Demystifying Remote Research in Anthropology and Area Studies

References | Author Bio | ![]() Download the PDF

Download the PDF

Keywords: digital ethnography; anthropology; remote research; fieldwork; COVID-19

Introduction

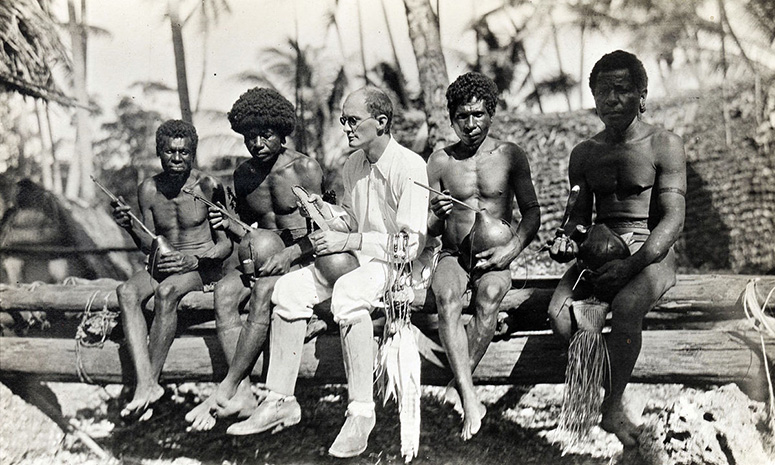

A year or two ago, I routinely fought back a wave of anxiety whenever a colleague inquired about my field of research. I would reply with something to the effect of: “I am a digital anthropologist studying transnational online Shinto communities.” My elevator pitch was often met with a mix of fascination, confusion, or outright skepticism. Colleagues would ask me things like: “‘Transnational online Shinto’—is that really a thing? How does that work? You’ll still conduct fieldwork in Japan to earn your chops, right? How will you explain yourself to funding organizations and hiring committees? Are you sure you’re not secretly an Americanist?” These questions, though well-meaning in most cases, never failed to hit a number of disciplinary nerves. Since the hoary origins of traditional anthropological fieldwork when Bronisław Malinowski (1884-1942) set sail for the Trobriand Islands,1 practitioners have prided themselves on “being there” in the hallowed fieldsite,2 physically and psychically embedded in the everyday lives of one’s research subjects for an extended period of time.3 What sort of proper anthropologist of all things Japan could I be, sitting in any location with my laptop propped up somewhere, presumably surfing the web and Facebook-stalking strangers?

Since the global COVID-19 pandemic disrupted virtually every aspect of our personal and professional lives in early 2020, responses to my work have changed dramatically. Colleagues now make wistful comments, tinged with discouragement and sometimes a bit of jealousy: “You are so lucky to be studying the Internet. Your work must be largely unaffected by the pandemic. How does that work? I don’t know where to start.” Regrettably, I must admit to not having a magic bullet methodology to share with my friends who are historians and literary scholars. Digital anthropology in many respects remains quite a niche subdiscipline. However, in reflecting on my own experiences and comparing notes with my colleagues, I’ve found that the anxieties that digital ethnographers have wrestled with as a fundamental part of our brand of research are not so unique. These questions, misgivings, and scholars’ strategic responses highlight a number of implicit and essential assumptions that I believe we all have internalized to some degree,4 namely that remote research is: 1) either too recent a phenomenon or a relic of academia’s antediluvian past; 2) not sufficiently rigorous; and 3) does not produce valuable knowledge in and of itself.5

If you find the proposition of adopting remote research methods daunting, unsettling, overwhelming, or even objectionable, you are in good company. But in order to decide if, when, and how we ought to go about research at a distance, we must begin by naming, contextualizing, and confronting what it is that makes us uncomfortable with the theory and practice of remote research. To this end, in this essay I will explore anthropology’s founding mythos and a few key debates within the discipline concerning our orientation toward remote research. I will demonstrate that remote research is neither new nor necessarily outdated. Moreover, I will make the case that remote research can be rigorous and valuable to the project of producing knowledge. I will conclude by suggesting that we should strive in this moment not simply to adapt and adopt remote research as a temporary fix until we can resume business as usual, but to integrate it into our disciplinary frameworks as a legitimate and valuable mode of research.

Remote Research Past and Present

Modern anthropology can be said to have begun with a kind of remote research as its primary method. But the discipline’s founding mythology relies upon a triumphant narrative of linear progression away from remote methods and toward in situ fieldwork exemplified by the ethnographic method par excellence, participant observation. The tale begins in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with the practice dismissively referenced as “armchair anthropology.”6 Founding figures such as E. B. Tylor (1832-1917) and James G. Frazer (1854-1941) did not travel to collect data firsthand, but rather drew upon a range of available texts and secondary sources such as reports from missionaries, colonial officers, merchants, and explorers. After a few decades, enterprising anthropologists shifted closer to the localities and cultures they wished to study by observing events and collecting informants’ accounts from a safe, comfortable distance on “the veranda” of a local Western host.7 Malinowski paints a vivid picture of this sort of researcher in his manifesto for a revolution in anthropological methods, which is worth quoting at length:

As regards anthropological field-work, we are obviously demanding a new method of collecting evidence. The anthropologist must relinquish his comfortable position in the long chair on the verandah of the missionary compound, Government station, or planter’s bungalow, where, armed with pencil and notebook and at times with a whisky and soda, he has been accustomed to collect statements from informants, write down stories, and fill out sheets of paper with savage texts. He must go out into the villages, and see the natives at work in gardens, on the beach, in the jungle; he must sail with them to distant sandbanks and to foreign tribes, and observe them in fishing, trading, and ceremonial overseas expeditions. Information must come to him full-flavoured from his own observations of native life, and not be squeezed out of reluctant informants as a trickle of talk. Field-work can be done first-or second-hand even among savages, in the middle of pile-dwellings, not far from actual cannibalism and head-hunting. Open-air anthropology, as opposed to hearsay note-taking, is hard work, but it is also great fun. Only such anthropology can give us the all-round vision of primitive man and of primitive culture.8

Who better to spark this research revolution than Malinowski himself? In one of the formative and most heavily mythologized moments in the history of anthropological methods in the early twentieth century, Malinowski distinguished himself from the previous generation by championing direct ethnographic fieldwork, centered on the new practice of participant observation. It is at this point that the fieldsite became the consecrated ground for the discipline’s most sacred rite of passage: ethnographic fieldwork. According to Clifford Geertz, it is through the experience of “be[ing] there” in the field for an extended period of time, the process of fashioning oneself into an instrument of social science data collection, and the performative reenactment of one’s deep engagement with the field in ethnographic writing that anthropologists stake their credibility and professional authority.9 Following this observation to its logical conclusion, if one cannot “be there” for a certain amount of time (one to two years is the gold, if arbitrary, standard) and attune themself to the intricacies of the field, then they do not meet the criteria to be considered a master of their profession.

Scholars of different disciplinary persuasions will likely recognize in the mythic origins of anthropology the origins of area studies as well. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, early armchair Orientalists synthesized various second-hand accounts from missionaries, merchants, and travelers, etc. Over time, scholars ventured to non-Western regions to conduct field research themselves and acquire regional expertise. Area studies, Orientalism’s successor as the academic study of the non-West, was formed over the latter half of the twentieth century in response to World War II and reached its height during the Cold War.10

No one can deny that there are many practical benefits to “being there” in the far-away field, including the acquisition of linguistic fluency, building personal and professional networks with locals, observing in-person (offline) events, and visiting archives that are not digitized or digitally accessible from abroad. But the just-so stories of direct and active ethnographic fieldwork eclipsing distanced and passive observation to become anthropology’s raison d'être and area studies replacing Orientalism obscure a number of finer points that we should consider.11

Humanistic research was facilitated by and complicit in the project of empire at every step in the evolution of these two fields.12 So-called armchair studies were fueled by the circulation of myriad reports of various colonial agents circulating within a global network designed to gather information and deliver it to the metropole. As European empires expanded, scholars were enabled to conduct fieldwork through the many privileges, protections, and institutional resources afforded them as colonizers, including increased military presence and the growth of colonial settlements.13 As Tessa Morris-Suzuki notes, colonial encounters and world wars highlighted “the strategic value of cultural knowledge: information about the languages, histories and traditions of geographically distant allies and enemies was vital to the conduct of war, and to the international power struggles of the Cold War world.”14

The turn from remote to in-person research methods in non-Western fieldsites was not the product of sudden methodological enlightenment, but of the demands and desires of Western empire for certain kinds of knowledge pertaining to “the other.” The “field” was not designed to be the mystical location for the researcher’s initiation into another perspective, culture, or reality, but an arena to be documented, known, and eventually conquered. Despite our attempts to escape the problematics of this history in the intervening decades by attending to fragmented fields and global circulations,15 this past continues to haunt us through our valorization of physical (i.e. offline), extensive, in-person fieldwork as the gold standard for humanities research and our uncritical skepticism of remote methods.

Something Old, Something New

Having traced the source of our misgivings concerning the practice of remote research to the influence of the Malinowskian mythos and the historical entanglement of scholarship with empire-making on the development of our methodological and epistemological frameworks, we can now examine in more detail the claims that remote research is either outdated or too new, does not meet standards for academic rigor, and is not valuable in and of itself. Let us begin with the first fallacy: that remote research is either a relic of the past or a newfangled fad. As mentioned above, our earliest academic ancestors conducted remote research through a carefully curated, collaborative network of informants and resources. Efram Sera-Shriar argues that rather than being satisfied with passively gathering data from untrained informants and making uninformed pronouncements from a distance, armchair anthropologists were “highly attuned to the problems associated with their research techniques and continually sought to transform their methodologies” according to the resources at their disposal.16 For example, in 1872 Tylor and a number of British anthropologists produced the first questionnaire for the nascent Anthropological Institute in order to provide a guide for traveling and native informants that would enhance the quality of the data collected.

During World War II and the Cold War, further turning points in the development of anthropology and area studies, Western scholars once again found themselves unable to safely travel abroad to fieldsites in places like Japan, Germany, and the Soviet Union to conduct their research and turned to media such as films, literature, and art.17 Half a century later, others have had to rely upon native informants during periods of great social unrest in countries like Afghanistan and Russia and track people’s experiences of areas rendered inaccessible due to natural disasters in real-time through online means.

Researchers undoubtedly have faced a variety of historical and personal circumstances that have limited their ability to travel abroad. In their call for the development of “patchwork ethnography,” Günel, Varma, and Watanabe note that “family obligations, precarity, other hidden, stigmatized, or unspoken factors—and now Covid-19—have made long-term, in-person fieldwork difficult, if not impossible, for many scholars.”18 However, these limitations and researchers’ responses largely have been overlooked as unfortunate anomalies born from extenuating circumstances. Surely, we may think to ourselves, the scholar in question would have conducted in-person fieldwork had they had the chance. But what, then, are we to make of researchers whose field sites are not physically located in one of our carefully fixed geographical areas of study? What of transnational and digital projects?

In recognition of the impacts of globalization and the “mobility turn,” anthropologists in the 1980s and 90s strove to account for flows of people, media, technology, capital, and ideas across physical and ideological boundaries.19 This line of inquiry productively destabilized the long-established primacy of the classical fieldsite—the village—and reimagined an approach to ethnographic fieldwork that is distributed across multiple fieldsites (i.e. multi-sited ethnography).20 While this paradigm shift toward an appreciation for the contingent and fragmented nature of the “field” reinvigorated theoretical and methodological discourse, the (Western) researcher’s mobility was once again taken for granted. The burden then fell to scholars to transform their research designs and grant applications to accommodate periods of time physically spent at a multiplicity of networked field sites.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, researchers began to explore another potential paradigm shift, this time technological in nature: the development of the Internet. Through various, ever-evolving forms of computer-mediated communication, people from all over the world could virtually inhabit the same space, whether it be a text-only forum, a multi-media social networking service, or even a three-dimensional virtual world. Opinions on pioneering research in digital anthropology tended toward extremes; either cyberspace was utterly devoid of meaningful human interaction deserving of study, or it presaged the death knell of tradition anthropology (even humanity) as we knew it. Critics even warned against falling back into old disciplinary habits and practicing armchair anthropology from behind one’s computer screen. After a few decades of further study, digital anthropologists and digital ethnographic methods gained enough recognition to be considered a subdiscipline, with several edited volumes and handbooks of method published in the last several years.21 Thus, rather than being the rare exception to the rule, remote research broadly speaking has been present since the founding of our field, and approaches to it continue to undergo a process of evaluation and refinement in response to the needs of the moment.

Field Notes

Like many remote or digital projects, my ethnographic research on transnational, online communities of Shinto ritual practitioners draws upon the strengths of both traditional anthropological methods and remote research depending on the affordances of a given situation. With my interlocutors living in different regions of the world and different time zones, synchronicity and physical co-presence are more often than not an impossibility regardless of social distancing and travel restrictions. The experience of interacting remotely is actually closer to their experience of community engagement. As such, participant observation remains the foundation of my data collection, but this observation takes place on and through the Internet, the same medium through with my research participants interact with each other. We meet with each other on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Reddit, and Discord. Interviews take place over video conferencing platforms like Zoom and, more often, in chat boxes and emails. I still take extensive fieldnotes, but they are located in mobile apps and superimposed on individual web pages through web archiving and annotation software.22 Like the nineteenth century armchair anthropologists, I also actively gather information from various indirect sources on the Internet, such as individuals' public accounts on blogs and social media and newspaper articles and their comments sections. Again, this practice of searching for or happening upon various relevant streams of information is one that I hold in common with my research participants. Testing the limits of what is gained and lost through the practice of remote research in place of, but more often in tandem with, in-person research presents us with opportunities to reflect on, clarify, and reimagine the utility of traditional methods in new circumstances.

Rigor Is Not Geographically Dependent

Having established that there is much precedent for remote research, if also avenues for further growth, it is here that we turn to the second fallacy of remote research: that it is not rigorous. Again, this assumption results from the value we place on the experience of “being there” in the field. According to Ulf Hannerz, despite new approaches to conducting qualitative research, the classic model of the single fieldsite “for very long remained more or less the only fully publicly acknowledged model for field work, and for becoming and being a real anthropologist.”23 During this period (lasting a year or two at first, part of a more prolonged engagement measured in decades) we are ideally isolated and immersed in our research, thinking on our feet and honing our skills. Upon our return, we tell our advisers, colleagues, and hiring committees—anyone we want to impress—that we went everywhere there was to go, saw everything there was to see, and participated in everything there was to do, to the best of our abilities. And thus, we emerge from this rite of passage tried-and-true experts in our field. But if we are honest with ourselves, this timeless narrative is not everything it is cracked up to be. What is worse, it deliberately overlooks a number of significant experiences that do not fit.

For one thing, “being there” in the field does not always guarantee access to the sources we desire. We may lack the right introduction. We may simply be refused entry into a particular archive or community. We may wind up based in another location due to contingencies like a host moving from one institution to another. There may be physical barriers barring access. Nowadays, we may be required to stay at home due to a lock-down. Then there are personal circumstances. We may not be able to attend an event because there was no available childcare. We may fall ill, wind up in the hospital, and require major surgery. We may be so overwhelmed and exhausted that we stay home for days. We may experience traumas we do not want to or cannot name. It happens more often than we like to admit, perhaps because it feels like failure; it does not live up to the ideal fieldwork experience. Even when there are no barriers to our research, we cannot be everywhere at once, much as we might like to be or present ourselves as having been (what John Postill refers to as the “ethnographic fear of missing out”).24 We choose to focus on certain people, certain networks, certain archives and corpora. If we attend an event on one side of town, we are not attending the myriad other events happening on the other side. The boundaries of our research flex to include or exclude what suits our purposes and is within our limitations. Total immersion is a myth.

Thus far I have tried to prove the negative: that “being there” in the field is not inherently more rigorous than other forms of research. But what of remote research’s merits? Online researchers like Patty Gray, John Postill, Crystal Abidin, and Gabriele de Seta have admitted to ongoing anxieties as they engage in remote research,25 asking themselves questions like: “Can I do anthropology this way? Am I allowed to do anthropology this way…? Can this be considered a legitimate form of… ‘real’ fieldwork? Or is it cheating because the ‘being there’ part is missing?”26 In response to these internal and external anxieties as to the validity of their research, digital anthropologists have demonstrated how it is entirely possible to “be there” immersed in the digital field and engaging in conversations and events on the same terms and at the same time as one’s research subjects.27 In fact, in some ways digital anthropologists can maintain a broader and more active presence through a variety of digital devices and social media platforms.28 At any given moment, I can share private conversations with several research subjects living on different continents, peruse archives of group discussion posts, and watch multiple ritual livestreams, all while cooking dinner for my family. Though researchers may interact with the field through a networked device while sitting at an office desk or (God forbid) in an armchair, they are not lazy or disconnected. They are active, and they are ‘present’ in different ways.29 As much of our work has shifted online due to the pandemic, I am sure we can all appreciate that this is vital, demanding, and honestly exhausting work.

Indeed, if we measure the rigor of digital research according to the applicability of traditional methods and epistemes, then this kind of remote research passes muster. However, Postill cautions against simply projecting (and thus reifying) the quintessential fieldsite and mandate for “being there” onto cyberspace of offline modes of research at a distance. He argues that “it is still possible to extract valuable insights from archived moments, even from moments that we never experienced live.”30 This statement likely will seem obvious to scholars of various disciplinary persuasions who study the past, but it is a controversial claim in ethnographic circles.

Freeing ourselves from the demands of constantly “being there” in the flesh and “being then” in the initial moment, Postill suggests that we can begin to explore other modes of research. We can dive into the imagined experience of being "then" and "there" asynchronously and remotely, as countless people have done before the pandemic and will continue to do. Moreover, we can choose to employ para-ethnographic means to learn from, collaborate with, and empower others who may bring their own experiences, memories, and insights to bear on our research subject and produce knowledge.31 I may add that we can also dedicate our efforts in this moment to using our own resources and networks to support, complement, and signal boost research being done by native scholars and other professionals in other parts of the world. There is much work that may be done remotely and should be done regardless. It is ultimately dependent upon us, not our geographical location or some mystical notion of “being there” at a physical fieldsite, whether our work is rigorous and valuable.

Field Notes

At the time of writing this piece, I am unable to enter Japan to begin my dissertation research fellowship, but I continue to conduct my digital ethnography remotely full-time from the desk in my parents' kitchen. I am virtually plugged-in to my online network of fieldsites at all times. On an average day, I check my email and my social media correspondence with research participants. I then follow up on any notifications I missed overnight that indicate new or continuing discussions within the online religious communities I study. I archive and annotate these webpages with my initial impressions for future reference. Sometime in the afternoon, I'll be in contact with a Shinto priest who is just starting her day on the other side of the country, whom I assist with managing the shrine Facebook group and drafting, translating, and posting shrine announcements across multiple social media platforms. Late at night, I attend ritual and cultural livestreams being broadcast from other time zones and continents.

This is taxing work. My neck and back ache from sitting at a desk or looking down at my phone. My eyes strain from hours of staring at a screen. My jaw locks in response to the emotionally-charged discussions I participate in. I am physically, mentally, and emotionally fatigued by being available 24/7. I think that many more people understand the demands of this kind of work through our shared experience of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even still, I encounter colleagues who wonder what it is exactly that I do all day and whether it is "enough" to consider myself an area scholar because I am able to do it outside of Japan. To be completely honest, it is more than enough. In fact, it is often too much. In response to the scrutiny of my peers, I overwork myself to prove that I am actively engaged and that my work is serious and rigorous. It is my hope that the pandemic will serve as a catalyst for our understanding that rigorous research is not dependent on one's geographical location (although the funding for said research often is) and for a communal reevaluation of how our current notions of rigor perpetuate harmful standards for researchers.32

Remote Research Is Valuable

The third and final fallacy of remote research, that it is not valuable on its own, must now be put to rest. By now, I have already suggested just how valuable research at a distance can be. Yet despite decades of solid arguments in digital anthropology against it, the notion that digital research is partial or supplemental—that is, inherently insufficient—persists. After their experience of other countries and cultures being rendered inaccessible for a variety of reasons—spatial, temporal, legal, etc.—in the twentieth century, the venerable anthropologists Margaret Mead and Rhoda Métraux created a manual specifically designed to help guide “the study of culture at a distance” through media including films and literature. However, in the tome’s introduction, Mead explicitly qualifies remote research as applicable “only when it is essential” and unsuitable for “theoretical purposes.”33

Postill suggests that such a position stems from the “anthropological aversion to thin descriptions.”34 But if the researcher is able to access the kind of insights into a research topic that they need through remote fieldwork, and if they treat it in the same methodical and ethical way as they do in-person fieldwork, there should be no reason that the results would be fundamentally inferior. Conducting research through primarily remote methods can yield a different perspective on an issue. We may use sources in more imaginative ways, focus on different aspects, and notice new patterns. Every part of this experience is valuable. Moreover, we conduct analysis at different speeds and depths depending on a number of factors, such as a topic’s relative significance the focus and scope of our research, uneven materials, space constraints, and editorial requirements. There is a place in our research for both thick and thin description.35 Granted, it is entirely possible to do “bad” remote research just as it is to do bad in-person research. The onus is on the researcher to produce thoughtful and meaningful work out of the methods and materials they choose.

Field Notes

It is not presumptuous to acknowledge that my digital and remote research is valuable. My methods are tailor-made to investigate emerging trends and answer questions that my field has not addressed in this way before. By focusing on transnational networks facilitated by the Internet that both center and de-center Japan as the locus of Shinto ritual practice, I am able to study the process of Shinto's globalization as it unfolds and interrogate notions of religious authenticity and authority that intersect with race and culture. My project has everything to do with Japan, but it is not geographically bound to the territorial borders of the Japanese state. This work demands online and remote ethnographic research, but it also requires institutional support.

We have all come to appreciate the very real costs of conducting remote research. Studying another region does not exempt us from living expenses wherever we are physically located. On top of that, there are technology costs (hardware, software, subscriptions), research assistant and participant compensation, and even travel costs on occasion. But remote research must also be valued as an analytical perspective and an area of technical expertise by hiring committees. More than once, colleagues have wondered aloud if I will be at all competitive on the job market due to the nature of my research. Prior to the pandemic, my decision to conduct transnational, digital ethnographic research was considered a personal choice and a risky gamble. If it paid off, I would be a cutting-edge contender; if it failed, no one would take me seriously as an area studies scholar. Now that remote research is not a choice made by few but a necessity for many, we need as a field to critically reexamine how we value and support this kind of scholarship.

The Impact of COVID-19 on the Global Academy

The many unanticipated consequences of the global pandemic have exposed a multitude of flaws in the infrastructure of academia. At the present moment, the task of reimagining remote research and an academy which supports this type of work is of critical importance to the wellbeing of the scholarly community, in particular our graduate students. We are entirely dependent on the support of grants and fellowships to conduct what is for many of us our first extended time in the field. These funds typically allow us to travel to archives and fieldsites, to purchase equipment, attend conferences, and participate in workshops. But even more fundamental, they support our day-to-day living expenses: food, rent, utilities, health insurance, childcare, and student loan payments.

What then are graduate students to do when funding packages do not allow for remote research? I will use myself as an example. Even prior to the pandemic, remote research—central to my project from the beginning—posed a problem for my funding prospects. Fellowship selection committees were puzzled by my proposals focusing on online religious communities. If I could do that work anywhere, why did I need funding? I was counseled by various mentors that I had to prove why I needed to be physically present in Japan to conduct my research in order to be competitive in any way. Digital and transnational scholarship are buzzwords these days, but the decisions made about what kind of research is rigorous and what projects are worth funding are still bound to physical and national units. I knew that getting my research funded by a prestigious organization was crucial if I had hopes of an academic career. So, I did what I had to do. Eventually, I successfully crafted a proposal that foregrounded classical anthropological research at religious sites and buried the communities that were at the heart of my work. I figured that I had resolved the problem.

In preparation for my fieldwork, I followed all the proper procedures. I filed in absentia at my university, hitting pause on my institutional funding. This meant that I needed to move out of subsidized graduate housing, put everything in storage, move from California back to New York, and rely on my parents' health insurance (I was lucky to be 25 at the time) until the summer of 2020 when I would move to Japan. I found an apartment and a roommate in Tokyo, and we signed a contract. Then COVID-19 hit, and international borders closed. At first, I was not too worried about my situation; I was well-positioned to continue the online research I had already started. I did everything I could to make sure I was ready to move when the restrictions lifted.

But as weeks of lockdown turned into months, I began to realize the immense financial cost to not being able to conduct in-person research in another country. I was paying storage fees in California and rent in Tokyo. I turned 26 and aged off of my parents' health insurance. One funding agency was incredibly flexible and generous; they had the ability to support my remote research. But as of writing this piece, that fellowship has ended. I cannot start the next one until I am physically present in Japan. I am effectively stranded. I barely have time to conduct my online research as I take whatever side jobs I can get and deplete my meager savings to pay the bills. And the kicker is, my position is much more fortunate than others. I am single, have no children, have some savings and marketable skills, and a place to live with family who support me. Meanwhile, colleagues in my cohort are going further into debt to try to make ends meet while they wait to begin their fellowships. They tell me that if the situation continues for a few months more, they will have to leave academia altogether in order to provide for their families.

It has become painfully clear that our livelihoods hang in the balance because of the academy's expectations regarding where and how scholars ought to conduct their research. However well-equipped we may be to conduct remote research, it is not viable if it is not valued in dollars and cents. If institutional attitudes toward remote research do not change significantly and soon, area studies as a whole is poised to lose an entire generation of young scholars unable to support themselves in their fieldwork years, save those who are independently wealthy and can afford to wait and work for free.

Conclusion

In this essay, I have attempted to demystify the history of remote research in anthropology and area studies and trace several prevalent misconceptions concerning the practice of research at a distance. I find that one of the powerful ideologies behind our anxieties over remote research is the notion that “being there” is fundamental to one’s work and professional identity. I have suggested that remote research has a significant history and offers new possibilities given recent technological developments. Remote research can be equally as rigorous and productive as in-person fieldwork, if in different ways.

Researchers have had to negotiate numerous personal and professional commitments and constraints long before the pandemic. The consequences of COVID-19 have only multiplied, exacerbated, and distributed issues many of us were already facing. What is different about this moment is that we all find ourselves (not just digital ethnographers and online researchers), at the same time, in a crucible, a crisis of methods and epistemologies—one which offers us the opportunity to reimagine what it means to be a researcher and to do scholarly research at a distance, both in our individual fields and as a scholarly community. Moreover, this period of great immobility has highlighted the privileges that many of us have taken for granted for too long. We must be careful to recognize that the solutions to the problems that currently stymie our research do not lie in overcoming the temporary obstacles to our movement, but in addressing the burdens that our expectation of mobility put on those who for a multiplicity of reasons cannot or do not choose to do so.

It is my hope that, having named and contextualized the misgivings we share about increased engagement with remote research, we may push past these anxieties and bring our considerable knowledge and diverse perspectives to bear on more critical questions: How exactly do we conduct remote research in our disciplines? How does remote research trouble what George Marcus calls “the aesthetics of practice and evaluation” that define our “disciplinary culture[s] of method and career-making?”36 How do we reconcile the necessities of remote research with our professional identities as area specialists deeply embedded in the languages, locations, and cultures we study? How should we go about training people in remote research methods? What role should remote research play in our work long-term? How do we change institutional structures and expectations so that scholars conducting remote research projects are recognized as members of the academic community, eligible for funding and other forms of support, and taken seriously on the job market?

We need to get comfortable with the fact that remote research will not simply go away once the pandemic has passed—nor should it. Where there is anxiety, there is opportunity for reflection, insight, and growth. If remote research, as it is now, presents an existential threat to area studies, it benefits us to articulate why. We need to clarify what area studies has to offer when those areas are off limits. Doing so will only make us more resilient in the face of future disruptions and better-equipped to respond to the problems of our times.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by support from the Social Science Research Council’s International Dissertation Research Fellowship, with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Bibliography

Abidin, Crystal and Gabriele De Seta. “Private Messages from the Field: Confessions on Digital Ethnography and Its Discomforts.” Journal of Digital Social Research 2, no. 1 (February 2020): 1–19.

Appadurai, Arjun. "Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy," Theory, Culture & Society 7, no. 2-3 (June 1990): 295-310.

— — —. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Asad, Talal, ed. Anthropology & the Colonial Encounter. London: Ithaca Press, 1973.

Boellstorff, Tom. Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Boellstorff, Tom, Bonnie Nardi, Celia Pearce, and T. L. Taylor. Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Cowan, Douglas. Cyberhenge: Modern Pagans on the Internet. London: Taylor & Francis, 2005.

de Seta, Gabriele. “Three Lies of Digital Ethnography.” Journal of Digital Social Research 2, no. 1 (February 2020): 77–97.

Faubion, James and George Marcus, eds. Fieldwork Is Not What It Used to Be: Learning Anthropology’s Method in a Time of Transition. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009.

Friedman, P. Kerim. “Armchair Anthropology in the Cyber Age?” Savage Minds: Notes and Queries in Anthropology, May 19, 2005. Accessed February 15, 2021. https://savageminds.org/2005/05/19/armchair-anthropology-in-the-cyber-age/.

Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books, 1973.

— — —. Works and Lives: The Anthropologist as Author. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988.

Gray, Patty. “Memory, Body, and the Online Researcher: Following Russian Street Demonstrations Via Social Media,” American Ethnologist 43, no. 3 (August 2016): 500-510.

Grieve, Gregory. Cyber Zen: Imagining Authentic Buddhist Identity, Community, and Practices in the Virtual World of Second Life. London: Routledge, 2016.

Günel, Gökçe, Saiba Varma, and Chika Watanabe, "A Manifesto for Patchwork Ethnography," Member Voices, Fieldsights (June 2020): n.p. Accessed February 15, 2021. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/a-manifesto-for-patchwork-ethnography.

Hannerz, Ulf. “Being There ... and There ... and There! Reflections on Multi-Site Ethnography.” Ethnography 4, no. 2 (June 2003): 201–16.

Hine, Christine. Ethnography for the Internet: Embedded, Embodied, Everyday. London: Bloomsbury, 2015.

Hjorth, Larissa, Heather Horst, Anne Galloway, and Genevieve Bell, eds. The Routledge Companion to Digital Ethnography. London: Routledge, 2017.

Holmes, Douglas and George Marcus. "Cultures of Expertise and the Management of Globalization: Toward the Re-Functioning of Ethnography." In Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics and Anthropological Problems, edited by Aihwa Ong and Stephen Collier. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2005.

— — —. "Collaboration Today and the Re-Imagination of the Classic Scene of Fieldwork Encounter." Collaborative Anthropologies 1 (2008): 81-101.

Kolluoglu-Kirli, Biray. “From Orientalism to Area Studies.” The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (Fall 2003): 93–111.

Kozinets, Robert. Netnography: Redefined. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2015.

Malinowski, Bronisław. Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. London: G. Routledge and Sons, 1922.

— — —. Myth in Primitive Psychology. London: Norton, 1926.

Marcus, George. “Ethnography In/Of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography,” Annual Review of Anthropology 24 (October 1995): 95-117.

— — —. Para-Sites: A Casebook Against Cynical Reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Mead, Margaret and Rhoda Metraux, eds. The Study of Culture at a Distance. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1952.

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. “Anti-Area Studies.” Communal/Plural 8, no. 1 (2000): 9-23.

Postil, John. "Remote Ethnography: Studying Culture from Afar.” In The Routledge Companion to Digital Ethnography, edited by Larissa Hjorth, Heather Horst, Ann Galloway, and Genevieve Bell, 61-69. London: Routledge, 2017.

Price, Devon. Laziness Does Not Exist: A Defense of the Exhausted, Exploited, and Overworked. New York: Atria Books, 2021.

Sera-Shriar, Efram. “What Is Armchair Anthropology? Observational Practices in 19th-Century British Human Sciences.” History of the Human Sciences 27, no. 2 (April 2014): 26–40.

Sloan, Luke and Anabel Quan-Haase, eds. The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2017.

Vangkilde, Kasper and Morten Rod. “Para-Ethnography 2.0: An Experiment with the Distribution of Perspective in Collaborative Fieldwork.” Collaborative Formation of Issues: The Research Network for Design Anthropology. Aarhus: The Research Network for Design Anthropology, 2015.

Endnotes

1 Bronisław Malinowski, Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea (London: G. Routledge and Sons, 1922).

2 Clifford Geertz, Works and Lives: The Anthropologist as Author (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), 1-24.

3 George Marcus, “Introduction: Notes toward an Ethnographic Memoir of Supervising Graduate Research through Anthropology’s Decades of Transformation,” in Fieldwork Is Not What It Used To Be: Learning Anthropology’s Method in a Time of Transition, ed. James Faubion and George Marcus (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009), 5.

4 Gabriele de Seta, “Three Lies of Digital Ethnography,” Journal of Digital Social Research 2, no. 1 (February 2020): 77-97, 80.

5 John Postill, “Remote Ethnography: Studying Culture from Afar,” in The Routledge Companion to Digital Ethnography, ed. Larissa Hjorth, Heather Horst, Anne Galloway, and Genevieve Bell (New York: Routledge, 2017), 61-69.

6 Efram Sera-Shriar, “What is armchair anthropology? Observational practices in 19th-century British human sciences,” History of the Human Sciences 27, no. 2 (April 2014): 26-40.

7 Bronisław Malinowski, Myth in Primitive Psychology (London: Norton, 1926), 71.

8 Malinowski, Myth in Primitive Psychology, 71-73.

9 Clifford Geertz, Works and Lives, 16.

10 Biray Kolluoglu-Kirli, “From Orientalism to Area Studies,” The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (Fall 2003): 93–111.

11 P. Kerim Friedman, “Armchair Anthropology in the Cyber Age?” Savage Minds: Notes and Queries in Anthropology, May 19, 2005, accessed February 15, 2021, https://savageminds.org/2005/05/19/armchair-anthropology-in-the-cyber-age/.

12 Talal Asad, ed., Anthropology & the Colonial Encounter (London: Ithaca Press, 1973), 16-18.

13 Sera-Shriar, “What is Armchair Anthropology?,” 33-34.

14 Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “Anti-Area Studies,” Communal/Plural 8, no. 1 (2000): 9-23, 14.

15 For examples, see Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996); James Faubion and George Marcus, eds., Fieldwork Is Not What It Used to Be: Learning Anthropology’s Method in a Time of Transition (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009).

16 Sera-Shriar, “What is Armchair Anthropology?,” 27.

17 Postill, “Remote Ethnography,” 63.

18 Gökçe Günel, Saiba Varma, and Chika Watanabe, "A Manifesto for Patchwork Ethnography," Member Voices, Fieldsights (June 2020): n.p. Accessed February 15, 2021. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/a-manifesto-for-patchwork-ethnography

19 Arjun Appadurai, “Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy,” Theory, Culture & Society 7, no. 2-3 (June 1990): 295-310.

20 George Marcus, “Ethnography In/Of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography,” Annual Review of Anthropology 24 (October 1995): 95-117.

21 For examples, see Tom Boellstorff, Bonnie Nardi, Celia Pearce, and T. L. Taylor, Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012); Christine Hine, Ethnography for the Internet: Embedded, Embodied, Everyday (London: Bloomsbury, 2015); Robert Kozinets, Netnography: Redefined, 2nd ed., (London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2015); Larissa Hjorth, Heather Horst, Anne Galloway, and Genevieve Bell, eds., The Routledge Companion to Digital Ethnography (London: Routledge, 2017); Luke Sloan and Anabel Quan-Haase, eds., The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods (London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2017).

22 Kaitlyn Ugoretz, “Academic Talk | ‘Hacking Fieldnotes: Using Scrible to Qualitatively Study the Internet’ AAS 2021,” YouTube, March 2, 2021, https://youtu.be/aYI1qmVZ5UM.

23 Ulf Hannerz, “Being there… and there… and there! Reflections on multi-site ethnography,” Ethnography 4, no. 2 (June 2003): 201-216, 202.

24 Postill, “Remote Ethnography,” 66.

25 For examples, see Patty Gray, “Memory, Body, and the Online Researcher: Following Russian Street Demonstrations via Social Media,” American Ethnologist 43, no. 3 (August 2016): 500-510; Postil, “Remote Ethnography”; Crystal Abidin and Gabriel de Seta, “Private Messages from the Field: Confessions on Digital Ethnography and Its Discomforts,” Journal of Digital Social Research 2, no. 1 (February 2020): 1–19; de Seta, “Three Lies of Digital Ethnography,” 93.

26 Gray, “Memory, Body and the Online Researcher,” 502.

27 For examples, see Douglas Cowan, Cyberhenge: Modern Pagans on the Internet (London: Taylor & Francis, 2005); Tom Boellstorff, Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008); Kozinets, Netnography: Redefined; Hine, Ethnography for the Internet; Gregory Grieve, Cyber Zen: Imagining Authentic Buddhist Identity, Community, and Practices in the Virtual World of Second Life (London: Routledge, 2016).

28 Gray, “Memory, Body and the Online Researcher,” 502.

29 de Seta, “Three Lies of Digital Anthropology,” 88.

30 Postill, “Remote Ethnography,” 66.

31 See George Marcus, Para-Sites: A Casebook Against Cynical Reason (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000); Douglas Holmes and George Marcus, "Cultures of Expertise and the Management of Globalization: Toward the Re-Functioning of Ethnography," in Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics and Anthropological Problems, ed. Aihwa Ong and Stephen Collier (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2005); Douglas Holmes and George Marcus, "Collaboration Today and the Re-Imagination of the Classic Scene of Fieldwork Encounter," Collaborative Anthropologies 1 (2008): 81-101; Kasper Vangkilde and Morten Rod, “Para-Ethnography 2.0: An Experiment with the Distribution of Perspective in Collaborative Fieldwork,” Collaborative Formation of Issues: The Research Network for Design Anthropology (Aarhus: The Research Network for Design Anthropology, 2015).

32 Devon Prince, Laziness Does Not Exist: A Defense of the Exhausted, Exploited, and Overworked (New York: Atria Books, 2021), 14.

33 Margaret Mead and Rhoda Métraux, eds., The Study of Culture at a Distance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953), 3.

34 Postill, “Remote Ethnography,” 66.

35 Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973).

36 George Marcus, “Introduction,” 1.