“It Is Good to Have Something Different”: Mutual Fashion Adaptation in the Context of Chinese Migration to Mozambique

REFERENCES | AUTHOR BIO | ![]() Download the PDF

Download the PDF

Keywords: China, Mozambique, fashion, adaptation, soft power, China-Africa relations, globalization

Introduction

Strolling along the orange dirt roads of her Northern Maputo suburb, Nadia1 is quite a sight to behold. Together with skinny jeans, a black faux leather handbag, and her signature Afro hairdo, she wears a long-sleeved bright red top, which is tight-fitting and of a thick synthetic fabric. Affixed to its little stand-up collar there are two nicely contrasting black silk knots holding together a subtle cut-out running diagonally across the right side of Nadia’s chest (see figure 1). Her top is reminiscent of a qipao, a style of Chinese dress that became popular in 1920s Shanghai. Having previously witnessed the former fashion shop employee describing Chinese fashion as a “quick thing” (coisa rapida), which “breaks in two days,” I curiously address her new outfit. Nadia, who was born and raised in Maputo, replies: “Yeah, Chinese style, it’s good to have something different, you know?” The top was actually a dress, which she had bought in South Africa. As her mother found the dress too short, she just took up the hem to wear it as a top. Going out in the evening, she receives many compliments from her girlfriends, who all want to know where she bought that smart new top.

Strolling along the orange dirt roads of her Northern Maputo suburb, Nadia1 is quite a sight to behold. Together with skinny jeans, a black faux leather handbag, and her signature Afro hairdo, she wears a long-sleeved bright red top, which is tight-fitting and of a thick synthetic fabric. Affixed to its little stand-up collar there are two nicely contrasting black silk knots holding together a subtle cut-out running diagonally across the right side of Nadia’s chest (see figure 1). Her top is reminiscent of a qipao, a style of Chinese dress that became popular in 1920s Shanghai. Having previously witnessed the former fashion shop employee describing Chinese fashion as a “quick thing” (coisa rapida), which “breaks in two days,” I curiously address her new outfit. Nadia, who was born and raised in Maputo, replies: “Yeah, Chinese style, it’s good to have something different, you know?” The top was actually a dress, which she had bought in South Africa. As her mother found the dress too short, she just took up the hem to wear it as a top. Going out in the evening, she receives many compliments from her girlfriends, who all want to know where she bought that smart new top.

At a fancy seaside restaurant in the southern part of Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, Xiwen uses her smartphone to show me pictures of work events she has attended for her employer, a large Chinese construction company. In most of the pictures she is wearing elegant mid-length dresses made of colorful cotton fabrics, which are known as “capulanas” in Mozambique. In a lively mix of Chinese and Portuguese, the administrative secretary from Zhejiang province in south-eastern China, who has been living in Maputo for two years, tells me about the small hidden tailor shop one of the capulana sellers recommended to her. She always goes to this tailor “because he knows me and my wishes.” Pointing at a geometrically patterned sleeveless dress with a full skirt (see figure 2), she explains that to be able to wear the dresses at work, she usually picks knee-covering designs and fabrics which are “not too typically African,” implying rather muted colors and patterns that are neither too bold nor too figurative. She also intends to wear her capulana dresses after her return to China at the end of this year. Asked how her Chinese peers might react to them, she seems confident: “Don’t all girls all over the world just want to be pretty? That is why they keep looking for new things. Fashion is changing all the time, anyway.”

Nadia and Xiwen’s fashion choices show that that there is a growing mutual bottom-up fashion exchange between China and the southern African nation Mozambique, which has a long history of adapting and integrating external cultural forms and practices into local dress. In this study, I attempt to explain what leads Chinese and Mozambicans to adopt foreign fashion elements and how this adaptation influences their perceptions of each other. The two examples above capture several phenomena that together constitute mutual Chinese-Mozambican fashion influences. Most importantly, both Chinese and Mozambicans are motivated by the quest for novelty to incorporate elements of each other’s fashion into their own outfits. In this search for “something different” and “new things,” as Nadia and Xiwen put it, they are attracted to what they consider “typical” of Chinese or Mozambican culture, such as qipao dresses and capulana fabrics. This adoption of foreign ethnic dress components entails a certain exoticization of each other. Moreover, there is a range of strategies that Chinese and Mozambicans use to gradually integrate these exotic elements into their own fashion universes, which makes the adaptation more natural and socially acceptable. As Nadia and Xiwen’s creative adaptations show, this includes subtle alterations to form and fabric, combining foreign fashion with home culture fashion, and adjusting the length of garments. These strategies also illustrate the important role of culturally determined dress norms in this adaptation process. This article furthermore shows that the adaptation of fashion elements in the Chinese-Mozambican context is different from fashion exchanges between Western and non-Western countries.

Nadia and Xiwen’s fashion choices show that that there is a growing mutual bottom-up fashion exchange between China and the southern African nation Mozambique, which has a long history of adapting and integrating external cultural forms and practices into local dress. In this study, I attempt to explain what leads Chinese and Mozambicans to adopt foreign fashion elements and how this adaptation influences their perceptions of each other. The two examples above capture several phenomena that together constitute mutual Chinese-Mozambican fashion influences. Most importantly, both Chinese and Mozambicans are motivated by the quest for novelty to incorporate elements of each other’s fashion into their own outfits. In this search for “something different” and “new things,” as Nadia and Xiwen put it, they are attracted to what they consider “typical” of Chinese or Mozambican culture, such as qipao dresses and capulana fabrics. This adoption of foreign ethnic dress components entails a certain exoticization of each other. Moreover, there is a range of strategies that Chinese and Mozambicans use to gradually integrate these exotic elements into their own fashion universes, which makes the adaptation more natural and socially acceptable. As Nadia and Xiwen’s creative adaptations show, this includes subtle alterations to form and fabric, combining foreign fashion with home culture fashion, and adjusting the length of garments. These strategies also illustrate the important role of culturally determined dress norms in this adaptation process. This article furthermore shows that the adaptation of fashion elements in the Chinese-Mozambican context is different from fashion exchanges between Western and non-Western countries.

These processes of fashion adaptation should be understood in light of the intensification of Chinese-Mozambican relations since the mid-1990s, when China and Mozambique, which used to be close allies under Mao Zedong, resumed their bilateral relations after the end of the violent Mozambican civil war (1977-1992). In Mozambique, this coincided with economic liberalization and constitutional reforms, as well as the discovery of vast natural gas resources, which made the southern African country attractive for Chinese investors.2 Therefore, China soon became very active in the Mozambican economy.3 This multilevel cooperation was institutionalized in the early 2000s through the establishment of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), a Joint Economic Trade Commission, and the Macao Forum.4 In 2011, China granted zero-tariff treatment to 60 percent of the goods imported from Mozambique, which let the trade volume between China and Mozambique further increase and resulted in China becoming a key trading partner of the African country.5 More recently, the two countries announced a “Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership,” which is supposed to be accompanied by increased Chinese investment in Mozambique's natural gas exploitation, manufacturing, agriculture, and infrastructure, as well as closer interactions between Chinese and Mozambican ministries and armed forces within the framework of Chinese president Xi Jinping’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative.6 At present, China is the largest foreign investor in the former Portuguese colony.7

According to unofficial estimates, there were between 10,000 and 40,000 Chinese nationals living in Mozambique in 2017.8 The arrival of a growing number of Chinese nationals is evidenced by the mushrooming of small Chinese shops, restaurants, and guesthouses all over Maputo9 and across the country.10 The most visible manifestations of Chinese activity in Mozambique, however, are the numerous large-scale infrastructure and construction projects,11 such as the newly finished Maputo-Katembe bridge across Maputo Bay.

The literature on cultural exchanges between Chinese and Mozambicans mainly focuses on state-led initiatives, such as the establishment of a Confucius Institute in Maputo, several scholarship programs, agreements on media cooperation,12 as well as the launch of a Chinese language degree course at Eduardo Mondlane University.13 As tools of Chinese cultural diplomacy, these activities, which in similar forms can be found all over Africa, are supposed to strengthen China’s soft power in the international community.14 As observed by Fijalkowski15 and King,16 the Chinese notion of soft power differs significantly from its conceptualization in the West. By including foreign policy, cultural diplomacy, trade incentives, and foreign aid, China uses soft power as a catch-all concept to create a positive national image, form international alliances, and position itself as a model of economic success.17

According to Chichava et al.,18 Chinese soft power initiatives in Mozambique have largely gone unnoticed by the general public. This corresponds with the findings of several other scholars, who agree on the incapacity of cultural diplomacy instruments to increase China’s soft power in Sub-Saharan Africa among other places.19 This means China has not managed to achieve the success of national branding campaigns such as “Korean Wave” and “Cool Japan.” These cultural strategies of the South Korean and Japanese governments were able to enhance the global image of the respective country’s identity by actively promoting popular culture, including music, fashion, cuisine, movies, soap operas, and cartoons.20 Fijalkowski states that “soft power is about the dynamic relationship between the agent and subject of attraction,”21 which makes clear that in order to understand the true influences on China’s image in Africa, one has to look beyond state-led forms of “high culture” relations, which is what this paper aims to do. China’s real extent of what Kurlantzick22 describes as “low” soft power, which in contrast to “high” soft power is not targeted at a country’s elite, but at the general public, can only be grasped from the perspective of people on the ground. While Tella claims that “China has not been able to win the hearts and minds of Africans through its language, music and food,”23 this study looks at another element of “low” soft power in the context of China-Mozambique relations, namely fashion.

Fashion should not be confused with clothing or dress. Other than clothing, fashion includes accessories, make-up, and body modifications.24 For a long time, the term fashion has only been used in the context of Western cultures. Describing non-Western fashion as costume or ethnic dress implied that in Asia or Africa, dress does not change and therefore lacks the cultural achievement and individual creativity that constitutes fashion.25 Several authors such as Eicher,26 Hansen,27 and Rovine28 have made clear that there indeed is a long history of creative adaptations in marginalized non-Western dress, which is why it should be called fashion, too.

There is a significant amount of literature on intercultural fashion exchanges and influences. Most of the studies relate Asian or African fashions to Western fashion, not to each other,29 even if Hansen states that “dress influences travel in all directions, across class lines, between urban and rural areas, and around the globe.”30 Moreover, scholars often focus solely on high fashion,31 leaving out the ways in which ordinary fashion32 becomes influenced by foreign aesthetics. Fashion influences among non-Western countries of the so-called “Global South”33 have been ignored by most scholars. Notable exceptions are Leslie Rabine and Nina Sylvanus. In her book The Global Circulation of African Fashion,34 Rabine proposes a model of informal linkages that remain uninfluenced by the West, along which fashion travels directly between what she calls “peripheries.” Sylvanus’ ethnographic studies on Togolese wax fabric35 traders explore Chinese involvement in the West African fabric market, its social and economic consequences,36 and the way in which it is changing Togolese perceptions of value and authenticity.37

This study sheds light on the multifaceted character of low-level cultural exchange among people of the Global South by examining the way in which Chinese nationals are adopting elements of Mozambican fashion and vice versa. In contrast to many post-colonial contexts, processes of adaptation do not emanate from a one-sided quest for modernity, but from an appetite for novelty on both sides, which leads to very specific forms of mutual fashion exoticization. These peculiar processes are also influenced by the demographic features of the persons who are most keen to adopt elements of the foreign fashion. To describe processes of mutual adaptation, I introduce a set of gradual strategies that Chinese and Mozambicans employ to harmoniously integrate foreign fashion elements into their own styles.

The data for this research was collected during five weeks of ethnographic fieldwork in Maputo, Mozambique, in Spring 2017. On-site unstructured and semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and visual analysis were supplemented by two structured phone interviews with European producers and retailers of wax print fabrics. Additionally, I conducted discourse analysis of all fashion-related articles in the online archives of two of the most widely circulated Mozambican newspapers, Domingo and Noticias.

The Global Circulation of Fashion

Fashion Globalization

In light of global systems of fashion manufacturing and distribution, various scholars have expressed concern over the worldwide homogenization of fashion and thereby the loss of local traditions.38 Indeed, many people from non-Western countries have adopted what has been called “world fashion” or “cosmopolitan fashion” by Eicher and Sumberg,39 either because they were forced to do so by colonial rulers or because they were attracted by its notion of modernity.40 Nonetheless, this patronizing fear for cultural preservation itself is a remnant of colonial Orientalist logic, as Jones and Leshkowish41 point out. Eicher and Sumberg42 clarify that even if it is typically perceived as “traditional” and never changing, “ethnic dress” is not static over time and may also include borrowed items from other cultures. Examples for this creative merging and cross-cultural fertilization can be found in the publications of Hansen, Luttmann, Rabine, Rovine, and Tarlo.43

Several scholars stress that this stylistic innovation and creativity is not restricted to the realm of high fashion, but quite the contrary, is focused on a grass-roots level.44 Therefore, the popularity of world dress does not necessarily imply “Westernization” or the disappearance of local cultural diversity. Using the example of blue jeans in West Africa, Bauer45 has made clear that cultural globalization is usually accompanied by localization and local identity building processes, which is why world fashion and ethnic dress can coexist in a closely interconnected way. Meanwhile, Zhao46 argues that in the case of Chinese fashion, Westernization has been avoided by a process which he calls “re-territorialization,” meaning the endowment of foreign fashion with local meanings.

These “layered complexities of identities and styles in an increasingly globalized world”47 have given rise to questions of authenticity and cultural identity in the realm of fashion. A very fruitful discussion of these concepts has evolved around Vlisco, a Dutch company producing wax prints for the West African market that are often copied by Chinese competitors. Several studies concluded that the authenticity of a product, in this case Dutch-produced “African” fabric, is not among its inherent characteristics, but gets ascribed to it through a complex creative process of negotiations, alignments,48 (re)appropriation,49 and counter-appropriation.50 Dutch wax cloth as a “cross-cultural commodity”51 can therefore be African and cosmopolitan, and local and foreign at the same time.52 Considering this “cultural hybridity,”53 Rabine54 even makes a case for overcoming the slippery and paradoxical concept of authenticity in relation to (African) fashion.

Another aspect of the authenticity of Vlisco fabrics concerns the “fakeness” of their Chinese counterfeits. Vann55 observes that Vietnamese fashion customers classify counterfeits as good “mimic” or bad “fake” products according to their quality and reliability. Sylvanus56 and Luttmann57 confirm these findings by showing that constructions of authenticity are shifting and Chinese copies of Vlisco fabrics can gain prestige on their own. Product authenticity is thus a highly ambiguous concept that is “constantly reconfigured, reinterpreted, and interrogated anew.”58

Fashion Exoticization

For a long time, Africans and Chinese have adopted the fashion of Western countries which they considered culturally superior and progressive to achieve a modern look for themselves.59 People from Western countries borrow elements of non-Western fashion, but they have a different motive for doing so. According to Craik, Western fashion is nothing more than “a sign of individual adornment (self-presentation), group identity and role playing.”60 Hence, there is a strong focus on what Craik calls “newness and nowness”61 meaning that Western fashion systems constantly look for new impulses to assert distinctiveness. For this purpose, foreign ethnic dress is a popular source to draw from. Examples of Western-adopted “ethnic chic” have been described by scholars, such as Bhachu,62 Clark,63 Steele and Major,64 and Tarlo.65

Following the definition of Craik, these foreign motifs in fashion can be called “exoticism.”66 The appropriation of foreign ethnic dress in a way that exaggerates the difference between “exotic” and regular fashion elements is thereby used to achieve a deliberate breach of style. Niessen et al.67 have pointed out that when ethnic dress is a mere “currency in the fashion system,”68 Orientalist stereotypes of foreign styles become reiterated. Jones and Leshkowish69 call this situation “homogenized heterogeneity,” in which difference is not only appreciated, but also commodified. This is taken to the extent that sometimes non-Western people themselves have started to exoticize their own ethnic dress and thereby engage in a practice of “self-Orientalizing.”70

Mechanisms of mutual fashion adaptation outside of these colonial or post-colonial power relations have largely been left unexplored. I propose that in this case, both sides adopt elements of each other’s fashion owing to a quest for sheer novelty and self-expression rather than an aspiration to be modern. They simultaneously adopt the position that was formerly reserved for Western countries. Following Zheng, this situation could then be described by an egalitarian model of global cultural dynamics, in which there is no cultural hierarchy, but a “flat playing field within which individual consumers are free to choose depending on their personal preferences.”71 Even if in this context, the notion of superiority that is attached to the term Orientalism72 can be spared, a certain degree of mutual exoticization is still difficult to avoid. In this instance, the two cultures mutually see each other as a source of undifferentiated exotic style. The exoticization of fashion thus exists in every cultural milieu.

Fashion Adaptation

Although the terms “appropriation” and “adaptation” are often used interchangeably, the notion of “adaptation” is more appropriate in the context of Chinese-Mozambican fashion exchanges. I use the term “adaptation” rather than “appropriation” to set apart these exchanges from the colonial and exploitative connotations that come along with the complex political and ethnological concept of cultural appropriation.73 As a strategy of change, the process of adaptation has been defined as “cultural authentication process” by Eicher and Erekosima.74 According to them, this process consists of four closely interrelated steps, namely the selection of a certain foreign practice or product as appropriate and desirable, the characterization of the foreign element with a native category, the incorporation of the element into the own culture, and finally, the transformation of the foreign element into an element of their own culture.75 In the case of fashion, Hansen76 also suggests using the terms “bricolage” or “creolization” to express the complexity and heterogeneity of this creative process of mutual adaptation.

Creativity is needed to incorporate foreign styles into one’s own fashion in a way that accommodates local dress norms in regard to etiquette and sexual decorum.77 Gradualism is one of the approaches through which global fashion inspiration and local norms can be combined in a harmonious way. Some examples of gradualist strategies include the alteration of foreign clothes by tailors,78 using them in a different way from what is customary or expected in the culture of origin,79 combining them with local clothes, and restricting their use to certain occasions.80 Looking at the incorporation of British styles and fabrics in Indian dress in the nineteenth century, Tarlo81 puts forward an especially comprehensive list of gradual variations, ranging from the use of foreign fabrics in local styles, the combination of foreign and local garments, the change from foreign to local clothes depending on the occasion, to the adoption of full foreign dress. By ranking them in a sequential order according to their degree of adaptation, Tarlo, however, neglects the possibility of combining different strategies to different degrees, which results in an indefinitely large set of individual grades of adaptation.

Most scholars writing about the adaptation of Western dress or world fashion state that men, not women, are the first to adapt their own style to a foreign fashion. Eicher and Sumberg82 assert that men are more likely to work outside of their home town, which is why they have a higher chance to come into contact with foreign ideas and styles. Another explanation given by Sylvanus83 and Ross84 is that men have a greater desire to express their modernity and “index their educational, financial, and cosmopolitan status.”85 Wearing cosmopolitan fashion might also increase their chances of getting certain jobs. In contrast, women face much stricter moral expectations towards their dress which causes them to avoid modern world dress in favor of their supposedly more traditional and therefore more appropriate ethnic dress.86 In non-colonial contexts, however, this might be slightly different. Women are an important part of fashion exchanges between Chinese and Mozambicans. In fact, my findings show that women are especially keen on trying out new fashion styles and are as (or more) likely to adopt foreign elements.

Chinese Fashion in Mozambique

Changing Supply Chains

The Mozambican textile and garment industry almost entirely collapsed in the 1990s because of mismanagement, capital and spare part shortages, and restrictive labor laws. Recent efforts by the Mozambican government to revive these industries have not been effective due to poor infrastructure, a highly bureaucratic regulatory environment, and a lack of skilled labor.87 There are a few notable exceptions, such as high fashion brands Taibo Bacar and Nivaldo Thierry, the upcycling88 fashion brand Mima-te, and the small textile company Kaningana Wa Karingana, some of which are highlighted during the annual Mozambique Fashion Week. Considering their prices and marketing strategies, however, these instances of local fashion initiative seem to exclusively cater to rather wealthy and upper-class consumers in Mozambique and abroad. Thus, the Mozambican fashion market is now dominated by second-hand clothes and imports, most of which come from China,89 but also from South Africa, Europe, and Brazil. The same applies to other fashion items and beauty products including underwear, capulanas, shoes, jewelry, hair extensions, hair products, nail polish, and whitening creams. These products are not produced in Mozambique, or if they are, they are of a very low quality, whereas their imported Western versions are not affordable for most Mozambicans.

Chinese manufacturers are able to fill this price and quality gap between Western and local or South African products, although public perceptions continue to lag, at least with regard to Chinese-made clothing. Or, as Mozambican wholesaler Tino explained to me: “China offers different qualities for different prices, that is their advantage. You can find any quality you want.” The 32-year-old trader has been traveling to Guangzhou in southern China for two years to buy clothes and beauty products, which he sells to many shops in and around Mercado Central, a large market in downtown Maputo, where he also owns a little stall.

The good quality-price ratio of Chinese products also has an impact on the ubiquitous Mozambican capulanas, cotton print fabrics usually worn as wraparound skirts. While the capulana market has long been dominated by Indian producers, most of the large capulana wholesalers in Maputo’s downtown Baixa area have now switched from Indian to Chinese suppliers. Aanesh, a shop owner of Indian descent confided that, although communication with Chinese producers is challenging sometimes due to linguistic and cultural differences, they deliver better quality for a lower price, which he attributed to the use of modern technology and the production of larger quantities. The colors of Chinese capulanas are more intense and do not run, their prints are clearer, and Chinese send fewer defective goods, he said, pointing at a pile of dirty capulanas he received from India.

In Baixa, there are even several recently opened capulana stores owned and run by Chinese (see figure 3), who buy their goods directly from China. Similar developments can be observed in the Mozambican clothing and accessories market. For a long time, Chinese fashion came in mainly via third countries such as South Africa, Brazil, or Portugal.90 In the last few years, the number of local direct importers such as Tino has increased, but they now have to compete with Chinese traders, who often benefit from their Chinese language skills and their close connections to the producers in China.

In Baixa, there are even several recently opened capulana stores owned and run by Chinese (see figure 3), who buy their goods directly from China. Similar developments can be observed in the Mozambican clothing and accessories market. For a long time, Chinese fashion came in mainly via third countries such as South Africa, Brazil, or Portugal.90 In the last few years, the number of local direct importers such as Tino has increased, but they now have to compete with Chinese traders, who often benefit from their Chinese language skills and their close connections to the producers in China.

Local Perceptions of Chinese Product Quality

Wholesaler Tino proudly shows me around the empty space close to the Mercado Central that will become his first fashion store. Spacious and painted white, Tino’s Fashion will stand in stark contrast to the crammed little shops in the surrounding streets. Upon completion, he is planning to offer “good quality Chinese clothes” for women, men, and children. He explains: “So far, Mozambicans don’t like Chinese[-made] clothing because they only know the cheap and poor-quality stuff imported by Nigerians.” Tino, however, “knows about fashion,” so he can easily find high-quality clothing in China. Indeed, for some time, many Mozambican consumers have had a rather negative opinion of Chinese products such as electronics and clothing, which are associated with poor workmanship, inferior materials, and a short lifespan. With the influx of Chinese beauty and fashion products, however, these perceptions are changing.

As many Chinese clothes are still imported via other countries, Mozambicans are often unaware of the origin of the clothes they wear and just assume they are from Brazil or Portugal. In some cases, even the vendors are oblivious of the true origin of the garments they sell. This confusion enables Mozambicans to enjoy the style and quality of Chinese products without being biased. This kind of unconscious endorsement can also be observed in the case of capulanas. Unlike West Africans, Mozambican consumers do not pay attention to brand or origin when buying print fabrics. Thus, they are easily convinced by the good fabrics, and the pretty and innovative designs of Chinese capulanas. Another reason Mozambicans may value Chinese products is the way these products help them to achieve the Western or Brazilian style they desire. Slimming and buttock enhancing shapewear from China (see figures 4 and 5), for example, is very popular as it permits Mozambican girls and women of any build to wear the much-loved tight-fitting jeans and dresses imported from Brazil.

Yet, by early 2017, Mozambicans had started to appreciate more and more Chinese products as such. The most prominent manifestation of this trend is KAQIER,91 a leave-in conditioner hair spray for curly hair from the product range of the Guangzhou KAQI Daily Cosmetic Factory, which became popular in Mozambique in 2016, and Unique,92 a high-quality synthetic hair brand, which enables Mozambican girls and women to obtain the quality of real hair extensions for a much lower price. These products may be helping change widely held negative perceptions of Chinese quality. Another factor that contributes to the slowly growing Mozambican appreciation of Chinese products is a very particular understanding of what is fake and what not. Tino, for example, told me that he will not sell “pirated goods” (piratas) in his new shop, but rather “good quality European-style clothes, for example Gucci, Nike, Adidas, Puma.” He does not consider these Chinese counterfeits of Western brand name products fake, as they are made of high-quality materials such as real leather. For him and several of my other Mozambican informants, pirata stands for inferior quality, not for counterfeit. This is largely consistent with Sylvanus’93 finding that Togolese conceptions of value have changed in reaction to Chinese counterfeits of Dutch wax print fabrics. It also explains why a Mozambican lady chose to go to a Chinese supermarket to buy Blackhead shampoo, a Chinese knock-off of the German brand Schwarzkopf. She bought this product solely for its good qualities and was fully aware of it being a counterfeit, which is why she described it as “a copy, but a good one” (uma copia, mas uma copia boa).

The Influx of Chinese STYLE

The shift towards Chinese producers in Mozambican fashion supply chains described above entails the influx of Chinese styles and aesthetics. As there is a steady demand for new patterns and motifs, many capulana wholesalers receive new collections from China weekly or every other week. These capulanas are often not only produced, but also designed in China, which is why they sometimes include novel and distinctly Chinese motifs such as yin-and-yang symbols. However, “Chinese” capulana designs enter the Mozambican market not only via China. Chinese-style motifs such as dragons are so popular that they can also be found on Indian-made capulanas (see figure 6). This transnational circulation of designs stands in the long tradition of African print fabric making, which is characterized by cultural hybridity and cross-cultural fertilization.94

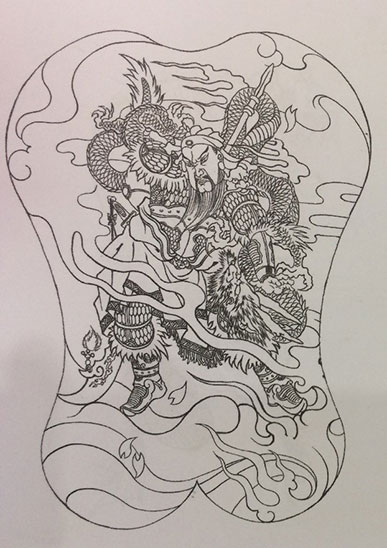

Sometimes, Chinese-style products appear on the Mozambican market rather randomly as a result of the assortment expansion of local wholesalers who have familiarized themselves with the full range of Chinese products. Concomitant with these traders’ shopping sprees in China or at Chinese wholesalers, “typically Chinese” products end up in their stores. Thus, little silk-covered boxes and lipstick cases of a distinctly Chinese design can be found among other cheap Chinese paraphernalia in local beauty shops (see figure 7). The owner of a popular tattoo studio in Western Maputo found two tattoo sample books from China when he was purchasing tattoo supplies (see figure 8), and these books are now in daily use at the shop. Some of their templates are very popular with customers, just like the little silk boxes. Soon-to-be shop owner Tino confirmed that despite Mozambican consumers’ still-prevailing distrust in Chinese quality, there is a certain demand for Chinese-style clothes and accessories in Mozambique. While he does not plan to sell such products at the moment, he says that he is open to exploring the possibilities in the future.

Novelty and Exotic Appeal as Drivers of Adaptation

The Global Homogenization of Fashion

The demand for fashion produced in China is indirectly caused by the fact that not only supply chains become globalized, but also tastes and styles. To illustrate, Mozambican second-hand clothing customers usually do not see a difference between the styles of second-hand clothes from China and Western countries. For them, these clothes differ only in size and quality, with clothes from China regarded as lower quality. Chinese and Mozambicans perceive global fashion as increasingly homogenous, as they get used to the prevalence of world fashion, such as jeans and plain T-shirts.

While Eicher and Sumberg95 deliberately refuse to call these kinds of clothes “Western fashion,” as it is now worn by people in all parts of the world, this notion is still common among Chinese as well as Mozambicans. Hence, wholesaler Tino says that the clothes he imports from China have “Western style” or “US style,” or just “whatever is in fashion.” The term typically used by Chinese is xifu 西服, a direct translation of “Western clothes.” This expression has even been adopted by the Mozambican students of the Confucius Institute at the Eduardo Mondlane University, who told me that the Chinese students they met at their partner University in China as well as the Chinese teachers at the Confucius Institute usually just wear the same xifu as they do. This is why they do not observe a difference in everyday clothing style between their Chinese peers and themselves.

Their male Chinese teacher Mr. Wei, however, drew a distinction between male and female fashion in this regard. For him, “there is no big difference in men’s clothing style, be it in Mozambique, China, or the US.” He continued: “It might be different for women; there are more distinct style differences.” This impression in relation to gender corresponds with the observation of Ross96 that male fashion has become globally uniform to a higher degree than female fashion.

Foreign Ethnic Dress as Novelty

As fashion is all about “rapid and constant change,”97 Chinese and Mozambicans increasingly look for novelties in light of a homogenized world fashion. This becomes most evident when looking at Mozambican capulana shopping habits. When former fashion shop employee Nadia and I wanted to buy matching capulanas for National Women’s Day, it took us two days to finally decide on a certain print. This was not only because of our different tastes, but mainly due to the demands Nadia placed on the product. Apart from having a “sturdy” (resistente) fabric and “vivid colors” (cores vivas) which currently are “in fashion” (na moda), a capulana most importantly must be a “novelty” (novidade), i.e., a new design. Therefore, she decided against a capulana with a pattern that had already been popular last year, even though we both liked it very much. Nadia told me that she will immediately recognize a capulana that has already been on the market for several weeks or months. These “old ones” (antigos) can still be worn at home but are not appropriate to wear at special events such as weddings or Women’s Day. Several capulana traders confirmed that the importance of novidade cannot be underestimated and even bestselling patterns have to be amended continuously to retain popularity, which is why all the capulanas they offer are, at maximum, two to three months old. The same pertains to Chinese tastes as for instance the administrative secretary Xiwen (introduced at the beginning of this article), who constantly looks for new things to include in her wardrobe.

Especially suitable for this purpose is ethnic dress, which is often seen as the opposite of world fashion;98 Chinese and Mozambicans are indeed attracted by fashion elements that they consider “typical” of the other culture. For a Chinese person, such things as Mozambican capulana fabrics and braided hairstyles might be considered “typical.” These are the elements of Mozambican fashion that come first into the mind of a young female Chinese teacher at the Confucius Institute. She considers clothes made of capulana fabric “very pretty” and “very special and different” (hen you tese, hen bu yiyiangde 很有特思,很不一样的). She admires their bright colors and will bring some “typical African clothes” (feizhou tese yifu 非洲特色衣服) as gifts for her family at home. She would also like to get one of the “fun” (hen haowan 很好玩), “very interesting” (henyouyise 很有意思) and “ingenious” (lingqiao 灵巧) Mozambican hairstyles, but is afraid that she is “not skilled enough” (bu tai shulian 不太熟练) to make braids herself.

For their part, Mozambicans are especially drawn to dragon patterns, Chinese characters, and the qipao dress. Chinese dragons and characters are popular tattoo designs “because they are different” and “more personal” (coisa mais pessoal), since not everyone will understand them, a Maputan tattoo studio employee explained to me. Often deemed the Chinese national dress,99 the qipao is seen by Mozambicans as the direct counterpart of the capulana. They keenly incorporate elements of it into their own fashion. There is a tailor at Mercado Janet, who has put two “Chinese dresses” (vestidos chineses) on display in his little stall (see figures 9 and 10). The dresses, made of capulana fabrics, with the typical short sleeves, side slits, and round stand-up collar of the qipao, were commissioned by Mozambican customers. When I asked the tailor whether his Chinese customers sometimes order qipao-style dresses, too, he just laughed: “No, the Chinese want African style clothing only!”

Neither the Chinese nor the Mozambicans see the other country as an explicit reference point for modernity or cultural progressivity. Chinese commonly assert that Mozambicans are backwards and of “low personal quality” (suzhi di 素质低). And Chinese culture is still a long way from gaining the high prestige accorded to Chinese technology, which is already regarded as progressive and superior by many Mozambicans. The Mozambican employees of a large Chinese supermarket in the center of Maputo, for example, were very disapproving of the fact that their Chinese bosses still spoke poor Portuguese, even though they had lived in Mozambique for several years already. They complained about the rude and authoritarian demeanor of the Chinese managers, who are said to have “hearts of stone” (coracoes de pedra). Apart from being harsh employers, Chinese are also considered to be “racists” (sao racistas) and to “not have love” (nao tem amor), which implies a lack of empathy and benevolence.

Therefore, Chinese and Mozambicans are equally in pursuit of novelty and self-expression, which is the main reason that motivates them to adopt elements of each other’s fashion. Although there remains a certain power asymmetry related to differences in wealth, global influence, development status, and economic strength, Chinese-Mozambican relations in the area of personal fashion are more egalitarian than these kinds of relations between the West and Asian or African countries.

Mechanisms of Mutual Exoticization

By adapting elements of foreign ethnic dress in order to establish distinctiveness, Chinese and Mozambicans exoticize the fashion of the other. In this process, they commonly generalize the foreign culture. Just like the young Chinese teacher at the Confucius Institute, who wants to buy “typical African clothes,” many Chinese indiscriminately use the term “African” when they actually mean “Mozambican.” They thereby implicitly deny the singularity and distinctiveness of Mozambican culture and lump it together with the cultures of other African countries. In a similar vein, they use the general term “blacks” (heiren 黑人) to talk about Africans of any nationality, be they Mozambican or not.

Meanwhile, Mozambicans usually do not draw a distinction between Chinese and other Asian cultures, as well. For example, I met a Mozambican girl on the street in Southern Maputo, who had a clearly visible tattoo of the simplified Chinese character for “love” (ai 爱) on her chest, which was slightly “misspelled” with a few strokes missing. Asked about her reasons for choosing this motif, she first told me that it means “love” in Japanese and then went on to say that she looked up the motif on the internet because she wanted to have a Chinese character. (In Japan this character is written with the traditional Chinese character 愛.) The fact that she mixed up Mainland China, where simplified characters are used, and Japan, whose writing system includes loaned Chinese characters (called kanji in Japanese), shows that she does not have a deep understanding of either these cultures or their writing systems, and is merely interested in the exotic appeal of Asian aesthetics in general. Often, Mozambican tattoo artists likewise cannot tell the difference between Chinese and Japanese motifs.

However, it is important to note that Mozambicans as well as Chinese are ambiguous about the distinctiveness of their own fashions. Among Mozambicans, there is a common confusion and ambiguity about the identity-giving and symbolic meaning of the capulana. While sellers always stress that the design and thereby the character of the (often Chinese-produced) fabrics is Mozambican or “100% national” (cem porcentos nacional), many Mozambicans associate capulanas with “Africanism” (africanismo) instead of “Mozambicanism” (mocambicanidade). This is not surprising, as Indian-made capulanas were originally brought to Mozambique by via Kenya and Tanzania and are now worn – under different names and with different designs – in many African countries.100 A look into Mozambican newspapers shows that this double symbolism of the capulana does not need to be contradictory. Capulanas are seen as an expression of femininity and mocambicanidade, but at the same time identify the wearer as African.101 According to another article published in Domingo, Mozambican fashion builds on African roots as well as on past international influences from Arabs, Persians, and even Chinese, which is reflected in the capulana as a cultural symbol.102 This way, the capulana can at once be an “object of the blending process of globalization” (objeto de globalização liquidificadora) and an affirmation of Mozambican identity.103

The Chinese in Mozambique are definitely more aware of the distinctiveness of their own dress culture. They have, for example, very clear conceptions of what a qipao should look like. When I showed them pictures of the qipao-style capulana dresses I found at Mercado Janet (see figures 9 and 10), many Chinese stated that a qipao is not a qipao anymore if it is made of capulana fabric, which they consider to be unsuitable for a qipao, as it is too thin and not smooth enough, resulting in wrinkles and uneven seams. It can also not be worn by a curvy Mozambican girl, as according to them, the cut of a qipao has to be straight and slender.

As mentioned in the works of Chan,104 Finnane,105 and Zhao,106 the qipao is not as “typically Chinese” as commonly believed. Based on Manchu women’s dress (hence the name “qipao” 旗袍 or “banner robe”), influenced by Western designs and tailoring techniques, embraced by the Nationalists, and popular in other countries like Singapore, the qipao is still highly contested in its unofficial role of a national dress. This ultimately makes the mutual cultural incomprehension between Chinese and Mozambicans a reiteration of already existing cultural ambiguities in the two countries.

Variables of Fashion Adaptation

Strategies of Gradualism

Looking at the ways in which Chinese and Mozambicans adapt to each other’s fashion tastes, a complete and permanent appropriation is extremely rare. Instead, there is a set of strategies that both employ to adjust the level of adaptation to their personal needs and tastes. By availing themselves of a gradualist approach, people are able to incorporate foreign fashion elements into their own fashion universe in a harmonious and socially acceptable way. The strategies can be divided into methods related to the gradation of scope, form, source, and time. This order does not constitute any ranking, as each of the methods can be applied to different degrees independently of each other, and in any individual combination.

Looking at the ways in which Chinese and Mozambicans adapt to each other’s fashion tastes, a complete and permanent appropriation is extremely rare. Instead, there is a set of strategies that both employ to adjust the level of adaptation to their personal needs and tastes. By availing themselves of a gradualist approach, people are able to incorporate foreign fashion elements into their own fashion universe in a harmonious and socially acceptable way. The strategies can be divided into methods related to the gradation of scope, form, source, and time. This order does not constitute any ranking, as each of the methods can be applied to different degrees independently of each other, and in any individual combination.

The most obvious strategy is the adjustment of scope. Adaptation of foreign style can involve a whole outfit or be limited to certain parts of it. As seen in the introductory examples, Nadia and Xiwen mix garments inspired by the fashion tastes of the other with their regular clothes and accessories. A lower degree of adaptation is achieved by Chinese who commonly confine themselves to wearing Mozambican accessories, such as flip-flops, or bags, hats, or pieces of jewelry made of capulana fabric. Combined with world fashion, including jeans, T-shirts, sunglasses, or trainers instead of ethnic dress, foreign fashion elements lose a part of their strangeness and fit in more harmoniously. World fashion thus acts as a facilitator.

More elaborate than the variation of scope seems to be the variation of form, including design elements, motifs, and sewing patterns. The employee of the tattoo studio mentioned in an earlier section explained that compared to Chinese customers, Mozambicans seldom pick “very Chinese” tattoo motifs such as warriors or deities from Chinese mythology (see figure 11). One of the studio’s most popular motifs from their sample books is a black-and-white fish, which is drawn in a distinctly Asian style but is not associated with Chinese history or mythology (see figure 12), even though it has a certain symbolic meaning implying abundance. Similar patterns can be observed in the case of clothing design. Mozambicans do not necessarily adopt the whole sewing pattern of the Chinese qipao but rather only certain elements of it, as in the case of the two capulana dresses at the Mercado Janet tailor shop. Shirts, blouses, and dresses with a “Chinese collar” (gola chinesa) worn by Mozambican men and women are a common sight on the streets of Maputo. Incorporating Chinese style elements to a degree that lies right in between these regular garments with Chinese collars and the capulana-made qipao dresses, Nadia’s dress offers another example. She ordered a knee-length bespoke garment to combine qipao-style collar and short sleeves with a V-neck and a golden zipper which runs prominently down the whole back of the dress (see figures 13 and 14).

The prevalence of tailors, most of whom come from West African countries that have a longer tradition of tailor-made clothing, combined with the omnipresence of the capulana in Mozambique, greatly facilitates individual grades of adaptation in form. Due to their large variety and stylistic flexibility, capulana fabrics can not only be fashioned into Chinese forms without great effort, but also make it easier for Chinese to integrate Mozambican patterns and motifs into their wardrobes. Customers can choose the pattern, colors, and designs they like and thereby achieve a level of adaptation they are pleased with, just like Xiwen in the vignette at the start of this article, who picked a capulana in a “not too African” design to get a personalized dress made of it. Generally, Chinese do not use capulanas in their basic form as unsewn wraparound skirts. If tailored in a cosmopolitan design, however, Chinese are more likely to wear them. When I ordered capulana tailor-made trousers in the style of my favorite pair of jeans, for instance, I received many compliments and curious requests from Chinese women, who wanted to get the same trousers.

The prevalence of tailors, most of whom come from West African countries that have a longer tradition of tailor-made clothing, combined with the omnipresence of the capulana in Mozambique, greatly facilitates individual grades of adaptation in form. Due to their large variety and stylistic flexibility, capulana fabrics can not only be fashioned into Chinese forms without great effort, but also make it easier for Chinese to integrate Mozambican patterns and motifs into their wardrobes. Customers can choose the pattern, colors, and designs they like and thereby achieve a level of adaptation they are pleased with, just like Xiwen in the vignette at the start of this article, who picked a capulana in a “not too African” design to get a personalized dress made of it. Generally, Chinese do not use capulanas in their basic form as unsewn wraparound skirts. If tailored in a cosmopolitan design, however, Chinese are more likely to wear them. When I ordered capulana tailor-made trousers in the style of my favorite pair of jeans, for instance, I received many compliments and curious requests from Chinese women, who wanted to get the same trousers.

The third strategy concerns the choice of different sources. Even if they are attracted by Mozambican aesthetics, Chinese are often reluctant to buy Mozambican fashion items for their own use from street vendors and market stalls like most Mozambicans do. Huili, for example, the wife of a Chinese entrepreneur from Henan province, who has been staying with her husband and her five-year-old son in Maputo for the past year, has bought her regular rose-colored flip-flops in a large seaside shopping center, although she could have purchased the same pair of the same brand of sandals at a street stall for half the price. Her son is also wearing a sun hat made of colorful capulana fabric, which Huili got from an upscale local handicrafts store in a popular expat area. This behavior cannot solely be explained by linguistic convenience. She only speaks a little English and Portuguese, and there is no Chinese spoken in either the shopping center or at street stalls. Therefore, in both places it is equally difficult for her to communicate. International places such as expensive shopping centres and European-owned boutiques moderate style- and quality-related uncertainty and thereby serve as intermediators between Mozambican fashion and Chinese customers.

The fourth strategy pertains to temporal aspects of adaptation, meaning how permanently and how frequently persons commit themselves to a foreign fashion. While a tattoo certainly constitutes the longest-lasting commitment, braided hairstyles or foreign-style outfits are of a more temporary nature. People also tend to make their level of foreign fashion adaptation dependent on the occasion. Xiwen’s Mozambican co-worker owns a traditional Chinese-style qipao dress made of shiny silk-like fabric, but she only wears it occasionally, usually when she is at the Chinese company she works for. In the most extreme cases, some Chinese only change into Mozambican clothes to take funny pictures with their friends. Nadia wears her Chinese-style dresses to go out or to attend class at her vocational school, but she would not wear them to church, where capulanas are considered more appropriate.

The Role of Dress Norms

Social dress norms have a determining influence on the manner and degree to which Chinese and Mozambicans adapt to foreign fashion. When choosing their outfits, both Chinese and Mozambicans face unofficial local dress rules they eventually must comply with to avoid alienation. Mozambicans and Chinese have to find ways and means to navigate these norms while incorporating foreign elements into their fashion.

Mozambican women especially pay a lot of attention to “decent clothes” (roupa decente). To be a “reputable woman” (mulher digna), they avoid wearing hot pants and sleeveless tops starting around the age of 18, confining themselves to long trousers and skirts that reach down to the knee when in public. When dressing for work or school, Mozambican girls and women ensure that the hem of their shirt or blouse ends below the waistband and that their clothes are not too tight. As the majority of Chinese second-hand clothes and garments on offer in Chinese shops are available in small sizes only, Mozambicans have to resort to tailor-made clothes or else have off-the-rack Chinese-style garments altered, just as Nadia did when she wore her qipao-style dress as a top when it was deemed inappropriately short. In one Noticias article, journalist Mutenda107 scorns short skirts as un-Mozambican and praises women who lend capulanas to “badly dressed” (mal vestida) girls on the street. Nadia explained that every Mozambican woman is indeed expected to carry a spare capulana with her when she leaves the house. This custom “is part of the female hygiene” (faz parte da higiene da mulher) and enables women to cover parts of their body, if they, for example, spontaneously decide to attend a church service. It also makes it easier for them to wear Chinese-style fashion in daily life, as they can switch back to what is considered proper attire at any time.

After spending some time in Mozambique, most Chinese become aware of these norms, too. While newly arrived Chinese of all genders usually wear shorts which they purchased in China in preparation for their trip, they soon realize that despite the hot weather, the beach is the only place in Mozambique where it is appropriate to wear short trousers. Hence, they revert to wearing long trousers. Huili, the housewife from Henan, was also told by other Chinese that it is not “polite” or “respectful” to wear shorts in public, which is why she and her husband now only wear them at home. Mr. Wei, the Confucius Institute teacher, was surprised to find out that Mozambicans look down on him when he is wearing shorts, but at the same time they find flip-flops in class or at the office perfectly acceptable. Like many Chinese, he considers flip-flops too sloppy and “informal” (bu zhengshi 不正式) for wearing in public. Convinced by their comfort and convenience, most Chinese nonetheless quickly adapt to this Mozambican habit and start wearing flip-flops, too. This also applies to Chinese individuals who otherwise reject Mozambican fashion. As many Chinese do not intend to stick to their long trousers or flip-flops after their return to China, these fashion adaptations based on foreign dress norms are of a rather temporary nature.

Sociodemographic Factors

Sociodemographic factors such as gender and education greatly influence, and arguably facilitate, the adaptation of fashion elements. Well-educated women of both nationalities are more likely to adopt elements of each other’s fashion. Because in the case of China and Mozambique the adaptation of the other fashion neither has the connotation of modernity nor is a prerequisite for employment, there is no compelling social or economic reason for men to strive for it. In this context, the main purpose for incorporating foreign elements is the achievement of a novel, distinct, and fashionable individual look, which nowadays is usually seen as something that women care about more. So even if there usually are higher moral expectations towards women’s dress, Chinese and Mozambican women show more receptivity towards foreign styles and are more likely to invest time and money to integrate these styles into their wardrobes in comparison to men.

Apart from gender, education and cultural awareness are important determining factors of the degree to which a person is willing and able to not only appreciate but also to adopt foreign styles. Accordingly, Chinese and Mozambicans with a higher level of education tend to have a better-informed opinion of culture and fashion of the other than their less educated peers. The young female Chinese teacher, for example, got in touch with African styles for the first time at high school. She had African classmates who came to her school as exchange students and also offered braid making at the annual school festival. This might be one of the reasons why she is now so open to Mozambican hair and clothing styles. Likewise, her colleague Mr. Wei said that buying capulanas can also be an interesting cultural experience. A similar level of cultural awareness is displayed by his Mozambican students, who are especially appreciative of Chinese fashion and aesthetics, which they got to know during their stays in China.

International experience alone, however, is no guarantor of fashion-related open-mindedness. Take the case of Zheng, a 28-year-old hairdresser from Liaoning province in northeastern China, who has been living in Mozambique for nine years after dropping out of high school and being unable to find a well-paid job in his native country. He has been travelling to various African countries, has a good command of Portuguese, and claims to “have adapted” (shiying le 适应了) to life in Mozambique. Nonetheless, he cannot recognize any beauty in Mozambicans and their fashion. He does not consider Mozambican fashion “fashionable” (shishang 时尚) at all. His benchmark for fashionability is Korean fashion and he is not able to appreciate any fashion styles that deviate from this aesthetic ideal, which is why he gets all his clothes imported from China. The same applies to a masseuse from Sichuan, as well as to a 22-year-old supermarket employee from eastern Chinese Anhui province named Jiashun. He thinks capulanas are backward and old-fashioned and says that he prefers “modern” (xianzai de 现在的) things. Unsensitized to cultural differences by higher education, he strictly adheres to his “modern” fashion and even refuses to wear flip-flops.

Conclusion: Implications for Chinese Soft Power

In this paper, I have examined why and how Chinese and Mozambicans adopt elements of each other’s fashion. This study sheds light on the circulation of fashion and styles among non-Western countries. Against the backdrop of transnational economic systems of production and consumption, Chinese aesthetics reach Mozambique as a side effect of the influx of Chinese-made fashion products into the country, where they are able to fill a price and quality niche between Western and local fashion products. These products are increasingly popular in Mozambique due not only to their affordability and emulation of a Western style, but also their inherent quality. The improving reputation of Chinese fashion products therefore has the potential to positively influence Mozambican perceptions of Chinese product quality in general.

Facing the global prevalence of a highly homogenous world fashion, Chinese migrants and Mozambicans look for novel fashion ideas, which they often find in the ethnic dress of the other country. Both sides are primarily motivated to adopt elements of each other’s fashion by a wish for self-expression and a novel look that sets them apart from their peers. Their practices and attitudes differ from the adoption of foreign fashion in colonial and post-colonial contexts, which was and is premised on the pursuit of modernity. Resembling such contexts, however, Chinese-Mozambican fashion adaptations are accompanied by a certain degree of mutual exoticization, which is evidenced by the generalizing and undifferentiating way Chinese and Mozambicans each talk about the fashion of the other.

As personal fashion is always determined by culture-dependent dress norms, foreign fashion is rarely adopted completely and permanently. To bring foreign aesthetics into accordance with these norms, Chinese and Mozambicans employ a set of strategies that allows them to gradually vary the degree to which they incorporate foreign elements into their own style universe. By adjusting the individual level of adaptation, people can find a middle ground between what is stylish and novel, yet nonetheless deemed appropriate by society. Moreover, these strategies enable women to overcome the moral requirements imposed on their dress and initiate mutual fashion adaptation in the context of Chinese-Mozambican relations.

Even if this ethnographic study conducted in Maputo cannot claim to be representative for the whole of Mozambique or the whole of Africa, it suggests that bottom-up fashion exchange between non-Western countries is multifaceted and has specific characteristics that distinguish it from fashion exchanges between Western and non-Western countries. By doing so, it might contribute to a better understanding of Chinese soft power. To begin with, this article shows that China has indeed “low” soft power in the form of Chinese fashion, which is widely appreciated by the Mozambican public. Completely independent from official cultural diplomacy, purely bottom-up, and depending on fluctuating trends, Chinese fashion as a source of soft power is, however, difficult to control by the Chinese government. Another indicative implication for Chinese soft power is that certain popular Chinese products have the potential to improve the reputation of Chinese-produced goods in general. Therefore, it might be beneficial for the Chinese government, in its effort to enhance soft power in Africa, to promote and regulate the export of high-quality Chinese fashion products to African countries. To determine the extent to which these findings apply to other African countries and other areas of “low” soft power, such as food, movies, or home decoration, further research is needed. Such research could also shed light on whether and how encounters with African fashions abroad have a lasting effect on the personal style of individual Chinese.

Acknowledgements

Johanna von Pezold wants to thank Dr. Miriam Driessen at the University of Oxford for being the most enthusiastic and encouraging master thesis supervisor she could have wished for.

Bibliography

Alden, Chris, and Sérgio Chichava, eds. China and Mozambique: From Comrades to Capitalists. Auckland Park, South Africa: Jacana Media, 2014.

Banze, Carol. “Vestido de Capulana no Corpo e Na Alma [Capulana clothing on the body and in the soul].”, Domingo, June 6, 2015. Accessed May 19, 2017.

Bauer, Kerstin. “ʻBlue Jeans are Turning the World Blue’: Jeanshosentragen in Westafrika [Wearing jeans in West Africa].” In Mode in Afrika: Mode als Mittel der Selbstinszenierung und Ausdruck der Moderne [Fashion in Africa as a means of self-dramatization and expression of modernity], edited by Ilsemargret Luttmann, 119–23. Hamburg: Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg, 2005.

———. “ʻOther People’s Clothes’: Secondhandkleider in Westafrika [Second-hand clothes in West Africa].” In Mode in Afrika, 124–27.

Bernard, H. R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 5th ed., Lanham MD: AltaMira Press, 2011.

Bhachu, Parminder. Dangerous Designs: Asian Women, Fashion, and the Diaspora Economies. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Bruggeman, Danielle. “Vlisco: Made in Holland, Adorned in West Africa, (Re)Appropriated as Dutch Design.” Fashion, Style & Popular Culture 4, no. 2 (2017): 197–214.

Chan, Annie. “Fashioning Change: Nationalism, Colonialism, and Modernity in Hong Kong.” Postcolonial Studies 3, no. 3 (2000): 293–309.

Chew, Matthew. “Contemporary Re-Emergence of the Qipao: Political Nationalism, Cultural Production and Popular Consumption of a Traditional Chinese Dress.” The China Quarterly 189 (2007): 144–61.

Chichava, Sérgio. “Mozambique and China: from Politics to Business?” IESE Discussion Paper, no. 5 (2008).

Chichava, Sérgio, Lara Cortes, and Aslak Orre. 2014 “The Coverage of China in the Mozambican Press: Implications for Chinese Soft Power.” Paper presented at the conference China and Africa Media, Communications and Public Diplomacy, Chr. Michelsen Institute, Beijing, 10-11 September, 2014.

Chichava, Sérgio, and Jimena Duran. “Migrants or Sojourners? The Chinese Community in Maputo.” In China and Mozambique, 188–98.

Chichava, Sérgio, Jimena Duran, Lídia Cabral, Alex Shankland, Lila Buckley, Lixia Tang, and Yue Zhang. “Chinese and Brazilian Cooperation with African Agriculture: The Case of Mozambique.” CBAA Working Paper, 2013.

Clark, Hazel. The Cheongsam. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Conklin, Beth A. “Body Paint, Feathers, and VCRs: Aesthetics and Authenticity in Amazonian Activism.” American Ethnologist 24, no. 4 (1997): 711–37.

Corkin, Lucy J. “China’s Rising Soft Power: The Role of Rhetoric in Constructing China-Africa Relations.” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 57, special edition (2014): 49–72.

Craik, Jennifer. The Face of Fashion: Cultural Studies in Fashion. London: Routledge, 1994.

Daliot-Bul, Michal. “Japan Brand Strategy: The Taming of 'Cool Japan' and the Challenges of Cultural Planning in a Postmodern Age.” Social Science Japan Journal 12, no. 2 (2009): 247-66.

Delhaye, Christine, and Rhoda Woets. “The Commodification of Ethnicity: Vlisco Fabrics and Wax Cloth Fashion in Ghana.” International Journal of Fashion Studies 2, no. 1 (2015): 77–97.

Domingo. “Capulanas e Africanidades [Capulanas and Africanities].” June 6, 2015. Accessed May 19, 2017.

Edoh, M. Amah. “Redrawing Power? Dutch Wax Cloth and the Politics of ‘Good Design’.” Journal of Design History 29, no. 3 (2016): 258–72.

Eicher, Joanne B., ed. Dress and Ethnicity: Change Across Space and Time. Oxford: Berg, 1995.

———. “Fashion of Dress.” In National Geographic Fashion, edited by C. Newman, 16–23. Washington DC: National Geographic Society, 2001.

Eicher, Joanne B., and Tonye Erekosima. “Why Do They Call it Kalabari? Cultural Authentication and the Demarcation of Ethnic Identity.” In Dress and Ethnicity, edited by Joanne B. Eicher, 139–63. Oxford: Berg, 1995.

Eicher, Joanne B., and Barbara Sumberg. “World Fashion, Ethnic, and National Dress.” In Dress and Ethnicity, 295–306.

Feijo, Joao. “Mozambican Perspectives on the Chinese Presence: A Comparative Analysis of Discourses by Government, Labour and Blogs.” In China and Mozambique, 146–87.

Figueiredo, Paulo. “Mozambique and China: A Fast Friendship into the Future.”, Macauhub, August 19, 2016. Accessed October 20, 2016. http://www.macauhub.com.mo/en/2016/08/19/mozambique-and-china-a-fast-friendship-into-the-future/.

Fijałkowski, Łukasz. “China’s ‘Soft Power’ in Africa?” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 29, no. 2 (2011): 223–32.

Finnane, Antonia. Changing Clothes in China: Fashion, History, Nation. London: Hurst, 2007.

French, Howard W. China’s Second Continent: How a Million Migrants are Building a New Empire in Africa. New York: Knopf, 2014.

Global Times. “China, Mozambique Establish Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership.”, May 18, 2016. Accessed November 22, 2016. https://www.globaltimes.cn/

Gott, Suzanne. “The Dynamics of Stylistic Innovation and Cultural Continuity in Ghanaian Women’s Fashions.” In Mode in Afrika, 61–79.

Green, Denise N., and Susan B. Kaiser. “Fashion and Appropriation.” Fashion, Style & Popular Culture 4, no. 2 (2017): 145–50.

Hansen, Karen T. Salaula: The World of Secondhand Clothing and Zambia. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2000.

———. “The World in Dress: Anthropological Perspectives on Clothing, Fashion, and Culture.” Annual Review of Anthropology 33, no. 1 (2004): 369–92.

Hartig, Falk. “New Public Diplomacy Meets Old Public Diplomacy – the Case of China and Its Confucius Institutes.” New Global Studies 8, no. 3 (2014): 331–52.

Hendrickson, Hildi, ed. Clothing and Difference: Embodied Identities in Colonial and Post-Colonial Africa. Durham: Duke University Press, 1996.

Jennings, Helen. “A Brief History of African Fashion.” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 2015, no. 37 (2016): 44–53.

Jones, Carla, and Ann M. Leshkowish. “Introduction: The Globalization of Asian Dress: Re-Orienting Fashion or Re-Orientalizing Asia?” In Re-Orienting Fashion, edited by Sandra Niessen, 1–48. Oxford: Berg, 2003.

Joo, Jeongsuk. “Transnationalization of Korean Popular Culture and the Rise of “Pop Nationalism” in Korea.” The Journal of Popular Culture 44, no. 3 (2011): 489-504.

King, Kenneth. China’s Aid & Soft Power in Africa: The Case of Education & Training. Woodbridge: Currey, 2013.

Kurlantzick, Joshua. Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power is Transforming the World. New Haven, Conn.: Yale Univ. Press, 2007.

Kuwahara, Yasue, ed. The Korean Wave: Korean Popular Culture in Global Context. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Luttmann, Ilsemargret. “Einführung [Introduction].” In Mode in Afrika, 7-16.

———, ed. Mode in Afrika: Mode als Mittel der Selbstinszenierung und Ausdruck der Moderne [Fashion in Africa as a means of self-dramatization and expression of modernity]. Hamburg: Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg, 2005.

Munhisse, Euclides F. “Capulana: Resgate da Tradição ou Moda? [Capulana: saviour of tradition or fashion?].”, Noticias, 2016. Accessed May 19, 2017.

Mutenda, Mendes. “Sociedade Civil e as Saias Compridas [Civil society and long skirts].”, Noticias, 2016, accessed May 23, 2017, http://www.jornalnoticias.co.mz/index.php/assim-vai-o-mundo/55106-cunha-....

Niessen, Sandra. “Afterword: Re-Orienting Fashion Theory.” In Re-Orienting Fashion, 234–66.

———, ed. Re-Orienting Fashion: The Globalization of Asian Dress. Oxford: Berg, 2003.

Njal, Jorge. “Chinese Aid to Education in Mozambique.” IESE Conference Paper, no. 24 (2012).

Procopio, Maddalena. “The Effectiveness of Confucius Institutes as a Tool of China’s Soft Power in South Africa.” African East-Asian Affairs 2 (2015): 98–125.

Rabine, Leslie W. The Global Circulation of African Fashion. Oxford: Berg, 2002.

———. “Creating Beauty across Borders: Hand-Dyed Textile Arts in Francophone West Africa.” In Mode in Afrika, 97-107.

Ross, Robert. “Cross-Continental Cross-Fertilization in Clothing.” European Review 14, no. 1 (2006): 135–47.

Rovine, Victoria L. “A Meditation on Meanings: African Fashions, Global Traditions.” In Mode in Afrika, 128–34.

———. “Viewing Africa through Fashion.” Fashion Theory 13, no. 2 (2015): 133–39.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. London: Routledge & Kegan, 1978.

Shaw, Jacqueline. Fashion Africa: A Visual Overview of Contemporary African Fashion. London: Jacaranda, 2013.

Shim, Doobo. “Hybridity and the Rise of Korean Popular Culture in Asia.” Media, Culture & Society 28, no. 1 (2006): 25-44.

Steele, Valerie, and John S. Major. China Chic: East Meets West. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1999.

Sylvanus, Nina. “Fakes: Crisis in Conceptions of Value in Neoliberal Togo.” Cahiers d’Études Africaines, no. 205 (2012): 237–58.

———. “Chinese Devils, the Global Market, and the Declining Power of Togo’s Nana-Benzes.” African Studies Review 56, no. 01 (2013): 65–80.

———. “Fashionability in Colonial and Postcolonial Togo.” In African Dress: Fashion, Agency, Performance, edited by Karen T. Hansen and D. S. Madison, 30–44. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Sylvanus, Nina, and Linn Axelsson. “Navigating Chinese Textile Networks: Women Traders in Accra and Lome.” In The Rise of China and Africa in India: Challenges, Opportunities and Critical Interventions, edited by Fantu Cheru and Cyril I. Obi, 132–41. London: Zed Books (in Association with the Nordic Africa Institute Uppsala), 2010.

Tarlo, Emma. Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Tella, Oluwaseun. “Wielding Soft Power in Strategic Regions: An Analysis of China’s Power of Attraction in Africa and the Middle East.” Africa Review 8, no. 2 (2016): 133–44.

US Aid. “Mozambique Textile and Apparel Brief.” 2012.

USITC. Sub-Saharan African Textile and Apparel Inputs: Potential for Competitive Production. Washington DC: United States International Trade Commission, 2009.

Valaskivi, Katja. “A Brand New Future? Cool Japan and the Social Imaginary of the Branded Nation.” Japan Forum 25, no. 4 (2013): 485-504.

Vann, Elizabeth F. “The Limits of Authenticity in Vietnamese Consumer Markets.” American Anthropologist 108, no. 2 (2006): 286–96.

Wheeler, Anita. “Cultural Diplomacy, Language Planning, and the Case of the University of Nairobi Confucius Institute.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 49, no. 1 (2014): 49–63.

Xinhua. “Mozambique’s Top University to Launch Chinese Degree Course.”, January 17, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/mozambique-university-launch-chinese-degree-course

Young, Paulette R. “Ghanaian Woman and Dutch Wax Prints: The Counter-Appropriation of the Foreign and the Local Creating a New Visual Voice of Creative Expression.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 51, no. 3 (2016): 305–27.

Zhao, Jianhua. The Chinese Fashion Industry: An Ethnographic Approach. London, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Zheng, Tiantian. “Karaoke Bar Hostesses and Japan-Korea Wave in Postsocialist China: Fashion, Cosmopolitanism and Globalization.” City & Society 23, no. 1 (2011): 42–65.

Zhou, Ying, and Sabrina Luk. “Establishing Confucius Institutes: A Tool for Promoting China’s Soft Power?” Journal of Contemporary China 25, no. 100 (2016): 628–42.

Endnotes

1 All names are pseudonyms.

2 Jorge Njal, “Chinese Aid to Education in Mozambique,” IESE Conference Paper, no. 24 (2012).

3 Sérgio Chichava, “Mozambique and China: from Politics to Business?” IESE Discussion Paper, no. 5 (2008).

4 Njal, “Chinese Aid to Education.”

5 Sérgio Chichava, Jimena Duran, Lídia Cabral, Alex Shankland, Lila Buckley, Lixia Tang, and Yue Zhang, “Chinese and Brazilian Cooperation with African Agriculture: The Case of Mozambique,” CBAA Working Paper, 2013.

6 Global Times, “China, Mozambique Establish Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership,” May 18, 2016, accessed November 22, 2016, http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/983835.shtml.

7 Chris Alden and Sérgio Chichava, eds., China and Mozambique: From Comrades to Capitalists (Auckland Park, South Africa: Jacana Media, 2014).

8 According to the following source, there were 10,000 Chinese nationals living in Mozambique in 2009: Joao Feijo, “Mozambican Perspectives on the Chinese Presence: A Comparative Analysis of Discourses by Government, Labour and Blogs,” in China and Mozambique, 146–87. The current numbers are unknown but in 2017, members of the Chinese Association in Maputo put the number of Chinese at 40,000, which seems realistic given the steady (official as well as unofficial) influx of Chinese migrants since the early 2000s.

9 Sérgio Chichava and Jimena Duran, “Migrants or Sojourners? The Chinese Community in Maputo,” in China and Mozambique, 188–98.

10 Howard W. French, China’s Second Continent: How a Million Migrants are Building a New Empire in Africa (New York: Knopf, 2014).

11 Paulo Figueiredo, “Mozambique and China: A Fast Friendship into the Future,” Macauhub, August 19, 2016, accessed October 20, 2016, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/mozambique-university-launch-chinese-degree-course.

12 Sérgio Chichava, Lara Cortes, and Aslak Orre, “The Coverage of China in the Mozambican Press: Implications for Chinese Soft Power,” paper presented at the conference China and Africa Media, Communications and Public Diplomacy, Chr. Michelsen Institute, Beijing, 10-11 September, 2014.

13 Xinhua, “Mozambique’s Top University to Launch Chinese Degree Course,” January 17, 2016, accessed November 10, 2016. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/mozambique-university-launch-chinese-degree-course

14 Lucy J. Corkin, “China’s Rising Soft Power: The Role of Rhetoric in Constructing China-Africa Relations,” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 57, special edition (2014): 49–72.

15 Łukasz Fijałkowski, “China’s ‘Soft Power’ in Africa?” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 29, no. 2 (2011): 223–32.

16 Kenneth King, China’s Aid & Soft Power in Africa: The Case of Education & Training (Woodbridge: Currey, 2013).

17 Fijałkowski, “China’s ‘Soft Power’ in Africa?” 223–32; Joshua Kurlantzick, Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power is Transforming the World (New Haven, Conn.: Yale Univ. Press, 2007).

18 Chichava, Cortes, and Orre, “The Coverage of China in the Mozambican Press.”