Volume XIII, No. 2: Fall/Winter 2015-16

The Grapes of Happiness: Selling Sun-Maid Raisins to the Chinese in the 1920s-1930s

REFERENCES | AUTHOR BIO | ![]() Download this article as a PDF file

Download this article as a PDF file

When citing this article, please refer to the PDF which includes page numbers.

Abstract: This paper is a connective case study of Sun-Maid Raisins commercial strategies in the United States and China during the interwar years. It explores in three steps how the California-based company used advertising to bridge Chinese and American consumer cultures, less by reducing the gap than by adapting to Chinese consuming habits and purchasing power. After differentiating the universal/peculiar characteristics of consumers and raisins market conditions in the United States and China, we will examine how the specific organization of Sun-Maid in Republican China proved successful. Like British-American Tobacco and other global companies, Sun-Maid relied on its own distribution system, combining raisin imports and locally-made advertising. Last but not least, a close reading of a Sun-Maid advertisement published in 1928 in the Shenbao (one of the most important newspapers in Shanghai) will serve as a starting point to probe into Chinese and American commercial images. Using historical lenses to analyze their main visual and textual elements, we will discuss how Chinese advertisements merged local/global features of visual culture to invent their own versions of the "sex/women appeal" and the "health appeal", which both enjoyed a worldwide popularity at the time.

Keywords: Children, China, foodstuff, gender, global/local, health, press advertisement, Sun-Maid Raisins, visual culture.

Prologue

In China yesterday some tiny tot became the possessor of a cash, just a fraction of our penny, and he spent it yesterday as thousands of Chinese children did – for eight Sun-Maid raisins in an envelope.1

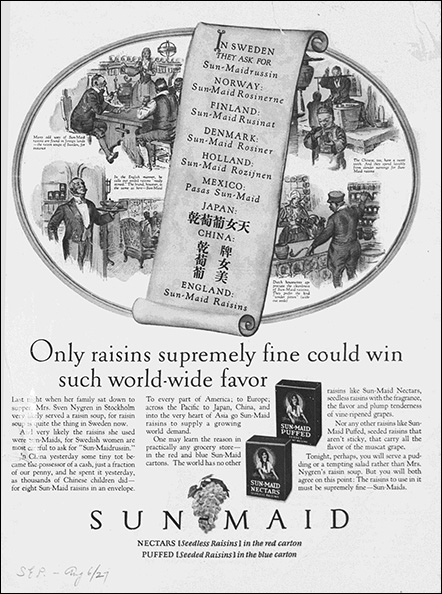

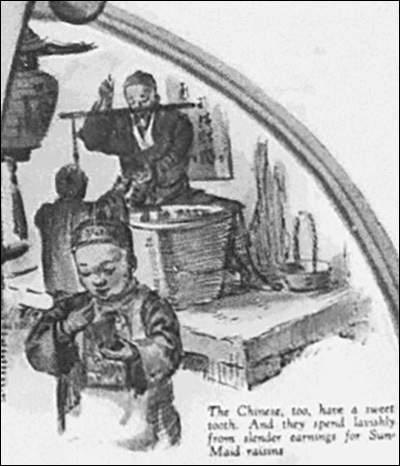

These lines are not quoted from a fairy tale, nor from a guidebook for tourists in China. Unexpectedly, they come from an advertisement for Sun-Maid Raisins published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1927 (see figures 1 and 2). This narrative-style advertisement addressed to Western consumers aimed to narrate the mythical origins of raisins in China. Capitalizing on the powerful attraction of the East in Western countries since the 18th century, it was also designed to romanticize the global success story of Sun-Maid Raisins throughout the world, especially in China. This commercial story offers a perfect prologue for this paper, ideally bringing together the three main strands of the argument.

Figure 1. “Only Raisins supremely fine could win such world-wide favor.” Advertisement for Sun-Maid Raisins, Saturday Evening Post, August 6, 1927. Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. 35mm Microfilm Proofs, 1906-1960 and undated. Reel 36.

Figure 2. Detail drawn from “Only Raisins supremely fine could win such world-wide favor.” Advertisement for Sun-Maid Raisins, Saturday Evening Post, August 6, 1927. Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. 35mm Microfilm Proofs, 1906-1960 and undated. Reel 36.

The first strand draws case studies from among the American global companies active in China since the beginning of the twentieth century to observe the actual “manufacturing” of commercial representations and practices, their circulation throughout the world and their local appropriations by various consumers as in China, which eventually gave birth to a global consumer culture. Why examine Sun-Maid Raisin in particular? Of the many American companies that tried to penetrate the Chinese market in the 1920s, Sun-Maid proved to be one of the most successful. The California Associated Raisin Company launched the Sun-Maid brand in California in 1915, rapidly expanding throughout the world soon after.2

Sun-Maid raisins were introduced in China in the early 1920s and immediately became a very popular brand. How do we explain their success, when so many other Western companies failed to seduce Chinese consumers? What kind of marketing strategies did the company develop to adapt to this specific market? Did they simply export the marketing techniques invented in the United States or did they adapt to the local conditions and Chinese culture? How did Sun-Maid’s efforts figure into the emergence of a transcultural consumer culture in China, especially in Shanghai?

Why examine modern Shanghai in particular? As a major commercial hub, a foreign-dominated and multicultural city, Shanghai presents an appropriate ground for this case study. From the Opium Wars in the mid-nineteenth century until the Republican period (1912-49), various communities (mostly Chinese, American, British, Japanese and French) interacted and intermingled in Shanghai. The city became a fertile laboratory for inventing hybrid representations and practices in the economic and cultural fields. Although China had never been colonized by a Western power, Shanghai harbored colonial regimes in the form of the International and French Settlements. The juxtaposition of these two distinctly foreign entities in Chinese territory makes Shanghai relevant to the making of transcultural discourses and experiences, and their appropriation by the Chinese population.

The second strand argues for the elevation of advertisements and visual sources in general to valuable sources for documenting the history of modern societies – especially Republican Shanghai. As the most widely consumed and circulated images in Shanghai’s visual culture, advertisements are a rich set of source materials for discussions of major historical issues, such as modern/urban life, women and gender, family and childhood, health and the body, consumption and business history, nationalism/imperialism. What did (commercial) images communicate to their viewers? To what extent and under what conditions can historians make efficient use of such sources? Which tools and methodology can they develop to capitalize on their potentials and counteract their limitations? The ambition of this research is to go beyond the surface of images, in order to reveal the making of commercial discourse. For that purpose, there is no alternative but to delve into the archives of the companies that designed advertisements and actively participated in their “engineering” process – not only the business materials produced by companies (here, the Sun-Maid Raisin Company), but also those emanating from advertising agencies (the Carl Crow, Inc. company in Shanghai or the J. Walter Thompson Company in America), other companies, institutions (Shanghai Municipal Council, French Administration), or individual actors (Carl Crow, the American commercial attaché Julean Arnold) who worked in connection with Sun-Maid Raisin.

The third and last strand focuses on the concepts of children and childhood to rethink broader social and major historical debates in recent scholarship. In tandem with the increasing importance of childhood and youth in modern societies, both in the Western and non-Western worlds, children became ubiquitous in consumer culture in the 1920s. As such, they offer ideal lenses for a connective approach to commercial visual culture in Republican Shanghai. What representations and experiences of childhood percolated through Sun-Maid Raisin advertisements? What social roles did Sun-Maid and other American companies assign to American and Chinese children? What visions and practices of health/hygiene, imperialism/nationalism, women/gender were coded within the images of children?

After analyzing the universal/particular aspects of consumers and raisins market conditions in the United States and China, this paper will also examine the specific organization of Sun-Maid in Republican China in order to better understand how and why it proved so successful. A close reading of a Sun-Maid advertisement published in 1928 in the Chinese newspaper Shenbao3 will serve as a starting point to probe into Chinese and American commercial images. Using historical lenses to analyze and model their main visual and textual elements, the last section will examine how Chinese advertisements merged the local/global features of visual culture to invent their own versions of the “sex/women appeal” and the “health appeal” that gained worldwide popularity at the time.

1. Global/local aspects of raisins consumption in Republican China

Western advertisers and advertising professionals who operated in Shanghai in the 1920s-1930s expressed much empathy towards the Chinese people. Shanghai advertising executive Carl Crow4 for instance, posited that Americans and Chinese shared much more in common – in terms of food, clothing, and to a certain extent, customs and mental habits – than did Chinese and other Asian cultures. He further believed that the differences were mostly in details – for instance, in the color of the cloth, not the texture, the design of the jewel, not the materials.5 To discuss the gap between Chinese and American consumers at the time, three salient features will be examined: socio-economical conditions and market opportunities, cultural practices, and visual literacy.

Socio-economical conditions and raisins market opportunities

While raisins were considered to be commonly available foodstuffs by Americans, they were viewed as luxury goods in Shanghai because of the comparatively low purchasing power of the Chinese consumer. Were raisins absolutely unknown to the average Chinese in the 1920s? Although raisins had been traded in China for about two thousands years, they remained merchandising goods restricted to a tiny part of the population and were not advertised as consumer products until the 1920s:

We did go far towards making the Chinese a nation of raisin eaters. Fifteen years ago raisins were practically unknown in China, but now the little red box which forms the packet of the world’s most famous raisin is a familiar sight on the shop shelves of almost every city. (…) When we promoted the sale of raisins we were not introducing any new food product to the Chinese. Arabian traders brought raisins to China about the time of Christ, and later, grapes were grown and dried in North China. These Chinese raisins were not produced in any quantity and did not become a household article until the California raisin played a part.6

In this brief narrative, Crow credits the Sun-Maid Raisin Company with transforming raisins from merchandising goods into products for mass consumption, thereby popularizing raisins in China. However, such assertions should be taken with caution, as Crow was himself in charge of Sun-Maid’s advertising campaigns in China. However, many other contemporary sources testify to the fact that the Chinese raisin market offered unexpected opportunities at the time. The Sun-Maid Company Far East Division reported that exports to China more than doubled in a single year in the mid-1920s: from 108,165 tons in the first eight months of 1923 to 222,588 tons in the first eight months of 1924.7

In the interwar years (1919-1937), the consumption of Sun-Maid Raisins was not limited to the elites, but also reached the lower classes of Shanghai, and extended to cities throughout China’s interior.8 How do we explain such widespread popularity among Chinese consumers, while raisins remained luxury goods for most of them? First, the Chinese standard of living was not as low as it was generally thought in American and Western business circles at the time:

The principal details of several recent successful merchandising campaigns in China by American advertisers indicate that purchasing power of that vast market is much higher that is generally supposed.9

Not only was the overall level of Chinese purchasing power not as low as expected, advertisers assumed it would greatly increase: As more and more people could afford to buy new commodities, the raisin market would naturally, if not indefinitely, expand.10 Yet in the mind of most Western advertisers, this process of increasing wealth flowed from the “miracle factor” that explained any economic success in China: the numerous and ever-growing Chinese population. Such a powerful demographic trend was supposed to balance the relatively high level of poverty in China at the time:

The fact was recognized that the value of the market was due to its multiplicity of purchasers. Although it was recognized that the purchasing power of the average Chinamen is comparatively low, the Raisin Growers were convinced that an attractive unit of sale, though small, would result in a satisfactory volume.11

According to American journalist C.A. Bacon in 1927, the success of California raisins eventually resulted from the perfect match between raisin supply and local demand: the taste of the Chinese for raisins on the one hand, and the absence of local raisin production in China, on the other.12 However, the improvement of social and economic conditions was not the only reason for such success. New consumption habits, the development of modern entertainment and lifestyles in the modern city also contributed to the raisin craving in Shanghai:

Very few kinds of eating - from packages - can be classed as luxury. But even certain kinds of food luxuries sell well in China. Shark’s fin and birds’ nests of Borneo are imported at great cost. Now China likes recreation and modern improvements quite as well as she likes to eat.13

Cultural Practices of Raisin Consumption

Advertisers capitalized both on traditional Chinese food habits and on new patterns of consumption, derived from the process of urbanization and modernization in China. As for traditions, raisin sellers relied on the global taste for sweet combined with the Chinese special taste for (sweet) meat.14 Regarding new habits of consumption, the Sun-Maid Far Eastern Division reported in its market surveys that since the company’s arrival in China, the Chinese had adopted the custom of serving raisins between courses at their feasts, and that raisins were often used by the Chinese in their celebrated custom of presenting gifts.15 Although there is no evidence that Sun-Maid created special gift boxes for Chinese New Year or any other national/local festivals, the company carefully designed colorful packages for local ordinary and daily consumption (see figure 3, 4).

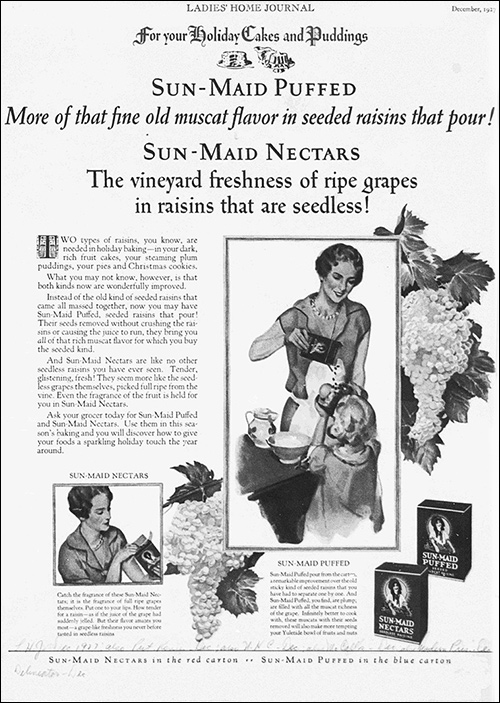

Figure 3. “More of That Fine Old Muscat Flavor in the Seeded Raisin That Pour!” Advertisement for Sun-Maid Puffed and Sun-Maid Nectars. Ladies’ Home Journal. December 1927. Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. 35mm Microfilm Proofs, 1906-1960 and undated. Reel 36.

Figure 4. Advertisement for Sun-Maid Puffed and Sun-Maid Nectars. Ladies’ Home Journal, December 1927 (detail).

While the Chinese consumed plain dried raisins, American consumers preferred more sophisticated products,16 such as raisin breads17 or cakes. In the early twentieth century, cake-baking contests were launched by American advertisers as a new sales method that proved incredibly popular in China as well. Carl Crow employed the cake-baking contest idea to first introduce raisins to the Chinese, offering cash prizes to those who would send the best cakes in which raisins formed a part of the recipe. That marketing strategy proved extremely successful among Chinese consumers, though perhaps not in the sense first intended by advertisers. Crow reported that the day the contest closed, he found his client overwhelmed by more than 500 cakes, forcing them to use rickshaw coolies as tasters in order to select a winner.18

Building consumers’ visual literacy through advertising and packaging

Contemporary advertising agents observed differences in conditions of perception, such as local tastes for colors. Colors are a fascinating issue for historians engaged in the field of visual culture19 and in the most recent scholarship on the history of perceptions and emotions.20 Chinese consumers’ literacy, especially their visual literacy, i.e. their ability to “read” images rather than texts on advertisements, was vividly discussed among professionals at the time. By “visual literacy,” I refer here to a range of visual markers: logotypes, colored packages, or typographical patterns that were used to educate Chinese people to the rising consumer culture. Consumers’ visual habits greatly differed in the United States and China. Crow, who noted the careful attention of the Chinese to details and colors in commercial images, frequently advised his colleagues to integrate these anthropological facts into the process of making advertisements.21 Chinese specific visual habits further led Crow to claim that the ideal Chinese advertisement would be entirely visual – without a word of text.22

Crow was not the only one to call for a “visual turn” in modern advertising. In his report published in 1927, C.A. Bacon presented visual advertisement as the best way to reach Chinese people and the most efficient remedy against consumers’ illiteracy.23

The concern for visibility – the potential visual attraction of advertisement – became ubiquitous in the 1920s, not only in the mediasphere,24 but also and above all in the streets of Shanghai, where the innumerable illiterate consumers would experience various forms of outdoor advertising:

Then again all these and a vast number more can be reached by hoardings or billboards, since signs are intelligible to all who read and to all who cannot read - and the latter make up 90 percent of the population.25

… A proper site had to be selected and the poster itself had to be such as would attract the eye of the Chinese coolie customer… By the same token the art department of an agency must devise pictures for the posters that will attract attention and show the product so plainly that a coolie who cannot read will recognize it in the picture and on the shelf.26

Visual devices included the use of vivid colors, especially the color red, which was and still is very popular in China. Although red had a distinct cultural significance in China and the United States, it nonetheless exemplified positive values in both countries. In the United States, the red color was chosen to match the red sunbonnet worn by the original “Sun-Maid,” model Lorraine Collett, because it was thought to better reflect the color of the sun. However, due to the aforementioned cultural differences, local colors had to be used with much caution. Crow warned against the misuse of colors due to foreign advertisers’ ignorance or misunderstanding of Chinese visual codes and color regimes:

Local color is valuable, but don’t try to use it, unless you are absolutely certain you are right. If you have to depend on an encyclopedia for hints as to local color, better leave it alone, for you are likely to make your advertising ridiculous (recent example in a poster advertising of a well-known American tooth paste featuring an acceptable picture of a Siamese temple in the background and a technically correct elephant in the foreground – but why put a picture of an elephant on a tooth paste advertisement. That doesn’t prove anything except that the picture of an elephant would just as effectively decorate an American advertisement as one designed for the Orient.27

Bacon further reports in 1927 that another major advertising agent, Millington, Limited, also “calls attention to ‘China’s Colour Sense’, showing that modern advertising success is built upon the skillful use of art work.”28

In the 1920s, the Chinese were probably as inexperienced as foreign-born consumers (Black, Latino or European communities) in the United States. This cultural gap among consumers of various nationalities is well described in an investigation on raisin consumption conducted by the U.S. Government in 1926, which reported that the average immigrant in most industrial centers was not accustomed to packaged goods and brand labels.29

According to the same report, although a gradual conversion to the package habit was under way among American consumers, in many cases consumers would still deny that advertising had anything to do with their choice of product purchase, as though susceptibility to advertising were something to be ashamed of.30

Colors were not the only source of trouble for foreign advertising agents in China. Many other representations, such as animals, natural objects or human figures, had to be carefully designed to meet with anthropological habits. Because visual art in advertising required not only technical skills, but also a special knowledge of local culture and conditions of perception, most professionals recommended having the artistic work made by Chinese artists and local agents.31

Advertising agents eventually faced two opposite challenges in China and the United States. In China, the main question surrounding raisin consumption remained: “How to make a luxury product accessible to the average Chinese?” On the other side of the Pacific, American advertisers struggled to render an ordinary food product exceptional to the average Americans by inventing rituals of consumption or rewriting famous fairy tales and myths, such as Cinderella or Robinson Crusoe, in order to endow raisins with magic powers. Therefore, the opportunities offered by the Chinese raisin market made it necessary to carefully plan the advertising campaign. Although the data is absent from Sun-Maid’s own business archives, historians can look to other narrative testimonies to trace the process of making Sun-Maid advertisements. Such reports reveal that Sun-Maid agents in China were well aware that they needed to carefully study the market and adapt their selling methods to conform to the particular demands and customs of the Chinese.32

2. The key to success: imported products and locally made advertising

The Sun-Maid Company imported raisins directly from California, and it relied on its own organization to introduce its goods and to maintain their distribution in China.33

For advertising, we are still uncertain of who was locally in charge of Sun-Maid marketing strategies in Shanghai. There are three possibilities: 1) Sun-Maid’s own in-house advertising department, as for their import and distribution system; 2) The J. Walter Thompson Company, whose London office managed foreign advertising in Europe and Asia;34 3) The Carl Crow, Inc. company – the most likely option. Crow mentions Sun-Maid Raisin in his personal writings several times, in a way that suggests that he was personally in charge of Sun-Maid’s advertising campaigns.6 Furthermore, a 1930 confidential report by the Tokyo Koshinjo, Limited Company explicitly includes Sun-Maid Raisin in the list of Crow’s direct clients.35

Although there is no certainty, it is very likely that the Sun-Maid Raisins company hired Chinese artists or local advertising professionals who were familiar with Chinese culture, as it was recommended at the time. Crow for instance advised that after the advertising had all been planned, the copy written and the illustrations decided on, the most important thing remained to submit the whole plan to the company’s representative in the country where the advertising was to appear.36 He further recommended that the preparation of the advertising copy should only be undertaken by someone who was familiar with Chinese “psychology,” i.e., with the tastes and habits of the Chinese people. He finally warned that advertising campaigns worked up in detail in America were nearly always failures. According to him and other contemporary professionals, the most successful campaigns were those worked out by experienced foreigners residing in China, with the help of trained and educated Chinese.37

3. Adapting Sun-Maid Raisins to Chinese consuming habits

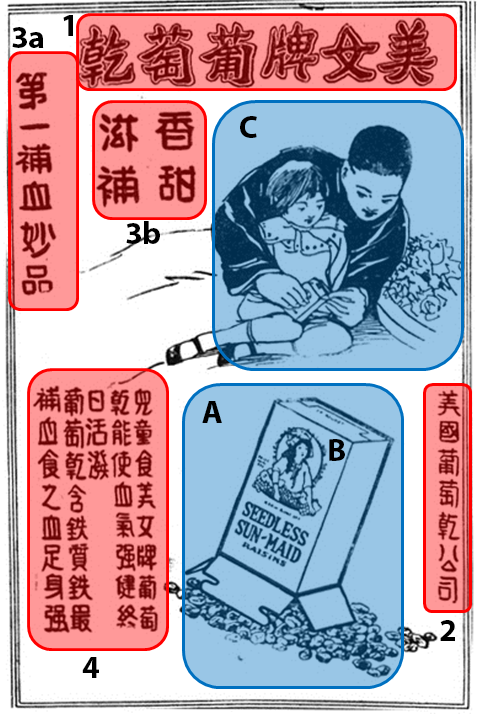

In order to re-embody the general considerations exposed above and to better visualize Sun-Maid advertising strategies, this section proposes to analyze an advertisement published in 1928 in the Shenbao (see figures 5, 6).38 This visual analysis will not only serve as an example of the efforts made by the Sun-Maid company to adapt its products and marketing strategies to the Chinese, but also as a starting point for developing a special methodology for analyzing visual materials from a historical perspective. The advertisements shown in figures 5 & 6 can be broken down into various textual and visual elements. Each one will be closely examined in connection to other parts and to the whole, as well as to other images participating in the emergence of a global-local visual culture in modern Shanghai.

Figure 5. Original Chinese advertisement for Sun-Maid Raisins published in the Shenbao, Shanghai, 1928. Source: http://commonpeople.vcea.net/Image.php?ID=25415.

Figure 6. Analyzing a Chinese advertisement for Sun-Maid Raisins published in the Shenbao, Shanghai, 1928. Source: http://commonpeople.vcea.net/Image.php?ID=25415.

I. Textual elements

Translating the brand name: the challenge of the Chinese language

The brand name (see figure 6: red section 1), strategically placed in the upper right corner of the advertisement should be read from right to left: 美奴牌葡萄幹 (meinüpai putaogan). A close inspection of Sun-Maid’s brand name will serve as a case study to discuss the difficulties that every foreign company faced in China.

In his writings, Crow always warned advertisers on the difficulties that Western companies encountered when translating their brand names into Chinese. Most of the time, advertisers could not satisfy themselves with literal translations and the original brand names had to be completely re- christened, so to speak, to ward off any risk of imitation, confusion or parody:

Every time we take on the advertising of a new brand our first task is to select a suitable Chinese name, and it is not an easy one. But no client ever understands either its importance or its difficulties. In fact we usually have a troublesome time explaining to him that his brand, which is well known in many countries, has to be rechristened in China. The Chinese brand name must be simple, easily read and yet so distinctive that it cannot be easily imitated or confused with other names. When we get a name which meets these requirements we have to make a test for ribaldry. China is the paradise of punsters, and the most sedate phrase may, by a simple change in tone, be turned into a ribald quip which will make the vulgar roar. This is something we have to guard against as we would the plague. We have almost slipped one or twice, but so far have escaped.39

Apart from praising simplicity,40 Crow strongly recommended having the translation done by a native speaker familiar with the local culture, following the same method used for the visual work:

The best advertisements are not translated but written in the native language by someone who has had an opportunity to familiarize himself with the product, and with your advertising policies. But that is not often possible and a clear translation is the next best thing. Better have the translation done in the country in which the advertising is to appear. The work should be, and usually is, done by men who think in the language in which the advertisement is to appear and whose knowledge of English may require some reference to the dictionary.41

While every Western company faced the challenge of translation, some sectors, such as automobiles or games (poker) were more especially concerned, since no words yet existed in the Chinese language to designate such new novelties from the West. According to Crow, it was only through a deep, patient acculturation process to the Chinese language that advertisers managed to overcome these difficulties by combining existing Chinese words or putting old words into new uses.42 For motorcars, advertisers turned to the slang used by the Shanghai chauffeurs and marine engineers, whose complex terminology offered a rich source of inspiration for inventing appropriate words. The translation work eventually resulted in the printing of a glossary containing a wide selection of terms related to automobile that were then integrated in Chinese technical dictionaries.43 To put it another way, translating foreign brand names into Chinese consisted of creating new words rather than choosing terms from pre-existing linguistic repositories. Therefore, advertising actively participated in the broader dynamic of cultural creation, through a complex process of borrowing and hybridizing various glossaries and languages.

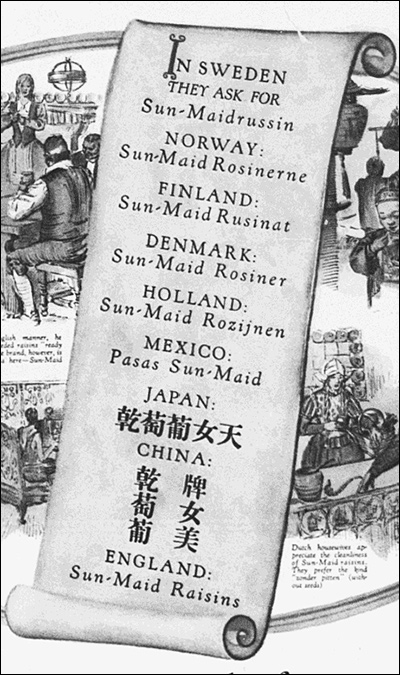

Sun-Maid’s translation problems are perfectly exemplified in one advertisement published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1927 (see figure 1). The image displayed the various names used for Sun-Maid Raisins throughout the world (see figure 7). The original brand name in English was purposely maintained on the package in order to address a multilingual message to Western consumers, thus invited to open their mind to the world and to join Sun-Maid’s efforts to build a global commercial culture. The English letters arising from the page covered with Chinese were designed as visual hooks to attract consumers’ attention as well as teaching aids for helping to identify the original brand and avoid confusion with possible competitors. According to literary historian Shu-mei Shih,44 English letters also served to demonstrate the modern nature of Sun-Maid Raisin. Companies that advertised themselves as modern often printed English words on their packaging, and Sun-Maid may have applied the same strategy. Although in the 1927 Saturday Evening Post advertisement (see figures 1, 8), China is just one among the many markets targeted by the global company, the challenge of translation was even more complicated due to the great variety of dialects in spoken Chinese, and because each province had its ways of pronouncing the Mandarin language:

Even in China the preparation of copy is by no means easy. That which is to appear in all parts of the country needs careful checking by natives of the different Provinces. While the written language is the same all over China, and while three-fifths of the population speak what is known as the Mandarin tongue, yet with the remainder [of] the spoken language and the pronunciation of the written characters vary so greatly that natives of neighboring Provinces, sometimes even of neighboring counties, cannot understand one another.45

Figure 7. Sun-Maid Raisin’s brand name translated into various languages throughout the world. Detail drawn from the Sun-Maid Raisin advertisement “Only Raisins supremely fine could win such world-wide favor,” Saturday Evening Post, August 6, 1927. Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. 35mm Microfilm Proofs, 1906-1960 and undated. Reel 36.

Figure 8. Norman Rockwell, “A Wonderful Bargain Bag.” Advertisement for Sun-Maid Raisin “Market Day Special” bag. 1927. Source: Sun-Maid, 2012: 62-63.

2. Adapting the the company name to consumers’ geographical knowledge

The Chinese name of the company 美奴牌葡萄幹公司 Meinüpai putaogan gongsi, literally “American Raisin Company”) should be read in a top-down direction (see figure 6: red section 2). According to the company’s official narrative, the name “Sun-Maid” was created in 1914 by the American advertising man E.A. Berg. Besides referring to the fact that raisins were made by the California sun, the words suggested the personality of a pretty maid gathering the harvest and making the raisins.46

In contrast to advertisements specifically addressed to the American consumers, the Chinese name of the company skipped California and highlighted instead America. In Chinese advertisements, the West was often called upon as a symbol of modernity and other positive values, such as health, wealth or family happiness. This slight yet important difference reveals the judgment advertising men made in the process of designing their advertisements: while the American audience was supposed to be familiar with the geography of their own country, the Chinese were not expected to have ever heard of California.

3. The slogan: an appeal to health and taste

In China as well as in the United States, the slogans for Sun-Maid Raisins often hybridized appeals to health (補血 buxue, lit. “To enrich the blood”) and appetite (香甜 xiangtian, lit. “Sweet and fragrant”). Crow states that it was easy to convince Chinese consumers that in raisins they could find sugar in its purest and most economical form, and that the iron contained in raisins was actually conducive to health.47 Yet each market had their own specific combinations of these appeals and their distinct marketing histories. While the appetite appeal was strengthened by the “still-life” artistic genre frequently used in American advertisements, the health appeal predominated over the taste appeal in China. The 1928 Shenbao advertisement did not hesitate to recycle the original “iron appeal” invented by Lord & Thomas in 1921:

Early in 1921, Lord & Thomas crystallized the ‘health’ idea they had been featuring in the slogan ‘Had Your Iron Today?’ and almost simultaneously the five-cent package was developed. The ‘iron’ slogan took well, and undoubtedly helped the ‘nickel seller’ along… But there was no continued increase… Iron in raisins provoked universal comment, but like most slogans and health-food pleas produced more talks than sales. People did not seem to be driven to the grocery store over concern for their need of a tonic. Raisins were medicine like sulphur or molasses.48

In the United States, the J. Walter Thompson Company soon abandoned the old “iron appeal” and replaced it with a “modern” appeal more suited to the transformations of American consumer culture, while advertising appeals in China remained focused on health.49

4. The values of raisins: Chinese medicine, body culture and the global obsession for enriching children’s blood

In the 1928 Shenbao advertisement (see figure 6: 3b & 4), the Chinese characters 活泼 (huopo, lively, vivacious) and 身强 (shenqiang, strong body/life) implicitly appealed to Chinese medicine and body culture The advertisement employed the same marketing strategies used for most medical products at the time, such as the famous and worldwide Dr. Williams’ Pills for Pale People. Both Sun-Maid and Dr. William’s advertisements expressed the coexistence of the old and the new by mingling Western science together with Chinese “traditional” physiology and cosmology, in order to facilitate the importation of Western goods and discourses and their acceptance by Chinese consumers.50

On the 1928 Sun-Maid advertisement, local references were then consciously merged with the global obsession for enriching the blood (血氪强 健怒 xuekeqiangjiannu, “To enrich the blood”), which also appeared in many contemporary advertisements in the United States.51

Both Chinese and American societies were more particularly concerned with their children’s blood as an indicator of physical health and, beyond individuals, of the health of the nation. By placing a little girl at the center of the advertising image, the 1928 Shenbao ad may have intended to mirror the general anxiety about the health of youth. For 1920s Chinese consumers especially, the careful attention paid to children may have echoed the concerns of the National government and its social reform projects that aimed to cure the so-called “sick man of Asia,” to strengthen the nation and to resist foreign imperialist powers.52

Sun-Maid Raisin was not the only case of an appeal to children’s health. From August 1926 to March 1927, the Young Companion (Liangyou 良友), one of the most important popular magazines in Republican Shanghai, organized a “Healthy Baby Contest.” Its slogan “Strong babies promise strong people, strong people guarantee a strong nation,” clearly expressed a fervent nationalistic spirit. The sponsorship of the Baohua Company, the company that produced the famous milk brand Momilk (Baohua Powdered Milk), participated in the intermingling of nationalistic concerns and business interests. It further reveals a blurring of political propaganda and commercial discourse that occurred more often than expected in advertising. The Baohua Company established a triangular relationship between milk as a product of mass consumption, health and hygiene as a major social concern in the interwar years, finally linking it with nation building/modernization as the top priority of the National government under Chiang-Kai Shek from 1927 to 1937. Women – as the primary buyers of commercial products and managers of their homes and children as future model citizens – were purposely placed at the center of that complex triangulation.

Such a triangulation was neither restricted to foodstuffs advertising nor to Chinese commercial culture. Because they were supposed to participate in the moral education of citizens-to-be, advertisements for toys53 and handbooks for toys making and using employed the same kinds of arguments.54

II. Visual elements

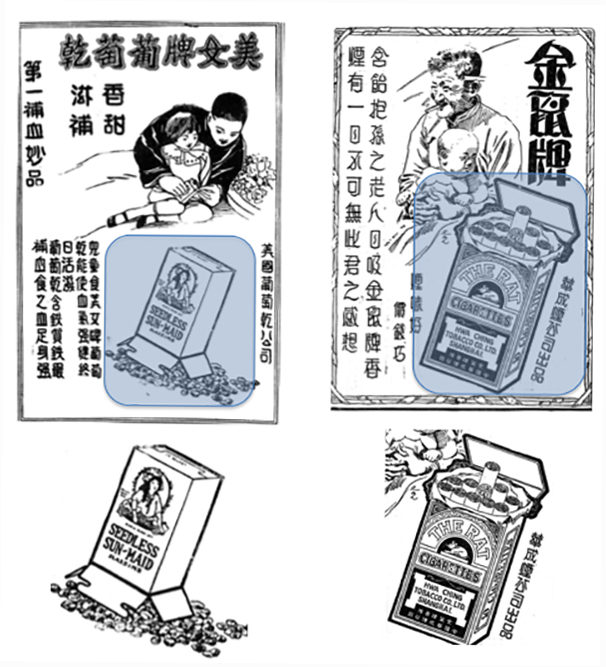

A. Resizing and redesigning the package (see figure 6: blue section A)

In modern China, raisins packages were made smaller and cheaper deliberately to meet the purchasing power of the average Chinese. While each package cost one penny in China and was the same size as a cigarette package, in the United States a package sold for five cents and was as large as a box of breakfast cereal, as depicted on an advertisement for “Sun-Maid Puffed Raisin” published in the Ladies’ Home Journal in 1927 (see figures 3, 4).

One of the first problems to be solved was that of the package. Although it was recognized that the purchasing power of the average Chinamen is comparatively low, the Raisin Growers were convinced that an attractive unit of sale, though small, would result in a satisfactory volume. Obviously, a large number of sales at five or ten cents a package would be impossible, since the coolie could not be expected to spend a day’s wages for food product that he considered a luxury. So the Sun-Maid Raisin Growers reduced their exporting costs to a minimum. They are shipping their product to China in bulk and the raisins are finally retailed in small, attractive, very inexpensive package that are sold for a penny.55

It remains difficult to document the actual weight of packages sold in each country. Based on the contemporary figures provided by Sun-Maid, we may safely presume that the packages in the 1920s-30s offered sizes between 15 to 500 grams.56 At the lowest end of the scale, the Chinese cigarette-style package was probably no heavier than 50 grams. Nevertheless, beyond quantitative data, the most important thing to consider is that packages were carefully adapted to specific market conditions. As the packages were much smaller in China, they were supposed to be lighter and thus more portable, in order to encourage the Chinese habit of eating raisins as snacks, any time and anywhere, even in the street, while going to or from work. The heavier breakfast-size package better fit the domestic uses of raisins in the United States where American housewives used raisins as cooking ingredients for their homemade breads or cakes.57

The closer attention of the Chinese to details makes the graphic work even more sensible/delicate in China compared to the United States, where advertisers/artists would satisfy themselves with rough pictures and sketch-like drawings:

It is very important that the picture of the package or article be correct in every detail. The Oriental may be a romancer and hold truth to be a troublesome personal idiosyncrasy, but he is a stickler for accuracy of details when it comes to merchandise. A great many of the advertising illustrations used in America would not pass a critical test in the Orient because the pictures of the merchandise are too sketchy.58

To have a chance to seduce Chinese consumers, Crow advised that advertisements should observe several rules. First of all, the illustration had to show the package open and the raisins spilling out, to help Chinese consumers to identify the product and the package’s contents:

The illustration should show the package or article and show how it is used. If it is a packaged article it is not enough to show the package itself; the contents must also be depicted, if you wish to avoid any misunderstandings as to what you are advertising.59

That visual device was not restricted to raisins, but extended to every product – such as cigarettes or pills – to meet with Chinese consumers’ general concern for quantity:

The color of the package, the size, and the material of which it is made are of interest and help the consumer to visualize the article. Whatever it is, he will be interested in the quantity.60

Realistic and detailed descriptions further aimed at countering the more general Chinese suspicion towards the advertising profession, which had continuously been associated with charlatans and quack doctors:

After generations of sharp trading with the principle of caveat emptor guiding every transaction, it is not enough to assure him that the package is of generous size. He has been fooled before by generalities like that. He wants to know how many pods, catties, or tubes it contains. If it is a package of pills, how many pills and how you take the pills.61

The practice of representing the package open had not always been used, but resulted from a process of learning/acculturation, in reaction to previous marketing errors. It was primarily designed to avoid confusion with similar products – especially cigarettes:

When Sun-Maid Raisins were first advertised in the Orient, copy was used showing the sealed package as in American advertising. After some months of this advertising it was learned that many thought Sun-Maid was a new brand of cigarettes. Since then all pictures showed the package open and the raisins spilling out.62

The latter point helps to explain the visual similarity between cigarettes and raisins advertisements, which is all the more striking when an advertising sample of each product is juxtaposed side by side (see figure 9). Far from being fortuitous, this resemblance had been observed and theorized by advertising professionals:

In cigarette advertising in China and most other Oriental countries the picture always shows the package open and the ends of the cigarettes protruding so that the customer may count the number of cigarettes in the package. It is very important that the picture of the package or article be correct in every detail.63

Visual mimicry among different products may have derived from several factors. First, the use of mechanical techniques of printing and reproducing images resulted in the recycling of images and visual patterns. Second, there was the collaboration and circulation of artists and other advertising professionals within Shanghai commercial and artistic circles. It was not uncommon for a given artist to design advertisements for various products and brands for several companies. He thus may have reemployed the images or visual patterns used in previous work.

B. The iconic maid as universal logotype: local adaptations of the global woman/sex appeal (see figure 6: blue section B)

The Sun-Maid trademark image, along with its Chinese brand name (美奴牌葡萄 亁 meinüpai putaogan) which directly referred to the logotype, exemplifies the ambiguous significance of female representations in commercial culture and to discuss the wide use of woman/sex appeal to attract consumers.

In contrast with most Sun-Maid advertisements in America and commercial culture in general, the 1928 Shenbao advertisement stands out in two ways. While American advertisements for Sun-Maid usually – if not always – featured women as modern housewives and mothers and major protagonists in family life scenes (see figure 3), and while women were ubiquitous and ostensibly put on display to sell commercial products everywhere in the world,64 in the 1928 Shenbao advertisement the female presence is confined to the iconic maid used as a universal logotype since 1916. How can this difference be explained? Unfortunately and rather intriguingly, no other advertisement for Sun-Maid could be found in the overwhelming Chinese press. There is no way to compare the 1928 Shenbao advertisement with advertising samples for the same brand. However, it is still possible to contrast this discrete female appearance to the usually conspicuous female figures and to locate it in the broader visual culture of China and the United States.

Three main figures of women coexisted and partially overlapped in Republican Shanghai visual culture: the sexy Modern Girl, the enlightened New Woman and the perfect housewife/mother.65 The Modern Girl was usually represented as an attractive pleasure-seeking woman, with distinctive physical attributes, such as bobbed hair and high heels, identifiable by her “sometimes flashy, always fashionable appearance,” her “use of specific commodities and her explicit eroticism,” and her pursuit of romantic love in disregard of the roles of dutiful daughter, wife and mother.66 That Modern Girl was symmetrically opposed to the perfect housewife and mother. As a docile yet smart manager of the house and wise mother of strong children, the latter was presented as the cornerstone of the rejuvenated Chinese nation.67 Last, the New Woman offered a sort of visual compromise between the threatening Modern Girl and the potentially repulsive model of “confined motherhood.” Situated at the crossroads of the Modern Girl and the model housewife, the New Woman presented the most ambivalent figure. On the one hand, she challenged female “traditional” roles and threatened nationalistic projects to build a strong nation through her search for independence, personal achievement, free love and marriage choice. Yet on the other hand, male intellectuals and reformers praised her as a symbol of a progressive nation, as a model citizen, a potentially ideal housewife and mother-to-be of virtuous citizens.

Where should the Sun-Maid representations of women be located in this complex commercial landscape? In the 1928 Shenbao advertisement, the iconic maid used as a logotype presented an ambiguous figure, intermingling the Modern Girl’s sex appeal with a hint of childish ingenuity and the hardworking nature of a female peasant, which recalled the perfect housewife/mother’s wholehearted dedication to domestic work and maternal duties. As the logotype was exactly identical in China and the United States, the same observations also apply to its American incarnations. According to the company’s official history, the trademark was created in 1915 after a real person – Miss Lorraine Collett –was asked by Sun-Maid executive L.R. Payne to pose for a painting, wearing the red sunbonnet which was part of women’s fashion in California at the time.68 The J. Walter Thompson attributed the unchallenged popularity of the iconic female figure in the United States to its ubiquity on packages and other marketing devices. The company further interpreted the consumer enthusiasm as “a tribute to the strategy that has displayed this pictorial character on every box of raisins as well as in every advertisement of the Sun-Maid Growers.”69

Commercial culture in the United States shared many commonalities with the triadic portrait of Chinese women. Recent scholarship has demonstrated that the Modern Girl, the New Woman and the modern housewife/mother were global phenomena, not only in China and America, but in many other metropolises in the world.70 Similar to the Chinese archetypes mentioned above, three main female archetypes of women coexisted in American visual culture and roughly reproduced the same associations with specific products. However, national and local incarnations of the female figures differed according to the sociopolitical and cultural background of the various geographical locations.

Leaving aside Modern Girls and New Women who almost never appeared on Sun-Maid advertisements, differences in Chinese and American representations of housewives/mothers were two-fold. In the United States, advertisers introduced a distinctive female figure, namely the elderly woman or grandmother. They were represented, for instance, in Norman Rockwell painting “A Wonderful Bargain Bag” in 1927 (see figure 8). Did such advertisements reflect the emergence of seniority under way in the interwar years and to the increasing attention that the American society paid to the increasing number of men and women who reached their fifties?71 From a marketing point of view, such advertisements probably expressed Sun-Maid’s concern to target every age and category of people, to encourage transmission of knowledge and practices from mothers to daughters and solidarity through multiple generations.72

While figures of mature and old men often appeared in press advertisements, for instance on one advertisement for the “Rat Cigarettes” in the Xinwenbao in 1933 (see figure 9), old women were comparatively much less visible – if not totally absent from (visual) commercial culture.

Figure 9. Detail from the 1928 Shenbao advertisement (left) and advertisement for “The Rat Cigarettes,” Xinwenbao, 17 September, 1933 (right).

Commercial portraits of Chinese and American housewives further diverged through the slight yet significant variations in the vision of the small modern family, based on the specific triangulation between the individual, the family and the nation developed in each country.73 While Western ideals supported individualism and private life, relatively independent from the state, the Chinese model viewed family as the basic social organization of the state and a kind of microcosm of the nation. In China appeals to emancipation were part of the nationalistic program to strengthen the nation, rather than individualistic projects promoting women’s personal achievement Such subtle differences are betrayed by the tension between images/visual discourses championing an educated manager of a small family and rather conservative slogans/texts encouraging the same to become mothers of numerous children in order to sustain the nation.74 In contrast, on wartime advertisements for the Life Insurance Companies of America which depicts a model family contributing to the national renewal after the war through rebuilding their own house, the personal pronoun “your” used in the slogan “Your personal post-war world” suggests that individual and family achievement are placed before the fate of the nation.

C. An unusual fatherly scene: probing into visual language

In contrast to Sun-Maid advertisements produced for the American market, which systematically depicted housewives and mothers, the 1928 Shenbao advertisement chose to replace the ubiquitous female protagonist by a male figure (probably a father) carefully feeding a little girl Sun-Maid seedless raisins. (See figure 6: c)

In the 1928 Shenbao advertisement, the product and the consumers were equally represented. Though unusual at the time, this picture of a child and her tender father was not an isolated case in the visual culture of Republican Shanghai. A sketch entitled “Past and present China” published in Liangyou magazine in 1932 contrasted in a satirical way an old and a modern couple, the latter operating the reversal of gender roles by placing the baby into his father’s arms, instead of his mother’s. An even more intriguing caricature published in another issue of Liangyou published in 1933 depicted a father at loss after his wife left him with their newborn baby to rear and a messy home to manage. Therefore, we may suppose that actual consumers in 1928 may not have viewed this Sun-Maid advertisement as surprising as we first assumed.

Linking visual discourse with graphic techniques, it should be observed that the black & white drawing may be either a passive response to the medium constraints or an active visual strategy aimed at selling the product. Although the crude materials used for printing newspapers prevented artists from employing various colors and tones and resulted in comparatively less vivid and eye-catching advertisements than those found in magazines, the sketchy appearance of the image eventually conveyed a naive atmosphere which perfectly fit that kind of intimate scene, purposely designed to stir consumers’ emotions:

Advertisers who plan to use the Chinese newspapers should realize the mechanical and other limitations of the publication... It follows that all Chinese papers are crudely printed and that only coarse line drawings can be used. Halftones are out of the question except in the large Shanghai papers.75

Who were the actual consumers of Sun-Maid commercial products and discourses in both China and the United States? Were Chinese women as illiterate as they were said to be?

Although it is almost impossible to identify the actual demographics of the Shenbao’s readers and to know their level of literacy, we may cast doubt on the simplistic view of a gendered readership often assumed by advertising men at the time. According to them, readers could be separated in two main groups: on one side, illiterate women (sometimes joined by workers and the lowest social classes) were viewed as purely “visual readers” of advertisements and commercial discourses; on the other side, educated men from the elite and the middle-classes would have dedicated their reading time to political news and other more “serious” content:

There are even more wives of prosperous men who cannot read, because female education has only recently become a popular fad. The Chinese wife who spends the money in the family cannot read the paper her husband subscribes for, but she will looks at the pictures and, if our advertising shows a good picture of the package with an illustration showing what the article is used for, we feel that it has probably accomplished something, has presented a message to the reader who cannot read.76

In the minds of foreign advertisers and advertising men, the fact that women would be the primary target of commercial products and “visual reader” of advertisements, altogether with their assumed illiteracy, rendered the use of visual devices in advertising all the more necessary:

In no country of the Orient is the rate of literacy very high. It might be argued that those who subscribe for newspapers must be able to read them. Quite right, but the women folks do most of the money spending; as a rule they can’t read but do like to look at the pictures. The illustration should show the package or article and show how it is used. If it is a packaged article it is not enough to show the package itself; the contents must also be depicted, if you wish to avoid any misunderstandings as to what you are advertising.77

However, illiteracy rates in Republican Shanghai were among the lowest in East Asia, and lower than it is generally thought.78 As female education was encouraged by male intellectuals and reformers – in part to produce the smart housewives and mothers called to play an important role in the process of building a strong nation – more and more women actually became educated. By 1936, the number of Chinese attending high schools was six times that of 1912 and modern high schools allowed more individuals, including women, to gain education.79 In Shanghai, the rates of Chinese girls attending schools were particularly high in the 1930s.80 Therefore, we can surmise that Chinese women were not (exclusively) the emotional readers intended by foreign advertisers and suggested by the 1928 Sun-Maid advertisement through its naive drawing of a fatherly scene. While the Sun-Maid Company aimed to reach both sexes and every age and social class in America, modern middle-class housewives certainly remained the primary actual consumers of raisins and the main target of their advertising campaigns.

Epilogue

Through a connective case study of Sun-Maid’s marketing strategies in the United States and China, this paper has shown how the Sun-Maid Raisin Company managed to seduce the Chinese consumers in the 1920-1930s. By relying on their own distribution system, combining raisins imports and locally-made advertising, the company succeeded to convert a luxury product into very popular brand in China. Advertising and merchandising were carefully used to bridge Chinese and American consumer cultures, less by reducing the gap than by adapting to Chinese consuming habits and purchasing power. The company eventually reshaped Chinese visual culture by offering hybrid versions of the “sex/women appeal” and of the “health appeal,” which both enjoyed a worldwide popularity at the time.

This case study of the Sun-Maid Raisin Company contributes to our understanding of the commercial strategies developed by a global company to adapt to the local peculiarities of a distant market like Shanghai. As a single case study, it has no pretention to representativeness. Such method is more valuable when connected to other case studies, related to either competing companies, similar products in different contexts, or different products in the same or similar contexts. This paper has also aimed to show the value of analyzing a visual advertisement with a view to enrich or even revise our knowledge of the company, the historical background and the markets to which it appealed.

Nevertheless, our approach is liable to the following conditions. First, visual analysis shall in turn be enlightened by other historical materials, especially commercial reports, professional handbooks and advertisers’ testimonials. Most cultural approaches tend to consider advertisements as mere representations, systems of signs or «mirrors» of society, restricting them to their semiotic dimensions, ignoring their material features, and confining them to two main media (newspapers or magazines, and calendar posters) and two prominent types of products (medicines and cigarette). In order to deepen cultural studies, we suggest documenting the commercial strategies that laid beneath the surface of images. By scrutinizing the actual making of advertisements, we shall unmask the new breed of advertising men who were responsible for their production. The knowledge of their institutions, and hics, theories and practices in the 1920-1930s, as well as their relationships with other institutions and society as a whole, shall give a fresh life to past images, beyond the usual assumptions on virtual consumers and commercial culture.

Moreover, we shall not satisfy ourselves with a close reading of a single image. To broaden cultural approaches one step further would consist in placing the isolated advertisement within the whole series and campaign in which it was included at the time. Another step would endeavor to graft Sun-Maid advertisements onto the wider network of images within the city of Shanghai: not only the conventional forms of printed advertisements (newspapers, magazines or calendar posters), but also posters and billboards, painted walls and neon lights, street cars and the protean faces of outdoor advertising. Through the careful observation of street photographs and municipal archives, we finally suggest that an effort be made to better understand the ways through which visual culture was not only read or seen, but actually experienced by ordinary Shanghaiese in their everyday lives.

Notes

1 “Only Raisins supremely fine could win such world-wide favor.” Advertisement for Sun-Maid Raisin, Saturday Evening Post, August 6, 1927. Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. 35mm Microfilm Proofs, 1906-1960 and undated. Reel 36.

2 http://www.sunmaid.com/our-history/our-history.html

3 The Shenbao was one of the most important Chinese daily papers in Shanghai. Published from 1872 to 1949, it claimed a circulation of more than 50,000 in the 1920s.

4 Carl Crow (1883-1945) was one of the first advertising men in Shanghai. After studying journalism at the University of Columbia, Missouri, he settled in Shanghai in 1911 where he lived for twenty-five years and founded one the most important American advertising agency at the time, the Carl Crow, Inc. in 1918. He was the author of several best sellers dealing with China during his lifetime. He remains a major source for the history of advertising and consumption in Republican China.

5 Crow, Carl. 1927.”When You Advertise to Orientals.” Printers’ Ink Monthly, December, 39-40, 116-23. Source: Crow, Carl (1883-1945), Papers, 1913-1945. The State Historical Society of Missouri. Manuscript Collections, C41. Scrapbook Series, vol.2 (1916-1937).

6 Crow, 1937: 212-215

7 Despite China’s civil war and Japan’s economic depression resulting in the Japanese luxury tariff, Sun-Maid’s Far Eastern Division did excellent business. The total sales in this Division have reached the fine total of 222,588 cases in the first eight months of 1924 as against 108,165 case in the first eight months of 1923. “Sun-Maid beats August Quota by 3,557 tons – Sales Set New Record for Eighth Consecutive Month.” JWT Newsletter, no.54, November 20, 1924 (p.5). Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. Newsletter Collection, 1910-2005. Box MN6 (1923-1925).

8 “A Smaller Selling Unit Gets Chinese Market for Sun-Maid.” J.W.T. Newsletter, no.47, October 2, 1924 (p.7). Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. Newsletter Collection, 1910-2005. Box MN6 (1923-1925).

9 In order to adapt to those specific social conditions, raisins importers chose to sell small yet attractive units of sale, which by cumulative addition were said to result in satisfactory sales volumes. Source: “A Smaller Selling Unit Gets Chinese Market for Sun-Maid.” Ibid. Crow, 1927: 39.

10 “A Smaller Selling Unit Gets Chinese Market for Sun-Maid.” J.W.T. Newsletter, no. 47, October 2, 1924 (p.7). Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. Newsletter Collection, 1910-2005. Box MN6 (1923-1925).

11 Bacon, 1927: 763.

12 Ibid.

13 Crow, 1937: 214-215.

14 “Since establishing our Oriental offices we have received reports that the Chinese have adopted the custom of serving raisins between courses at their feasts and that raisins are often used by the Chinese in their celebrated custom of presenting gifts.” Chicago Office – Sun-Maid Raisin Gets Record Order from Orient,” J.W.T. Newsletter, no.20, March 27, 1924 (p.3). Source: Record Order from Orient,” that the Chinese have adopted the custom of serving raisins

15 “Your American audience is sophisticated; your Orientals audience is not; and that, to my mind, is the principal reason American copy does not pull as it should in the Orient.” Source: Crow, 1927, p.116.

16 “Bread as a food of universal daily consumption, was the greatest single carrier of raisins to be found and the ultimate objective of the plan was no less than this: to put raisins into the bread of the nation one day out of seven.” Source: “The Story of Sun-Maid.” J.W.T. Newsletter, no.31, June 12, 1924, p.8. J. Walter Thompson Company. Newsletter Collection, 1910-2005. Box MN6 (1923-1925).

17 “When we started promoting the consumption of raisins I suggested that we should conduct a cake-baking contest, offering cash prizes to those who would send the best cakes in which raisins formed a part of the ingredients. It was my first experience with anything of this sort, and it wasn’t until the entries began piling in that I realized how strong the gambling instinct is with the Chinese and how eagerly they will size on opportunity to get something for nothing. The day the contest closed I went to see my client and found him completely surrounded by a sea of cakes (p.212) (...) With these thrown out there were still more than 500 cakes to be judged, and the only sensible way to judge them was by tasting them (...). Under the most favourable of circumstances the merits of a cake cannot be determined with scientific accuracy, and my system worked as well as any other.” (Crow 1937: 214).

18 Henriot 2014; Kuo, 2007, Laing 2004; Pastoureau, 2000.

19 Demartini, Kalifa, 2005; Matt, Stearns 2014. “The Chinese are most discriminating buyers, paying a great deal more attention to all the details of an article than do other peoples.” (Crow, 1926: 192).

20 Crow, 1927: 119.

21 Bacon, 1927: 763-764

22 Des Forges, 2007.

23 Bacon, 1927: 763-764

24 Bacon, 1927: 756-757.

25 Crow, 1927

26 Bacon, 1927: 758.

27 “Government Investigation of Consumer Demand for Raisins,” March 15, 1926 (p.14). Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. Account Files, 1885-2008 and undated, bulk 1920-1995. Box 41.

28 “Government Investigation of Consumer Demand for Raisins,” March 15, 1926 (p.14). Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. Account Files, 1885-2008 and undated, bulk 1920-1995. Box 41.

29 Bacon, 1927: 758-759.

30 Bacon, 1927: 758-759.

31"A Smaller Selling Unit Gets Chinese Market for Sun-Maid.” JWT Newsletter, no. 47, 2 October 1924, p.7. Source : J. Walter Thompson Company. Newsletter Collection, 1910-2005. Box MN6 (1923-1925).

32 “Sun-Maid Raisins Growers Association.” March 15, 1926, p.1. J. Walter Thompson Company. Account Files, 1885-2008 and undated, bulk 1920-1995. Box 41.

33 Report by The Tokyo Koshinjo Limited (Information No. 27340). Shanghai, November 1930. Source: Shanghai Municipal Archives : Q275-1-1840-37 (1934).

34 Crow, 1927: 123.

35 Crow, 1926: 195

36 Established by a British merchant (Ernest Major, 1841-1908) and published from 1872 to 1949, the Shenbao was one of the longest-lived and most successful newspapers in Shanghai, with an estimated audience of 150,000 in 1931 (Mittler, 2004, Tsai, 2010).

37 Crow 1937: 192-193

38 Be sure that your language is simple and avoid the fatal error of cleverness (…). Make the text simple and unequivocal. (Crow, 1927: 116-117).

39 Be sure that your language is simple and avoid the fatal error of cleverness (…).. Make the text simple and unequivocal. (Crow, 1927: 116-117).

40 The translation of the rules of poker was the most difficult job of that sort we ever undertook, but when we began advertising motor-cars, we found plenty of trouble expressing motor-car terms in the Chinese language. Naturally there were no Chinese names for the parts of cars and, in order to define them, it was necessary to define some arbitrary combination of existing Chinese words or to put old words to new uses. This has had to be done with every new article introduced to China, and sometimes it has been very easy. For instance, a mortar is called ‘frog gun’ and an electric light is called ‘bottled moonlight’, two perfectly descriptive phrases. As between ‘bottled moonlight’ and ‘incandescent bulb’ I would choose the ‘bottled moonlight’ as one which at least has created advertising possibilities and would lend itself to romance and to poetic phrases. (Crow, 1937:185-186)

41 Crow, 1937: 185-189

42 Shu-mei Shih, “Shanghai Women of 1939: Visuality and the Limits of Feminine Modernity.” in Jason C. Kuo (ed.), Visual Culture in Shanghai 1950s-1930s, New Academia Publishing, Washington D.C., 2007 (205-240) : 222.

43 Crow, 1926: 195.

44 Sun-Maid Company, op. cit., 2012, p.10.

45 Crow, 1937: 214-215.

46 Lord & Thomas was the first advertising agency to handle the Sun-Maid account before J. Walter Thompson. Source: Sun-Maid Raisins Growers Association, 1926, op. cit. p.1. Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. Account Files, 1885-2008 and undated, bulk 1920-1995. Box 41.

47 J.W.T. Newsletter no.31, June 12, 1924 (p.8). Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. Newsletter Collection, 1910-2005. Box MN6 (1923-1925).

48 Lean, 1995: 76.

49 As it is the case in an advertisement for Foremost Milk made by J. Walter Thompson in 1929. Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. 35mm Microfilm Proofs, 1906-1960 and undated. Reel 9.

50 David Fraser, Smoking out the enemy: the National Goods Movement and the advertising of nationalism in China, 1880-1937, Thesis (Ph. D. in History), University of California, Berkeley, Fall 1999. Gerth, 2003. Glosser 2003.

51 Fernsebner, 2003.

52 In the United States too, advertisements helped the consumers thread health, childhood, family and the nation with one needle: healthy products, such as medicines, vitamins, dairy products or other foodstuffs. For instance, one advertisement for Freihofer’s bread published in the magazine Reading Eagle in 1925, explicitly encouraged children to eat bread in order to strengthen their body and then contribute to the building of a healthy nation (see figure 23). However, anxieties towards children’s health differed in both countries in their respective ways of prioritizing either family or the state (Glosser, 2003). While in China, national interests were placed before family happiness, in the United States family and individual achievement came first. For instance, on a advertisement for Foremost Milk published in 1929-1930 in various women’s and parents’ magazines, depicting a happy mother and her healthy newborn baby, the mother’s emotions are clearly placed at the center of the slogan “Your well-born baby,” through the use of the personal pronoun “your” (see figure 24).

53 “A Smaller Selling Unit Gets Chinese Market for Sun-Maid.” J.W.T. Newsletter, no.47, October 2, 1924 (p.7). Source: J. Walter Thompson Company, Newsletter Collection, 1910-2005. Box MN6 (1923-1925).

54 Sun-Maid Company, 2012: 94.

55 “The Rural Campaign” Sun-Maid Raisins Growers Association, 1926 (p.9). Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. Account Files, 1885-2008 and undated, bulk 1920-1995. Box 41.

56 Crow, 1927: 117

57 Ibid.

58 Crow, 1927: 116.

59 Ibid.

60 Crow, 1927: 117

61 Ibid..

62 Wu, 2012.

63 Ibid.

64 The Modern Girl Around the World Research Group, 2008.

65 Glosser, 2003. Jung, 2013: 179-199. Schneider, 2011.

66 Sun-Maid Company, 2012: 10.

67 The female iconic figure is said to be…a tribute to the strategy that has displayed this pictorial character on every bow of raisins as well as in every advertisement of the Sun-Maid Growers. Government Investigation of Consumer, Demand for Raisins, March 15, 1926 (p.14-15). J. Walter Thompson Company. Account Files, 1885-2008 and undated, bulk 1920-1995. Box 41. For a history of the logotype, see http://www.sunmaid.com/the-sun-maid-girl.html

68 The Modern Girl Around the World Research Group, 2008. Schmid, 2014: 1-16. Schneider, 2011.

69 Laslett, 1989.

70 We questioned every type of ultimate consumer: men, women, and children. Source: Sun-Maid Raisins Growers Association, 1926 (p.11). Source: J. Walter Thompson Company. Account Files, 1885-2008 and undated, bulk 1920-1995. Box 41.

71 Glosser, 2003. Schneider, 2011. Tsai, 2010.

72 Jung, op.cit., 2013: 190

73 Crow, 1926: 197.

74 Crow, 1937: 170-171

75 Crow, 1927: 119.

76 Yan, 2008.

77 Schmidt, 2014: 4.

78 In 1933, Chinese girls represented more than 35% of the children attending school in the Chinese Municipality. Source: 上海市统计补充材料(1934年编), Table 9.

References

Primary Sources

Bacon, C.A. 1927. “Advertising in China.” Chinese Economic Journal and Bulletin: 754-67.

Crow, Carl. 1926. “Advertising and Merchandising.” In China. A Commercial and Industrial Handbook, edited by Julean Herbert Arnold, 191-200. Washington: Government Printing Office.

__________. 1927. “When You Advertise to Orientals.” Printers’ Ink Monthly, December, 39-40, 116-23.

__________. 1937. Four hundred million customers the experiences – some happy, some sad, of an American in China, and what they taught him. New York ; London: Harper & Brothers.

Shanghai Municipal Archives (SMA): Q275-1-1840-37 (1934).

J. Walter Thompson Company. 35mm Microfilm Proofs, 1906-1960 and undated. Reels 35, 36.

J. Walter Thompson Company. Account Files, 1885-2008 and undated, bulk 1920-1995. Box 41.

J. Walter Thompson Company. Newsletter Collection, 1910-2005. Box MN6 (1923-1925).

Common People and the Artists in the 1930s (Advertisement for Sun-Maid Raisins, Shenbao, Shanghai, 1928)

Secondary resources

Büchsel, Ulrike. 2009. “Lifestyles, Gender Roles and Nationalism in the Representation of Women in Cigarette Advertisements from the Republican Period.” (PhD dissertation, Heidelberg University: 2009.)

Cochran, Sherman. 1999a. “Commercial culture in Shanghai, 1900-1945: Imported or invented? Cut short or sustained?” In Inventing Nanjing Road: commercial culture in Shanghai, 1900-1945, 3-18. [New York]: East Asia Program Cornell University.

–––––––––––––––– . 1999b. “Transnational origins of advertising in early 20th-century China.” In Inventing Nanjing Road: Commercial Culture in Shanghai, 1900-1945, 37-58. Ithaca [New York]: East Asia Program, Cornell University.

–––––––––––––––– . 2004. “Marketing Medicine across Enemy Lines. Chinese ‘fixers’ and Shanghai’s Wartime Centrality.” In In the Shadow of the Rising Sun: Shanghai under Japanese Occupation, Cambridge University Press, 66-89.

Demartini, Anne-Emmanuelle, and Dominique Kalifa. 2005. Imaginaire et sensibilités au XIXe siècle: études pour Alain Corbin. Grâne (Drôme): Créaphis.

Des Forges, Alexander Townsend. 2007. Mediasphere Shanghai the Aesthetics of Cultural Production. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10386685.

Fass, Paula S. 2013. The Routledge History of Childhood in the Western World. London; New York: Routledge.

Fernsebner, Susan. 2003. “A People’s Playthings: Toys, Childhood, and Chinese Identity, 1909-1933.” Postcolonial Studies 6 (3): 269-93.

Glosser, Susan L. 2003. Chinese Visions of Family and State, 1915-1953. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Henriot, Christian, and Wen-Hsin Yeh. 2013. Visualising China, 1845-1965: Moving and Still Images in Historical Narratives. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

Jung, Ha Yoon. 2013. “Searching for the ‘Modern Wife’ in Prewar Shanghai and Seoul Magazines.” In Liangyou: Kaleidoscopic Modernity and the Shanghai Global Metropolis, 1926-1945, edited by Paul Pickowicz, Kuiyi Shen, and Yingjin Zhang, 179-99. Leiden: Brill.

Kinney, Anne Behnke. 1995. Chinese Views of Childhood. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&d...

Kuo, Jason. 2007. Visual culture in Shanghai 1850s-1930s. Washington D.C.: New Academia Publishing.

Laing, Ellen Johnston. 2004. Selling Happiness: Calendar Posters and Visual Culture in Early Twentieth-Century Shanghai. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Laslett, Peter. 1989. A Fresh Map of Life: The Emergence of the Third Age. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Lean, Eugenia. 1995. “The Modern Elixir: Medicine as a Consumer Item in the Early Twentieth-Century Chinese Press.” UCLA Historical Journal 15: 65-92.

Matt, Susan J., and Peter N. Stearns. 2014. Doing Emotions History. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Mittler, Barbara. 2004. A newspaper for China? Power, identity, and change in Shanghai’s news media, 1872-1912. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Asia Center; Distributed by Harvard University Press.

Mittler, Barbara, Wen-Hsin Yeh, and Christian Henriot. 2013. “Imagined Communities Divided: Reading Visual Regimes in Shanghai’s Newspaper Advertising (1860s-1910s).” In Visualizing China, 267-377. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

Pastoureau, Michel. 2000. Bleu: histoire d’une couleur. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Patch, Gooseberry. 2012. Sun-Maid Raisins & Dried Fruit. Lanham: Gooseberry Patch. http://public.eblib.com/choice/PublicFullRecord.aspx?p=2001705.

Plum M.C. 2012. “Lost Childhoods in a New China: Child-Citizen-Workers at War, 1937-1945.” European Journal of East Asian Studies 11 (2): 237-58.

Salmon, Christian. 2007. Storytelling: machine à fabriquer des histoires and à formater les esprits. Paris: La Découverte.

Schmid, Carol. 2014. “The ‘New Woman’ Gender Roles and Urban Modernism in Interwar Berlin and Shanghai.”Journal of International Women’s Studies 15 (1): 1-16.

Schneider, Helen M, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, and Department of History. 2011. Keeping the Nation’s House Domestic Management and the Making of Modern China. Vancouver: UBC Press. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459084.

Shih, Shumei. 2007. “Shanghai Women of 1939: Visuality and the Limits of Feminine Modernity.” In Visual culture in Shanghai 1850s-1930s, edited by Jason Kuo, 205-40. Washington D.C.: New Academia Publishing.

Tsai, Weipin. 2010. Reading Shenbao: Nationalism, consumerism and individuality in China 1919-37. Basingstoke [England]; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Weinbaum, Alys Eve, and Modern Girl Around the World Research Group. 2008. The Modern Girl around the World Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10268948.

Wu, Huaiting. 2012. “The marketing of modern women in early twentieth century Shanghai: The creation of consuming modernity and nationalism in advertising.” University of Minnesota.

Yan, Se. 2008. “Real Wages and Wage Inequality in China: 1860-1936.” (PhD diss., University of California at Los Angeles, 2008).

Zhenzhu Wang. 2011. “Popular Magazines and the Making of a Nation: The Healthy Baby Contest Organized by The Young Companion in 1926-27.” Frontiers of History in China 6 (4): 525-37.

Digital Resources

Sun-Maid Official History: http://www.sunmaid.com/our-history/our-history.html

About the Sun-Maid Girl: http://www.sunmaid.com/the-sun-maid-girl.html

Armand, Cécile. 2016a. “Case study no. 10 – Sun-Maid Raisins I (1922-1928) : l’enfance publicitaire par-delà les mers.” Blog post. Last Accessed: February 6, 2016. http://advertisinghistory.hypotheses.org/1967.

______________. 2016b. “Case study no. 10 – Sun-Maid Raisins II (1922-1928) : l’imaginaire de l’enfance détourné.” Blog post. Last Accessed: February 6, 2016. http://advertisinghistory.hypotheses.org/2075.

______________. 2016c. “Case study no. 10 – Sun-Maid Raisins III (1922-1928) : l’enfance publicitaire en Chine.” Blog post. Last Accessed: February 6, 2016. http://advertisinghistory.hypotheses.org/2079.

Biographical statement:

Cécile Armand is currently a PhD student in History at the Lyons Institute for East Asian Studies (I.A.O.) in Lyon, France, under the supervision of Prof. Christian Henriot (Aix-Marseille University) and Prof. Carol Benedict (Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.). Her research project deals with the spaces of advertising in Modern Shanghai in the first half of the twentieth century. She is also involved in Digital Humanities and leads a junior research lab with other doctoral student at the Ecole Normale Superieure of Lyon (ENS-Lyon). She also works as a teaching assistant in the Master’s Degree Program of History and Civilization at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) in Paris.