The Digital, The Local and The Mundane: Three Areas of Potential Change for Research on Asia

References | Author Bio | ![]() Download the PDF

Download the PDF

Keywords: digital, early modern, Japan, pedagogy, self-ethnography, performative, blended learning, blended research

The Covid-19 pandemic has been a game-changer for academic research because it has affected all of its aspects, starting from the “where,” which influences the “what” and the “how.” Increasing dependence on online access means that the researcher themself needs to be astute in digital technology and proactive in orchestrating their own online presence. Additionally, the shift to working from home also affects researchers—the main advantage of their affiliation to an academic institution is now the access to online databases. On the other hand, when going beyond reference works, the “what” of research is inversely affected—direct access to remote sources can no longer be taken for granted. The same goes for the “how” of research—exhaustive research of a topic is arguably impossible, favoring eclectic studies on smaller topics closer to home.

Given these changes, I would like to suggest a few possibilities for updating the “where,” the “what,” and the “how” of research on the Asia Pacific region. I will illustrate these possibilities with some of my own strategies developed or reinforced during the pandemic, as a historian of the art and culture of early modern Japan. Three dimensions of the changes guide my suggestions: the digital, the local and the mundane.

Digital Goes Mainstream

While geographic mobility has been limited by the pandemic, a silver lining is that the resulting situation has leveled access to digitized primary sources.1 I fondly remember my experience of consulting the many volumes of Nihon Kokugo Daijiten日本国語大辞典 [Great Dictionary of the Japanese Language] and the new series of Shin Nihon Koten Bungaku Zenshu 新日本古典文学全集 [Collection of Premodern Japanese Classics] on the shelves of the History of Literature research room in Kanazawa University. However, those same works, along with many other such voluminous series, are now available digitally from JapanKnowledge through the CrossAsia service offered by Berlin State Library. Moreover, leading institutions such as the National Diet Library and the Art Research Center at Ritsumeikan University are making an increasing number of visual and bibliographic sources available online.2 Thanks to international standards such as IIIF and Linked Open Data, it is now possible to display images from different databases as well as from normal websites within one interface. Searching by image or by keyword can lead to unexpected results, and this will be only accelerated by the implementation of advancing AI algorithms as it has on search engines like Google.

The present challenge is to diversify the format of artifact viewers. In their current shape, image viewers are implicitly modeled after an iconographic approach to the history of art, epitomized by the former practice of showing two projector slides side by side in art history courses. The field of art history is moving beyond such approaches to stress the embodied experience enabled by the artifact. In this sense, there is plenty of potential in applying 3D visualization and VR techniques to reconstructing the life world of which the artifacts were once a part.

However, this leveled access does not necessarily translate to the democratization of access. Paywalls are a lingering issue for research databases such as JSTOR as well as reference databases such as CrossAsia. Research funding needs to address the growing importance of digital research by allocating funds specifically for database access. In countries such as Romania, the Japan Foundation has been providing book donations to Japanese studies departments. Equally, if not more mutually beneficial for such burgeoning research centers would be financial assistance in accessing major reference databases such as JapanKnowledge.

Alongside access to primary sources, online access to research results also needs to be prioritized. The pandemic has accelerated the mainstreaming of open access knowledge.3 This should reduce the stigma of working with sources accessed only online, which still lingers in the field of art history. This does not diminish the importance of acquiring direct knowledge of the material properties of the artifacts under study, and I will elaborate more on solutions to this in the fourth section of this paper. What it does mean, though, is that the importance of being proficient in digital research skills has increased exponentially, becoming at least as crucial as analog research skills. Again, funding schemes need to adapt to this necessity.4

The increasing centrality of the digital also applies to the researcher’s role as a communicator. The pandemic has exposed the preexisting fact that a successful academic career also hinges upon enhanced digital visibility. More than ever, researchers need to put themselves and their work in the digital medium. When doing so, it is no longer sufficient to replicate analog forms of academic visibility. The increased possibilities of the digital medium contain the potential to rethink our “scholarly apparatus” through, for example, “small-gauge” scholarship disseminated on blogs and podcasts.5 The digital also encourages us to be open-sourced about our research processes.6

For my part, the pandemic has made me reconsider the relevance of self-ethnography. As a scholar of Japonisme, I am interested in the inflections of Japanese culture and media in other cultures. I have recently been inspired by the proliferation of art memes on social media, especially Instagram, which was accelerated by the pandemic. It is not only a visual but also a performative phenomenon: during 2020, the act of recreating classic artworks by dressing up with household objects went viral. For example, the hashtag #betweenartandquarantine has been used more than fifty thousand times. The popularity of artwork impersonation stems arguably from its invitation to participatory responses to works of art at a time when physical access to the artworks is temporarily restricted.

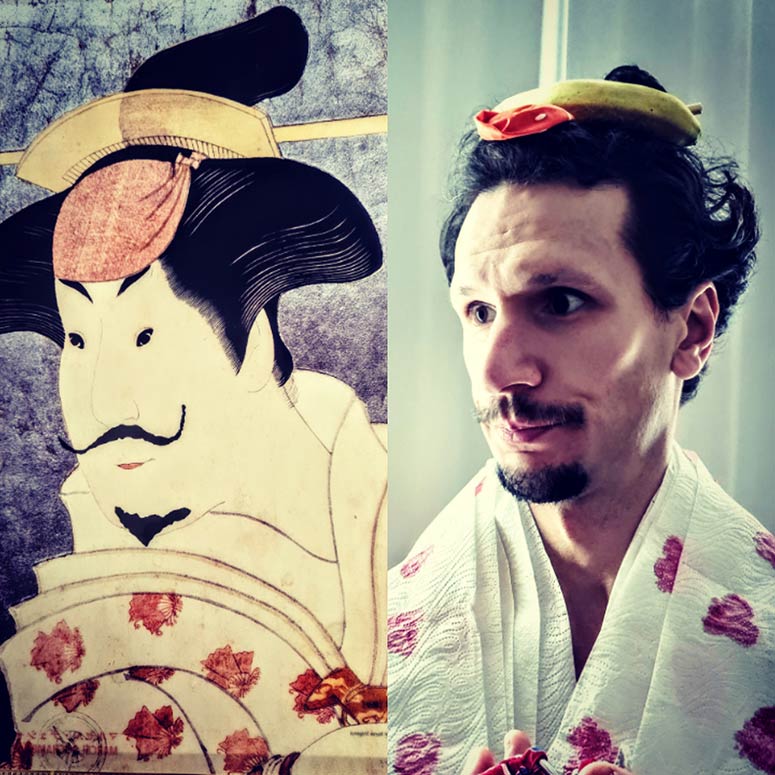

I chose to take part in this phenomenon by impersonating a uniquely multilayered image from early modern Japan and posting it on my Instagram account (see fig. 1). The initial state of this image is a lavish woodblock print with mica and bright colors, showing the profile of an obscure kabuki actor who specialized in female roles (onnagata 女形). It was an instant hit in the meteoric career of Sharaku, who was only active during the years 1794 to 1795. His popularity increased among Western collectors and scholars, culminating in a volume dedicated to him by the German scholar Julius Kurth.7 Sharaku’s style was unapologetically realistic to the extent that the illusion of femininity aimed at by female impersonators is dispelled. This was one of the reasons why I chose to impersonate one of Sharaku’s images: it is technically less demanding because the conceit of a man impersonating a woman is already highlighted in the initial image. Another reason for choosing this particular image was its inclusion in a Japanese addendum to a retrospective exhibition of Marcel Duchamp at Tokyo National Museum in 2018. As a souvenir, a file folder was produced with a mustache superimposed on Sharaku’s initial image, an homage to Duchamp’s readymade L.H.O.O.Q., which consisted of a postcard of the Mona Lisa on which Duchamp drew a moustache, goatee and the subversive initials.8

For the impersonation, I grew out my facial hair, water colored sheets of toilet paper to simulate the layers of the kimono, used a balloon to simulate the sash that covered the shaved area of a man’s head, and used a banana to imitate the comb. The process may be dismissed as irrelevant to actual scholarship, but the more than two hours needed to produce the shot provided plenty of food for thought: I now understand better the challenges of donning a multi-layered robe, as well as the specific framing choices made by the artist. There is also multilayering in terms of gender: I impersonate a man impersonating a woman who is again masculinized by facial hair. In terms of ethnicity, the interpretive effort of a non-Japanese impersonating a Japanese man parallels the interpretive effort of a modern non-Japanese researching early modern Japanese visual culture.

Impersonation and parody are certainly not new phenomena, and three distinct strategies overlap in this image: the first is the performative impersonation of the feminine character by the actor; the second, Duchamp’s gesture of defacing a celebrated work of art, which has become one of the strategies for producing shock value in contemporary art; and the third, impersonation as practiced by performance artists such as Cindy Sherman and Yasumasa Morimura. What is significant about that last strategy is that it is now democratized: anybody can achieve it and instantly post it to a worldwide audience. The iconic nature of images is amplified by social media. DIY culture intersects with high art, leveling previous hierarchies.

The paradigm of appreciating art is thus becoming an interactive experience. Some museums are acknowledging this, such as the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum with its online digital database contest that openly called for modifications to the artifacts in their collections. Many of the winning entries featured the direct involvement of their authors. The takeaway for researchers is that the digital medium offers new possibilities of doing and acting out research through performative involvement, which has the potential of transforming research practices as well as increasing the impact of research on the wider society.

The Potential of Local Networks

The merging of global and local dynamics is often described with the term “glocal,” which originated in the late ‘80s Japanese business speak term dochakuka.9 In a connected world, local elements are those that can make a difference. This is especially true in a pandemic situation in which digital nomads are turning into digital residents. Again, the switch to digital learning and work meeting platforms means increased access for researchers outside Asia to, for instance, research seminars at local Japanese universities.10 The digital medium enables a collaborative research environment where all participants, irrespective of location, can, for example, read and annotate an ancient text together by sharing screens.11

Another relevant response to the restriction of travel is to reframe one’s research to one’s surrounding environment. This requires a skill set not provided by area studies, a discipline that focuses on a distant object of inquiry. Researching local phenomena will also be incentivized by increased pressure for university communities to connect with the societal needs of non-academic communities.12 At a time when spontaneous networking has become almost impossible due to restricted travel and the characteristics of the online conferencing medium, this reorientation towards local actors holds the potential for new research partnerships.13

In terms of research topics, I expect there will be a boom in studies of Orientalism and Japonisme, as researchers start to look for elements in their immediate surroundings that contain cultural elements of Asian origin. This, however, needs to be accompanied by a willingness to step out of the national boundaries of area studies and engage with the particular cultural context of one’s home, in which the Asian origin of cultural elements might not be necessarily of prime relevance.14 For example, in Romania, my parents’ generation perceived premodern Japan through the mediation of a British novel—James Clavell’s Shōgun—and its US-produced TV adaptation. However, as a researcher it is difficult to apply for funding from Japan to study the influence of such ideas about Japan in Central and Eastern Europe. Although Japanese studies in this geographical area is identified as being of strategic interest by the Japan Foundation, funding is restricted to topics with direct Japanese geographical or ethnic origin, the implicit assumption being that only topics with an authentic Japanese pedigree are worth studying. However, if research on Asia is to maintain relevance, it needs to stop insisting on the intrinsic value of studying exceptionalized “Asian”’ topics. Instead, we need to include within our research scope phenomena characterized by hybridity and flow at work both in the contemporary world and in the past.

While digital connections have maintained and intensified the flow of information and ideas between distant localities, another mode of informational infrastructure often taken for granted in maintaining local-to-local connections is the postal service. Postal infrastructure predates extensive air travel and digital connections, and it is particularly good at maintaining a physical connection through the mediation of objects: gifts, merchandise, letters, and postcards. This infrastructure can be enlisted for research purposes. The cost of buying and posting research materials is minute compared to that of traveling for direct consultation. The money saved from travel costs can be redeployed for the acquisition of primary and secondary sources. This has the additional incentive of reducing the carbon footprint of fieldwork—an objective which is already being embraced by large corporations.15

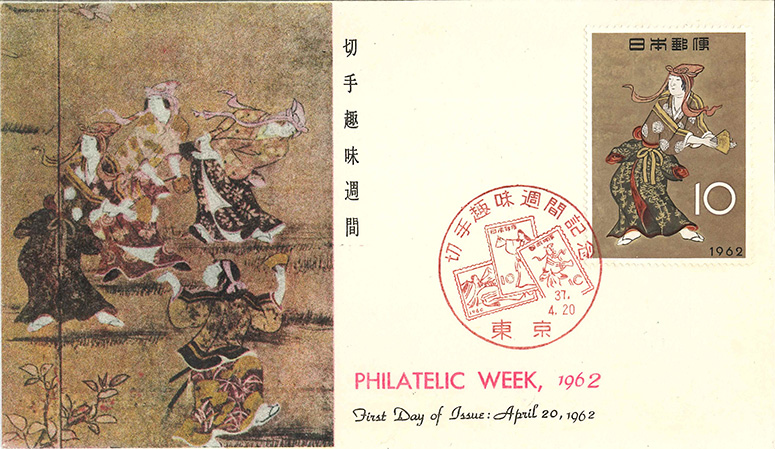

Granted, not all primary sources are amenable to postal transfer. This is where we need to be flexible in the “what” of our research. Personally, the pandemic has made me reassess the potential of stamps and postcards for studying the visual and material culture of Japan.16 I took another look at a 1962 art-themed stamp I had bought on Amazon from a Tokyo collector (see fig. 2). It features a detail of a female dancer from an early-seventeenth-century folding screen designated as National Treasure: “Merrymaking Under the Cherry Blossoms” by Kano Naganobu. For a First Day Cover edition, a custom envelope was prepared, featuring a printed reproduction of a photograph of the corresponding detail from the original screen. The stamp was then pasted onto the envelope, and a cancellation was impressed in red ink with a custom handstamp showing the outline of the same dancer. The silhouette of the same dancer was then impressed in red ink with a custom-produced stamp. This material assembly problematizes two main issues: on the one hand, the mechanisms of art canon formation and perpetuation as they intersected with the institutional objectives of the Japan Post occurred at a time of enhanced national sentiment. Another issue is the often-undiscussed material dimension of these phenomena: the practice of stamp collecting involved complex processes of reproduction of works of art that complicate ideas of copy and original. The latter is particularly relevant in the context of the East Asian tradition of copying. Such collector’s items encapsulate the overlapping materiality of printed media in contemporary Japan, instigate fresh views on the initial materiality of the source image in early modern Japan, and prefigure the interplay between authenticity and simulation in the digital age.

The example above exposes another potential practice for all researchers during the pandemic: that of reviewing and consolidating previously gathered research material. All researchers have folders with unfinished article ideas, or book projects that are only assemblies of ideas and sources on a given theme. This is the time to go back to those folders and craft them into compelling studies. This opportunity to reflect on previously gathered sources can be channeled towards more synthetic and critically aware studies. This is especially the case in early modern Japanese studies, where comparatively few are methodologically adventurous.

Paradoxically, while it seems that restricted access hinders comprehensive studies, it can actually encourage a process analogous to the defragmentation of memory drives on a computer: sorting, grouping, consolidating material already archived. This does not have to be in established formats: for example, a recent report lists the “embedding of preprints in publication workflows ” as one the strategies for a sustainable model of open science.17 Another possible format is that of the “reading notes” proposed by Carla Nappi.18 And at Kyoto University, Björn-Ole Kamm is investigating the potential of Live-action role-play (LARP) for educational and research methodologies.19

Mundane Authenticity

There is a deep, unspoken assumption that the validity of research in art and archaeology rests upon authenticity. By this I mean that the researcher is expected to focus their attention on the actual objects from the time and place under their scrutiny. Replicas and reproductions, whether analogue or digital, are frowned upon—the emphasis is still on “primary” sources with a corresponding pedigree. But since Latour deconstructed the visual practices of science, we are much more aware of the subjective and narrative aspects of all research.20

When I was dressing up as one of Sharaku’s subjects, my expertise in the history of Japanese art might have made my reconstruction more accurate, but not more authentic. And yet, through impersonation I came to better understand the sartorial culture of the period and the specific choices made by Sharaku in the image. Indeed, the pandemic has given us an increased historical sensitivity: our material culture and knowledge-making practices cannot be taken for granted anymore. This sensitivity can be applied to study the past, just as we now watch video materials shot before Coronavirus times and wonder at the physical closeness of protagonists. While historians are already attuned to this, it makes it easier to appeal to a shared defamiliarizing experience when drafting our research papers for a wider audience.

There remains, of course, a lack of direct contact with primary sources, which is especially crucial in a discipline such as art history. The memory and knowledge of the material properties of the objects central to art historical inquiry should be actively maintained. One method I found useful originated in the swift transition of university courses to online teaching due to the pandemic. I was scheduled to teach a class on the material culture of entertainment media in seventeenth-century Japan. I had planned to bring certain objects to class and to encourage the students to talk about their materials, function and meaning. Most were not original objects: a Russian Matrioshka doll, a dinosaur-shaped tea bag, a coaster with a print of an oil painting of Paris. But they raised the same questions posed by seventeenth-century Japanese sources: the creation process and the material properties of the objects, or the status of manuscript culture versus print culture. When the course had to switch fully online, I thought of our shared experience: as we avoided public spaces and contact with other people, our proximity and use of objects in our homes increased. I took this as an opportunity to encourage critical thoughts on the very objects that my students found themselves in confinement with. I asked students to choose an object from their home whose characteristics paralleled those of each week’s lecture theme, write two hundred words about it, and submit it along with a photo.

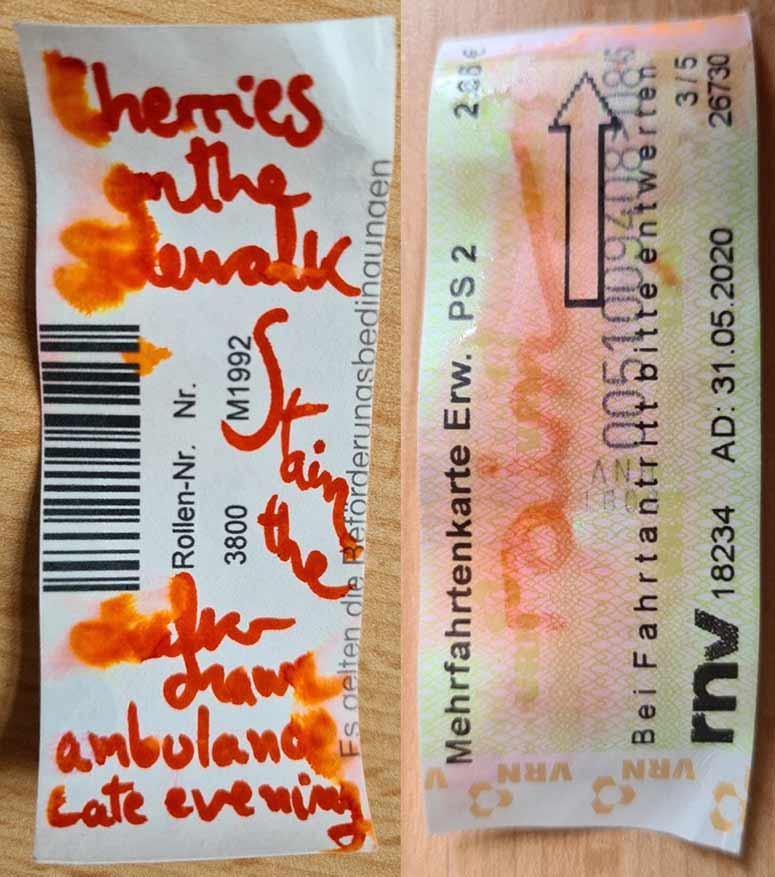

Their responses were enthusiastic, and I also joined in with my own chosen objects. Some of these were not just found, but actively produced: for example, for the session on poetry making in late-seventeenth-century Japan, I wrote a poem on a tram ticket with a water-soluble ink, intentionally bled out (see fig. 3). This recalled the juice of cherries oozing into children’s chalk drawings on an alley floor, as well as the ongoing killings of African -Americans in the US and racist crimes everywhere. The latter is also evoked by the ambulance, one of the few ways out of our confined lives in the cages of our homes. The last word of the poem, “rain,” did not fit with the rest, but a knowledgeable reader would look for the seventeenth syllable and find it on verso, bled out to blend in with the company logos.

At the end of the course, students chose their favorite “object journals” that we edited into an “objectzine"—material evidence of an otherwise virtual learning experience. While this is an example of blended learning, we can also imagine blended research that melds online resources with insights gleaned from mundane sources available locally. In this sense, the need to structure my material more thoroughly and ahead of time for online delivery resulted in a “repository of reusable educational content” that can also be reused as research output.21 The material was so rich and the organization of the course so persuasive, that I can see the seed of a monograph project in it. So thinking with mundane materials such as postcards or bus tickets can result in a study on broader themes that bypass the exceptionalism of “Asian” topics.

Conclusion

To sum up, this is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reassess and transform our research practices. The “what,” the “where,” and the “how” of research were affected along three potential-filled factors: the digital, the local, and the mundane. All these aspects impact another important parameter of research: that of the “who.” In a digitally connected world, anyone can post and publish, eroding the rhetorical authority of the academic researcher. Rather, academic researchers need to engage with current knowledge-making practices with a more collaborative and open-access mindset. This also means connecting more to colleagues worldwide and participating in more collaborative platforms and forms of knowledge-making.22 In this process, researchers also need to be more directly and openly involved in the framing and shaping of their objects of inquiry, whether it is “Asia,” “Japan,” or “religion.” In this sense, we need to take seriously the call within performance studies for performance-as-research by involving our bodies and biographies in the research process.23

This necessity for a change of perspective also applies to funding schemes that need to adjust their concept of a researcher as on the one hand a non-biased and non-privileged actor, and on the other hand someone who needs to travel physically to do research. Rather, research funding can be directed toward enabling digital infrastructure for sharing sources and research results outside national boundaries and logocentric publication media. For example, German funds could support researchers in Japan that collect data then shared online with researchers based at German universities. Moreover, we should not fence in our topics to deal only with “authentic” artifacts: they can include objects from everyday life, discussed in the same terms and reflecting back on the understanding of the “authentic” artifacts. The aim is to melt the dichotomy between mundane and “authentic” objects that relies on the assumption of spatial and temporal unity of the object of study. More than ever, our research should reflect the fluid and hybrid nature of our identities and circumstances.

Acknowledgments

This paper emerged from research undertaken within the Collaborative Research Centre 933 “Material Text Cultures. Materiality and Presence of Writing in Non-Typographic Societies.” The CRC 933 is financed by the German Research Foundation (DFG). I am grateful to Alex Mustăţea for constructive comments on an earlier draft.

Bibliography

Barclay, Paul D. East Asia Image Collection. Easton: Lafayette College. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://dss.lafayette.edu/collections/east-asia-image-collection/

Cipra, Barry. “Duchamp and Poincaré Renew an Old Acquaintance.” Science 286, no. 5445 (November 26, 1999): 1668-69. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1668.

Fosci, Mattia, Lucia Loffreda, Andrea Chiarelli, Dan King, Rob Johnson, Ian Carter, Mark Hochman. Emerging from Uncertainty: International Perspectives on the Impact of COVID-19 on University Research. London: Springer Nature, November 2020. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.13130063.

Gomez Recio, Silvia and Chiara Colella. The World of Higher Education after COVID-19. Brussels: Yerun, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.yerun.eu/2020/07/yerun-publishes-reflection-paper-on-the-world-higher-education-after-covid-19.

Holmberg, Ryan. The Translator without Talent. Richmond: Bubbles Zine Publications, 2020.

Jones, Simon. “The Courage of Complementary.” Practice as Research in Performance National Conference (September 2003). Accessed May 10, 2021. http://www.bris.ac.uk/parip/jones.htm.

Kamm, Bjorn Ole. Transcultural Learning through Simulated Co-Presence: How to Realize Other Cultures and Life-Worlds. Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Kaken number 19KT0028. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://kaken.nii.ac.jp/grant/KAKENHI-PROJECT-19KT0028/.

Kredell, Bernard. “Small-Gauge Scholarship: An Introduction.” Mediapolis 3, no. 1 (2016). Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.mediapolisjournal.com/2016/06/small-gauge-scholarship-introduction/.

Kurth, Julius. Sharaku. München: Piper, 1910.

Latour, Bruno. “Drawing Things Together.” In Representation in Scientific Practice, eds. Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar, 19–68. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990.

Martin, Drew and Arch G. Woodside. “Dochakuka.” Journal of Global Marketing 21.1 (2008): 19–32. doi: 10.1300/J042v21n01_03.

Nappi, Carla. “Reading Notes: The Intertwining: The Chiasm.” Carla Nappi’s Center for Historical Pataphysics. Posted summer 2015. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://carlanappi.com/reading-notes-the-intertwining-the-chiasm/.

National Diet Library Staff. “«Toshokan kankei no kenri seigen kitei no minaoshi (dejitaru nettowāku taiō) ni kansuru chūkan matome» e no pabburikku komento no jisshi kekka ga kōhyō sareru 「図書館関係の権利制限規定の見直し(デジタル・ネットワーク対応)に関 する中間まとめ」へのパブリックコメントの実施結果が公表される.” Current Awareness Portal. January 26, 2021. https://current.ndl.go.jp/node/43085.

Peycam, Philippe. “Imagining the University in the Post-COVID World.” IIAS Newsletter 88 (Spring 2021), 3. Accessed March 23, 2021. https://www.iias.asia/the-newsletter/article/imagining-university-post-covid-world.

Roudometof, Victor. Glocalization: A Critical Introduction. London: Routledge, 2016.

Wade, Belinda and Saphira Rekker. “Research Can (and should) Support Corporate Decarbonization.” Nature Climate Change 10 (December 2020), 104–65. doi: 10.1038/s41558-020-00936-0.

Endnotes

1 Mattia Fosci et al., “The Impact of COVID-19 on Researchers,” in Emerging from Uncertainty: International Perspectives on the Impact of COVID-19 on University Research, London: Springer Nature, November 2020), 6.

2 In December 2020, the Council for Cultural Affairs (文化審議会) of the Agency for Cultural Affairs (文化庁) in Japan invited public comments to its Interim Report of the Review of the Regulations on Library Rights Restrictions. The majority of the comments stressed the need for greater online access to digitized resources. For an overview of the comments and the final report see National Diet Library Staff. «Toshokan kankei no kenri seigen kitei no minaoshi (dejitaru nettowāku taiō) ni kansuru chūkan matome» e no pabburikku komento no jisshi kekka ga kōhyō sareru「図書館関係の権利制限規定の見直し(デジタル・ネットワーク対応)に関する中間まとめ」へのパブリックコメントの実施結果が公表される [Announcement of Public Comments on Review of Library-Related Rights Restrictions (Digital Network Support) Interim Summary] Current Awareness Portal. January 26, 2021. https://current.ndl.go.jp/node/43085.

3 Silvia Gomez Recio and Chiara Colella, The World of Higher Education after COVID-19 (Brussels: Yerun, 2020), 33; Mattia Fosci et al., “Ensuring Access to Research Information during the Pandemic,” in Emerging, 15-16; Mattia Fosci et al., “Conclusions,” in Emerging, 37.

4 Mattia Fosci et al., “Doing Research during the Pandemic,” in Emerging, 12; Mattia Fosci et al., “Research Collaborations,” in Emerging, 8.

5 Bernard Kredell, “Small-Gauge Scholarship: An Introduction,” Mediapolis 3, no. 1 (2016), accessed January 6, 2021, https://www.mediapolisjournal.com/2016/06/small-gauge-scholarship-introduction/.

6 A recent example of a publication that exposes the research process is a manga researcher’s compilation of Instagram posts on his research in Tokyo. See Ryan Holmberg, The Translator Without Talent (Richmond: Bubbles Zine Publications, 2020).

7 Julius Kurth, Sharaku (München: Piper, 1910).

8 The spelling of the initials is homophonous with the words “elle a chaud au cul”, which would roughly translate as “she has a hot ass." It has been convincingly argued by Rhonda Roland Shearer that Duchamp superimposed his own face over that of Mona Lisa, adding another layer to the image. See Barry Cipra, “Duchamp and Poincaré Renew an Old Acquaintance,” Science 286, no. 5445 (November 26, 1999): 1668-69. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1668.

9 Victor Roudometof, Glocalization: A Critical Introduction (London: Routledge, 2016), 2-3; Drew Martin and Arch G. Woodside, “Dochakuka,” Journal of Global Marketing 21.1 (2008): 19-32. doi: 10.1300/J042v21n01_03.

10 Mattia Fosci et al., “Research Collaborations,” in Emerging, 6.

11 Gomez Recio and Colella, The World of Higher Education, 28, 33.

12 Gomez Recio and Colella, The World of Higher Education, 29.

13 Mattia Fosci et al., “Research Collaborations,” in Emerging, 2.

14 On the need for interdisciplinarity see Gomez Recio and Colella, The World of Higher Education, 33.

15 Belinda Wade and Saphira Rekker, “Research Can (and Should) Support Corporate Decarbonization,” Nature Climate Change 10 (December 2020): 1064–65, doi: 10.1038/s41558-020-00936-0.

16 An inspiring example of an online database featuring such primary sources is Paul D. Barclay, East Asia Image Collection (Easton: Lafayette College), accessed May 10, 2021, http://digital.lafayette.edu/collections/eastasia.

17 Mattia Fosci et al., “Ensuring Access to Research Information during the Pandemic,” in Emerging, 16, 20, 38.

18 Carla Nappi, “Reading Notes: The Intertwining: The Chiasm,” Carla Nappi’s Center for Historical Pataphysics, posted Summer 2015, accessed May 10, 2021, https://carlanappi.com/reading-notes-the-intertwining-the-chiasm/.

19 As part of the research project Transcultural Learning through Simulated Co-Presence: How to Realize Other Cultures and Life-Worlds, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Kaken number 19KT0028, accessed May 10, 2021, https://kaken.nii.ac.jp/grant/KAKENHI-PROJECT-19KT0028/.

20 Bruno Latour, “Drawing Things Together,” in Representation in Scientific Practice, eds. Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990), 19-68.

21 Gomez Recio and Colella, The World of Higher Education, 40.

22 The same suggestion is made by Philippe Peycam, “Imagining the University in the Post-COVID World,” IIAS Newsletter 88 (Spring 2021), 3, accessed March 23, 2021, https://www.iias.asia/the-newsletter/article/imagining-university-post-covid-world.

23 Simon Jones, “The Courage of Complementary,” Practice as Research in Performance National Conference (September 2003), accessed May 10, 2021, http://www.bris.ac.uk/parip/jones.htm.