimed that domestic science, by bringing a higher standard of nutrition to a large number of Filipinos, would make for a healthier nation. Miller described how Filipina schoolgirls were adapting basic domestic science recipes for home use. “We have in all classes little kitchen lovers who develop their cooking into an art; but these must have individual training…We have learned that the dishes to which the girls are accustomed are cheap, and that a balanced diet may easily be evolved from them.”50 He stressed cleanliness was the most important value of domestic science food instruction. “Our work lies mainly in lessons of cleanliness, to have the girls form habits of preparing their dishes in a clean and wholesome way, basing their procedure on what they have learned concerning personal and household hygiene and sanitation.”51 Llamas reiterated the importance of bringing cleanliness to all Filipinos regardless of economic class. She criticized domestic science cookbooks for catering primarily to well-to-do families by featuring American recipes for preserved fruits and breads that were “seldom served at the Filipino table.”52 Llamas insisted that domestic science stress clean, nutritious foods drawn from both Filipino and American cuisines. “Whether Filipino or American dishes are served,” she wrote, “they are beginning to be served in the safest and the most healthful way.”53 Moreover, she believed the procedures of domestic science ought to carry over to the more humble Filipino dishes in the future because “the extravagance of imported foods is gradually giving way to the use of foods obtainable from the home markets or in the home garden.”54 For Stewart, the key to transforming health was convincing Filipinos to look at food as more than just fuel. “Just as health is more than mere freedom from disease, so nutrition is more than satisfying hunger of filling the stomach.”55 Llamas also believed domestic science classes were essential to eradicating germs and disease from cooking. “When the excellent interest shown in school cooking takes form and produces results as home cooking, an important problem will have been solved, and a long step will have been taken toward the elimination of the sale of poorly prepared food from germ-laden baskets on streets and in the market.”56

Most Bureau magazines agreed that school lunch counters were the most effective place to introduce this focus on cleanliness and improving Filipino bodies to the largest number of people. At public schools throughout the archipelago, Filipina schoolgirls sold the dishes they prepared in their domestic science classes to students, teachers, and the general public. Filipinos could eat at school lunch counters and sample the benefits of food that met western standards and was prepared under the watchful eyes of actual domestic science instructors. Multiple authors praised the food at school lunch counters as superior to the food at public market stalls. Florencia Bonifacio, a teacher at the Meisic School in Manila, mentioned the quality of her students’ cooking in Philippine Craftsman in 1915. “The food sold by the schools is prepared under the supervision of a trained domestic-science teacher and is served in dishes which are washed and scalded. All the pupils who prepare or handle food for sale are clean.”57 She remarked that this was a stark contrast to the food prepared in public market stalls because “the less one knows about the preparation of the food sold by the street vendors and the markets, the less difficult it is for him to eat it.”58 She used the example of cakes and ice cream to elaborate on the difference in quality between school lunch counters and public stalls. “The cakes made by the schools are much richer than those which can be bought at the shops. The ice or ice cream sold by the schools contains milk, while that sold by the street vendors is made of water and the white of eggs.”59 There simply was no comparison. Munoz claimed Filipino parents also preferred that their children eat at school lunch counters instead of market stalls. “They were glad that a good substitute was found at last for the dirty cakes and candies that are usually sold on the road by local vendors.”60 School lunch counters were serving meals that met the standards of western domestic science, not the suspect imitations that failed to strengthen bodies and minds. Munoz also boasted that school lunch programs led to a sharp decrease in the number of below-average pupils. Over the course of four months, he claimed meals from school lunch counters helped to lower the percentage of below average pupils from 65 percent in July to 42 percent.61 “The best result of the of school lunch program is the increase in grades and aptitude of the children.”62 With proper nourishment, Filipino students could focus on their studies and prepare themselves for better opportunities in the future.

School lunch counters also had an additional benefit for Filipina schoolgirls of teaching them how to reinvest in their communities and how to run small businesses. Bonifacio described the joy Filipina school girls felt as they decided where to redirect the profits they earned selling food into purchasing athletic supplies, industrial material, and books for the school library.63 Other Filipina schoolgirls set up their own home catering businesses, selling their expertise in cooking many of the recipes they learned in their domestic science courses. Llamas praised a home caterer in Leyte who offered an impressive menu of domestic science staple items—sandwiches, biscuits, corn muffins, lye hominy, pickles, jams, jellies, fruit butters, cookies, gingerbread, layer and loaf cakes, doughnuts, ice cream, and candies.64 These catering businesses, by replicating the same high standards of domestic science classrooms, would expose the average Filipino to nutritious foods at affordable prices.

Nevertheless, the Bureau’s magazines also included plenty of passages that stated Filipinos were inherently weaker and less intelligent than whites. Considering the popularity of Social Darwinism and ethnology on conceptions of race in the early-twentieth century, it is not surprising that these views affected the writing of American Progressive reformers in the Philippines.65 These views shaped the thinking of a number of authors in the Bureau’s magazines. Edna A. Gerken wrote in Philippine Public Schools in 1930 that Americans should practice patience while Filipinos developed good nutritional habits and healthy bodies. “With persistent effort, the desired results in changed living habits will come even though it may not be evident until the present school child has become the parent in the home of tomorrow.”66 Llamas asserted a similarly benign belief in the adoption of domestic science by stating “housekeepers and cooks are not made in a single day, and experts in these lines find that a large measure of their success is the result of patient, persistent practice.”67 But others believed patience could not compensate for the innate physical and mental limitations of Filipinos. For example, Kilmer O. Mos, an American teacher working in Central Luzon, wrote in Philippine Craftsman in 1914 that the men who were working Philippine fields were naturally weaker than the white pioneers who settled the American West. “The early pioneers in America had at least the advantage of having the work accomplished by strong, able-bodied men,” he wrote. In the Philippines, the work was done instead by “immature schoolboys” who “got discouraged and left” because “there was nothing stronger than a moral suasion to hold them.”68 W.J. Cushman, an American teacher at the Villar Settlement School, asserted in Philippine Craftsman in 1914 that Filipinos were incapable of helping themselves because they were immature and indecisive. “The Negrito is but a child and changes his mind with every change of the moon, if not oftener, and that change of mind may mean a change of location or something else just as detrimental to the best interests of the school.”69 With American help, Cushman claimed there was “a marked effect on the working capacity of the pupils…now it is possible to get quite satisfactory work out of the older pupils, at least ten to twelve times the amount accomplished at first.”70 American instruction—and diet—had supposedly made Filipinos surpass their natural abilities. Yet their ceiling of potential still lay within the inherent limitations of their race.

The supposed difference in physical and mental abilities between Filipinos and Americans was an expression of the belief in the superiority of the west. To convince Filipinos domestic science was worth adopting, the Bureau’s magazines encouraged teachers to repeat the narrative of western superiority in many ways.

Promotion of the West

Domestic science’s supposed advantages relied largely on promoting the superiority of western cuisine and culture. The Bureau’s magazines included plenty of accounts claiming domestic science originated from countries with higher standards of cleanliness and sophistication. Connecting western foods with cultural superiority thus developed a desire for imported goods among Filipinos. But the Bureau’s magazines also pointed out that Filipina schoolgirls paid for western goods either by making traditional Filipino arts and crafts for export, or by selling food within their communities. Thus, domestic science in the Philippines perpetuated the East-West dichotomy both by creating consumer demand for western goods among Filipina schoolgirls, and by supplying foods catering to Filipino communities. Domestic science thus consistently elevated western cuisine to Filipinos and caught them in a cycle of producing and consuming western foods.

Many domestic science instructors reinforced the supposed superiority of western food by making Filipina schoolgirls prepare banquets of western dishes on special occasions. The Bureau’s magazines recounted how public schools around the country welcomed visiting government bureaucrats and dignitaries with meals demonstrating a command of domestic science. Hurst wrote that her students prepared elaborate meals for Governor General James F. Smith. “The girls entertained several times at luncheon and dinner, setting the table, cooking, and serving as well as many more experienced people.”71 She praised her students for adapting basic domestic science recipes to their specific locale because “they seem to have mastered the art of good cake baking to the extent of taking any new recipe and adjusting it to suit the conditions here.”72 Similarly, Alice M. Fuller, the Bureau’s national director of domestic science, praised students who prepared western recipes in Cagayan Province. She listed an impressive set of dishes that her students prepared in Philippine Education in 1907. For lunch, they made hot cakes with melted sugar and coffee; and for dinner, they made arroz Valencia, lettuce salad, beets from the school garden, and dessert of biscuit doughnuts, and fudge.73 Visitors were so impressed with the meal that Fuller boasted, “some members asked that we might have such a dinner each year and this proposition was greeted with great enthusiasm.”74 Fuller then described a year later in Philippine Education that her students had mastered a range of western recipes that changed through the year. All year round, they were prepared tomato catsup, creamed cod fish, salmon croquettes, and coconut custards.75 During Christmas, they added coconut cream candy, penotchie, and lemon cream.76 Filipina schoolgirls prepared western foods that symbolized western sophistication in order to reassure American visitors that domestic science instruction was effective and that the civilizing influence of domestic science was reaching Filipinos around the country.

The most widely embraced cooking technique from domestic science was baking and the Bureau’s magazines were flush with accounts of Filipina schoolgirls making breads, cakes, and pastries. The magazines presented baking’s growing popularity as evidence of domestic science’s positive effect in the country. For example, Miller described how hot cakes and doughnuts were now available across the country. “They have achieved an almost complete invasion. No home is without them…In the local market you may purchase doughnuts ‘a la Americana’ from a woman who learned the art from her schoolgirl daughter.”77 He noted that the custom of taking tea in the afternoon had spread as well. “The serving of tea with sandwiches and biscuits has become quite common and invitations to five o’clock tea parties to celebrate birthdays among both girls and boys are to be expected at almost any time.”78 Llamas focused on the explosion of baked goods at Leyte High School. “It has been interesting to watch the trend of these lunches from doughnuts to peanut candy, which were about the only articles that had ready sale at the beginning of the year, to cookies, gingerbread, and cup cake, and later to biscuits and corn muffins, which at present time are popular.”79 Dworak mentioned about teaching Filipina Muslim schoolgirls in the southern islands how to bake at the Moro Girls Industrial School in Cotabato. “Bread is furnished for the early breakfast; rice and fish, dried as a rule, at 11 o’clock; and for supper a kind of stew made of fish and vegetables. Frequently the stew is supplemented by salmon or sardines.”80 She also boasted that the girls always finished their lunches, and that they ate better at school than at home because lunch “was well prepared and in abundant quantity.”81 The growth of baking was one of the proudest accomplishments of domestic science.

Some advertisements for western imported foods in the Bureau’s magazines attributed the growth of western cuisine in the Philippines to the supposedly higher standards of western canned goods. These ads claimed products from the US and Europe inherently had higher standards of cleanliness, hygiene, and nutrition. For example, a 1907 ad for Mellin’s Baby Formula in Philippine Education boasted it had won the prize for high quality and nutrition at the 1904 Saint Louis World’s Fair. The ad copy said Mellin’s excelled not only in the US, but was also better than conventional milk sources in the Philippines because “it is specially adapted for use where fresh milk is either unavailable or of doubtful quality.”82 The ad then appealed to an even wider audience by promising benefits for invalids and convalescents.83 Other magazine ads also focused on the variety of imported western food items. Armour’s Meat claimed Filipino consumers should crave different kinds of beef. “It is especially important to have variety, not only in the kind of meat but in the way it is served. Many people grow weary of sitting down day after day to fried, boiled, or roasted meats, until they declare ‘don’t care for meat.’”84 Different kinds of canned meats brought a variety of items that ensured consumers ate properly. Ads for restaurants in Manila also seized on the appeal of western cuisine. Philippine Education ran an ad for the Imperial Hotel in 1907 that boasted it served “The Best of Australian Meats and Butter” as well as a “First-class American Table-Board.”85 Trading on the supposed benefits of western cuisine only reinforced the importance of Filipinos embracing domestic science.

Yet in order to pay for the imported goods and ingredients, Filipina school girls resorted to creating arts and crafts for export, or selling prepared foods in their communities—thus using their domestic science skills to pay for domestic science demands. Filipina schoolgirls made trinkets as well as exportable high-priced commodities such as baskets, lace, and textiles that appealed to American consumers.86 Miller described how a Filipina schoolgirl used her domestic science training to pay for these purchases. “She has been taught in her domestic science class to crochet, embroider, or sew. She makes a pretty article and offers it for sale. With the money she received she learns that she has earning power.”87 Items beyond the kitchen appealed to her as well. “Formerly in our town a girl with shoes and stockings was very rare and girls cared little for such things,” wrote Miller. “Now they long for pretty shoes and stockings, a scarf, some other pretty article.”88 Domestic science classes enabled the Filipina to buy these items because “she needs no longer sit apathetically and long for pretty things that others wear…she can get many things which otherwise she would be compelled to do without.”89 Munoz stated that while domestic science had created a desire for imported items, it also encouraged Filipino families to raise money and increase their standard of living. “Another outstanding result that is bound to come on account of the school lunch is the raising of the standard of living and the encouragement of production and labor.”90 The desire for new products supposedly also drove their parents to work harder to afford these items, too. Munoz continued, “In a parent-teachers gathering held some time ago in connection with the mothers’ day celebration, an intelligent farmer and father of school children told me that his tenants were working hard to get money to buy [canned cow’s] milk for their children. To increase one’s earnings is a matter of desire.”91 Domestic science thus inspired both the purchase of imported western goods by Filipinas, as well as the labor to pay for their purchase. While not everyone could afford to buy these imported goods at first, the Bureau’s magazines promotion of domestic science both fueled and supported the determination to incorporate them into Philippine society end.

Conclusion

Examining Philippine Education, Philippine Craftsman, and Philippine Public Schools helps us understand how American cultural imperialism worked in the Philippines at the start of the twentieth century. With the amount of coverage these magazines devoted to domestic science, it is clear that the Bureau of Education viewed its dissemination as a priority for changing Philippine culture. Transforming how people ate would remind all Filipinos, regardless of economic class, geographic region, or religious faith, that an American system governed the archipelago from the bottom up.

Yet the differing views contained within these magazines also created contradictions that ultimately limited the spread of domestic science and the transformation of the Filipino diet. The inability to reach older generations, as well as the expensive price of imported ingredients, proved difficult hurdles for domestic science to overcome. Conflicting messages on achievable goals and ultimate objectives of domestic science made uniform implementation across the country impossible. Because domestic science largely consigned Filipina schoolgirls to the kitchen, the lofty promises of domestic science failed to resonate even with those it most directly targeted. These factors—along with others too numerous to discuss in this essay—resulted in the persistence of Filipino cuisine and, indeed, a decline in the consumption of American cuisine after the formal end of American colonialism in the Philippines in 1946.

Despite the failure of the Bureau to implement domestic science to the Philippines on a national scale, an examination of these magazines can reveal important insights into twentieth century Filipiniana. These magazines are rich cultural sources and records capturing the transmission of Progressive Era ideas from the US to the Philippines. They reflect the consumer habits and taste preferences of teachers, educators, and students for more than thirty years. As magazines published during the golden age of advertising and the rise of the Philippine popular press, they also illustrate the biases of their authors, as well as the aspirations of their Filipino students who they described. Disagreements within these magazines about the size and shape of domestic science showed a healthy and constructive debate about how to pitch messages that would resonate with newly educated Filipinos eager to perform an American-style middle class identity. Finally, these magazines reflected the importance the Bureau of Education placed on transforming future generations of Filipinos. Sharing approaches to domestic science that worked in different parts of the country meant teachers could read about examples that worked and emulate them in their own schools. After all, stories on domestic science shared space in these magazines with discussions about agricultural science, writing, economics, civics, politics, math, and arithmetic. These magazines made domestic science part of a Filipino student’s core curriculum regardless of whether he or she was destined for a future in classical, trade, or vocational education.

Most importantly, depending on one’s view, domestic science was either an insidious agent or a benevolent instruments of change. Whether one ate Filipino or American food, domestic science brought a new American frame to how one ate, cooked, and thought about one of the most basic human needs. Food thus became a subtle but unescapable expression of imperialism and the constant efforts at America’s constant efforts to enforce its cultural hegemony in the Philippines.

NOTES

1 Encarnación Alzona. A History of Education in the Philippines, 1565-1930. Manila: University of the Philippines Press, 1932.

2 Anne Paulet, “To Change the World: The Use of American Indian Education in the Philippines,” History of Education Quarterly 47, no. 2 (2007): 173–202.

3 Raquel A. G. Reyes. “Modernizing the Manileña: Technologies of Conspicuous Consumption for the Well-to-Do Woman, circa 1880s–1930s.” Modern Asian Studies 46, no. 1 (January 2012): 193–220.

4 Warwick Anderson. Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006; Ventura, Theresa. “Medicalizing Gutom: Hunger, Diet, and Beriberi during the American Period,” Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 63, no. 1 (2015): 39–69.

5 Felice Sta. María. The Governor-General’s Kitchen: Philippine Culinary Vignettes and Period Recipes, 1521-1935. Pasig City, Philippines: Published and exclusively distributed by Anvil, 2006.

6 Daniel F. Doeppers. Feeding Manila in Peace and War, 1850-1945, New Perspectives in Southeast Asian Studies (Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2016, 2016); Torres, Cristina Evangelista. The Americanization of Manila, 1898-1921 (Diliman, Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2010).

7 Meg Wesling. Empire’s Proxy American Literature and U.S. Imperialism in the Philippines. New York: New York University Press, 2011; McMahon, Jennifer M. Dead Stars: American and Philippine Literary Perspectives on the American Colonization of the Philippines. Diliman, Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2011.

8 Mary Racelis Hollnsteiner and Judy Celine A. Ick. Bearers of Benevolence: The Thomasites and Public Education in the Philippines. Pasig City, Philippines: Published and exclusively distributed by Anvil Pub, 2001; Sianturi, Dinah Roma. “‘Pedagogic Invasion’: The Thomasites in Occupied Philippines.” Kritika Kultura 0, no. 12 (2009): 26; Steinbock - Pratt, Sarah. “‘We Were All Robinson Crusoes’: American Women Teachers in the Philippines.” Women’s Studies 41, no. 4 (2012): 372–392; Villareal, Corazon D., Thelma E. Arambulo, Guillermo M. Pesigan, and American Studies Association Of The Philippines. International Conference And Annual Assembly. Back to the Future: Perspectives on the Thomasite Legacy to Philippine Education : Papers Presented at the International Conference and Annual Assembly of the American Studies Association of the Philippines, Ateneo de Manila University, Loyola Heights, Quezon City, August 24-25, 2001. Corazon D. Villareal, Editor ; Thelma E. Arambulo, Guillermo M. Pesigan, Associate Editors. Manila, American Studies Association of the Philippines in cooperation with the Cultural Affairs Office, U.S. Embassy, 2003.

9 Lisandro E. Claudio. “Beyond Colonial Miseducation: Internationalism and Deweyan Pedagogy in the American-Era Philippines.” Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 63, no. 2 (2015): 193–220.

10 Dolores Hayden, The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1981); Sarah Leavitt, From Catharine Beecher to Martha Stewart: A Cultural History of Domestic Advice (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Glenna Matthews, “Just a Housewife”: The Rise and Fall of Domesticity in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987); Phyllis M. Palmer, Domesticity and Dirt: Housewives and Domestic Servants in the United States, 1920-1945, Women in the Political Economy, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989.

11 Vicente L.Rafael. “Colonial Domesticity: White Women and the United States Rule in the Philippines.” American Literature 67, no. 4 (December 1995): 639–66.

12 Maria Luisa T. Camagay. Working Women of Manila in the 19th Century (Manila: University of the Philippines Press and the University Center for Women Studies, 1995); Reyes, Raquel A. G. Love, Passion and Patriotism : Sexuality and the Philippine Propaganda Movement, 1882-1892, Critical Dialogues in Southeast Asian Studies. Singapore: NUS Press ; Seattle, 2008.

13 Kenton J. Clymer. “Humanitarian Imperialism: David Prescott Barrows and the White Man’s Burden in the Philippines.” Pacific Historical Review 45, no. 4 (1976): 495–517; Goh, Daniel P. “States of Ethnography: Colonialism, Resistance, and Cultural Transcription in Malaya and the Philippines, 1890s-1930s.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 49, no. 1 (2007): 109–142; Hawkins, Michael. “Imperial Historicism and American Military Rule in the Philippines’ Muslim South.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 39, no. 3 (2008): 411–429; Raftery, Judith. “Textbook Wars: Governor-General James Francis Smith and the Protestant-Catholic Conflict in Public Education in the Philippines, 1904-1907.” History of Education Quarterly 38, no. 2 (1998): 143–64.

14 Marya Svetlana T. Camacho. “Woman’s Worth: The Concept of Virtue in the Education of Women in Spanish Colonial Philippines.” Philippine Studies 55, no. 1 (2007): 53.

15 Silva M. Breckner. “Our Domestic Science Work and Some of Its Results.” Philippine Craftsman 3, no. 5 (November 1914): 338.

16 Genoveva Llamas. “How the Teaching of Domestic Science Is Influencing the Home.” Philippine Craftsman 4, no. 8 (February 1916): 525.

17 Ibid., 609.

18 Maria Paz Mendoza-Guazon. The Development and Progress of the Filipino Women. Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1928: 32.

19 Ibid., 44.

20 Ibid., 46.

21 Breckner, “Our Domestic Science Work and Some of Its Results,” 338.

22 Ibid.

23 Hugo Herman Miller. “Results from Domestic Science.” Philippine Craftsman 2, no. 7 (January 1914): 444.

24 “Photographs for Publication Showing Home-Economics Activities.” Philippine Public Schools, February 1928, 28.

25 Miller, “Results from Domestic Science,” 441.

26 Anne Paulet. “To Change the World: The Use of American Indian Education in the Philippines.” History of Education Quarterly 47, no. 2 (2007): 173–202; Franklin, V. P. “Pan-African Connections, Transnational Education, Collective Cultural Capital, and Opportunities Industrialization Centers International.” The Journal of African-American History 96, no. 1 (2011): 44–61.

27 GeorgeKindley. “The Lumbayo Settlement Farm School.” Philippine Craftsman 2, no. 8 (February 1914): 564.

28 Breckner, “Our Domestic Science Work and Some of Its Results,” 335.

29 Ibid.

30 Llamas, “How the Teaching of Domestic Science Is Influencing the Home,” 523-524.

31 Ibid.

32 “Practice – For What?” Philippine Public Schools, August 1931, 272.

33 Elvessa A. Stewart. “Foods in Relation to Health.” Philippine Public Schools, November 1929, 371.

34 Ibid.

35 “Present Trends in Home Economics Instruction.” Philippine Public Schools, October 1928, 295.

36 “New Plans for Home-Economics Buildings.” Philippine Public Schools, November 1931, 397.

37 Carrie L. Hurst. “Domestic Science in Misamis Provincial High School.” Philippine Education 4, no. 6 (November 1907): 40.

38 “Present Trends in Home Economics Instruction,” 295.

39 Llamas, “How the Teaching of Domestic Science Is Influencing the Home,” 523.

40 Mendoza-Guazon, The Development and Progress of the Filipino Women, 23.

41 Miller, “Results from Domestic Science,” 442.

42 “Photographs for Publication Showing Home-Economics Activities,” Philippine Public Schools, February 1928, 27.

43 Ibid., 27.

44 Eusebio B. Salud. “A Milk-Feeding Experiment.” Philippine Public Schools, March 1930, 89.

45 Ibid.

46 Jose C. Munoz. “The Guihulngan School Lunch.” Philippine Public Schools, February 1930, 49–50.

47 Ibid., 50.

48 Anna Pinch Dworak. “The Cotabato Moro Girls Industrial School.” Philippine Craftsman 3, no. 9 (March 1915): 685-686.

49 Miller, “Results from Domestic Science,” 458.

50 Ibid., 442-3.

51 Ibid.

52 Llamas, “How the Teaching of Domestic Science Is Influencing the Home,” 522.

53 Ibid.

54 Ibid., 526.

55 Stewart, “Foods in Relation to Health,” 372.

56 Llamas, “Housekeeping and Cooking in the Leyte High School,” 614.

57 FlorenciaBonifacio. “School Lunches.” Philippine Craftsman 4, no. 4 (October 1915): 212.

58 Ibid.

59 Ibid., 211-212.

60 Munoz, “The Guihulngan School Lunch,” 50.

61 Ibid., 49-50.

62 Ibid., 50.

63 Bonifacio, “School Lunches,” 211.

64 Llamas, “Housekeeping and Cooking in the Leyte High School,” 613-614.

65 Kramer, Paul A. The Blood of Government : Race, Empire, the United States, & the Philippines. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006; Kramer, Paul A. “Race-Making and Colonial Violence in the U.S. Empire: The Philippine-American War as Race War.” Diplomatic History 30, no. 2 (2006): 169–210; Marotta, Gary. “The Academic Mind and the Rise of U.S. Imperialism.” American Journal of Economics & Sociology 42, no. 2 (April 1983): 217–34.

66 Edna A. Gerken. “Health in Our Educational Program.” Philippine Public Schools, July 1930, 150.

67 Llamas, “Housekeeping and Cooking in the Leyte High School,” 611.

68 Kilmer O. Mos. “The Central Luzon Agricultural School.” Philippine Craftsman 2, no. 8 (February 1914): 581.

69 W.J. Cushman. “The Villar Settlement Farm School.” Philippine Craftsman 2, no. 8 (February 1914): 558-559.

70 Ibid., 558.

71 Hurst, “Domestic Science in Misamis Provincial High School,” 40.

72 Ibid.

73 Alice M. Fuller. “Domestic Science as Taught in the Cagayan Provincial High School.” Philippine Education 4, no. 4 (September 1907): 46–48.

74 Ibid.

75 Fuller, “A Course in Domestic Science.” Philippine Education 5, no. 6 (November 1908): 29.

76 Fuller, “Cooking-Sewing.” Philippine Education 5, no. 10 (March 1909): 34.

77 Miller, “Results from Domestic Science,” 458.

78 Ibid.

79 Llamas, “Housekeeping and Cooking in the Leyte High School,” 612-613.

80 Dworak, “The Cotabato Moro Girls Industrial School,” 685-686.

81 Ibid.

82 “Mellin’s.” Philippine Education 4, no. 4 (September 1907): 3.

83 Ibid.

84 “Armour’s Meat.” Philippine Education IV, no. 3 (August 1907): 12.

85 “The Imperial.” Philippine Education IV, no. II (July 1907): 9.

86 Kristin L. Hoganson. Consumers’ Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865-1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

87 Miller, “Results from Domestic Science,” 451.

88 Ibid., 450-451.

89 Ibid., 451.

90 Munoz, 49–50.

91 Ibid., 50.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

“Armour’s Meat.” Philippine Education IV, no. 3 (August 1907): 12.

Bonifacio, Florencia. “School Lunches.” Philippine Craftsman 4, no. 4 (October 1915): 212.

Breckner, Silva M. “Our Domestic Science Work and Some of Its Results.” Philippine Craftsman 3, no. 5 (November 1914): 338.

Cushman, W.J. “The Villar Settlement Farm School.” Philippine Craftsman 2, no. 8 (February 1914): 558-559.

Dworak, Anna Pinch. “The Cotabato Moro Girls Industrial School.” Philippine Craftsman 3, no. 9 (March 1915): 685-686.

Fuller, Alice M. “A Course in Domestic Science.” Philippine Education 5, no. 6 (November 1908): 29.

___________. “Cooking-Sewing.” Philippine Education 5, no. 10 (March 1909): 34.

___________. “Domestic Science as Taught in the Cagayan Provincial High School.” Philippine Education 4, no. 4 (September 1907): 46–48.

Gerken, Edna A. “Health in Our Educational Program.” Philippine Public Schools, July 1930, 150.

Hurst, Carrie L. “Domestic Science in Misamis Provincial High School.” Philippine Education 4, no. 6 (November 1907): 40.

Kindley, George. “The Lumbayo Settlement Farm School.” Philippine Craftsman 2, no. 8 (February 1914): 564.

Llamas, Genoveva. “Housekeeping and Cooking in the Leyte High School.” Philippine Craftsman 4, no. 8 (February 1916): 609.

___________. “How the Teaching of Domestic Science Is Influencing the Home.” Philippine Craftsman 4, no. 8 (February 1916): 525.

“Mellin’s.” Philippine Education 4, no. 4 (September 1907): 3.

Mendoza-Guazon, Maria Paz. The Development and Progress of the Filipino Women. Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1928: 32.

Miller, Hugo Herman. “Results from Domestic Science.” Philippine Craftsman 2, no. 7 (January 1914): 444.

Mos, Kilmer O. “The Central Luzon Agricultural School.” Philippine Craftsman 2, no. 8 (February 1914): 581.

Munoz, Jose C. “The Guihulngan School Lunch.” Philippine Public Schools, February 1930, 49–50.

“New Plans for Home-Economics Buildings.” Philippine Public Schools, November 1931, 397.

“Photographs for Publication Showing Home-Economincs Activities.” Philippine Public Schools, February 1928, 28.

“Present Trends in Home Economics Instruction.” Philippine Public Schools, October 1928, 295.

Salud, Eusebio B. “A Milk-Feeding Experiment.” Philippine Public Schools, March 1930, 89.

“The Imperial.” Philippine Education IV, no. II (July 1907): 9.

Secondary Sources

Alzona, Encarnación. A History of Education in the Philippines, 1565-1930. Manila: University of the Philippines Press, 1932.

Anderson, Warwick. Colonial Pathologies : American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

Camacho, Marya Svetlana T. “Woman’s Worth: The Concept of Virtue in the Education of Women in Spanish Colonial Philippines.”Philippine Studies55, no. 1 (2007): 53.

Camagay, Maria Luisa T. Working Women of Manila in the 19th Century. Manila: University of the Philippines Press and the University Center for Women Studies, 1995.

Claudio, Lisandro E. “Beyond Colonial Miseducation: Internationalism and Deweyan Pedagogy in the American-Era Philippines.” Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 63, no. 2 (2015): 193–220.

Clymer, Kenton J. “Humanitarian Imperialism: David Prescott Barrows and the White Man’s Burden in the Philippines.”Pacific Historical Review45, no. 4 (1976): 495–517.

Doeppers, Daniel F. Feeding Manila in Peace and War, 1850-1945, New Perspectives in Southeast Asian Studies. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2016.

Franklin, V. P. “Pan-African Connections, Transnational Education, Collective Cultural Capital, and Opportunities Industrialization Centers International.”The Journal of African-American History96, no. 1 (2011): 44–61.

Goh, Daniel P. “States of Ethnography: Colonialism, Resistance, and Cultural Transcription in Malaya and the Philippines, 1890s-1930s.”Comparative Studies in Society and History49, no. 1 (2007): 109–142.

Hawkins, Michael. “Imperial Historicism and American Military Rule in the Philippines’ Muslim South.”Journal of Southeast Asian Studies39, no. 3 (2008): 411–429.

Hayden, Dolores. The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1981.

Hoganson, Kristin L.Consumers’ Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865-1920.Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Hollnsteiner, Mary Racelis, and Judy Celine A. Ick. Bearers of Benevolence: The Thomasites and Public Education in the Philippines. Pasig City, Philippines: Anvil Pub, 2001.

Kramer, Paul A. “Race-Making and Colonial Violence in the U.S. Empire: The Philippine-American War as Race War.”Diplomatic History 30, no. 2 (2006): 169–210.

.The Blood of Government : Race, Empire, the United States, & the Philippines. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Leavitt, Sarah. From Catharine Beecher to Martha Stewart: A Cultural History of Domestic Advice. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Marotta, Gary. “The Academic Mind and the Rise of U.S. Imperialism.”American Journal of Economics & Sociology42, no. 2 (April 1983): 217–34.

Matthews, Glenna. “Just a Housewife”: The Rise and Fall of Domesticity in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

McMahon, Jennifer M. Dead Stars: American and Philippine Literary Perspectives on the American Colonization of the Philippines. Diliman, Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2011.

Palmer, Phyllis M. Domesticity and Dirt: Housewives and Domestic Servants in the United States, 1920-1945, Women in the Political Economy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989.

Paulet, Anne. “To Change the World: The Use of American Indian Education in the Philippines,” History of Education Quarterly 47, no. 2 (2007): 173–202.

Rafael, Vicente L. “Colonial Domesticity: White Women and the United States Rule in the Philippines.”American Literature67, no. 4 (December 1995): 639–66.

Raftery, Judith. “Textbook Wars: Governor-General James Francis Smith and the Protestant-Catholic Conflict in Public Education in the Philippines, 1904-1907.”History of Education Quarterly38, no. 2 (1998): 143–64.

Reyes, Raquel A. G. Love, Passion and Patriotism : Sexuality and the Philippine Propaganda Movement, 1882-1892, Critical Dialogues in Southeast Asian Studies. Singapore: NUS Press ; Seattle, 2008.

Reyes, Raquel A. G. “Modernizing the Manileña: Technologies of Conspicuous Consumption for the Well-to-Do Woman, circa 1880s–1930s.”Modern Asian Studies 46, no. 1 (January 2012): 193–220.

Sta. María, Felice.The Governor-General’s Kitchen: Philippine Culinary Vignettes and Period Recipes, 1521-1935. Pasig City, Philippines: Anvil, 2006.

Sianturi, Dinah Roma. “‘Pedagogic Invasion’: The Thomasites in Occupied Philippines.” Kritika Kultura 0, no. 12 (2009): 26.

Steinbock-Pratt, Sarah. “‘We Were All Robinson Crusoes’: American Women Teachers in the Philippines.” Women’s Studies 41, no. 4 (2012): 372–392.

Torres, Cristina Evangelista. The Americanization of Manila, 1898-1921. Diliman, Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2010.

Ventura, Theresa. “Medicalizing Gutom: Hunger, Diet, and Beriberi during the American Period,” Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 63, no. 1 (2015): 39–69.

Villareal, Corazon D., Thelma E. Arambulo, Guillermo M. Pesigan, and American Studies Association Of The Philippines. International Conference And Annual Assembly. Back to the Future: Perspectives on the Thomasite Legacy to Philippine Education : Papers Presented at the International Conference and Annual Assembly of the American Studies Association of the Philippines, Ateneo de Manila University, Loyola Heights, Quezon City, August 24-25, 2001 / Corazon D. Villareal, Editor ; Thelma E. Arambulo, Guillermo M. Pesigan, Associate Editors. Manila, American Studies Association of the Philippines in cooperation with the Cultural Affairs Office, US Embassy, 2003.

Wesling, Meg. Empire’s Proxy American Literature and U.S. Imperialism in the Philippines. New York: New York University Press, 2011.

René Alexander Orquiza, Jr. is an assistant professor of history at Providence College. He focuses on twentieth century United States social and cultural history, the Philippine-American relationship, and immigration history. His manuscript, A Pacific Palate, is in progress. It focuses on the American efforts to transform the diet, cooking, restaurants, and commodity consumption in the Philippines during the American Period. He completed his doctorate in history at The Johns Hopkins University and is a recipient of fellowships from Mellon Foundation, the Huntington Library, and the Fulbright Institute of International Education.