From Sanitation to Soybeans: Kitchen Hygiene and Nutritional Nationalism in Republican China, 1911—1945

References | Author Bio | ![]() Download the PDF

Download the PDF

Keywords: China, hygiene, nutrition, public health, 20th century

The city of Fuzhou in June 1920 was the site of an epic battle between Mr. Cholera and Mr. Health. The former, a sickly-looking eight-foot-tall bamboo puppet that had a permanent following of “flies and odors” cackled as he was pushed through the streets on a float. Mr. Health, a plumper figure with rosy cheeks, swooped in to save the people of the city. As he fought, he communicated remedies and hygiene advice, voiced by students with megaphones.1 The event was an anti-cholera parade, held as a collaboration between the YMCA, its affiliated Council on Health Education, the Fuzhou municipal government, and corporate donors. News reports after the event recorded that more than 330,000 people came to see the parade.2

This article focuses on the “kitchen” as a space—both literal and symbolic—that underwent hygienic reform in Republican China. The kitchen referred to not only spaces in which food was stored and prepared, but also served, eaten, and shared. “Kitchen hygiene” education began as innovative methods to facilitate cholera prevention in Chinese cities such as Fuzhou through the reform of food preparation and kitchen sanitation habits. Based on a globally-circulating, scientifically-, politically-, and popularly-defined ideal vision of the hygienic kitchen, provincial, municipal, and individual entities mediated their interpretations and realizations of these clean spaces. Their efforts emphasized the ease and practicality with which individual households could keep their cooking and dining spaces free of microbes and disease vectors. With these efforts came a proliferation of cleaning guides, recipes, and advertisements that championed clean and whole foods and cooking methods that maintained the natural “food value” integrity of ingredients.3 Over the next decades, concurrent with a global clean-eating movement, nutritional science advancements, popularization of New Life Movement (1934 onwards) virtues, and the start of the Sino-Japanese War (1937—1945), hygiene reformists in China then turned their attention towards the prevention of tuberculosis and beriberi. As full-blown war with Japan began, Chinese authorities needed to quickly vaccinate and disinfect water sources to prevent cholera yet again, and public campaigns for kitchen hygiene saw a resurgence. However, this time, such efforts were accompanied by nutrition advocacy, the content of which had become particularly Chinese and patriotic. In the ideal Chinese kitchen, nutrition thus became the corporeal counterpart of what began as an environmental hygiene movement, and the pursuit of kitchen and dietary hygiene a way in which every individual could easily and patriotically participate in scientific progress.

The conceptual framework of kitchen hygiene, much like the term “hygiene” itself, underwent a transformation that made it increasingly more encompassing, more “scientific,” and instructive for both private life and expectations for modern citizenry. As Ruth Rogaski has examined, weisheng 衛生 encompassed much more than just “hygiene,” but rather “hygienic modernity.”4 Reformists certainly intended for kitchen and dietary hygiene reforms to foster a sense of personal responsibility, but the reforms’ contributions to public health were perhaps more diffuse than those to the development of meanings of the “self” and its place within a strong, modern nation. The modernity of a public health system, writes Tom Crook, “resides in its complexity,” “a shifting assemblage of interacting parts and practices” of those doing the would-be modernizing reforms and the initiatives themselves.5 Kitchen hygiene reformists included, but were more diverse than, Rogaski’s Tianjin elites—they were also medical missionaries, publishers of hygiene journals, advertisers, teachers, students, and women. The scope of their reforms was also not unique; for example, kitchen hygiene mirrored the development of “domestic management” as a life science and academic endeavor for women, as Helen Schneider has examined. Chinese women intellectuals who designed and promoted home economics programs were aware of similar global trends and set out to “find practical solutions to help Chinese women meet the responsibilities of domestic management” not only at home; their new skills had wider implications in society—women who studied “cafeteria management and nutrition … [would be prepared for] work in hospitals, in school dining rooms, or in restaurants as managers.”6 Later, with the establishment of the New Life Movement women’s organizations in the 1930s and 1940s, kitchen hygiene and domestic management initiatives often coalesced into defining the “markers of a civilized society” and the ways in which individuals could align themselves with wartime production.7

Cholera Prevention Before the Kitchen

Of all infectious diseases that could reach epidemic proportions, the one most closely associated with the kitchen was cholera. The idea that cholera prevention could be linked to food preparation or eating habits had staying power even after the discovery of the waterborne cholera bacillus and the development of a prophylactic vaccine by the late nineteenth century. European colonial governance and “Christian activism” in Asia and Africa linked cholera susceptibility to natives’ “culture”—the lack of “cleanliness, airiness, [and] good food.”8 Medical professionals in China at the turn of the century certainly blamed transmission on the “dirty individual.” Hamstrung by the costs of building new infrastructure and alarmed by the lack of progress with native populations, colonials and missionaries turned to protecting themselves. “What could be done, like the boiling of water, had to be done by the people themselves.”9 Reports about a cholera outbreak in 1926 Shanghai highlighted the stark contrast between the “few foreigners” affected in the French Concession and International Settlement and the several thousand cases, with hundreds of deaths, in the Chinese section—“dependent upon the Chinese-owned and controlled water works company.”10 Even if the Chinese were not biologically weaker in the face of cholera, it seemed that their living habits were certainly putting them at risk. Foreign residents could, and did, protect themselves in their own enclaves by maintaining their own hygienic kitchen and bathroom spaces and avoiding Chinese food at social events, on ships sailing down the Yangtze River, and even in hospital wards.11

Authorities around China before the 1920s had chosen to tackle cholera outbreaks in several different ways, including constructing seasonal hospitals and small-scale water sanitation projects. Cholera was familiar to Chinese society, but its prevention was sparse, ad hoc, and hardly institutionalized. It was in this context that reformists, along with local governments, promoted the kitchen as a desirable hygienic space and taught the individual to exercise agency. By all measures, the 1920 parade seemed to make an impact. Follow-up investigations showed that “even in the homes on small streets there is a decided difference in the cleanliness of all food used,” and “one seldom sees water-soaked fruits being sold on the street.”12 “[M]elon and meal dealers” all around Fuzhou began to use screens to keep out flies from their shopfronts and cover their merchandise.13 Similar initiatives also drew positive feedback. In Ningbo, the doctor in charge of treatment for more than 9,000 cholera patients was presented with a “silver-plated shield with complimentary characters on it” by the local elite as a gesture of gratitude.14

A few years later, William Wesley Peter, the Shanghai-based head of the Council for Health Education and director of the Fuzhou parade repertoire, published an overview of the campaign. With a focus on “broadcasting health” rather than “curing” (as in a clinical setting) or “controlling” (as with strict quarantines) disease, Peter signaled a new way for medical personnel to disseminate information to a larger audience and “enable” them to make progress. The Fuzhou parade was indeed a spectacle, but its innovative intention was actually to target smaller, more private aspects of everyday life. Each float in the parade used common household objects to demonstrate what an ordinary family could do to keep their food safe, accompanied by voiceover explanations in easy-to-memorize slogans. 300,000 pieces of “illustrated cholera literature” were distributed so that participants could bring written reminders—“boil your water and cook your food. Eat it hot from clean dishes … ”—back to their homes.15 The Fuzhou municipality sourced and paid for vaccinations, but the focus was on assigning personal responsibility for the hygiene of each individual kitchen, restaurant, food stand, market stall, and dining area.16

The shift by hygiene reformists to focus on personal responsibility in food preparation and consumption could thus be interpreted as the next step of a racialized, colonial, civilizing mission, especially as it was led by missionary boards and the YMCA. Alternatively, it was a stopgap for the failure of Chinese and treaty port authorities to safely upgrade hygiene infrastructure or enforce sanitary laws. As Chieko Nakajima writes, Shanghai elites launched mass educational hygiene campaigns to mitigate the damage of city administrators’ inability to build new infrastructure.17 But commercial- and print-driven interest in hygiene and individual education actually grew in tandem with, and not in spite of, state-run initiatives: laboratory research for cholera prevention and therapies, the establishment of infectious disease hospitals, and the increased manufacturing and distribution of vaccines. As Chinese citizens’ expectations for government services increased, so did their own consciousness about personal hygiene and responsibility.

"The Tiger is Coming"

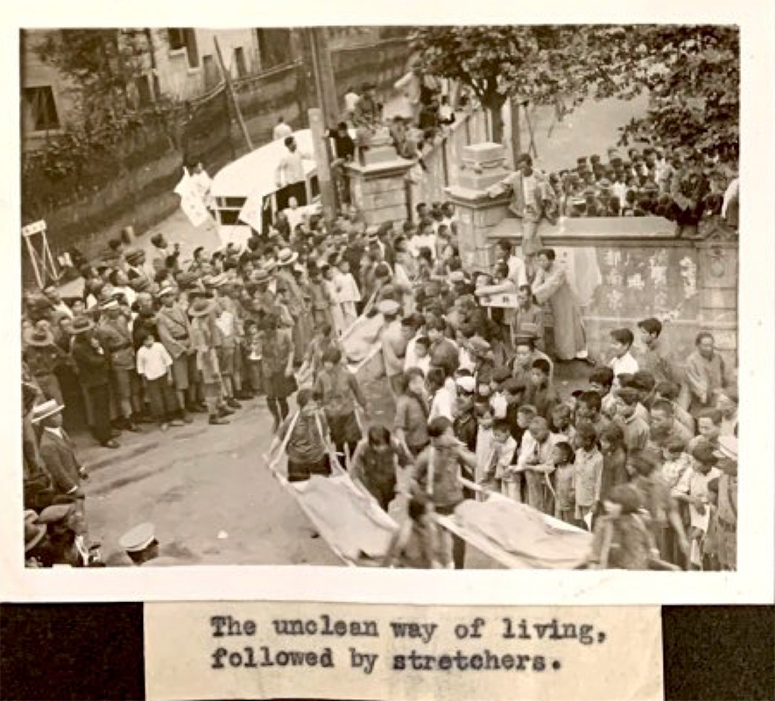

Following the Fuzhou success, large-scale cholera prevention campaigns continued in Chinese cities. Shanghai’s International Settlement, French Concession, and the Chinese municipality collaborated on a 1931 parade. They used sensationalist methods—dozens of stretchers with “dead bodies” with giant models of flies swarming around them carried through the streets—to indicate what would happen when the health advice was not taken.18 The parade was an admonishment of Shanghai residents’ dereliction in their hygienic duties and a demonstration of how everyone could and should take personal responsibility, using simple methods, in their own homes. Having observed the models of the “right” and “wrong” way, the public was now also expected to point out and correct bad behavior. Overall, an estimated 625,000 people were in attendance, and this became one of the largest hygiene education public events to date. On a smaller scale, Jiangxi’s 1935 summer cholera campaign, an initiative of a local New Life Corps or Schools Hygiene Team (xuexiao weisheng dui 學校衛生隊) during the New Life Movement’s popularization, featured radio broadcasts, theatrical performances, and a citizen cleaning initiative.19

Written promotional materials instructed that people could not allow social niceties or carelessness to prevent them from following proper hygiene advice when the “scary summer [comes] back” with cholera in tow.20 The Council on Health Education’s companion pamphlets for their travelling lectures tackle the “agents” of cholera—flies, raw water, sick people, and uncovered food—in a series titled “Health-Picture Talks,” (weisheng tushuo 衛生圖說). Illustrated panels are accompanied by narrative descriptions and catchy rhyming couplets to help readers remember the advice. A picture of several men socializing in a tea house is captioned: “on the surface everything looks orderly, but think about this teacup, this smoking pipe: how many people will drink from it? How many people will smoke from it? One cannot be sure that every person is healthy.”21 A first-hand account by a Shanghai resident, written after a visit to a literature professor friend’s house, described alarm at the stubbornness of Shanghai’s elite to disregard public health advice and insist on keeping their bathrooms close to their kitchens “for visitors’ convenience.”22 Hangzhou’s residents were also asked to refrain from visiting the sick or mourning the deceased in homes that were likely contaminated.23

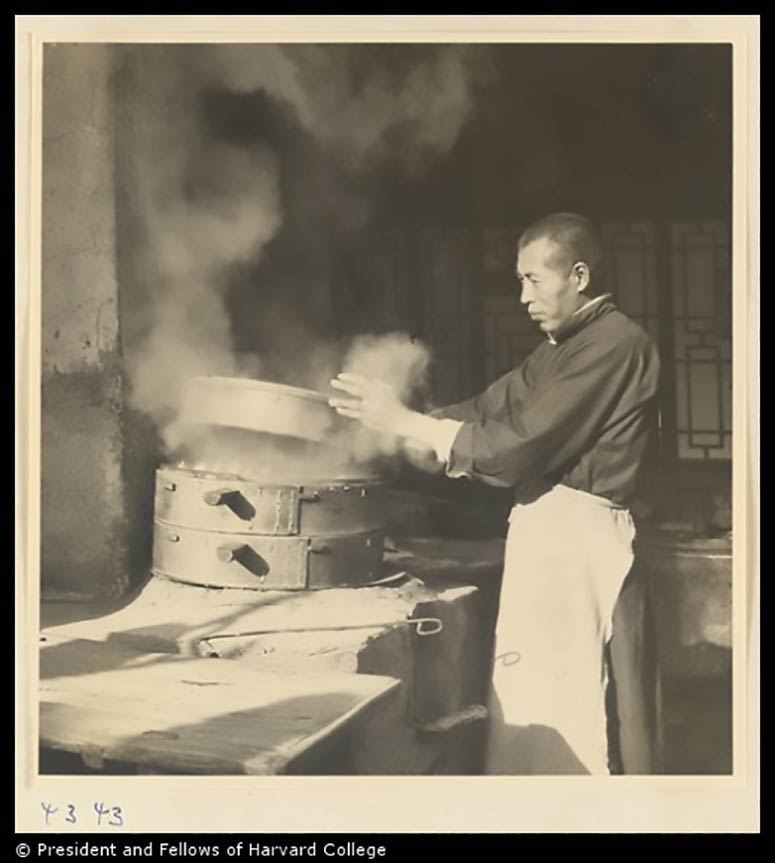

For restaurants and other food services, the Ministry of the Interior released a series of cleanliness guidelines in 1928 in its government bulletin. Chefs were expected to cut their hair and nails regularly, wash hands after using the bathroom or scratching their noses, and refrain from “coughing or yelling towards pots and bowls while cooking or carrying food.”24 The kitchens themselves also needed to conform to using screens and traps for flies and rodents and a daily floor cleaning. The water used to boil rice and vegetables should be sold for pig feed, not be dumped onto the ground.25 The National Health Administration’s public road health stations (weisheng gonglu zhan 衛生公路站) developed a set of investigation forms for grading the environmental hygiene of restaurants, public wells, and other facilities in each jurisdiction.26 A restaurant in Shantou that failed to provide fly traps, white-colored uniforms for all staff, or spittoons for customers, among other requirements, would be fined up to ten yuan for each offence.27 From 1930, any restaurant in Nanjing could be subject to a hygiene inspection at any time.28

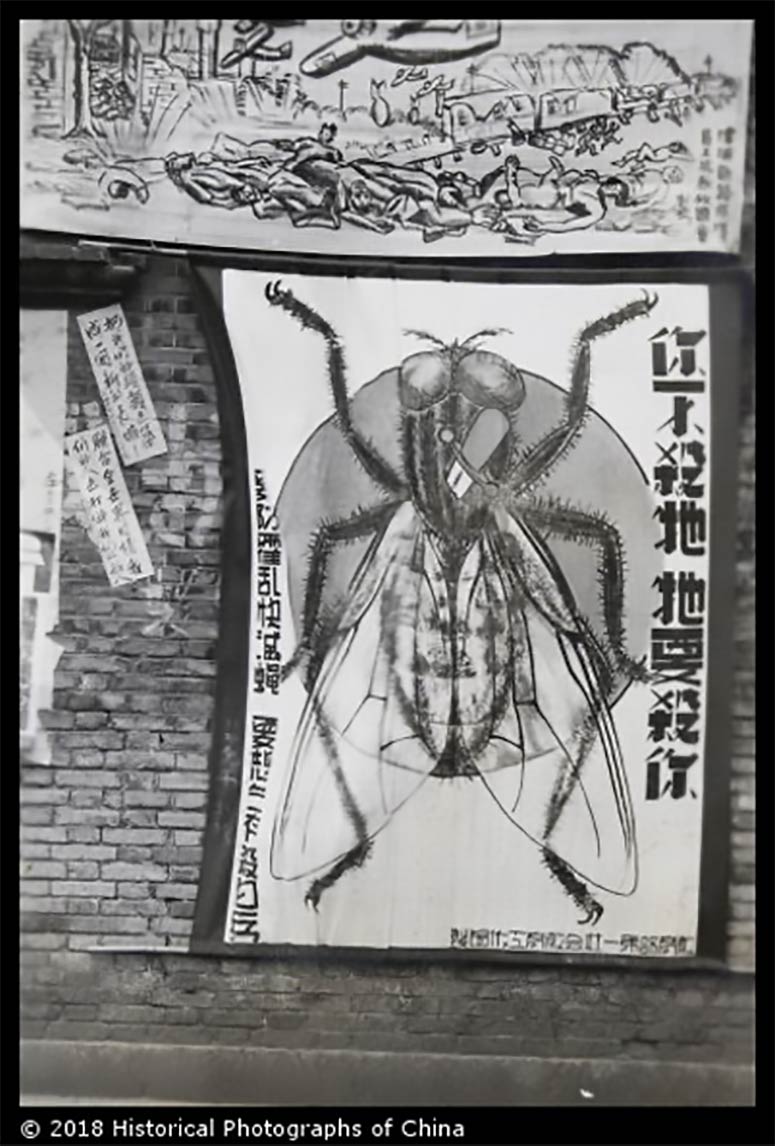

Often, descriptions of cholera recalled the frightening puppets that were the stars of the Fuzhou parade. A pamphlet from the Hangzhou government warned “esteemed readers” that “cholera will soon become another uninvited guest to the Hangzhou area, and just thinking about last year’s situation is so painful.”29 Cholera was an “invader,” and could sneakily lead one to “sink into a trap” if not careful.30 The apt phonetic transliteration of the word “cholera” as “tiger plague” or “tiger fierce pull” (hu yi 虎疫, or hu lie la 虎烈拉), referred to its speed and violence that executed its victims within a few hours; it also perfectly aligned with its more popular, traditionally-derived name, “sudden turmoil” (huoluan 霍亂).31 In a graphic description of the suffering of a cholera victim, the “tiger plague” was personified as “an enemy of the people.”32 Its special agent, the common fly, was an intentional agent of destruction, and a “murderer”: “green-bellied, red-headed, often clothed in filth; contaminated with bacteria from food, transmitting sickness as fast as the wind blows.”33 In a poster produced by the Council on Health Education, a child eats his dinner while a fly of equal size feeds from the other side of the bowl.34 According to a Rockefeller Foundation report, “there is reason to believe that gastro-intestinal diseases in China cause at least 5 deaths per 1,000 population per year and that most of this is fly-borne."35

Fortunately, prevention against this malicious disease and its vectors was achievable. “To sanitize our cooking utensils,” wrote Shi Cui in an editorial, “we simply need to boil them.”36 Primary school students’ efforts to sanitize drinking water in Xinhe, Jiangsu, were documented in a series of lantern slides that showed easy, step-by-step instructions in images and accompanied narrations.37 A Hangzhou resident who received a “The Tiger is Coming” pamphlet could provide a necessary public service by simply reading, memorizing, and “showing [this] to others, or reading it to them if they are illiterate.”38 Participating in a fly elimination campaign was arguably the best way for an individual to prevent cholera, “maintain public morality[,] and serve the society.”39 Fly and mosquito control had in fact been a significant undertaking for many Chinese city governments. Beginning in 1922, the Nanjing government detailed 5,000 dollars and two dozen policemen to the health bureau for fly larvae elimination in public water sources and latrines every summer.40 The city of Hangzhou called on its residents to “do their duty” and “actively reduce flies: use swatters, water traps, and covers to prevent flies from getting near food.”41 After killing flies, one should “simply throw bodies into the fire or drown them to eliminate the germs.”42 Armed with fly swatters and clenched fists, the students and faculty of a school in Shandong posed for a photo with the caption, “Notice is hereby given that any fly who appears … does so at his own risk … by order of the FLY ELIMINATION CAMPAIGN.”43

Contemporary commentators marveled at the impact of intentional fly-killing. The Rockefeller Foundation reported that the kitchen fly traps made by a Mr. Yang at South-Eastern University were so effective that “there were practically no flies” during a particularly hot summer.44 The Beijing Municipal Department of Public Safety hosted an anti-fly campaign in 1930, in which participants were awarded a copper coin for every ten flies caught—“a total of 12,134,010 flies were caught in the city during the summer at a cost of $2,018.68.”45 Each student at a Chongqing middle school was reportedly able to catch and kill at least twenty flies each evening.46 Guangzhou’s public bulletin declared its fly elimination work a success, claiming that “the waves from last year’s fly elimination work have gradually spread everywhere, to villages and to the old and young.”47

The story of Qiaotou Elementary School, just outside of Shanghai, was even written into an issue of the popular Commercial Press book series for primary school readers, titled “Campaign to Eliminate Mosquitos and Flies” (quchu wencang yundong 驅除蚊蒼運動). The student government organization decided to start a fly killing campaign to help local residents feel safe from disease. The student-led team instructed their peers and elders to use simple fly swatters and traps to kill the flies, which could then be used to feed poultry to keep them plump.48 The report of this fly elimination campaign showed that an entire community was apparently enlightened and emboldened through the experience. By the end of the campaign, no villager could deny that flies were dangerous enemies.49 In all these cases, the successes were said to be due to the work of “one or two teams that led the charge and many others followed.” Just as a single student could start a campaign that would change the minds of hundreds in Qiaotou, every Chinese person could start from killing a few flies to make progress.

From Clean Kitchens, to Clean Food, to Clean Eating

Advice for what the common Chinese person should do with his or her kitchen soon extended beyond mere cleaning. With the mass publication of special interest magazines for public consumption, advertisements, news of health-related progress, cleaning advice, and recipes all found a home. Journals such as Shanghai’s Weisheng yue kan (Health monthly magazine 衛生月刊) published both medical progress news and advice for the general reader, while other publications ran regular columns for recipes and “hygiene common knowledge.” Recipe guides until the mid-1930s were educational eye-openers for those who were able and willing to broaden their dietary interests and make creative, cosmopolitan changes to their routines. They were perhaps aspirational to many but went hand-in-hand with the proliferation of advertisements for food and nutritional products in the print media.

To understand the transition of the kitchen from a place that simply needed to be free of germs and flies to one that could positively foster wonderful health benefits, we must necessarily discuss nutritional hygiene and food science at the global level in the early twentieth century. In The Pasteurization of France, Bruno Latour describes the teachings of French “hygienists” in the Revue Scientifique journals in the 1880s as an “accumulation”: “advice, precautions, recipes, opinions, statistics, remedies …” in attempts to launch “all-round combat” on diseases.50 Unlike research bacteriologists, who may have considered disease to be caused only by specific microbes, the hygienists considered any and all factors as possible causes. China’s authors for cleaning, cooking, and recipe advice followed a similar all-encompassing framework, and moreover, showed that the hygienist mode of understanding health—the absence of not only disease but also other undesirable elements—held firm even well into the twentieth century, after the medical community’s acceptance of germ theory and the popularization of targeted therapies.

Eliminating microbes to reach a hygienic ideal also required setting up entire ecosystems that contributed to a more general abundance of healthfulness. It was thus not sufficient, according to kitchen cleanliness guides, to merely clean and sanitize cooking equipment, but the entire kitchen needed to be shielded from even dust.51 The “whole suspect outer world” needed to be controlled not only for ultimate elimination of microbes, but also for more “transcendental” goals —“asepsis,” or “complete isolation” from any pollution.52 The term “dietary hygiene” (yinshi weisheng 飲食衛生) emerged to encompass cleanliness guidelines for kitchens, cooks, diners, dining rooms, the food itself, and the surroundings in which it was served. Meals also needed to achieve aesthetic standards. Health’s “table for housewives to clip out and post in the kitchen” was a short guide for teaching cooks at home to “save food value as well as appearance of flavor,” indicating that appealing-looking vegetables were more likely to be eaten.53 “Regardless of whether one uses gold, china, or bamboo [to serve], all equipment should be clean and neat.” Food should be arranged beautifully, and at the correct proportions between serving vessel and amount of food.54

Readers were also encouraged to broaden their horizons and improve the variety of their diets. After explaining necessary nutritional content—iron, protein, carbohydrates, etc.—for health and in which foods to find them, an article in Weisheng yue kan ends with a “motto for three daily meals”: “Every day I will eat: one pound of milk, one egg, one item of fish or soybeans, one item of potatoes, large amount of vegetables, unhusked wheat bread or coarse grains, and one item of fruit.”55 A “Home Hygienic Cooking Guide” (Jiachang weisheng pengtiao zhinan 家常衛生烹調指南) published in 1932 by the Commercial Press, part of the “Family Reference Book” (Jiating congshu 家庭叢書) series, deemed itself the quintessential guide for anyone unfamiliar with cooking, as well as a well-rounded guide to disinfecting cookware and safe food preparation techniques.56 While the recipes included are elaborate and often lengthy, including an entry for “roast goose,” both parts of the book—the hygiene guide and the recipe collection—were created specifically for the use of the individual at home. Moreover, the provision of appropriate and sanitary kitchen equipment would not only ameliorate a family’s health, but also protect and lessen the workload for the “housewife,” (zhufu 主婦) the undisputed manager of the kitchen.57 Exploring new recipes could also help bring families closer together: “this book should be interesting to many, especially women, but families can make use of the book to read together.”58

At the same time, a global movement towards clean eating and natural foods emerged. New Deal food writing in the 1930s, according to historian Camille Bégin, reacted to the rise of mass-produced industrial food and took moral stances around the “dichotomy between real and fake, good and bad food” that persist even to today.59 Frozen vegetables and refrigerated meat, considered more “pure” compared to processed or packaged foods, became available to those who could afford them. In the global natural food movement of the early twentieth century, Chinese food experts declared their distinct advantage. Overseas Chinese restauranteurs in the United States, to combat pervasive racialized discrimination of Chinese food as dirty, cheap, and lower class, drew upon the “traditional” wisdom of their ancestors in published cookbooks from as early as the fourteenth century. These were written with an “emphasis on food as a means to maintain the health of the individual” and also to strengthen his relationship with society.60 Traditional recipe books, such as the eighteenth century Record of Xing Garden with its collections of meals of “coarse foods, like vegetables and stews,” became models for writers in the early twentieth century.61 Chinese American restaurant owners and cookbook writers would often evoke the concept of “nourishing life” (yangsheng 養生) in their own publications around the turn of the twentieth century.62

American audiences took notice of Chinese ingredients such as soybeans and vegetables as nourishing additions to a frugal, Protestant diet.63 Chinese methods of cooking—such as using a steamer as to not overcook or damage the structural and nutritional integrity of vegetables—were particularly lauded, with one writer proudly announcing that the longtime staple Chinese steamer pot had only recently been introduced to Western countries. Furthermore, the Chinese tendency to eat a variety of animals’ internal organs, which are high in iron and other minerals, was also just beginning to gain popularity in the United States, validating the longstanding practice.64 Mark Swislocki writes that the increased interest in nutrition allowed Shanghaiers to connect with new values emerging in a cosmopolitan place and time but also to maintain their Chineseness at the same time. Reformists in China urged cooks to welcome natural, plant-, and animal-derived diets to receive the best nutritional benefits from their food. Aside from improving the health of Chinese people, this would also have a more grandiose effect—Chinese home cooks could thus have an important and leading role in the improvement of nutrition for people all over the world. After all, “Confucius,” wrote Shui Wong Chan in 1917, “taught [us] how to eat scientifically.”65

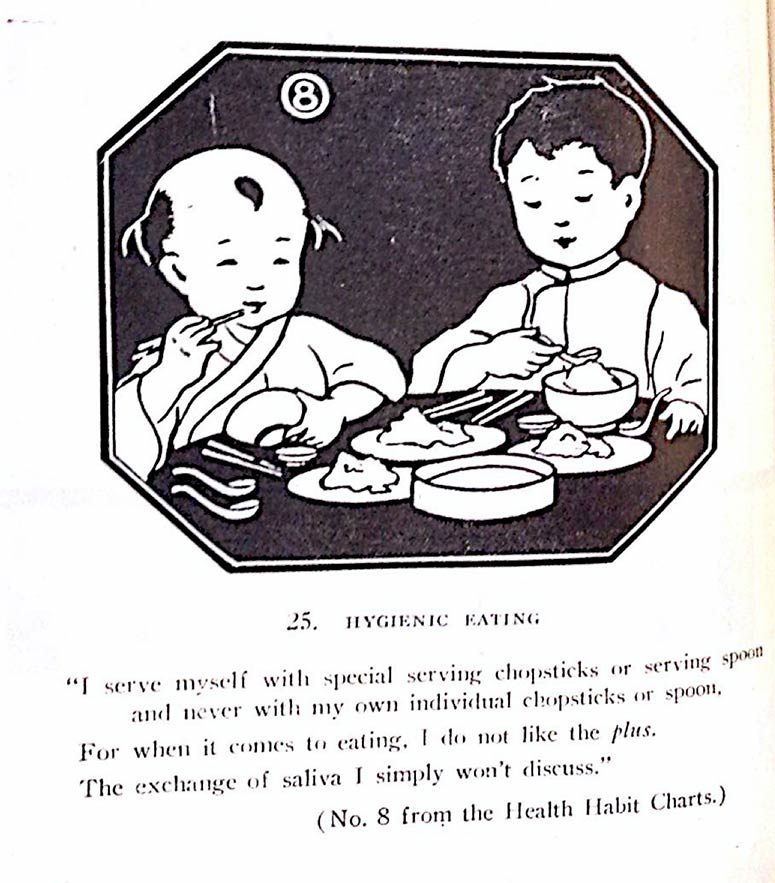

Once intricate, varied, natural, and carefully prepared food was served, diners would also need to follow certain guidelines while they were eating. The National Anti-Tuberculosis Association, established in 1933 by influential Chinese medical professionals, began to consider whether a particularly Chinese dining characteristic had caused the dizzying numbers of tuberculosis infections, even among wealthier, younger people—that of “communal eating” (gong shi 共食).66 The Association called for government support to ban this “communistic salivary exchange,” eating from a “common dish into which the diners indiscriminately plunge their chopsticks or spoons as they convey successive portions to their mouths.”67 Its leaders proposed several dining reforms: diners could serve themselves from shared dishes on a moving tabletop with designated serving utensils, carry two sets of utensils (one for eating, and the other “hygienic chopsticks” for serving) or eat only from individual servings that were portioned before each meal.68 It did not seem to concern members of the Association that tuberculosis was widely understood by this time to be an airborne disease for which people were infected through their lungs, nor that their contemporaries voiced doubts about whether communal eating was really so dangerous.69 Lu Liuhua, celebrated among the first generation of female Chinese doctors, expressed her reluctance to adopt “hygienic chopsticks.” Moreover, portioning out all food before the start of a meal would inconvenience those who were overly polite or late, and would actually undermine the beauty of Chinese cuisine, in which each dish was to be enjoyed separately!70

Nevertheless, the Anti-Tuberculosis Association was now sufficiently emboldened by central government developments such as the New Life Movement and support from important scientific and political figures to make these bold claims. Lu’s editorial, despite its ambivalence, concluded that China needed a temporary hygienic chopsticks solution to curb rising tuberculosis infection numbers, but it would not diminish the “strong social and family structures of Chinese culture.”71 Columnist Wang Zude presented case studies of Nankai and Tsinghua Universities, exemplary in both education and social norms, where students all carry two sets of utensils for serving and eating respectively.72 Even if not every family could afford to refashion their dining tables to spin, the range of proposed kitchen food and hygiene reforms were once again stressed as the most convenient, easy, and cost-effective ways to prevent the spread of tuberculosis. The inclusion of designated serving utensils in virtually every dietary hygiene guide throughout the 1930s was testament to their perceived potential. Chinese people could establish this simple, humane solution that would require neither infrastructure-building nor persecution.

Berberi, the New Life Movement, and the Patriotic Soybean

While specific events such as the Fuzhou and Shanghai cholera parades may have had missionary and colonial origins, and dietary hygiene was gaining its popularity globally as a new life science, the basic act of managing nutritional and hygiene habits in the kitchen to prevent disease had its Chinese roots. After all, the Chinese had their own longstanding dietary taboos—excessive drinking, gluttony, and the ultimate “processed food,” polished white rice. The idea that individual behavior as a main cause of disease had long existed in Chinese conceptions of wellness. The disease caused by thiamine (Vitamin B) deficiency known as beriberi, which caused swelling and numbness of the legs and feet, was one such example. It first made regular appearances as jiaoqi 腳氣 (foot qi) in Chinese physicians’ notes as a disease caused by the humid and hot climate of southern China. By the thirteenth century, physicians also considered the causes to be sufferer’s “habits, not their constitution or their environment” after examining some northern Chinese cases.73 These early epidemiologists bolstered their arguments with invocations of the political divisions between north and south China, reflected in people’s diets, wealth, and bodily strength. As Hilary Smith explains, the distinction between northern and southern versions of jiaoqi and the differentiation in their respective causes and cures began to fade as China became “newly unified.”74 By the early twentieth century, the integration of all existing understandings into one, scientifically-defined disease “beriberi” was similarly a product of both scientific progress and the political climate at the time: medical researchers were considering that microbes were not the only necessary causes of disease, vitamin synthesis was becoming common around the world, and China faced a looming threat from the rise of militaristic nationalism from Japan, for which beriberi posed a threat.75 Instead of vaccinations, antibiotics, and sanitation, the prevention and cure of the deficiency required dietary and habitual changes for all Chinese.

Fortunately, medical advice reassured general readers, the cure for both the disease and bad dietary habits could also easily be found domestically, and traditionally. Chinese doctors had identified its dietary correlations in the Tang Dynasty, eight centuries before European records.76 Even elite Japanese doctors had only recently accepted that beriberi was a diet-related disease in 1926, after decades of searching for a microbial cause.77 Its causes of dietary deficiency matched nicely with traditional Chinese medical concepts that designated behavioral attributes for certain ailments, and thus it is neither surprising that jiaoqi and beriberi coalesced into a common nutrition-related disease, nor that reformists agreed that the easiest cures were located in each individual’s kitchen. As Rogaski writes, Chinese medicine proponents by the 1930s had brought “an indigenous form of weisheng … into the ‘outer arena’ of race and nation” as wisdom that “resided within … Chinese people themselves.”78

Chinese wisdom dictated that preventing and curing beriberi required the individual to adopt humble, clean, and frugal practices in their dietary habits. Doctors in 1915 found that where rice was “grown, husked, and pounded locally” without steam milling and polishing, beriberi cases were nonexistent, even as towns a hundred miles away experienced epidemics.79 “Curing jiaoqi is not difficult,” wrote Jiang Tiyuan in 1935, “people who have the disease should not eat rice that is too white, and instead substitute with soy, wheat, or eggs, which are higher in Vitamin B.”80 As jiaoqi had been a disease associated with progress and decadent lifestyles, prevention methods were even more approachable. The cookbook Yinshi yu jiankang 飲食與健康 (Food and Health) blamed recent civilization for people’s inability to fight off germs and viruses— “cars and horses have decreased our exercise opportunities, and food has become more intricately processed which disrupts the nutrition we should have.”81 In fact, nutritional researchers found that urban Shanghai workers who preferred “polished rice” had worse nutrition than farmers and embodied how prosperity “corrupted traditional customs.” They argued that “it was time for the city to learn from the country.”82

Yinshi yu jiankang urged its readers to shift their goals away from achieving financial wealth and instead towards maintaining health. Communities around the country were lauded for efforts to eat and promote modest diets. At Yenching University, domestic management students’ experimentations with low-cost diets “heeded the demands of their discipline and their country as they … acted in practical ways to translate scientific ideas of nutrition to Chinese conditions.”83 An article on student nutrition criticized the dietary habits in wealthy southern towns (eating polished rice, “unthinkingly” filling up on rice porridge) for rendering jiaoqi affliction inevitable, and encouraged them to add coarse grains, soybeans, and eggs. The article even brought back the north-south divide over differences in dietary preference and nutrition, reiterating that beriberi’s causes had long been understood.84 The “ancient art” of Chinese nutrition offered the answers, even as the rest of the world had only recently begun to recognize the importance of vitamins.85

Furthermore, being prompted to recover from jiaoqi could, and should, also push the sufferer to make some additional lifestyle changes for better hygiene overall. If the individual could afford the expense, he or she should “relocate to recuperate” to a dwelling with dry air and good ventilation and sunlight.86 Similarly, to address the various different understandings of jiaoqi by readers who were perhaps perplexed about how exactly to combat the disease, answers in Weisheng yue kan’s regular column “Hygiene Q and A” (Weisheng wenda 衛生問答) reassured readers that regardless of what type of jiaoqi they had encountered or were trying to prevent (dry, wet, acute, malignant), their target diet should contain soy, vegetables, and lemons, their housing should be clean, sunny, and ventilated, and they should “avoid physical and psychological labor.”87 Should individuals in charge of public spaces such as schools or prisons find a jiaoqi patient, wrote Jiang, they should immediately improve the communal diet, and replace white rice with soy and wheat products to prevent further instances, while improving overall sanitation of the facilities.88 These written discussions about such a disease explained away common fears with attainable hygienic solutions and underscored the ease of behavioral change.

Thus, change for better jiaoqi prevention would come from within. This encouragement perfectly aligned with the launch of Chiang Kai-shek’s New Life Movement in 1934, for which Chinese citizens were expected to embrace ancient virtues of propriety and righteousness in every aspect of their lives.89 Above other tenets, the Movement’s teachings’ resonance with contemporary currents in Chinese society was loudest with the kitchen hygiene reformists. Chiang’s “Guidelines of the New Life Movement,” published in newspapers around the country in May 1934, advised readers that “eating utensils should be clean and food should be washed; one should eat local produce.”90 A series of cartoon panels in the New Life Movement Weekly magazine (Xinshenghuo zhou kan 新生活週刊) neatly summed up the teachings of kitchen hygiene to date: “do not drink raw water, do not eat unclean fruit in the summer, do not eat junk food.”91 Cleanliness, frugality, and rationality for kitchen hygiene were united under the banner of New Life with government endorsement.

Women were both the architects and targets of New Life kitchen hygiene efforts. As an extension of the New Life Movement’s socially-driven grassroots mobilization efforts, the New Life Movement Women Service Committee of Nanjing trained 4,500 women and girls from middle school students to government employees to become kitchen hygiene trainers at recruitment agencies for domestic staff.92 New Life women’s organizations’ work in kitchen hygiene improvement also capitalized on their foundational professional and disciplinary training in domestic management. Guidelines produced by the organizations from the late 1930s and early 1940s defined “cleanliness” as more than just washing one’s own body or cleaning public places, and more reminiscent of the Pasteurian hygienists’ all-round combat against impropriety. As kitchen hygiene experts, women could monitor the work of others. As domestic management educators, they could publish textbooks for general consumption. And, as housewives, women were expected to not only provide and prepare nourishing foods for their families, but also understand how to leverage the foods’ nutritional values to suit the needs of their family members’, and by extension, the needs of the nation.93

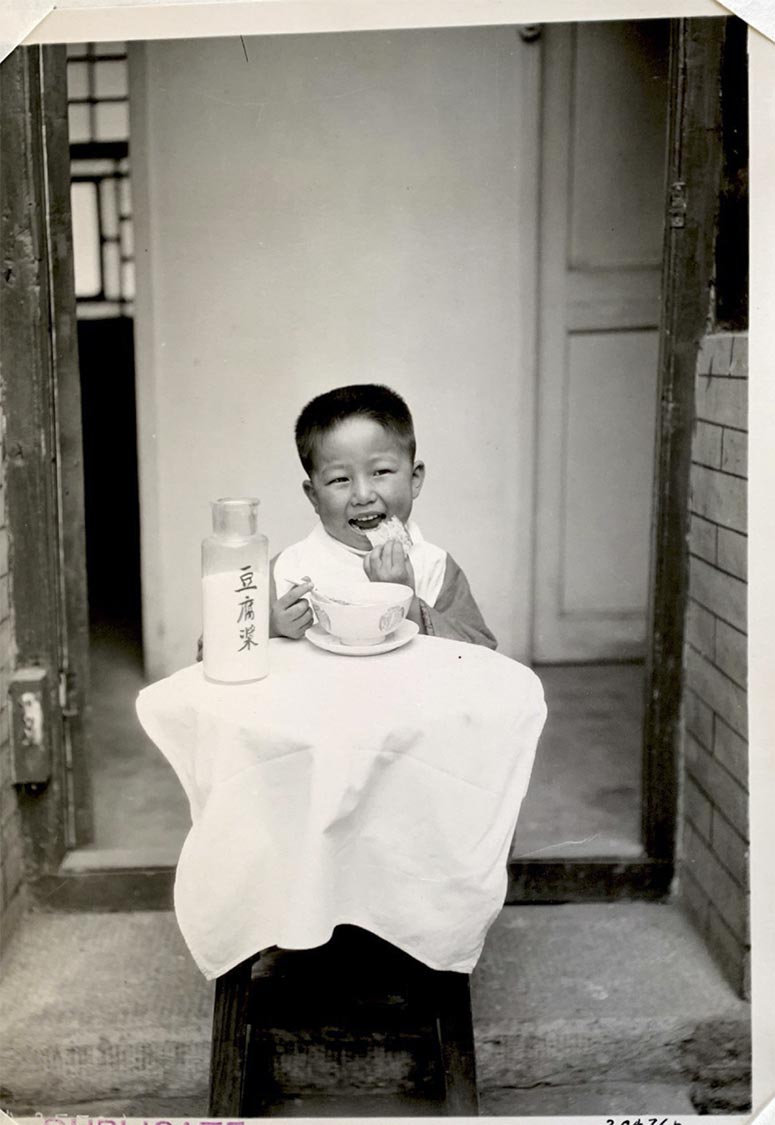

The perfect food that conformed to the ideals of the New Life Movement was the humble soybean. The soybean (and the economic potential of its industrialized production) had been a steadfast companion of China’s modernization, praised and even coveted by those in the West as a technologically-advanced innovation by the 1910s.94 Abundantly produced in China, the superfood was locally sourced and higher in calories, protein, and fats than the imported potato.95 Testing in the laboratories at the Peking Union Medical College throughout the 1910s and 1920s confirmed that soy milk could be exclusively used to feed infants, an excellent alternative to cows’ milk. Thus, the production of soybean milk and the improvement of nutrition for orphans and refugee children became something for which China could also take a global lead.96

While soy’s versatility and its links to Chinese innovation and pride were made clear, especially by the 1930s, it was the fact that soybeans were inexpensive that really made them popular to dietary hygiene reformists as a key food source. As early as 1905, Li Shizeng, a Chinese scientist and tofu entrepreneur in Paris, argued that soy milk would be the great class equalizer for nutrition. Poorer drinkers of soy milk would be able to receive all its nutritional benefits without having to pay the premium for cow’s milk, for which higher costs were attributed to sourcing and processing.97 The price of a quart of soy milk and two “bean dreg cakes,” enough nutrition for one day for an adult, “would cost about the equivalent of a 2 cent American postage stamp.”98 Soy milk, more uniformly produced in factories, was in fact more hygienic than cow’s milk, which needed to be carefully pasteurized.99 Chinese children had been drinking soy milk for thousands of years, one writer claimed, and as a result, rickets, rampant among foreign children, was hardly seen in China.100 Some newspaper editorials even suggested that it was a good alternative to breast milk.101 Foreign doctors in China, on furlough back home in the United States, hosted information sessions about the “complete protein food” that “sustains growth” to captive housewife audiences.102 An overseas Chinese man in Malaya who sold bean sprouts to his fellow compatriots attracted the attention of British authorities, and won acclaim for developing a product that was clean, affordable, and nutritious.103 Not only important to Chinese people within national borders, the soybean in fact began to connect Chinese around the world, and elevated the status of the entire race as creative and humane food technologists. Soybean products became intricately linked to Chinese innovation, scientific progress, and nationalistic welfare.

By the mid-1930s, kitchen hygiene reformists, nutrition advocates, soybean entrepreneurs, and the New Life Movement met at an intersection, symbiotically promoting the themes of frugality, cleanliness, devotion to the nation, and bodily strength. Initiatives from the 1920s gained national legitimization under the New Life Movement. In fact, according to contemporary writers, it was imperative that communal eating norms be dismantled in favor of splitting food into individual portions or enforcing the use of hygienic chopsticks. If not, picky Chinese diners would not get enough diverse nutritional hygiene and the nation would also generate more food waste, directly contradicting Chiang’s stated New Life directive that eating should be “to sustain life.”104 In other words, kitchen and food hygiene reforms over the past decades built the foundations on which the New Life Movement was even possible. Cholera, tuberculosis, and beriberi could all be defeated through the proscribed tangible and ideologically coherent methods.

Wartime Nutrition as the Tiger Returns

As the Japanese military occupied large areas along China’s east coast starting in 1937, massive inland migration led to crowding and difficulties in the supply chain for food. While China’s interior was able to begin producing a range of crops as the government and entire cities moved west and southwest, certain imported and coastally-produced foods became difficult to source.105 The government stepped in to curb grain price increases and to ensure that troops and government personnel were fed, but changes had to be made in the compositions of their diets.106 Cholera, typhoid, other gastrointestinal diseases, and nutritional deficiencies once again posed tremendous threats.

Large-scale vaccinations drives and sanitation efforts were established early on. After an outbreak of cholera in July 1939 killed around two hundred people near Hualong Bridge in Chongqing, the wartime capital city, epidemic prevention teams rushed to set up provisional cholera hospitals and emergency treatment stations in the area, and set disinfection squads to the river to make sure the drinking water was properly sanitized.107 Chongqing authorized a number of institutions to act as quarantine stations and enforcement agencies, and to issue certificates to people and vehicles once they were cleared. The staff—one doctor, one to three nurses, two to four assistants, and one support worker—were given vaccines, supplies, and diagnostic instructions to differentiate between infectious disease and food poisoning cases. Workers on ferries, cars, and public transportation were required to be checked for disease and instructed to examine their passengers and check for quarantine clearance certificates. Every water source used for public consumption was to have a sanitation team of one or two people who would add chlorine at least once a day and eliminate any fly larvae.108 In addition, authorities understood the necessity of vaccinating widely, and early. Fortunately, Chongqing’s cholera numbers during the war years were kept mostly low—in 1941, only seven cases were reported after the city vaccinated 150,000 people. By 1944 the Chongqing government could no longer meet all its vaccination targets because of wartime limitations, but the initial rapid efforts “averted disaster.”109

Preventive infrastructural efforts and vaccination drives had not been enough to curb cholera completely in the 1910s, and were definitely insufficient in the 1940s. Even the aforementioned government guidelines urged that to successfully and practically target both military and civilian populations, a concerted promotion effort must be made based on the “central themes” of food hygiene: “how to kill germs in food, simple ways to prevent flies, drink boiled water,” and others. Local governments were encouraged to launch “cholera prevention” and “hygiene campaign” weeks in collaboration with various local organizations, including medical bodies, New Life Movement chapters, and military organizations.110 The Eight Route Army, in the Communist Party’s base area in Shaanxi, set up its own army medical department which directed the digging of deep latrines and outfitting all kitchen windows with fly screens.111 Telegrams in Chiang Kai-shek’s own name were sent to military commanders around the country to remind “soldiers and officers to not drink or use raw water to prevent cholera.”112

The collaboration of a variety of agencies was especially important; in 1942, the Ministry of Social Affairs released an urgent memo regarding “society’s non-cooperation” with its business affairs administration, denouncing Kuomintang party members’ employment of gang-related criminal methods in the purchase and distribution of cholera vaccinations. Because of vaccine shortages (due to production, distribution, and corruption issues), it was thus even more important for groups and individuals to know about how to prevent cholera for themselves. The Ministry, along with the Health Administration, urged “groups” to disinfect drinking water, educate cooks on disinfection methods, and provide serving chopsticks for group meals. Individuals also had the responsibility to get vaccinated, not allow flies near food, and boil water before drinking.113

The central government sought to ensure that knowledge about the dangers of an outbreak of a disease like cholera, in addition to constant reminders of warfare, was top of mind. May 25, 1943 was designated as a city-wide cleaning campaign day. In the spirit of the Fuzhou and Shanghai cholera parades, the health bureau of Chongqing prepared posters, coordinated promotional teams equipped with loudspeakers, and vaccination vans. This campaign required active participation from all residents to reach certain cleaning goals.114 A key goal of the event, according to the host organization the Ministry of Education, was so that “promotion and real life need to be closely aligned,” such that participation in hygiene competitions must be seen as a form of wartime service itself. For mass vaccinations and promotional materials to have their maximum impact for “increasing wartime strength,” hygiene promotion needed to be practical.115

Mass-participation cleaning campaigns were common in wartime China in a variety of different public spaces, as refugees, schools, government apparatuses, and intellectual resources moved westward. For all such campaigns, multi-media promotional materials were widely encouraged by sponsoring government bodies. Songs, posters, lectures, and news articles were all valuable resources. Based on the National Health Administration guidelines, “Each central theme can be expressed through variations of different slogans … they can be posted to dining places, public transport stations, and other appropriate sites.”116 Posters educating the public about the dangers of cholera appeared around Chongqing. One poster shows a fly with a Japanese Rising Sun emblem, with slogans on the side reading “We need to prevent cholera and kill flies: and if you want to survive, kill the Japanese soldiers … If you don’t kill it, it will kill you.”117 In another image, a fly is depicted as a fighter jet that drops bombs labeled “cholera” onto a crowd of people. Numerous other flies are lined up behind the first.118 A picture of two missiles heading towards a populated Chongqing was captioned, “Air raids are scary, cholera is scarier!”119

Was the sudden resurgence of cholera in crowded wartime environments, and government reaction through mass vaccination and education campaigns, proof that not enough had been done to prepare the Chinese public in their daily lives? If the number of cholera cases in a major city like Chongqing had really dropped to seven in the entire year of 1941, perhaps the joint efforts of vaccination, sanitation, and increased public awareness were really making a difference.120 The mass migration into internal China brought refugees and crowding, but also educated personnel from China’s cities. The “émigré intellectuals” at the National Southwestern Associated University, a provisional wartime campus in Kunming incorporating students and staff of several Beijing-area universities, launched their own crusade for “local betterment” through a fly extermination campaign when they realized that their local business proprietors did not hold their restaurants to the same high levels of hygiene standards.121

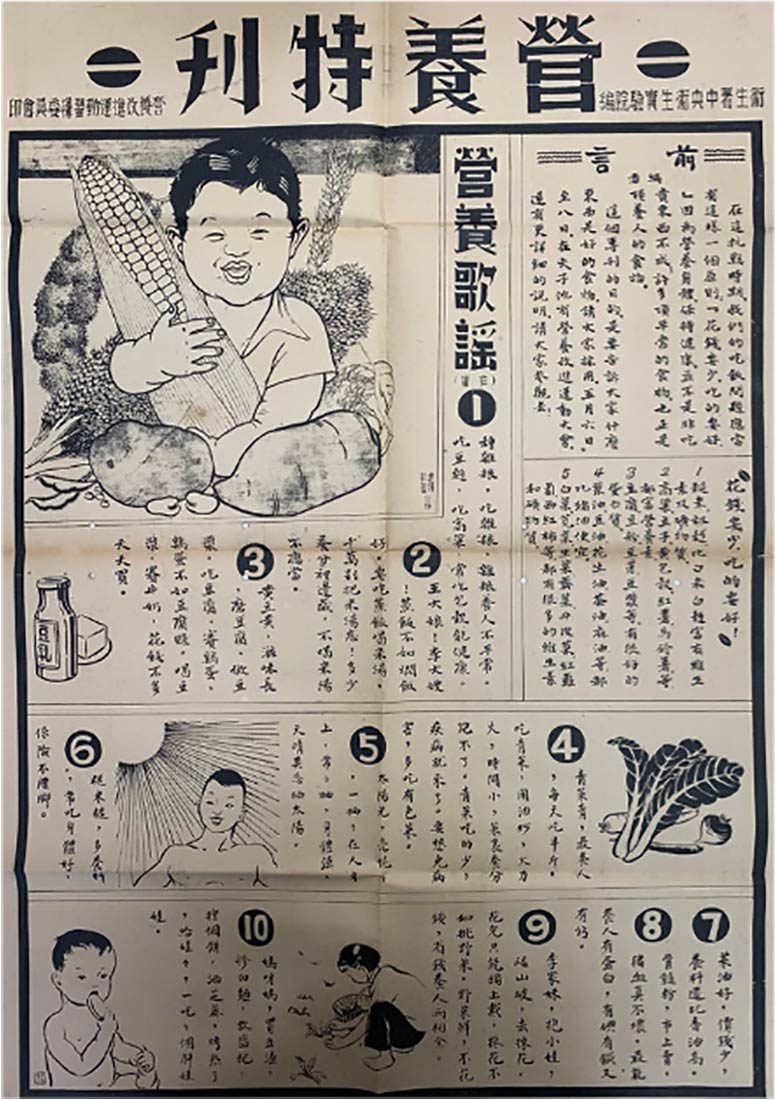

While the government’s public campaigns began a renewed effort for public sanitation and cholera-prevention, they could not be separated from continued calls to pay attention to both nutrition and frugality in the kitchen, all neatly all falling under the “dietary hygiene” umbrella. The municipal health bureau of Chongqing established its “nutritional hygiene consultation station” at the site of the capital post office, which administered advice and grain provisions as well as health check-ups and vaccinations.122 The Chongqing Health Bureau held a series of “Nutrition Advancement Movement” exhibitions in 1941, collaborating with local universities and factories, and the local New Life Movement model district. Attendees could watch plays, attend lectures, see farming displays from universities, and participate in mass performances of songs written for the occasion. The motto of the longest campaign held from May 5 to 8 was clearly influenced by wartime messaging: “we must spend little money and eat well” (huaqian yao shao, chi de yao hao 花錢要少,吃的要好). "To nourish bodies and maintain health we do not need expensive foods. Rather, there are many excellent common [modest] foods, which are also nourishing.” Suggestions for substituting tofu and peanut oil for animal products were made into catchy rhymes and became part of the promotional material. If participants followed the Movement’s guidelines for making “bean dregs pancakes,” they could also achieve something unheard of during wartime—helping their children become “plump.”123

After the success of the May events, the National Hygiene Laboratory also announced its training of dietary managers (shanshi guanli yuan 善食管理員) in nutrition basics, environmental hygiene, kitchen sanitation, food management, and other topics for respective workplaces, reinstituted during wartime. In keeping with the National Health Administration’s recommendation to promote “common foods” (tongsu shipin 通俗食品) and a do-it-yourself attitude during wartime, the Ministry of Agriculture’s experimental department produced a booklet of simple recipes of “everyday foods” (richang shipin 日常食品) with categories for “beans,” “vegetables,” and “pickles,” among others.124 Chiang Kai-shek’s own simple diet—“mostly made up of vegetables with very little fish and meat”—was held up as a patriotic example at the celebrations for the seventh anniversary of the launch of the New Life Movement in 1941; the same event also featured an agricultural produce competition in which university and school teams showcased how they could easily mill flour or process soy sauce and sugar.125 In Guangzhou, the YWCA organized a weeklong “Nutritional Cafeteria” (yingyang shitang 營養食堂) in February 1943, an exhibition and educational campaign demonstrating the innovation and the nutritional and monetary value of soybeans as a valuable food source.126

Wartime conditions required an overhaul of recipe and cooking guides that had been circulating in Chinese society. The commercial abundance of health products, supplements, and luxury food items of previous decades helped to instill and foster awareness of nutrition, but it is doubtful that the products advertised in various health publications were used widely, especially after supply lines were disrupted. Government agencies, charities, and other institutions became sources for nutritional advice; a father of a five-year-old with nutritional deficiencies wrote to ask the Chongqing Bureau of Health if there were any cheaper alternatives to fish liver oil, as it was too expensive to consume during wartime.127 More than sixty thousand pamphlets were produced by the National Health Administration to be distributed around Chongqing, including twenty thousand copies of “Methods to make up for nutritional deficiencies in soldiers during wartime.”128 The emphasis in food and cooking guides changed from glorifying variety to underscoring frugality.

Innovation in food and dietary advice also fostered rational interest in personal health and its implications for the national war effort. Like American and British counterparts, the Chinese Ministry of Food turned to innovation to produce dehydrated food products—“soup powder, crystallized soy sauce … corn bricks, wheat bricks”—for both army and general population use.129 The Refugee Children’s Committee, a private organization formed in 1937 to provide nutrition relief in Shanghai, adapted its recipes for soy milk and “bean dregs cakes” to be used in individual homes. Spurred by the influx of refugees into Shanghai after 1937, the Committee and its successor, the national China Nutritional Aid Council, “scientifically” transformed soybeans from a cheap ingredient to the best source of both nutrition and a tool for hygiene education.130 By 1940, the Council had expanded its operations to six distribution centers in the Chinese interior, with financial aid from the international charity organizations as well as the Chinese government.131

To a large extent, the promotion and popularization of soy milk and other “common foods” during and at the start of the New Life Movement both helped, and was made possible by, charitable work to provide food for China’s refugees. But despite clear plans and sufficient support for such work, Chinese “nutritional activists” during wartime still found themselves facing issues of supply. While soybeans, vegetables, and other cheaper foodstuffs had been promoted widely, wartime shortages made the provision of some products often unsustainable. Arthur N. Young of the China Nutritional Aid Council wrote to the food administration in Chongqing and the Council’s plans for producing “soy milk powder” hit a barrier when its flour provision by the government was suddenly cut in half.132 The Ministry of Food, established in 1940 to facilitate food distribution during the war, received petitions from Chongqing’s Chin Tong Street Municipal Hospital, the Chongqing Food Supply Office, and the Association for the Advancement of Children’s Nutrition for bags of flour to mix with the soy bean powder they already had.133 Nutritional reformists acted now on two fronts—charity to make up for nutritional deficiencies for the most vulnerable members of society, and also continuing their public education initiatives to ensure that Chinese families could replicate “scientific nutrition” in their own households. While independent organizations and reformists took leading roles in nutrition-related projects as the war continued, and the central government seemed to refocus its efforts on epidemic prevention, both sets of efforts largely went hand in hand. The government-sponsored nutrition campaigns, in addition, were clear signs that the individual kitchen became simultaneously a space for sanitation, nutrition, war effort contributions, and general progress. The war had accelerated the urgency for implementing more kitchen hygiene and nutrition developments, but the infrastructure, interest, and popular and commercial activities were already abundant.

Conclusion

In late 1945 and early 1946, representatives from China were invited to join the advisory council of the Sussex-based International Nutrition Institute and to send a delegation to a food technology conference at the New York-based Institute for Food Technologies. The central government also responded quickly to requests from the League of Nations to share food and agricultural production information.134 China was now a recognized and important participant in nutritional hygiene and dietary technological innovation, not to mention a respected member of the victorious Allies. In addition, cholera prevention and treatment methods seemed to become efficiently streamlined, and overall cases diminished.

In this immediate postwar period, new guides published for dietary hygiene reflected possibilities for a new type of scientific and cosmopolitan ideal kitchen in peacetime. In 1946, the Commercial Press translated a dietary guide intended for “achieving the urban, middle-class and above experience.” The author chastised the previous generation of nutrition experts, who, fearful that industrial advances would take away foods’ precious natural value, “bitterly” directed everyone to return to unprocessed, “ancient foods” (yuanshi shipin 原始食品). Doing so, the author wrote, “would bring us to dismiss all of our development and return to barbarism.” With vitamin synthesis, the author argued that human progress need not be confined to nor hindered by rigid dietary restrictions but should allow for flexibility and experimentation.135 A faculty member from the National Central University chemistry department and experienced nutrition columnist wrote that instead of using specific products as emergency supplements for unhealthy persons, the pursuit of nutrition should be part of everyday life, three meals a day.136 A product like soy milk would now need to find a place within everyday Chinese diets as a healthy addition to prevent “endemic nutritional deficiencies.”137

In much the same way, the practices of drinking hot, boiled water and using fly screens became basic household habits, the former a particular source of cultural distinction and pride even in modern-day China, where vacuum-sealed thermoses are ubiquitous. Today, cholera is neither top of mind nor politically relevant. The most common explanation about why the Chinese drink boiled water is that they have been doing it for 4,000 years, with hardly any mention about the quality of the available water in Chinese households, disease prevention, or socio-political implications. In spite of the absence of public historical knowledge about the practice’s recent history, the universal drinking of boiled water has become an example of national virtue-signaling and expectations of Chinese citizenry, in many ways similar to how soybeans were to be consumed in the 1930s. With this uniform practice, China had continued to take the lead on kitchen hygiene innovation through mythologizing and appropriating supposed ancient, yet “scientific,” wisdom. The path to victory of the Chinese over its long-standing enemies: cholera, jiaoqi, tuberculosis, and the Japanese, was self-evident, cost efficient, and would increase national strength in the face of adversity. More importantly, it allowed each individual to become part of scientific innovation through pursuing a hygienic and nutritious kitchen space.

Bibliography

Andrews, Bridie and Mary Brown Bullock, eds. Medical Transitions in Twentieth-Century China. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014.

Barrett, David P. and Larry N. Shyu, eds. China in the Anti-Japanese War 1937–1945: Politics, Culture and Society. New York: Peter Lang, 2001.

Bay, Alexander R. Beriberi in Modern Japan: The Making of a National Disease. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2012.

Bégin, Camille. Taste of the Nation: The New Deal Search for America’s Food. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016.

Brazelton, Mary Augusta. Mass Vaccination: Citizens’ Bodies and State Power in Modern China. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019.

Chen, Yong. Chop Suey, USA: The Story of Chinese Food in America. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

China Medical Journal (Shanghai), 1917–1920.

The China Press (Shanghai), 1921–1940.

Council on Health Education. “Weisheng tu hua” 衛生圖話 [Health picture talks]. Zhonghua weisheng jiaoyuhui xiao congshu zhi sanshier 中華衛生教育會小叢書之三十二 [Council on Health Education reference books no. 32]. Shanghai: YMCA Press at No 4. Kunshan Road, [undated].

Crook, Tom. Governing Systems: Modernity and the Making of Public Health in England, 1830–1910. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016.

Ferlanti, Federica. “The New Life Movement at War: Wartime Mobilisation and State Control in Chongqing and Chengdu, 1938—1942.” European Journal of East Asian Studies 11. 2012): 187–212. DOI: 10.1163/15700615-20121104.

---.“The New Life Movement in Jiangxi Province, 1934—1938.” Modern Asian Studies 44, no. 5. 2010): 961–1000. DOI: 10.1017/S0026749X0999028X.

Fu, Jia-Chen. The Other Milk: Reinventing Soy in Republican China. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018.

Funv Jie 婦女界 [Women’s world], 1941.

Hamlin, Christopher. Cholera: The Biography. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Hanson, Marta. Speaking of Epidemics in Chinese Medicine: Disease and the Geographic Imagination in Late Imperial China. New York: Taylor and Francis, 2012.

Hay, William Howard. Health via Food: Sun-Diet way to Health. East Aurora: Sun-Diet Health Foundation. 1933.

Health (Shanghai), 1924–1926.

Hillier, S. M. and J. A. Jewell, Health Care and Traditional Medicine in China 1800–1982. London: Routledge, 1983.

Hu Huafeng. Jiachang weisheng pengtiao zhinan 家常衛生烹調指南 [Home Hygienic Cooking Guide]. Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1932.

Inoue Kaneo. Yangsheng xue yao lun 養生學要論 [Essentials of health]. Trans. Zhu Jianxia. Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1946.

Israel, John. Lianda: A Chinese University in War and Revolution. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Jackson, Isabella. Shaping Modern Shanghai: Colonialism in China’s Global City. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Latour, Bruno. The Pasteurization of France. Trans. Alan Sheridan and John Law. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Lary, Diana. The Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Lei, Sean Hsiang-lin. “Habituating Individuality: The Framing of Tuberculosis and Its Material Solutions in Republican China.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 84, no. 2. Summer 2010: 248–279. DOI: 10.1353/bhm.0.0351.

Nakajima, Chieko. Body, Society, and the Modern State: The Creation of Public Health and Urban Culture in Shanghai. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Neizheng gongbao 內政公報 [Ministry of the Interior Bulletin] (Nanjing), 1928–1937.

Peter, William Wesley. Broadcasting Health in China: The Field and Methods of Public Health Work in the Missionary Enterprise. Shanghai: Presbyterian Mission Press, 1926.

Roberts, J.A.G. China to Chinatown: Chinese Food in the West. London: Reaktion Books, 2004.

Rogaski, Ruth. Hygienic Modernity: Meanings of Health and Disease in Treaty-Port China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Quchu wencang yundong 驅除蚊蒼運動 [Fly elimination campaign]. Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1934.

Schneider, Helen. Keeping the Nation’s House: Domestic Management and the Making of Modern China. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2011.

Shiyan Weisheng Qi Kan 實驗衛生期刊 [Experimental hygiene quarterly journal] (Kunming), 1943.

Smith, Hilary. Forgotten Disease: Illnesses Transformed in Chinese Medicine. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017.

Smith, Virginia. Clean: A History of Personal Hygiene and Purity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Sutphen, Mary P. “Not What, but Where: Bubonic Plague and the Reception of Germ Theories in Hong Kong and Calcutta, 1894–1897.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 51, no. 1. (Jan 1997): 81–133. DOI: 10.1093/jhmas/52.1.81.

Swislocki, Mark. Culinary Nostalgia: Regional Food Culture and the Culinary Experience in Shanghai. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009.

Watt, John R. Saving Lives in Wartime China: How Medical Reformers Built Modern Healthcare Systems Amid War and Epidemics, 1928—1945. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

Weisheng yue kan 衛生月刊 [Health monthly] (Shanghai), 1934—1936.

Xinshenghuo zhou kan 新生活週刊 [New life weekly], 1934.

Xing hua 興華 [Chinese Christian advocate], 1934.

Zhang Enting, Yin shi yu jiankang 飲食與健康 [Food and health]. Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1936.

Zheng Ji, Shiyong yingyang xue 實用營養學 [Practical nutrition studies]. Nanjing: Zhengzhong Shuju: 1947).

Archives Consulted

Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow, NY.

China Medical Board Inc, FA065.

Rockefeller Foundation Records, China Medica Board Records, RG4.

International Health Division, RG4/Series 601.

International Health Division, RG 5/Series 601

Second Historical Archive of the People’s Republic of China, Nanjing, China.

Ministry of Interior files, 1001.

Ministry of Education files, 5/1925, 5/1927.

Academia Historica, Taipei, Taiwan.

Archives of Yan Xishan, 116.

Executive Yuan, National Health Administration, 028.

Ministry of Education, 019.

Ministry of Transport, 017.

Ministry of Food, 119.

Kuomintang Party Archives, Taipei, Taiwan

“Weisheng shu weisheng gongluzhan gezhong diaocha jilubiao” 衛生署衛生公路站各種調查紀錄報 [Various information and investigation forms for the National Health Administration Highway Health Station]. 1931. 502/26.

“Chongqing shi weisheng ji fangyi” 重慶市衛生及防疫 [Hygiene and disease prevention in Chongqing]. July 1939. 003/0240.

“Weishengshu yifang bibao” 衛生署醫防壁報 [National Health Administration posters about medicine and defense]. 502/90.

Rare Books and Manuscripts, Medical Historical Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

“Album of Photographs Illustrating the Work of the National Health Administration, Nanking, China.” 1931

Koh, Z.W. “The Tiger Is Coming: Methods for Preventing Cholera.” 1927.

Charles-Edward Amory Winslow Papers, MS749.

Shanxi Provincial Library Rare Books and Special Collections, Taiyuan, China.

Historical Photographs of China, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. www.hpcbristol.net.

“Anti-Japanese public hygiene banner.” circa 1938.

Endnotes

1 “Pictures of Foochow Anti-Cholera Campaign,” [undated]. Yale University Medical Library Special Collections (henceforth “Yale”), New Haven, CT.

2 J. E. Gossard, “Anti-Cholera Campaign in Foochow,” China Medical Journal 34 (1920): 667.

3 “How to Cook Vegetables,” Health 1, no. 2, (June 1924): 32.

4 Ruth Rogaski, Hygienic Modernity: Meanings of Health and Disease in Treaty-Port China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

5 Tom Crook, Governing Systems: Modernity and the Making of Public Health in England, 1830—1910 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016), 4.

6 Helen Schneider, Keeping the Nation’s House: Domestic Management and the Making of Modern China (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2011), 14, 109.

7 Ibid., 42.

8 Christopher Hamlin, Cholera: The Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 73

9 Hamlin, Cholera, 234.

10 “Cholera and China’s Susceptibilities,” The China Weekly Review, 28 August 1926.

11 J. A. G. Roberts, China to Chinatown: Chinese Food in the West (London: Reaktion Books, 2004), 82—83; Memorandum on Hospital economics/charges, 30 November 1937. Rockefeller Archive Center (henceforth “RAC”)/CMB Inc/FA065/Box 68/Folder 483, Sleepy Hollow, NY.

12 Gossard, “Anti-Cholera Campaign in Foochow,” 668.

13 “President Hsu and Family Interested in Health Films,” The China Press, 20 September 1921.

14 “Report of the Hwa Mai Hospital, Ningpo, 1919,” China Medical Journal 34 (1920): 674.

15 Peter, Broadcasting Health in China, 8.

16 Ibid., 55.

17 Chieko Nakajima, Body, Society, and the Modern State: The Creation of Public Health and Urban Culture in Shanghai (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018), 130.

18 “China National Health Administration Album 1931,” Yale.

19 S.M. Hillier and J. A. Jewell, Health Care and Traditional Medicine in China 1800—1982 (London: Routledge, 1983), 41. Federica Ferlanti, “The New Life Movement in Jiangxi Province, 1934—1938,” Modern Asian Studies 44, no. 5 (September 2010): 982.

20 Shi Cui, “Tantan xialing de yinshi 談談夏令的飲食” [A discussion about diet in the summer], Weisheng yue kan 衛生月刊 19 (June 1934): 16.

21 “Weisheng tu hua” 衛生圖話 [Health picture talks], Zhonghua weisheng jiaoyuhui xiao congshu zhi sanshier 中華衛生教育會小叢書之三十二 [Council on Health Education Reference Books], no. 32 (Shanghai: No 4. Kunshan Road, [undated]). See Figure 1.

22 Bi Yun, “Shanghai de cesuo yu chufang”上海的廁所與廚房 [Toilets and kitchens in Shanghai], Weisheng yue kan 19: 26—27.

23 Department of Health, City of Hangchow, “Hu lai le” 虎來了 [The tiger is coming: Methods for preventing cholera], 1927.

24 “Guomin zhengfu neizhengbu chufu ying shou guize” 國民政府內政部廚夫應守規則 [Regulations that chefs should abide by from the National Government Ministry of the Interior], Announcement no. 178, Neizheng gongbao 內政公報 [Ministry of the Interior Bulletin] 1, no. 2 (May 1928): 110.

25 “Guomin zhengfu neizhengbu chufu ying shou guize,” 111.

26 “Weisheng shu weisheng gongluzhan gezhong diaocha jilubiao” 衛生署衛生公路站各種調查紀錄報 [Various information and investigation forms for the national health administration highway health station], 1931. Kuomintang Party Archives (henceforth “KMT Archives”) 502/26, Taipei, Taiwan.

27 “Weisheng: Bugao: Shantou shizhengfu guanli jiulou fandian chaju weisheng guize” 衛生:佈告:汕頭市政府管理酒樓飯店茶居衛生規則 [Notice: Shantou government regulations for hygiene of restaurants and teahouses], Shantou shi shizheng gongbao 汕頭市政公報 [Shantou municipal bulletin] 65, 1931.

28 “Weisheng siaoxi: Chacan lvguan fandian weisheng” 衛生消息:查參旅館飯店衛生 [Hygiene news: Inspection of hotel and restaurant hygiene], Shoudu shizheng gongbao 首都市政公報 [Governance bulletin of the capital city] 53, 1930.

29 “Hu lai Le.”

30 Shi, “Tantan xialing de yinshi,” 16.

31 Marta Hanson, Speaking of Epidemics in Chinese Medicine: Disease and the Geographic Imagination in Late Imperial China (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2012), 136.

32 Qiu Chuanfang, “Huoluan ‘hu lie la’ qian shuo” 霍亂“虎來了”前說 [Cholera Briefing], Weisheng yue kan 19: 19.

33 “Weisheng tu hua,” 3.

34 Peter, Broadcasting Health in China, figure 27, 39.

35 John B. Grant, “Fly and Mosquito Control in Nanjing,” 19 January 1924. RAC/International Health Division/RG4/Series 601/FA 115/Box 55/Folder 348.

36 Shi, “Tantan xialing de yinshi,” 17.

37 Jiangsu shengli Zhenjiang minzhong jiaoyu guan: Yinshui weisheng yingpian shuxue fangan 江蘇省立鎮江民眾教育館:飲水衛生影片數學方案 [Jiangsu Province Zhenjiang People’s Education Center: Arrangements on how to create the drinking water hygiene slideshow], 1930. Shanxi Provincial Library Rare Books and Special Collections, Taiyuan, China.

39 “Hu lai le.”

39 Jiangsu shengli Zhenjiang minzhong jiaoyu guan.

40 Grant, “Fly and Mosquito Control in Nanjing.”

41 “Hu lai le.”

42 “Shimin de shuguang: Weisheng: Chufang nei zhi qingjie fa, mie sheng zhe zhuyi” 市民的曙光:衛生:廚房內之清潔法,滅繩者注意 [Dawn of the city resident column: Hygiene: Methods for kitchen hygiene, focus on fly elimination], Guangzhou shi shizheng gongbao [Guangzhou City Public Bulletin] 82 (1932): 14.

43 Health 1, no. 1, March 1924.

44 Grant, “Fly and Mosquito Control in Nanjing.”

45 “Report of the Peking First Health Station for 1930,” 30 September 1930. RAC/CMB Inc/FA065/Box 67/Folder 471.

46 “Guoli Di Erishier Zhongxuexiao ben bu ji yi er liang fenxiao zhengjie shishi qingxing” 國立第二十二中學校本部及一二兩分校整潔實施情形 [Cleanliness of the 22nd Public Middle School and two affiliate schools], March 1943. SHAC 5/1927 (2).

47 “Shimin de shuguang,” 14.

48 Quchu wencang yundong 驅除蚊蒼運動 [Fly elimination campaign], (Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1934), 15.

49 Ibid., 15.

50 Bruno Latour, The Pasteurization of France, trans. Alan Sheridan and John Law (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988), 19–20.

51 “Shimin de shuguang.”

52 Virginia Smith, Clean: A History of Personal Hygiene and Purity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 299–300

53 “Correct Ways to Cook Vegetables,” Health 1, no. 2 (June 1924): 32.

54 Hu Huafeng, Jiachang weisheng pengtiao zhinan 家常衛生烹調指南 [Home hygienic cooking guide] (Commercial Press: 1932), 3.

55 “Jieshao kuangyan lei he duzhe jianmian” 介紹礦岩類和讀者見面 [Introducing readers to minerals], Weisheng banyue kan 5, no 5 (May 1935): 265.

56 Hu, Jiachang weisheng pengtiao zhinan, 1.

57 “Jiating weisheng: Chufang shebei” 家庭衛生:廚房設備 [Household hygiene: Kitchen facilities], Xinghua 31, no. 25 (1934): 17.

58 Zhang Enting, Yinshi yu jiankang 飲食與健康 [Food and health] (Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1936), 2.

59 Camille Bégin, Taste of the Nation: The New Deal Search for America’s Food (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016), 158.

60 Yong Chen, Chop Suey, USA: The Story of Chinese Food in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), 157.

61 Mark Swislocki, Culinary Nostalgia: Regional Food Culture and the Culinary Experience in Shanghai (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 136.

62 Chen, Chop Suey, 157.

63 Ibid., 160–161.

64 Zhang, Yinshi yu jiankang, 185.

65 Shiu Wong Chan, The Chinese Cook Book (1917), in Chen, Chop Suey, 167.

66 Sean Hsiang-lin Lei, “Habituating Individuality: The Framing of Tuberculosis and Its Material Solutions in Republican China,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 84, no. 2. (Summer 2010): 248–279, 263.

67 “The Fight Against Tuberculosis,” The China Press, 12 November 1936, 10.

68 Wu Lien-teh, “A Hygiene Chinese Dining Table,” National Medical Journal of China 1, no. 1 (1915), 7–8. Lei, “Habituating Individuality,” 264.

69 Lei, “Habituating Individuality,” 266.

70 Lu Liuhua, “Tantan weisheng kuai de libi” 談談衛生筷的利弊 [Discussing the advantages and disadvantages of hygienic chopsticks], Weisheng yue kan (June 1934): 22–23.

71 Lu, “Tantan weisheng kuai de libi.”

72 Wang Zude, “Weisheng changshi: Gongshi zhi e’xi” 衛生常識:共食之惡習 [The evil custom of communal eating], Xinshenghuo zhou kan 新生活週刊 [New life weekly] 1, no. 14 (1934): 12.

73 Hilary Smith, Forgotten Disease: Illnesses Transformed in Chinese Medicine (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017), 87.

74 Ibid., 96.

75 Ibid., 116–7.

76 “Jiaoqi Beriberi” 腳氣, Qiba qi kan 汽巴期刊 [Ciba quarterly journal] 5 (1936): 248.

77 Alexander R. Bay, Beriberi in Modern Japan: The Making of a National Disease (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2012), 9.

78 Rogaski, Hygienic Modernity, 253.

79 “China Medical Missionary Conference,” The British Medical Journal (1915): 809.

80 Jiang Tiyuan, “Jiaoqi bing de zhengzhuang zhiliao ji qi yufang fangfa” 腳氣病的症狀治療及其預防方法 [Symptoms, treatment, and prevention methods of jiaoqi], Weisheng yue kan 5, no 12 (December 1935): 38.

81 Zhang, Yinshi yu jiankang, 1.

82 Swislocki, Culinary Nostalgia, 187.

83 Schneider, Keeping the Nation’s House, 138.

84 Wang Chengfa, “Xuesheng yingyang weisheng wenti” 學生營養衛生問題 [The problem of nutritional hygiene for students], Shiyan weisheng qi kan 實驗衛生期刊 [Experimental hygiene quarterly journal] 1, no. 3–4 (1943): 19.

85 Jia-Chen Fu, The Other Milk: Reinventing Soy in Republican China (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018), 47.

86 Jiang, “Jiaoqi Bing de zhengzhuang zhiliao ji qi yufang fangfa,” 38.

87 “Weisheng wenda” 衛生問答 [Hygiene Q and A], Weisheng yue kan 1934: 18.

88 Jiang, “Jiaoqi bing de zhengzhuang zhiliao ji qi yufang fangfa,” 39.

89 See Federica Ferlanti’s studies of the importance and success of the Movement’s lasting impact on Chinese society and its institutions as crucial for wartime mobilization. Federica Ferlanti, “The New Life Movement at War: Wartime Mobilisation and State Control in Chongqing and Chengdu, 1938–1942,” European Journal of East Asian Studies 11 (2012): 187–212. Federica Ferlanti, “The New Life Movement in Jiangxi Province, 1934–1938,” Modern Asian Studies 44, no. 5 (2010): 961–1000.

90 Chiang Kai-shek, “Xinshenghuo guize” 新生活規則 [Guidelines of the New Life Movement], Shanxi gongbao 山西公報 [Public Bulletin of Shanxi], 1934.

91 “Xinshenghuo yundong tu jie” 新生活運動圖解 [Pictorial explanations of the New Life Movement], Xinshenghuo zhou kan 新生活週刊 [New life weekly] 1, no. 10 (1934): 1.

92 “Amah-Education Nanjing Plan,” The China Press, 17 July 1936. Even within Jiangxi, the New Life Corps were “independently established organizations.” While all mandated to spread New Life ideas, there were variations and different adaptations. Ferlanti, “The New Life Movement in Jiangxi Province,” 975.

93 Schneider, Keeping the Nation’s House, 42–44.

94 Fu, The Other Milk, 33.

95 Ying Ming, “Huangdou de yingyang jiazhi” 黃豆的營養價值 [The nutritional value of soybeans], Weisheng zazhi 衛生雜誌 [Health magazine] 4, no. 2 (1936): 25.

96 Julean Arnold, “The Soybean ‘Cow’ – of China,” The China Press, 9 March 1940.

97 Ying, “Huangdou de Yingyang Jiazhi.”

98 Arnold, “The Soybean ‘Cow.’”

99 Fu, The Other Milk, 36.

100 Xiao Dongfeng, “Doujiang bi niuru hao” 豆漿比牛乳好 [Soy milk is better than cow’s milk], Funv jie 婦女界 [Women’s world] 2, no. 10 (1941): 8.

101 “Doujiang ke dai rennai” 豆漿可代人奶 [Soy milk can replace human milk], Xinghua 32, no. 20 (1935): 19–20. “Na doujiang lai daiti renru” 拿豆漿代替人乳 [Use soy milk as a replacement for human milk], Jiaoyu duanbo 教育短報 [Short newspaper of education] 27 (1935): 18.

102 “Women Told Food Value of Soybean: Dr. Webber Says It Excels Milk, Meat,” The China Press, 20 January 1937.

103 Ying, “Huangdou de yingyang jiazhi.”

104 Wang, “Weisheng changshi: Gongshi zhi e’xi,” 12.

105 “The Wartime Food-Supply Situation in China,” Foreign Agriculture 8, no. 5 (1943): 102.

106 Jin Pusen, “To Feed a Country at War: China’s Supply and Consumption of Grain During the War of Resistance,” in China in the Anti-Japanese War 1937–1945: Politics, Culture and Society, ed. David P. Barrett and Larry N. Shyu (New York: Peter Lang, 2001), 157–69.

107 “Chongqing shi weisheng ji fangyi” 重慶市衛生及防疫 [Hygiene and disease prevention in Chongqing], July 1939. KMT Archives/003/0240.